Original Title: LONG READ: The untold story of how crypto's hottest derivative came to be

Original Author: IZABELLA KAMINSKA, The Peg

Translation: Peggy, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: Perpetual contracts are often seen as one of the most speculative trading tools in the crypto market, and their inventor and the exchange that nurtured them have long been embroiled in controversy. BitMEX was once the center of global crypto derivatives trading but faced regulatory backlash due to a lack of anti-money laundering compliance; one of its founders, Ben Delo, is both the designer of the perpetual contract and has stood in the dock of the U.S. judicial system. Innovation, expansion, and institutional friction have always intertwined in this case. This article returns to the starting point of the birth of the perpetual contract, tracing how it spontaneously evolved a pricing and clearing mechanism in the absence of central design, starting from BitMEX's engineering choices, market constraints, and serendipitous inspiration.

The original text is as follows:

In September 2015, in the back seat of a taxi in Shanghai, a young mathematician and his co-founder were trying to solve a long-standing problem for their crypto exchange. What they sketched out was a strange futures contract with no expiration date.

This invention became the financial instrument later known as the "perpetual future." Today, it has grown into one of the most important and highest-volume derivatives in the crypto market, yet it remains rarely discussed in traditional financial systems.

In recent weeks, a few observers have finally begun to notice: this tool is impacting the evolution of the modern financial system. However, the discussions remain limited and understated, and more importantly, they overlook a key context—the rise of perpetual contracts is not an isolated event but coincides with three deep structural transformations:

- Central banks returning to a "scarce reserves" operational framework;

- Unsecured financing as a source of emergency liquidity is disappearing;

- The cost of maintaining funds in the international dollar payment system continues to rise.

It is against this backdrop that the rise of stablecoins has created a new, fully collateralized, short-term source of dollar financing. Interestingly, there is no central authority in this system to determine the pricing and clearing of this liquidity at the margin.

Currently, all of this is primarily accomplished through the funding rate of perpetual contracts—this mechanism can operate autonomously as long as stablecoins are being traded.

Even more surprisingly, the official financial system spent years, with multiple regulatory agencies and expert committees repeatedly studying, discussing, and designing, before finally launching a replacement for LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate); yet the funding rate generated by perpetual contracts, which now clears tens of trillions of dollars in stablecoin funds daily, is almost entirely a product of natural evolution.

Meanwhile, an academic debate about the operational framework of monetary policy is continuing to ferment within central banks. Central bank officials are gradually realizing that the old system of relying on unsecured federal funds rates to transmit monetary policy and price marginal liquidity is no longer applicable. The problem is that no one can reach a consensus on "which market interest rates should anchor the new operational framework."

If the historical experience of LIBOR and the Eurodollar market still holds reference value, then the true cost of marginal dollar financing always appears at the intersection of the official and unofficial systems. Since stablecoins are becoming the new "secured Eurodollars," the indicator that most accurately reflects systemic funding pressure is likely the funding rate of perpetual contracts that helps these systems complete their clearing.

However, this view—that perpetual contracts are playing a key role in absorbing, pricing, and alleviating liquidity pressure, while traditional mechanisms struggle to respond gracefully—has yet to truly enter the vision of central bank decision-makers.

For this reason, it is particularly important to look back and examine how these tools were born and what problems they initially sought to solve. The following is this history, from my unique perspective of having continuously tracked this field since the early days of the crypto industry.

The protagonist of the story is Ben Delo: a well-spoken mathematician trained at Oxford University. In 2014, he co-founded the BitMEX exchange in Hong Kong with Arthur Hayes, an outspoken American from Detroit, and Samuel Reed, another American who has made fewer public appearances.

In 2020, the three were indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice for violating the Bank Secrecy Act, as BitMEX failed to implement sufficient anti-money laundering (AML) mechanisms while rapidly growing into one of the largest crypto derivatives trading platforms in the world. In 2025, with Donald Trump unexpectedly issuing a pardon for them, public attention once again turned to these three founders.

But before all these headlines, they were just three entrepreneurs trying to solve the dissatisfaction traders had with the design flaws of crypto futures.

I first intersected with one of them in 2017. At that time, I was still writing for FT Alphaville under the Financial Times, primarily reporting on the latest frenzies in the crypto industry, particularly initial coin offerings (ICOs).

