Author: CoinW Research Institute Column

This article is the second part of "The 'Midlife Crisis' of Re-staking - Stagnation of TVL, Shrinking Demand, and Transformation Pains (Part 1)."

3. Re-staking Active Verification Service Layer

The Re-staking Active Verification Service Layer refers to the AVS layer, which is designed to allow infrastructures and protocols that do not need to build their own verification networks to share the economic security of underlying staked assets through the re-staking mechanism, thereby reducing the cost of security initiation and enhancing resistance to attacks. Currently, it appears that only a few infrastructure modules that are highly sensitive to security and have the ability to pay continuously truly require Ethereum-level economic security, leading to the development of the AVS layer lagging behind that of the infrastructure layer and yield aggregation layer. Against this backdrop, this report selects the three most prominent AVS in the leading EigenCloud ecosystem within the re-staking track, namely EigenDA, Cyber, and Lagrange, as subjects for analysis.

3.1 Representative Projects of the AVS Service Layer

3.1.1 EigenDA

EigenDA is the first AVS launched by EigenLabs, specifically designed to provide inexpensive and massive storage space for various Rollups. In the blockchain world, data availability (DA) acts like a cloud hard drive for public ledgers, where Rollups need to back up transaction data to this hard drive to ensure that anyone can retrieve and verify the authenticity of transactions at any time. The emergence of EigenDA aims to make this hard drive faster and cheaper while maintaining Ethereum-level security.

Traditional blockchains typically require every node to fully download and store all data, which, while secure, is very congested and expensive. EigenDA adopts a smarter sharding approach, utilizing mathematical principles to break data into many fragments and distribute them to different nodes in the network. Each node only needs to store a small portion of the data, but as long as enough nodes are online, the system can reconstruct the original data like a puzzle. This design allows EigenDA to break free from traditional performance bottlenecks, enabling its throughput to reach Web2-level standards.

Its greatest advantage lies in directly leveraging Ethereum's existing vast credit system. Through EigenCloud, users who have already staked ETH on Ethereum can choose to re-stake these assets to EigenDA's validators. This means that if someone wants to attack EigenDA, they are essentially challenging the security barrier of ETH worth hundreds of billions of dollars. For Rollup developers, this saves the enormous cost of building a secure network themselves, achieving a "move-in ready" level of security.

In terms of commercialization strategy, EigenDA behaves more like a flexible cloud service provider. Traditional Ethereum storage prices fluctuate dramatically with network congestion, while EigenDA allows project parties to reserve bandwidth in advance. Additionally, it is extremely open in terms of payment methods; project parties can pay fees not only with ETH but even with their own issued tokens.

