Author: FinTax

1. Introduction

In September 2025, the Turkish government proposed a new bill to authorize its Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK) to directly freeze cryptocurrency accounts in its efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. If successfully passed and enacted, this initiative will represent another substantial tightening of Turkey's regulations in the areas of anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT), marking a shift from observation to enforcement in its regulation of the cryptocurrency market. The proposal granting MASAK the power to freeze accounts reflects a shift in regulatory focus—from merely prohibiting payment scenarios to establishing a regulatory system that is monitorable and traceable. Contrary to the proactive and tightening cryptocurrency regulations, Turkey's cryptocurrency market is thriving: despite the clear prohibition of cryptocurrencies as a means of payment, there are no restrictions on individuals or institutions using them for investment and trading purposes; in reality, Turkey ranks among the top countries globally in cryptocurrency usage, with user numbers and trading activity far exceeding those of other emerging market countries. Against the backdrop of currency devaluation and long-term inflation, cryptocurrency assets have gradually become an important choice for the Turkish public in terms of asset preservation and investment.

In this context, understanding Turkey's cryptocurrency tax system and the legal logic behind it has become an important prerequisite for investors and businesses to assess the risks of the local cryptocurrency market. In Turkish law, cryptocurrency assets are defined as non-monetary intangible assets, and their use and trading are jointly regulated by multiple departments, including the Central Bank, the Capital Markets Board (CMB), and MASAK. Although there is currently no independent cryptocurrency tax law, various taxes—including income tax, corporate tax, value-added tax, and stamp duty—are partially applicable to cryptocurrency-related activities from an asset perspective in practice.

Therefore, this article will systematically outline the basic structure and regulatory evolution of Turkey's cryptocurrency tax system, covering legal status, regulatory framework, key tax-related criteria, and collection logic, and further assess its potential impact on businesses and individual investors. In the context of tightening global regulations, studying Turkey's cryptocurrency tax system not only helps to understand the country's regulatory path but also provides actionable risk prevention and compliance references for investors active in emerging markets.

2. Overview of Turkey's Tax System and Regulation

Turkey's tax system is coordinated by the Ministry of Finance, with the Revenue Administration (Gelir İdaresi Başkanlığı, GİB) responsible for tax collection, declaration review, and taxpayer services. The Ministry of Finance formulates the annual fiscal budget, tax rates, and expenditure plans, while the Revenue Administration executes collection and information management functions. The tax year aligns with the calendar year (January 1 to December 31), and a self-declaration system is implemented. Taxpayers must declare their income and tax amounts through the GİB electronic system within the statutory deadline.