Someone suggested I talk to Arthur Hayes. They described Hayes as an extremely market-savvy industry commentator, and more importantly, he could provide a realistic, pragmatic perspective unencumbered by narrative.

To be honest, I was cautious at the time. The crypto space was filled with hype and scams, and almost everyone was pushing their own agenda. But Hayes did not disappoint me.

Our conversation was unusually calm and direct. He was clearly very aware of how real financial markets operate and was highly immune to the exaggerated narratives and empty talk common in the crypto industry.

When discussing ICOs, he pointedly said, "People are willing to pay for something, but in the end, they own nothing. It's just a promise from a development team, and whether it’s actually useful, no one knows." "Interestingly, people can raise $10 million in a few minutes based on a dream."

At the time, I did not realize that there was a deeper meaning behind these words.

At that time, BitMEX's profits were experiencing a dramatic surge, partly thanks to the "blockchain is everything" ICO narrative. Quirky projects like "Dentacoin" (a token claimed to be used only for dental payments) caused a massive flow of funds within the crypto ecosystem, and BitMEX naturally became a beneficiary of this frenzy.

But for the founders, this glory may have come with a hint of bitterness.

Just a few years prior, they had struggled to attract investor interest in BitMEX.

Ben Delo later told me that from 2014 to 2016, they attempted to raise funds multiple times but repeatedly hit walls. Without external support, they could only rely on their savings to keep the project running, working in cafes and apartments, slowly but surely advancing the product.

It wasn't until September 2015 that a flash of inspiration from Delo completely changed their fate.

While pondering how to make leveraged trading easier for ordinary users, he conceived a derivative structure with no expiration date—the perpetual contract. By 2019, this innovation had propelled BitMEX to become one of the most profitable exchanges in the industry.

It was also during this time, just before BitMEX reached its peak and before the pandemic broke out, that I had another completely different intersection with the company.

It wasn't until September 2015 that Delo experienced a moment of inspiration that would change their fate.

In repeatedly thinking about how to make leveraged trading easier for ordinary users, he gradually conceived a brand new derivative structure: a contract with no expiration date, which later became known as the "perpetual contract." By 2019, this innovation had propelled BitMEX to become one of the most profitable exchanges in the entire crypto industry.

It was also during this time, when this idea was continuously pushing the exchange to new heights, and before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, that I had a completely different kind of intersection with BitMEX.

A whistleblower from within the company reached out to me, hoping to disclose alleged regulatory violations by BitMEX. This person claimed that the founding team knowingly circumvented anti-money laundering regulatory requirements to boost profits. They mentioned that Bloomberg had already reported that regulators were investigating the company, but many key details had yet to be disclosed, and this information could be further provided to the Financial Times.

This lead did not progress very far. Just as I was preparing to investigate further, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, quickly consuming the entire news agenda. Further complicating matters, the source began to hesitate, fearing that providing evidence to the media might affect the overall case being pursued by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), and they did not deliver the materials I requested to verify the allegations. Before the Financial Times team could independently investigate, the market experienced severe turmoil, and the Financial Times itself was fully occupied by another major investigation involving money laundering, the Wirecard case.

Even so, what impressed me most during that encounter with the whistleblower was the internal contradiction presented in their narrative. This person clearly wanted to expose BitMEX's misconduct, yet at the same time, they maintained a notable respect for those they accused—repeatedly praising the company's professionalism, especially highly valuing Ben Delo's intellectual capabilities, particularly his core role in conceiving the "perpetual contract."

It was at that moment that I became firmly captivated by this concept.

Perpetual? What is it?

Before that whistleblower contacted me, I had never heard of the so-called "perpetual contract." This somewhat embarrassed me, as I had been reporting on commodity futures for years and considered myself familiar with the derivatives market. However, the operational mechanism of this new tool completely exceeded my intuitive understanding. I remember staring at BitMEX's trading interface, trying to dissect the logic within, but I clearly felt out of my depth.

As I began to experiment on the platform with my meager Bitcoin assets (worth about $10), the situation gradually became clearer. I started to realize that perpetual contracts were not merely a clever crypto trading tool. In a sense, they resembled a self-regulating LIBOR, a wholesale financing rate that was proven to be completely ineffective during the 2008 global financial crisis.

From this perspective, perpetual contracts suggest that a new financial architecture is forming, one that can bring clear price signals to a previously opaque and long-ignored financing market, especially reflected in intraday funding pricing.

