In the short term, I am bullish on risk assets, but in the long term, we must be wary of the structural risks posed by sovereign debt, demographic crises, and the reshaping of geopolitics.

Written by: arndxt_xo

Translated by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

Summary in one sentence: I am bullish on risk assets in the short term due to AI capital expenditure, consumption driven by the wealthy, and still relatively high nominal growth, all of which structurally favor corporate profits.

In simpler terms: When the cost of borrowing decreases, "risk assets" usually perform well.

At the same time, I am deeply skeptical of the narrative we are currently telling about what all this means for the next decade:

The sovereign debt issue cannot be resolved without some combination of inflation, financial repression, or unexpected events.

Fertility rates and demographic structures will invisibly limit real economic growth and quietly amplify political risks.

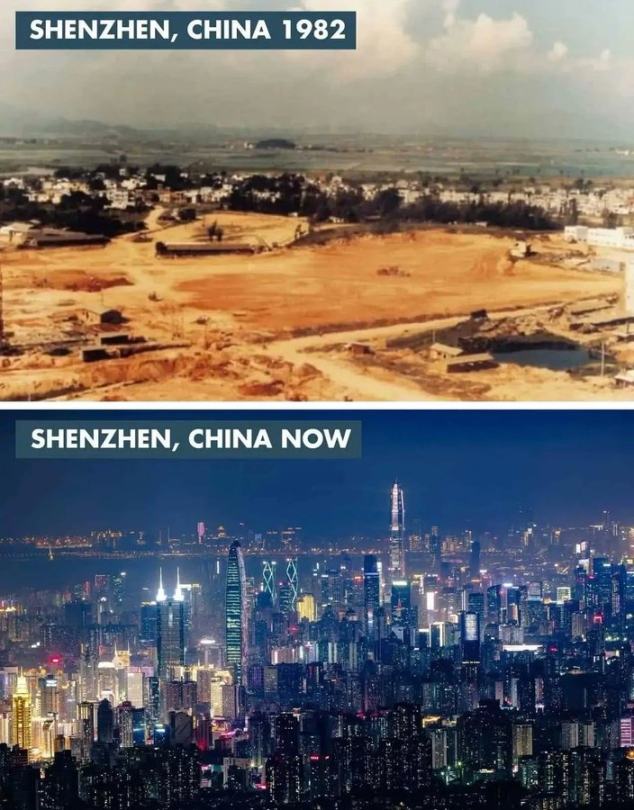

Asia, especially China, will increasingly become the core definers of opportunities and tail risks.

So the trend continues, and we should hold onto those profit engines. However, building a portfolio requires recognizing that the path to currency devaluation and demographic adjustments will be fraught with twists and turns, rather than smooth sailing.

The Illusion of Consensus

If you only read the views of major institutions, you would think we live in the most perfect macro world:

Economic growth is "resilient," inflation is sliding toward targets, AI is a long-term tailwind, and Asia is the new engine of diversification.

HSBC's latest outlook for the first quarter of 2026 is a clear reflection of this consensus: stay in the stock market bull run, overweight technology and communication services, bet on AI winners and Asian markets, lock in investment-grade bond yields, and use alternative and multi-asset strategies to smooth volatility.

I partially agree with this view. But if you stop there, you miss the truly important story.

Beneath the surface, the reality is:

A profit cycle driven by AI capital expenditure, whose intensity far exceeds what people imagine.

A monetary policy transmission mechanism that is partially ineffective due to the massive public debt piling up on private balance sheets.

Some structural time bombs—sovereign debt, collapsing fertility rates, geopolitical restructuring—that are irrelevant to the current quarter but crucial for what "risk assets" will mean a decade from now.

This article is my attempt to reconcile these two worlds: one is the glossy, easily marketable "resilience" story, and the other is the chaotic, complex, path-dependent macro reality.

1. Market Consensus

Let’s start with the general views of institutional investors.

Their logic is simple:

The stock market bull run continues, but volatility increases.

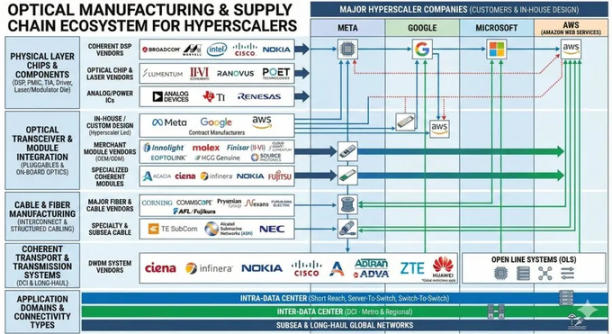

Sector styles need to diversify: overweight technology and communication while allocating to utilities (power demand), industrials, and financials for value and diversification.

