Author: Thejaswini M A

Translation: Blockchain in Plain Language

Whenever market predictions become controversial, we always circle around one question without directly asking: Can prediction markets really be about "truth"?

Here, we are not referring to accuracy, usefulness, or whether they outperform polls, journalists, or Twitter timelines. We are talking about truth.

Prediction markets price events that have yet to occur. They are not reporting facts; rather, they are assigning probabilities to an open and unpredictably unforeseen future. At some point, we began to view these probabilities as a form of truth.

For most of last year, prediction markets enjoyed their "victory parade of speed." They outperformed polls, beat victory news, and surpassed experts with ailments and PowerPoint presentations. During the 2024 U.S. presidential election, platforms like Polymarket reflected reality better than almost all mainstream prediction tools. This success created a narrative: prediction markets are not only accurate but also rational—they aggregate purer and more honest signals of truth.

Then, a month happened.

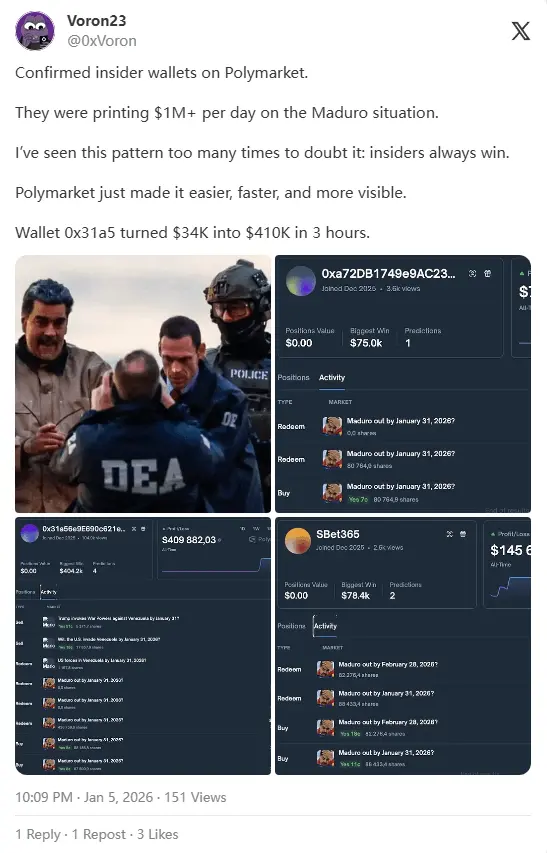

A new account appeared on Polymarket, betting about $30,000 that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro would step down by the end of the month. At that time, the market priced this possibility as extremely low, and it looked like a bad trade.

However, just a few hours later, police arrested Maduro and brought him into New York criminal charges. The account closed with a profit of over $400,000. The market was right. And that is the problem.

There is a comforting story about prediction markets: they aggregate dispersed information, people put their money where their beliefs are, and prices fluctuate as evidence accumulates, converging the crowd towards the truth.

This story assumes a premise: the information entering the market is public, noisy, and probabilistic. For example, tightening poll directions, candidate mistakes, or storm changes. But the "Maduro trade" felt less like inference and more like an accurate timing grasp.

At that moment, prediction markets no longer seemed like clever forecasting tools but transformed into something else: in this place, those with access to channels through analytical reading gained the upper hand.

If the market is accurate because someone possesses information that the rest of the world cannot access, then the market is not discovering truth but monetizing "information that is not cheap." This distinction is more important than the industry is willing to admit.

Accuracy May Be a Dangerous Signal

Supporters of prediction markets often argue: if insider trading occurs, the market will fluctuate earlier, thus helping others. "Insider trading accelerates the truth."

This theory sounds beautiful, but in practice, it collapses due to logical fallacies. If a market becomes accurate because it contains leaked military operations, classified intelligence, or government internal timelines, then it is no longer an information market for any meaningful citizen; it has turned into a secret shadow trading platform.

Rewarding better analysis and rewarding proximity to power are fundamentally different. Blurring this boundary will ultimately attract regulatory attention, not because they are inaccurate, but because they are "too accurate" in the wrong way.