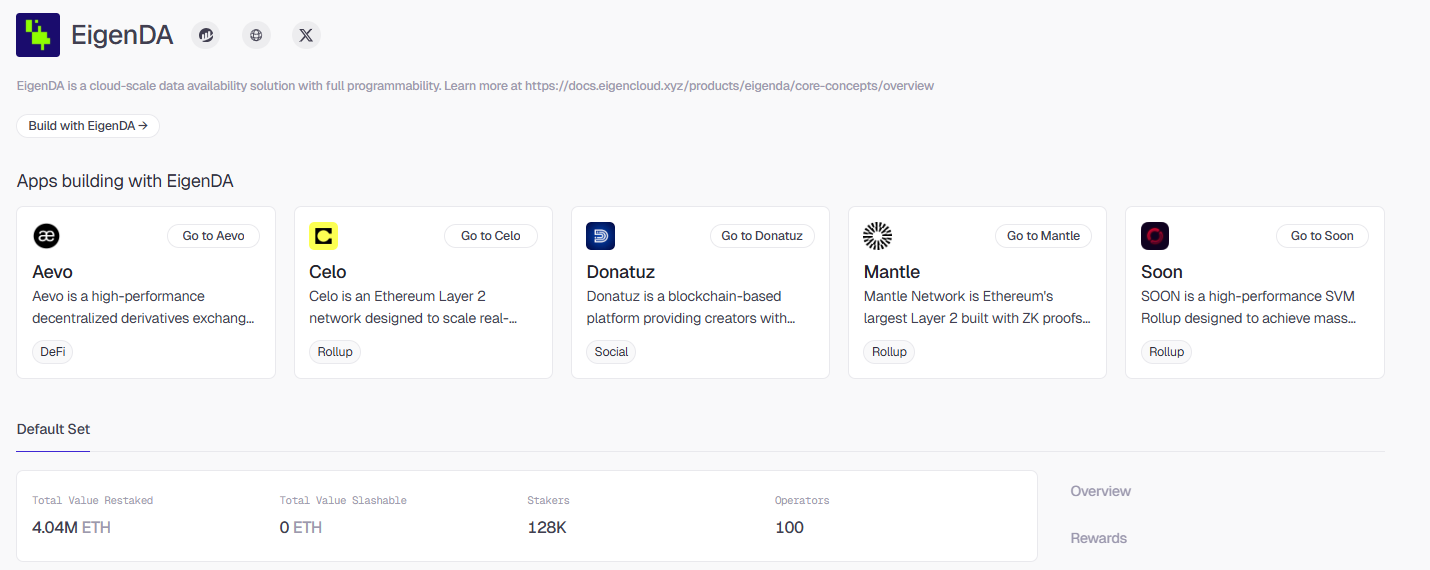

EigenDA is the largest AVS in the entire re-staking ecosystem. As of now, it has locked over 4 million ETH in re-staked assets, attracting more than 120,000 addresses to participate, holding an absolute leading position in both capital depth and network distribution.

However, it must be objectively noted that the current EigenDA is still in the early stages of commercialization. Although it has the largest staked assets on paper among AVS projects, the actual number of penalty cases is zero, indicating that its security constraint mechanism remains more at the institutional planning level and has not yet undergone real large-scale malicious attack tests.

3.1.2 Cyber

Cyber is an application-based AVS that introduces re-staking security through Cyber MACH. Its core logic is to provide additional verification and rapid confirmation capabilities for chain states through MACH AVS while keeping the OP Stack execution layer unchanged, thereby enhancing the interaction experience and security in social and AI scenarios. This model reflects the practical use of AVS at the application layer; it does not replace the existing Rollup security model but serves as an additional security layer that can be accessed on demand.

As of now, its re-staked asset scale is approximately 3.49 million ETH, with about 114,000 participating staking addresses and 45 node operators, placing its security budget in the first tier among application-based AVS. However, at the same time, its punishable assets remain zero, indicating that the relevant punishment and constraint mechanisms have not yet entered a verifiable stage in real-world operations, reflecting a general lag in the implementation of security mechanisms for application-based AVS.

More concerning is that Cyber has clearly slowed down in its project advancement pace. Its official website and white paper content are still at the stage of the first quarter of 2025. This means that although Cyber has absorbed a certain scale of re-staking security on paper, how to convert this security budget into sustainable product capabilities and commercial value remains highly uncertain.

3.1.3 Lagrange

Lagrange is a decentralized computing network aimed at zero-knowledge proof generation, with the core goal of providing high reliability and high availability proof generation services for Rollups, cross-chain protocols, and complex on-chain computing scenarios. Unlike infrastructure-type AVS like EigenDA that directly ensure chain state security, Lagrange addresses a more fundamental issue in computation-intensive scenarios, namely whether proofs can be generated timely, correctly, and continuously.

In the AVS architecture, Lagrange imposes economic security on ZKProver nodes to constrain nodes to complete computing tasks on time and maintain network activity. As of now, Lagrange has absorbed approximately 3.05 million ETH in re-staked assets, with about 141,000 participating staking addresses and 66 node operators.

Lagrange exemplifies the typical use of AVS in the direction of computing services; re-staking security does not directly create demand but provides reliable delivery guarantees for existing demand. It is important to emphasize that the core competitiveness of the ZK Prover network ultimately depends on performance, latency, and unit cost. Re-staking security plays more of a stabilizing role rather than a decisive advantage. Therefore, Lagrange's long-term sustainability still heavily relies on whether ZK applications continue to expand and whether proof services can form a clear and sustainable paid market. This also reflects a common characteristic of computing-type AVS: ample security budgets, but the path to commercialization still requires time for validation.

In summary, the core issue exposed by the AVS layer is not whether re-staking security is strong enough, but whether high-level economic security is "necessarily utilized" in reality. From the latest operational situation, it can be observed that leading AVS have generally absorbed millions of ETH in re-staked assets, but this security supply has not been simultaneously converted into clear and sustainable demand. On one hand, the punishable assets of leading AVS have long remained zero, and security constraints are more at the institutional and expectation levels; on the other hand, whether it is data availability, application-based Rollups, or ZK computing services, their actual payment capabilities and commercial closed loops are still in the early validation stage. This means that the current AVS layer resembles a pre-configuration of security rather than a security demand generated by application pressure.