2.1 Basic Tax System in Turkey

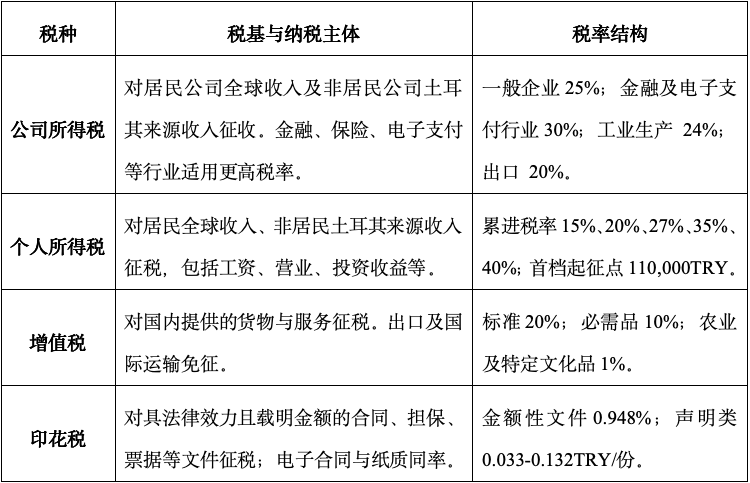

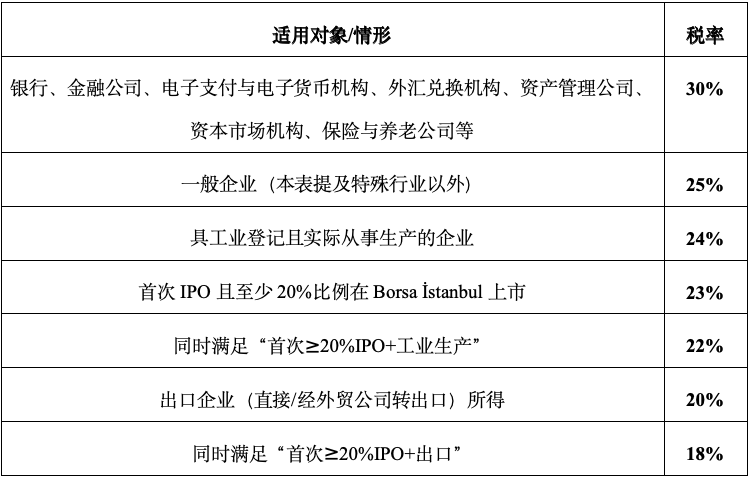

Tax structure: Turkey's overall tax structure consists of direct and indirect taxes—direct taxes include corporate income tax and personal income tax; indirect taxes include value-added tax, special consumption tax, stamp duty, and banking and insurance transaction taxes. Tax revenues are managed uniformly by the Ministry of Finance according to the Public Financial Management Law (Law No. 5018) and are distributed to local governments and social security institutions.

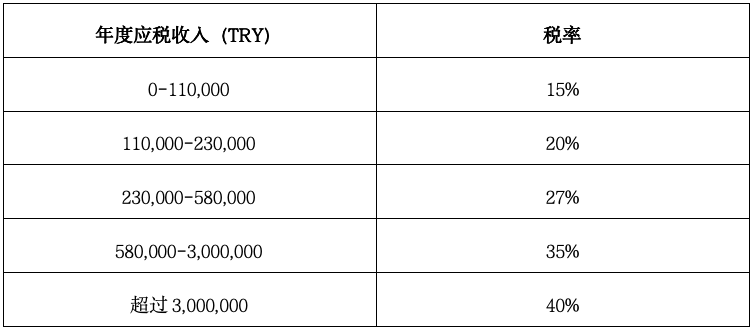

Basic tax rates: According to the GİB 2025 Tax Guide and the revised official gazette No. 32590 (July 2, 2024), Turkey implements a mixed tax system—direct taxes adopt progressive rates, while indirect taxes are at proportional rates. Individuals who have a residence in Turkey or reside for more than six months within a tax year are considered tax residents and are taxed on their global income; other individuals or enterprises are non-resident taxpayers and are taxed only on income sourced from Turkey.

International cooperation: In terms of international cooperation, Turkey has signed double taxation avoidance agreements (DTA) with over 80 countries and follows OECD guidelines to prevent double taxation and profit shifting. All taxpayers must register in the GİB system to obtain a tax number. Individuals can register and file annual declarations through the e-Devlet Portal; businesses must regularly submit value-added tax, withholding tax, and income tax returns through the GİB electronic filing system. Starting in 2023, the Ministry of Finance has fully implemented electronic invoicing, electronic bookkeeping, and electronic stamp tax systems, requiring all registered businesses to generate and store tax documents through electronic platforms.

Digital taxation: Turkey is also actively promoting digital taxation projects. Since 2023, the Ministry of Finance has fully implemented tax digitalization reforms, aiming to achieve complete electronic submission of corporate tax data by 2026. The Ministry participates in the OECD-led Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) system, sharing financial account and cross-border transaction information with international tax authorities to prevent tax evasion and profit shifting.

Overall, Turkey's tax system is characterized by a balance of direct and indirect taxes, centralized collection, and digital filing. The highly centralized structure of the Ministry of Finance and GİB ensures stable fiscal revenue and provides institutional support for future cross-departmental regulation and financial compliance.

2.2 Turkey's Tax Regulatory System

In terms of collection mechanisms, Turkey implements a model that combines quarterly prepayment with subsequent settlement. Corporate income tax taxpayers must prepay taxes quarterly and settle them at the end of the year; personal income tax is levied on a progressive structure based on excess income. Tax audits are conducted jointly by GİB and local tax offices, covering books, bank statements, contracts, and cross-border payment records. If underreporting, omissions, or violations are found, tax authorities can collect back taxes and impose late fees and administrative fines. Tax disputes can be resolved through administrative review or submitted to tax courts.

The Law No. 7524 (Resmî Gazete No. 32550, July 12, 2024) introduced a "domestic minimum corporate tax" and "global minimum tax" system, requiring companies to pay a minimum effective tax rate of 10% on profits, regardless of any incentives they may enjoy, aligning with the OECD Pillar 2 global minimum tax framework. Additionally, the tax exemption policy for free zones has been tightened, continuing to apply only to export income.

Overall, Turkey's tax regulatory system exhibits characteristics of centralized unification, electronic collection, and international cooperation. GİB, as the central tax authority, enhances taxpayer compliance through technological platforms and institutional integration; the Ministry of Finance promotes tax base expansion and multinational tax system coordination at the policy level, marking the entry of Turkey's tax governance into a phase of deep integration of digitalization and globalization.