Use alternative investments and multi-asset strategies to cope with downturns—such as gold, hedge funds, private credit/equity, infrastructure, and volatility strategies.

Focus on capturing yield opportunities:

As spreads are already narrow, shift funds from high-yield bonds to investment-grade bonds.

Increase exposure to emerging market hard currency corporate bonds and local currency bonds to capture spreads and low correlation with equities.

Utilize infrastructure and volatility strategies as sources of yield to hedge against inflation.

Position Asia as the core of diversification:

Overweight China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.

Focus on themes: the Asian data center boom, leading Chinese innovative companies, enhanced Asian corporate returns through buybacks/dividends/acquisitions, and high-quality Asian credit bonds.

In fixed income, they are clearly bullish on:

Global investment-grade corporate bonds, as they offer higher spreads and the opportunity to lock in yields before policy rates decline.

Overweight emerging market local currency bonds to capture spreads, potential currency gains, and low correlation with stocks.

Slightly underweight global high-yield bonds due to high valuations and individual credit risks.

This is a textbook "late-cycle but not over" allocation: go with the flow, diversify investments, and let Asia, AI, and yield strategies drive your portfolio.

I believe this strategy is broadly correct for the next 6-12 months. But the problem is that most macro analysis stops here, and the real risks begin from this point.

2. Cracks Beneath the Surface

From a macro perspective:

The nominal spending growth in the U.S. is about 4-5%, directly supporting corporate revenues.

But the key question is: who is consuming? Where is the money coming from?

Simply discussing the decline in savings rates ("consumers are out of money") misses the point. If wealthy households tap into savings, increase credit, and realize asset gains, they can continue to consume even if wage growth slows and the job market weakens. The portion of consumption exceeding income is supported by balance sheets (wealth), not income statements (current income).

This means that a significant portion of marginal demand comes from wealthy households with strong balance sheets, rather than broad real income growth.

This is why the data appears so contradictory:

Overall consumption remains strong.

The labor market is gradually weakening, especially in low-end jobs.

Income and wealth inequality is exacerbating, further reinforcing this pattern.

Here, I diverge from the mainstream "resilience" narrative. The macro totals look good because they are increasingly dominated by a small group at the top in terms of income, wealth, and capital acquisition ability.

For the stock market, this is still positive (profits do not care whether income comes from one rich person or ten poor ones). But for social stability, the political environment, and long-term growth, this is a slowly burning hidden danger.

3. The Stimulative Effect of AI Capital Expenditure

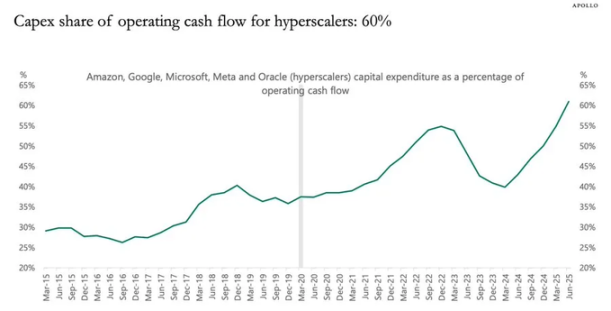

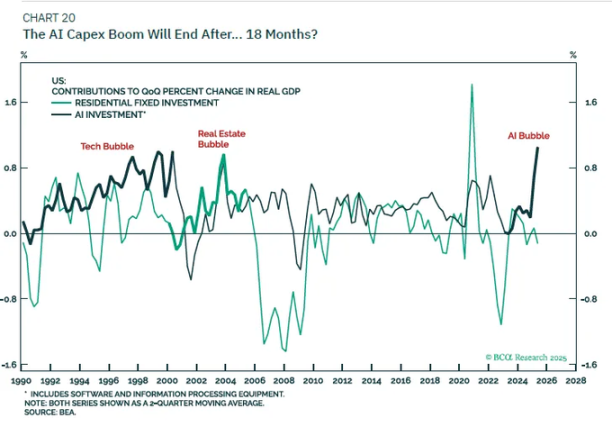

The most underestimated dynamic currently is AI capital expenditure and its impact on profits.