From Margins to Mainstream

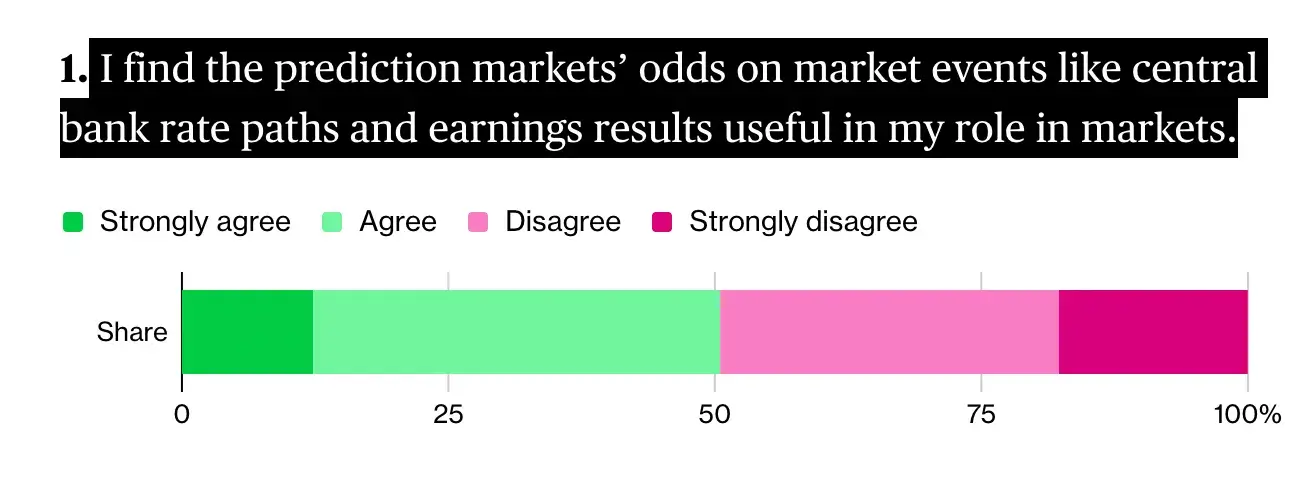

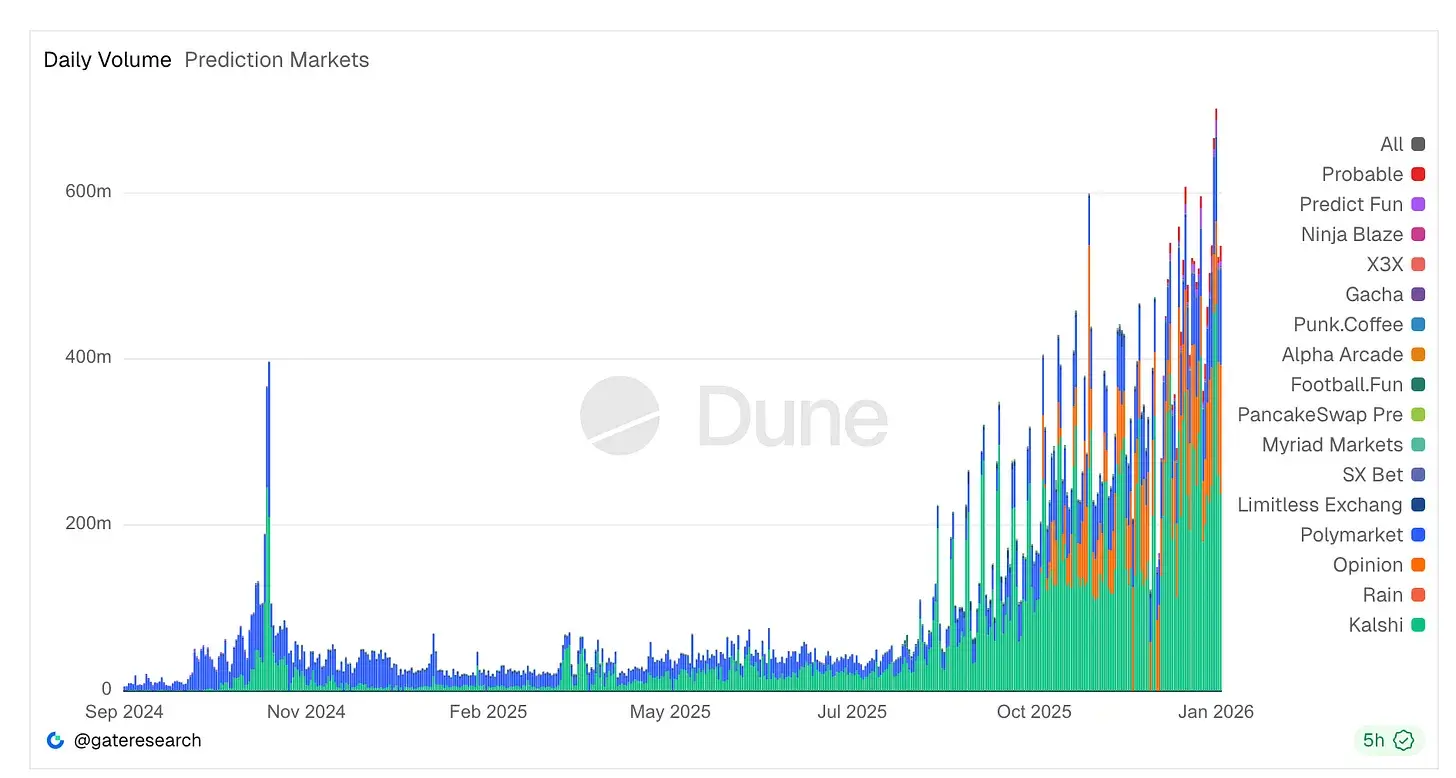

The unsettling aspect of the Maduro incident is not just the payout amount but the backdrop of the explosive growth of prediction markets. Prediction markets have shifted from niche pastimes to an ecosystem that Wall Street is beginning to take seriously.

Surge in trading volume: Platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket have annual trading volumes reaching hundreds of millions of dollars. Kalshi alone processed nearly $24 billion in 2025.

Capital commitment: Shareholders of the New York trading platform have provided Polymarket with strategic deals of up to $2 billion, with the company valued at around $9 billion. This striking Wall Street belief suggests these markets can compete with traditional trading venues.

Regulatory games: Congressman Ritchie Torres and others have proposed legislation aimed at prohibiting government insiders from trading, arguing that these appear more like "front-running" opportunities for uninformed speculation.

"Zelensky Suit": An Overlooked Warning

If the Maduro incident exposed insider issues, then the "Zelensky Suit" market revealed a more core problem.

In 2025, there was a market on Polymarket: Would Ukrainian President Zelensky wear a suit before July? This attracted hundreds of millions in trading volume. It seemed like a joke but evolved into a governance crisis.

When Zelensky appeared in public, he wore a black jacket and trousers designed by a famous designer. The media called it a suit, and fashion experts referred to it as a suit. But the Manhattan machine (Oracle) voted "no."

Because a few large holders of tokens had significant risk exposure on the opposite side of that outcome, they had enough voting power to enforce a settlement result that aligned with their interests. Corruption suggested that the machine's cost was lower than the payout amount.

This is not a failure of the decentralization concept but a failure of the incentive mechanism. The system operated entirely as designed: the degree of profit from human governance depended on how high the cost of lying was. In this case, the profit from lying was higher.

Prediction markets did not discover the truth; they reached a settlement.