3. Turkey's Cryptocurrency Tax System and Regulation

3.1 Cryptocurrency Usage

As of now, cryptocurrency usage in Turkey remains highly active. According to Chainalysis's 2025 Global Cryptocurrency Adoption Index, Turkey ranks 14th in the cryptocurrency adoption leaderboard. This indicates that despite tightening regulations, Turkish individuals and institutions continue to use cryptocurrency assets extensively; according to the AInvest market report, it is predicted that by the end of 2025, Turkey's cryptocurrency penetration rate will reach 28.17%, with an estimated total user count approaching 24.82 million. Additionally, the related revenue from the cryptocurrency market is expected to reach $2.2 billion that year.

These figures demonstrate that Turkey's cryptocurrency usage is significant in both breadth and depth of adoption. The Turkish cryptocurrency market is substantial, representing an important market that cannot be overlooked by cryptocurrency investors and practitioners, and it provides motivation for the government to strengthen regulation.

3.2 Legal Positioning of Cryptocurrency

Turkey's legal definition of cryptocurrency assets has undergone a phased evolution from regulatory void to formal legislation.

At the institutional level, the earliest clear regulation came from the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (TCMB) on April 16, 2021, with the issuance of the "Regulation on the Prohibition of the Use of Cryptocurrency in Payments." This regulation was published in Official Gazette No. 31456 and officially came into effect on April 30, 2021. The regulation clearly states two core points: the prohibition of the direct or indirect use of cryptocurrency in any payment transaction; and the prohibition of payment or settlement services based on cryptocurrency provided by payment and electronic money institutions. According to this law, cryptocurrency assets are officially defined in Turkey as "non-monetary assets generated virtually based on distributed ledger or similar technology, distributed through digital networks, but not recognized as legal tender, bookkeeping currency, electronic money, payment instruments, securities, or other capital market instruments." This definition establishes the non-monetary and non-payment instrument attributes of cryptocurrency assets within Turkey's legal system, providing a basis for subsequent enforcement by regulatory authorities.

However, this definition only applies to payment and financial transaction areas and does not automatically extend to tax legislation. The Turkish Revenue Administration has not yet issued any specific announcements or guidelines regarding the taxation of cryptocurrency assets, nor has it clarified the tax attributes of cryptocurrency assets in the current Income Tax Law or Value-Added Tax Law. Therefore, the TCMB's definition of cryptocurrency assets as "non-monetary" does not directly constrain the applicability of tax law; GİB may still classify them as "intangible assets" or "capital gains income" for taxation based on their economic substance in interpretive announcements or collection guidelines.

In other words, within the current legal framework, cryptocurrency assets are neither legal tender nor recognized as an independent tax object; their treatment under tax law will depend on future interpretive announcements from GİB and the Ministry of Finance. If Turkey advances the standardization of cryptocurrency taxation in its tax reform following the EU framework, it is expected to adopt an "economic substance first" interpretive approach, meaning that while retaining the central bank's definition, GİB will distinguish between capital gains and operational income for taxation based on the nature of the income.

3.3 Cryptocurrency Regulatory System

On July 2, 2024, the Turkish Parliament passed amendments to the Capital Markets Law (Law No. 6362)—Law No. 7518, published in Official Gazette No. 32590. The amendment introduced Article 35/B and other provisions, establishing a complete regulatory framework for "Crypto Asset Service Providers (CASPs)"; all CASPs must obtain permission from the Capital Markets Board; they must meet minimum capital requirements, establish internal control and information security systems; their custody and client assets must comply with the principle of independent custody; and foreign unlicensed trading platforms are prohibited from providing services to Turkish residents, otherwise they must cease operations within a specified period.

According to the OECD 2024 "Cryptocurrency Asset Reporting Framework (CARF)" international announcement, Turkey has indicated its intention to participate in the CARF and CRS cross-border tax information exchange mechanisms to achieve international data connectivity for cryptocurrency accounts. This indicates that Turkey's regulatory path is shifting from domestic compliance control to international data collaboration, with future cryptocurrency tax systems being supported by cross-border information transparency.

On the day the amendment took effect, the Capital Markets Board issued a press release further stating that cryptocurrency service providers must complete their licensing applications and compliance filings by March 31, 2025. Additionally, subsequent implementation details published in Official Gazette No. 32509 on March 13, 2025, further specified details on information disclosure, risk warnings, data retention, and cross-border fund transfers. This means that starting in April 2025, unlicensed trading platforms will no longer be allowed to provide services to Turkish residents.

Thus, Turkey's cryptocurrency regulatory structure has begun to take shape: the Central Bank (TCMB) is responsible for defining payment boundaries, the Capital Markets Board (CMB) is responsible for licensing trading and service entities, and the Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK) is responsible for anti-money laundering and account monitoring.