In simple terms:

Investment expenditure is someone else's income today.

Related costs (depreciation) will gradually manifest over the next few years.

Therefore, when AI mega-corporations and related companies significantly increase total investment (for example, by 20%):

Revenues and profits will receive a huge and front-loaded boost.

Depreciation will slowly rise over time, roughly in line with inflation.

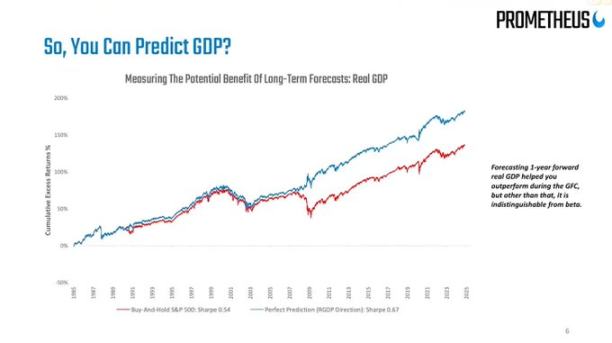

Data shows that the best single indicator for explaining profits at any point in time is total investment minus capital consumption (depreciation).

This leads to a very simple conclusion that differs from the consensus: during the ongoing wave of AI capital expenditure, it has a stimulative effect on the business cycle and can maximize corporate profits.

Do not try to stop this train.

This aligns perfectly with HSBC's overweight on technology stocks and their theme of the "evolving AI ecosystem," as they are essentially also positioning themselves for the same profit logic, albeit expressed differently.

What I am more skeptical about is the narrative regarding its long-term impact:

I do not believe that AI capital expenditure alone can usher us into a new era of 6% real GDP growth.

Once the financing window for corporate free cash flow narrows and balance sheets become saturated, capital expenditure will slow.

As depreciation gradually catches up, this "profit stimulus" effect will fade; we will return to the potential trend of population growth + productivity improvement, which is not high in developed countries.

Therefore, my stance is:

Tactically: As long as total investment data continues to soar, remain optimistic about beneficiaries of AI capital expenditure (chips, data center infrastructure, power grids, niche software, etc.).

Strategically: View this as a cyclical profit boom rather than a permanent reset of trend growth rates.

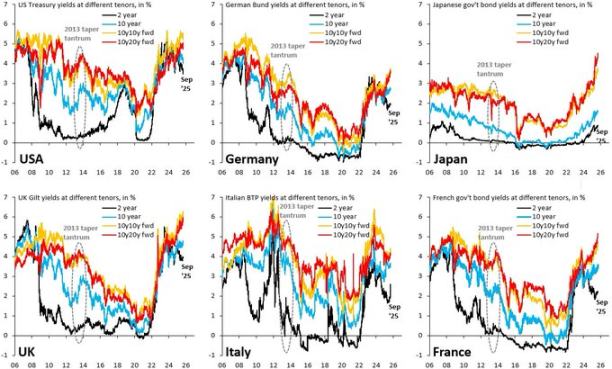

4. Bonds, Liquidity, and the Semi-ineffective Transmission Mechanism

This part becomes somewhat strange.

Historically, a 500 basis point rate hike would severely impact the net interest income of the private sector. But now, trillions of public debt lying on private balance sheets as safe assets has distorted this relationship:

Rising interest rates mean that holders of government bonds and reserves receive higher interest income.

Many businesses and households have fixed-rate debt (especially mortgages).

The end result: the net interest burden on the private sector has not deteriorated as macro forecasts suggested.

Thus, we face:

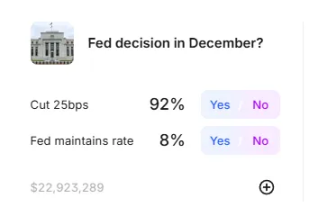

A Federal Reserve that is in a bind: inflation is still above target, while labor data is weakening.

A highly volatile interest rate market: the best trading strategy this year has been mean reversion in bonds—buying after panic selling and selling after rapid rises—because the macro environment has never clarified into a clear trend of "significant rate cuts" or "further rate hikes."