What is truly striking is that the crypto industry itself has hardly realized what it has created. They clearly lack the knowledge and experience at the central bank level to understand how this tool fits into the evolving new paradigm of secured financing in the financial system.

I told myself: I must talk directly with Delo. I need to understand how he got to this point and want to know to what extent he understands the deeper "infrastructure issues" behind the dollar system.

Unfortunately, all my plans for this interview were soon interrupted by reality. Lockdowns, daily editorial work, column writing, and taking care of my young daughter consumed all my energy.

The truly decisive turning point occurred on October 1, 2020. Almost inevitably, things reached that point: Delo and his co-founders were formally charged with violating U.S. law, just as the whistleblower had previously predicted.

Frankly, I don't think the founders of BitMEX would have been surprised by the fact that "the whistleblower came from within." U.S. authorities have long operated a transparent whistleblower reward system, and the evidence disclosed during the trial clearly indicated that someone within the company was cooperating with the investigation. Perhaps what truly surprised them was that, in the months leading up to the formal indictment, their story had already been attempted to be provided to multiple media outlets.

In this context, any possibility of me continuing to track this story had vanished. BitMEX was mired in legal troubles, and the founders would inevitably fade from public view. Delo finally surrendered in New York in March 2021 and pleaded not guilty to the charges. In February 2022, in connection with the criminal proceedings related to the Bank Secrecy Act, all three ultimately chose to plead guilty. According to the final settlement terms, each paid a $10 million fine, and Delo was sentenced to 30 months of probation.

This was not the worst outcome. BitMEX had to fully implement KYC and AML systems to continue operating, but the three founders were able to retain the considerable wealth they had accumulated over the past few years.

By February 2022, I had left the Financial Times and founded Blind Spot. This meant that after nearly a year, or even longer, of limited topic selection, I could finally freely advance my editorial plans.

The new project still took several months to gradually get up and running, but eventually, I was able to return to this story. By then, BitMEX's legal issues had largely settled, and it seemed like the right time to contact Delo. I sent him a request; he hesitated at first but ultimately agreed to the interview.

So, on June 28, 2022, I sat in Delo's exceptionally simple office in Westminster, listening to him recount how he invented the perpetual contract. As we spoke, an old-fashioned floor clock chimed rhythmically in the background.

That conversation lasted nearly two and a half hours (or at least the clock chimed three times), almost entirely revolving around the twisted and complex technical details surrounding the birth of the perpetual contract.

More than three years have passed since that conversation. Readers may reasonably wonder: why has this complete story only emerged now? Frankly, the responsibility lies mainly with me and the various real-life demands brought about by the entrepreneurial process.

To do justice to this topic, I postponed formal writing time and again, always thinking I could finish it during some "10% time" that never truly materialized. Complicating matters further, I had previously promised Bloomberg that I would provide them with key parts of this story—because I believed Delo's experience deserved broader dissemination than just through Blind Spot.

That Bloomberg report was ultimately published on August 31, 2022. It was not the complete narrative I had originally hoped to write, but at least it confirmed that the most important facts had entered the public record, allowing me to save the full version for a time when I could truly focus.

Incredibly, that moment only finally arrived this past weekend, and the reason will soon become clear.

From one perspective, this delay may not be a bad thing. Compared to back then, the fragments of the story I now possess are much more complete. Moreover, as Douglas Adams, the famous procrastinator and author of "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," said: for creators, the hardest part to complete is often the last mile.

Origins

As mentioned earlier, the exploration of the "ultimate derivative" fittingly began in the back seat of a taxi in Shanghai in September 2015. At that time, Delo and Hayes were in China participating in a startup accelerator program while being troubled by the increasing user complaints about BitMEX's futures contracts. Although both were quite familiar with traditional derivatives markets, they gradually realized that crypto traders hated any tools with fixed expiration dates and were extremely averse to being forced to liquidate or roll over.

As someone trained in mathematics and engineering, Delo has always placed a high value on speed, certainty, and market structure.

Before founding BitMEX, he worked as a financial engineer at GSA Capital and JPMorgan, building trading algorithms and data systems. During his time at GSA, he worked directly with Alex Gerko—a Russian-born mathematical genius who later became one of the richest people in the UK.