3. Vulnerabilities and Risk Points of the Re-staking System

1. Risk of Insufficient Shared Security Demand

The core of shared security in re-staking lies in replacing self-built security with paid rental security, thereby reducing the overall cost during the cold start phase. New chains often lack sufficient validator ecosystems and market trust in the early stages, and self-built security needs to bear multiple costs such as inflation incentives, node operation, and security endorsement. During this phase, inheriting the main chain's security through re-staking protocols indeed helps concentrate resources on product and ecosystem development.

However, the premise for this model to hold is that the marginal cost of renting security is significantly lower than the overall cost of self-built security, and that external security can have a verifiable positive impact on user growth or capital retention. As the network enters the mid to late stages, when income, inflation models, and verification systems gradually mature, project parties often have the conditions to internalize security budgets, leading to a decrease in the relative attractiveness of shared security, with demand exhibiting a decreasing characteristic as the project grows.

On the other hand, from the perspective of the overall market structure, the establishment of shared security demand implicitly assumes the continuous emergence of a large number of new chains or new networks in the on-chain ecosystem, i.e., the expansion scenario of "ten thousand chains issuing tokens." However, at the current stage, this situation has clearly weakened, with the number of new public chains and application chains being issued and the scale of financing continuously declining, while development and capital resources accelerate towards a few mature ecosystems. Project parties are more inclined to build applications within existing main chains or Layer 2 systems rather than restarting a new chain that requires comprehensive investment from consensus, security to ecosystem.

Against this backdrop, the demand foundation for providing general shared security to new chains has shrunk. This means that the market demand related to shared security is shrinking and is difficult to form a continuous new demand, with its application scope gradually converging.

2. Risk of Security Dilution Under Financial Leverage

From a mechanism design perspective, re-staking enhances the efficiency of capital utilization by reusing the economic security that has already been deposited in the main chain, allowing the same staked asset to provide verification support for multiple protocols or services simultaneously. Theoretically, this improves capital efficiency. Under the framework of modular architecture and security as a service, this approach is seen as an optimization path that replaces redundant construction with vertical division of labor, helping to lower the threshold for individual protocols to independently bear security costs and enhancing the overall capital efficiency of the system at specific stages.

However, combining the actual operational situations of the infrastructure layer, yield aggregation layer, and AVS layer, it can be observed that this efficiency improvement has gradually developed into implicit leverage amplification in reality. Currently, multiple protocols often share the same batch of collateral assets and validator sets, essentially forming a structure where one pool of funds corresponds to multiple security commitments. As the number of connected protocols continues to increase, the actual attack resistance capability corresponding to each unit of asset is continuously diluted, leading to a decrease in security margins.

At the same time, the punishable assets of leading AVS have long been close to zero, indicating that the staked scale on paper has not effectively transformed into executable economic constraints. In this structure, although the re-staking system nominally enhances capital efficiency, its security guarantees remain more at the expectation level. In the event of extreme situations, the actual defensive capability may be weaker than the security scale reflected on paper, thereby exposing the risk of security being overly leveraged in the pursuit of efficiency.

3. Risk of Highly Concentrated Trust

At the same time, in actual operations, the power of verification nodes in the re-staking system is highly concentrated. This structural imbalance leads to an increasing Matthew effect among validators, where leading nodes gain priority in AVS collaborations due to brand, capital, and historical reputation, further accumulating more income and governance rights, thereby consolidating their monopoly position. The operational stability of some key AVS systems has become highly dependent on a few large validators. Once issues such as downtime, double signing, or collusion occur, it is highly likely to cause a cascading collapse among multiple AVS.

As of now, EigenCloud's market share in the re-staking field still exceeds 60%. This dominant position gives its protocol decision-making influence an exceptionally large impact, forcing many projects to build around EigenCloud, further amplifying its leverage effect on the overall security of the ecosystem. If the platform experiences a smart contract vulnerability, governance attack, or policy change, the chain reaction will be difficult to isolate. Although protocols like Babylon are attempting to enter this market and introduce innovative mechanisms such as Bitcoin staking to weaken centralization, their user base and ecological depth are still far inferior to EigenCloud. This means that the current ecosystem has not yet established an effective multipolar check-and-balance mechanism, and the re-staking system still faces systemic risks triggered by single points of failure at the top.