The evolution of the legal system since 2021 shows that Turkey has completed a policy shift from prohibiting payments to licensing operations. The current institutional framework centers on the licensing regulation by the CMB and compliance regulation by MASAK, supplemented by the Central Bank's payment restrictions and legal definitions, forming a comprehensive regulatory system that covers the entire chain of trading, services, compliance, and reporting. This model provides a legal basis for the future extension of tax collection and lays the institutional foundation for Turkey's role in the global governance system of cryptocurrency assets.

4. Taxes and Rate Mechanisms Related to Cryptocurrency Assets in Turkey

Although Turkey has not yet established a specific tax law for cryptocurrency assets, existing general taxes such as corporate income tax, personal income tax, value-added tax, and stamp duty have extensibility in legal logic and applicability conditions. In other words, these existing tax systems may serve as potential channels for cryptocurrency taxation during the government's transitional period in the future. Specifically: corporate tax and personal income tax may correspond to investment income and trading profit from cryptocurrency assets; value-added tax may apply to platform service fees, custody fees, and matching services; stamp duty may be potentially related to legal documents associated with cryptocurrency, such as signed contracts, custody agreements, and guarantee documents.

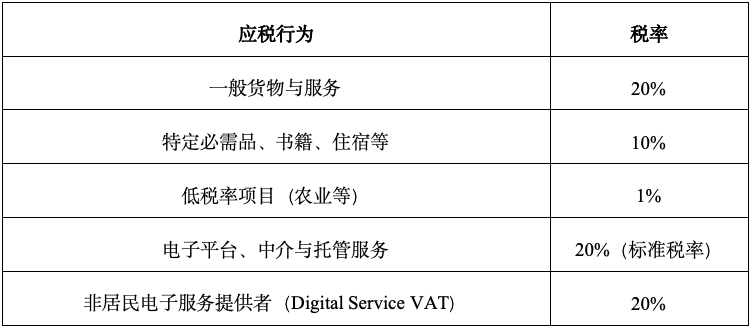

The following table is organized based on original documents from the Turkish Revenue Administration (GİB) and the Official Gazette (Resmî Gazete), displaying the basic applicability scope, tax rates, and official sources of each tax type.

4.1 Corporate Income Tax (Kurumlar Vergisi)

If a business engages in cryptocurrency trading facilitation, custody, payment infrastructure, or market-making activities, its operating income may be considered taxable profit, calculated at the corporate tax rate. If Turkey formally includes virtual asset trading platforms in the CMB licensing system in the future, this tax category will become the core basis for compliance and taxation of cryptocurrency businesses.

4.2 Personal Income Tax (Gelir Vergisi)

If individual investors obtain profit from trading cryptocurrencies, in the absence of specific provisions, such gains may fall under the category of capital gains for personal income tax purposes.

4.3 Value-Added Tax (Katma Değer Vergisi, KDV)

For institutions providing facilitation, custody, consulting, or platform operation services, the service fees and commissions charged may be recognized as taxable services and should be declared at a tax rate of 20%. If detailed rules are introduced, KDV will be an important tax affecting transaction costs.

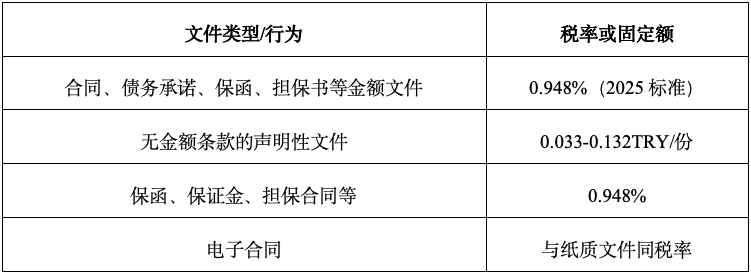

4.4 Stamp Duty (Damga Vergisi)

In scenarios involving OTC trading, custody cooperation, or agency investment agreements, as long as the documents have legal validity and specify amounts, they theoretically need to be taxed according to the stamp duty law.

5. Conclusion

In summary, Turkey's cryptocurrency asset ecosystem exhibits a distinct duality: on one hand, the market is highly active, with strong demand from retail and institutional investors; on the other hand, the regulatory environment is becoming increasingly stringent, with the government continuously promoting compliance and transparency at the institutional level. From Turkey's gradual delegation of authority to MASAK, it is evident that Turkey has transitioned from prohibiting payments to preliminary regulation within the international cryptocurrency regulatory landscape. Tightening regulations do not imply a closed market; rather, they lay the institutional groundwork for a transparent, secure, and long-term cryptocurrency investment environment. What investors need to do is not to evade regulation but to win compliance space through records, documentation, and clear financial logic. This will be the most robust survival strategy for participating in the cryptocurrency market in Turkey in the coming years.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。