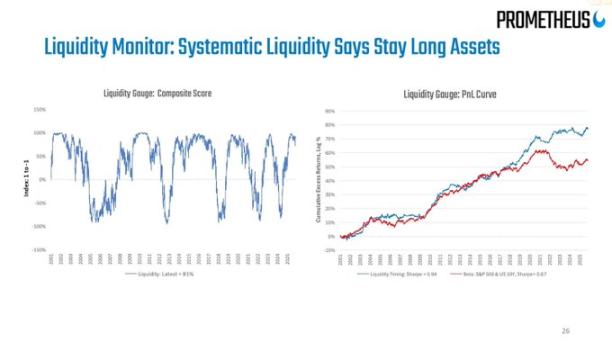

Regarding "liquidity," my view is straightforward:

The Federal Reserve's balance sheet now resembles a narrative tool; its net changes are too slow and too small relative to the entire financial system to serve as effective trading signals.

Real liquidity changes occur in the private sector's balance sheets and the repo market: who is borrowing, who is lending, and at what spreads.

5. Debt, Demographics, and China's Long-term Shadow

Sovereign Debt: The Outcome is Known, the Path is Unknown

The issue of international sovereign debt is the defining macro topic of our time, and everyone knows that the "solution" is simply:

To bring the debt/GDP ratio back to manageable levels through currency devaluation (inflation).

What remains unresolved is the path:

Orderly financial repression:

Maintain nominal growth rates > nominal interest rates,

Tolerate inflation slightly above target,

Gradually erode the real debt burden.

Chaotic crisis events:

Markets panic due to an uncontrolled fiscal trajectory.

Term premiums suddenly spike.

Weaker sovereign nations experience currency crises.

Earlier this year, when the market panicked over fiscal concerns leading to a surge in U.S. long-term Treasury yields, we got a taste of this. HSBC itself pointed out that the narrative around "deteriorating fiscal trajectory" peaked during relevant budget discussions and then faded as the Federal Reserve shifted to concerns about growth.

I believe this play is far from over.

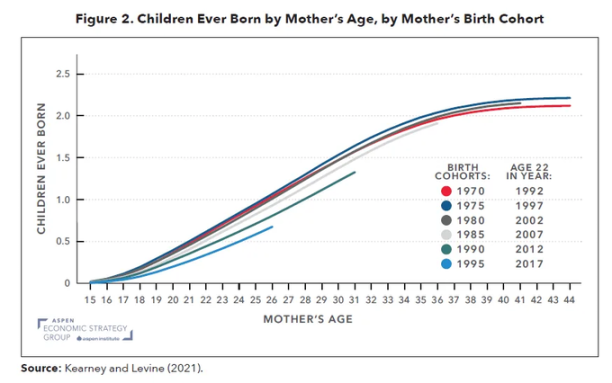

Fertility Rates: A Slow-Motion Macro Crisis

Global fertility rates have fallen below replacement levels, which is not only a problem for Europe and East Asia but is now spreading to Iran, Turkey, and gradually affecting parts of Africa. This is essentially a far-reaching macro shock masked by demographic numbers.

Low fertility rates mean:

Higher dependency ratios (the proportion of people needing support increases).

Lower long-term potential for real economic growth.

Long-term social distribution pressures and political tensions due to capital returns consistently outpacing wage growth.

When you combine AI capital expenditure (a shock of capital deepening) with declining fertility rates (a shock to labor supply),

You get a world where:

Capital owners perform exceptionally well nominally.

Political systems become more unstable.

Monetary policy is caught in a dilemma: needing to support growth while avoiding inflation from a wage-price spiral when labor eventually gains bargaining power.

This will never appear in institutional outlook slides for the next 12 months, but it is absolutely crucial for a 5-15 year asset allocation perspective.

China: The Overlooked Key Variable

HSBC's outlook for Asia is optimistic: they are bullish on policy-driven innovation, AI cloud computing potential, governance reforms, higher corporate returns, low valuations, and the tailwinds from widespread interest rate cuts in the region.

My view is:

From a 5-10 year perspective, the risk of zero allocation to China and North Asia is greater than the risk of making moderate allocations.

From a 1-3 year perspective, the main risks are not macro fundamentals but rather policy and geopolitical issues (sanctions, export controls, capital flow restrictions).

Consider allocating to Chinese AI, semiconductor, and data center infrastructure-related assets, as well as high-dividend, high-quality credit bonds, but you must determine the allocation size based on a clear policy risk budget rather than relying solely on historical Sharpe ratios.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。