4. Weakness of the Liquidation Chain and Negative Feedback

The increasing complexity of re-staking protocols is making liquidation risk one of the core challenges facing the entire ecosystem. Different protocols exhibit significant differences in their reduction mechanisms and liquidity designs, making it difficult for the re-staking system to form a universal assessment standard. This structural heterogeneity not only raises the threshold for cross-protocol integration but also weakens the unified response capability of the liquidation market to risks. Currently, there is a lack of an effective cross-protocol risk liquidation mechanism, leaving the entire re-staking system in a potential state of systemic loss of control without a unified credit anchor or risk isolation. Different protocols adopt their own reduction trigger mechanisms, validator distribution logic, and collateral liquidity strategies, leading to the formation of isolated risk structures on-chain, making coordinated governance in cross-protocol scenarios challenging.

5. Liquidity Mismatch and Yield Volatility Risk

Re-staking takes already liquid staking derivatives or native ETH and re-collateralizes them to external services, supporting users in participating in lending, trading, and yield aggregation operations. This seemingly enhances capital efficiency, but the actual exit period of the underlying staked assets remains lagging. For example, EigenCloud's re-staked assets require a mandatory custody period of 14 days before they can be withdrawn. This mismatch between exit periods and liquidity does not manifest as a problem when market sentiment is stable, but once a trust event occurs, it can easily trigger a liquidity run. Re-staking yields do not come from a single source but are driven by multiple factors, including ETH main chain staking yields, AVS incentive distributions, node operation profit sharing, and additional returns from participating in DeFi protocols. This multi-source driven yield structure increases yield rate volatility, making it difficult for investors to assess their true yield-risk ratio and thus make stable holding or allocation decisions.

4. Conclusion

Currently, the re-staking track has shifted from a phase of rapid early growth to one where structural issues are gradually emerging. On one hand, it quickly rose as an extension of Ethereum's staking mechanism, seen as a new way to release on-chain trust capital; on the other hand, the actual operational mechanisms continuously expose issues of centralization and risk accumulation, posing challenges of limited resources and growth bottlenecks for the entire track.

The market demand related to shared security is shrinking and is difficult to form a continuous new demand, with its application scope gradually converging. At the same time, there is also the risk of security dilution under financial leverage. In most mainstream protocols, the concentration of validator delegation continues to rise, with leading nodes almost bearing the entire system's trust weight, and the design of the protocol layer often relies on a single governance structure and highly centralized authority control. This structural flaw not only undermines the original intention of redistributing trust but also, to some extent, forms a new center of concentrated power. Re-staking, as an independent track, is experiencing a periodic retreat, with the market not only losing confidence in a single project but also beginning to question the efficiency of the entire shared security model and the sustainability of its returns.

Due to the persistence of this situation, leading projects are actively exploring diversification of paths. The most representative, EigenCloud, is no longer limited to the positioning of re-staking protocols; its new positioning is attempting to take on a broader decentralized computing resource market and integrate with the X402 track. This transformation indicates that EigenCloud is seeking to establish itself as a more comprehensive infrastructure layer. Meanwhile, projects like Ether.fi are also beginning to expand towards non-staking directions, attempting to penetrate broader use cases such as payments, reflecting the track's adjustment and shift away from a single staking logic.

However, whether it is staking, re-staking, or liquidity re-staking, it is difficult to escape dependence on the underlying asset prices. Once the price of the native token declines, the principal of stakers suffers losses, and the re-staking system, layered on top of multiple structures, will further amplify risk exposure. This risk nesting structure gradually exposed itself after the market boom in 2024, raising doubts about the re-staking model.

From a future potential perspective, the re-staking track is seeking a possible path from high-yield tools to the development of underlying credit protocols amid its growing pains. The effectiveness of this reshaping largely depends on whether it can break through in two directions: internally, the market is observing whether re-staking can achieve deeper integration with stablecoin mechanisms, attempting to construct a foundational infrastructure prototype similar to on-chain benchmark interest rates by outputting standardized underlying security and expected yield rates, thereby providing a low-volatility, liquidity-deep yield anchor for digital assets; externally, re-staking has the potential to become a connection between decentralized ecosystems and traditional financial credit centers. If it can effectively solve the challenges of risk quantification and compliance integration, it may transform Ethereum's consensus security into a credit endorsement understandable by traditional capital, accommodating institutional-level assets like RWA.

Overall, the re-staking track is attempting to break away from a single risk nesting narrative and shift towards a more certain infrastructure role. Although this transformation faces dual challenges of technical complexity and regulatory uncertainty, its systematic reconstruction of the on-chain credit system will still be an important dimension to observe in the next stage of digital asset ecosystem development.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。