It is a mistake to view these events as "growing pains." They are the inevitable result of three combined factors: financial incentives, ambiguous language, and unresolved governance.

Prediction markets did not discover the truth; they reached a "settlement." What matters is not what most people believe but what the system decides counts as an "outcome." This determines a convergence of image, power, and money. When large sums of money are involved, this convergence becomes very crowded.

Shedding the Facade

We have complicated this matter.

Prediction markets are places where people invest in outcomes that have yet to occur. If the event happens as expected, they make money; otherwise, they lose money. All other embellishments are secondary.

It does not become something more sophisticated because the interface is cleaner, the probabilities clearer, it runs on blockchain, or economists are interested. Your reward is not because you have insight but because you bet correctly on "what will happen next."

I see no need to insist that this activity is somehow noble. Calling it "foresight" or "information discovery" does not change the reasons you take risks or bear risks. To some extent, we seem unwilling to admit that people just want to gamble on the future.

In fact, this "facade" is the reason for the difficulties. When platforms tout themselves as "truth machines," every controversy feels like an existential crisis; whereas if we acknowledge this is a high-stakes betting product, then when disputes arise over settlements, it is merely a thorough dispute rather than a philosophical crisis.

Conclusion

I do not oppose market predictions. They are one of the most honest ways to express beliefs under uncertainty. They reveal unsettling signals faster than public polls.

But we should not pretend they are something more convenient than reality. They are not "epistemological engines" but financial tools linked to future events.

Acknowledging this will actually make them stronger. It helps facilitate clearer regulation, more explicit, and more reasonable ethical designs. Once you admit you are operating a betting product, you will no longer be surprised when betting behavior arises.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。