Delo's interest in Bitcoin began around 2013, more out of intellectual curiosity than ideological passion. He told me that his first purchase of Bitcoin was motivated solely by a desire to better understand how the system worked. "As a new technology, it was very appealing to me, and I wanted to learn more about it."

However, this curiosity quickly collided with the chaotic reality of early crypto infrastructure. The exchanges he encountered were slow, structurally weak, and often faced catastrophic failures. Too many platforms suffered severe damage due to operational errors or direct hacking, with trust repeatedly eroded, making it nearly impossible for anyone accustomed to professional trading standards to truly use the entire market. Delo soon realized that the technological potential of this industry was being stifled by its own terrible "infrastructure."

For a long time, Delo tried to avoid these risks. His preferred way of acquiring Bitcoin was through LocalBitcoins, an early peer-to-peer trading platform that allowed buyers and sellers to meet face-to-face, thus avoiding many systemic pitfalls. It was also on LocalBitcoins that Delo met Arthur Hayes: a trader with a background in equity derivatives trading at Deutsche Bank and Citibank, and a finance background from Wharton.

The two hit it off almost immediately, as they shared a highly consistent judgment about the deep structural flaws in the crypto market and understood the costs required to fix these issues.

They both noticed a fact that most people overlooked: almost no existing exchange truly understood the margin mechanism. They quickly realized that this represented a huge opportunity.

Not long after, Hayes proposed to Delo: to establish a derivatives exchange that would bring the mature margin discipline of traditional finance into the crypto market.

The two reached a clear division of labor: Delo would be responsible for building the system's technology and underlying mechanisms, while Hayes would handle financing and marketing. However, they still needed a software engineer, which is why Sam Reed, who was then residing in Hong Kong, was invited to join the team as the third co-founder of BitMEX.

In 2014, the three co-founded HDR Global Trading, the parent company of BitMEX, where "HDR" stands for Hayes, Delo, and Reed.

In this sense, Delo stated that the birth of BitMEX was always overshadowed by the collapse of Mt. Gox. This early crypto exchange "lost" 850,000 Bitcoins in 2014 and had not even realized the problem existed for quite some time.

Although the outside world did not immediately see the full picture, the failure of Mt. Gox was not due to a single catastrophic hacking incident but rather years of accumulated operational flaws. It was initially launched in 2010 as a modified website for trading "Magic: The Gathering" cards and rapidly expanded without mature infrastructure. Its matching engine and wallet system were known for their fragility, and between 2011 and 2013, accounting loopholes, unrecorded withdrawals, and exploitable system flaws (the most famous being the "transaction malleability" issue) gradually created a massive but nearly invisible gap in customer assets.

On February 28, 2014, Mt. Gox filed for bankruptcy, and the loss of approximately 650,000 to 850,000 Bitcoins was exposed, shocking the entire crypto community. Initially, almost everyone suspected it was a scam or a hacking attack—including the exchange's own owner. However, as the investigation deepened, it became clear that these losses were actually the result of years of slow accumulation, caused by "drip theft," human error, and poor reconciliation mechanisms.

The founders of BitMEX thus reached a consensus: their trading platform had to be designed tightly enough to ensure that another Mt. Gox could never happen.

To achieve this, Delo proposed a core principle: the BitMEX system must be able to reconcile to zero at any moment. "I designed BitMEX's trading engine to ensure it would never lose even a penny," he explained, emphasizing that to this day, the system has never lost even a single satoshi. "If it's not zero-sum, it means you've created or destroyed Bitcoin out of thin air—this is impossible."

To accomplish this, BitMEX introduced a real-time auditing mechanism to ensure that at any moment, the number of Bitcoins recorded by the trading engine matched exactly the amount actually held in the exchange's wallet.

In theory, such a rigorous design should have easily impressed investors.

However, when the three tried to raise funds, they found they had chosen the worst possible time to start a crypto exchange. It was the depths of the "crypto winter" in 2014, when venture capital had almost completely withdrawn from exchanges and all Bitcoin-related fields. The most popular narrative at the time was "enterprise blockchain," not trading infrastructure, so almost no one was willing to bet on them.

Delo recalled in a face-to-face interview in 2022: "When we came out in 2014, exchanges already existed, and VCs had already invested. Arthur went to find investors, and they seriously said, 'Oh no, we're not investing in Bitcoin anymore; we're investing in blockchain.' We asked, 'So what is blockchain?' And they couldn't explain it themselves."

In a situation of scarce funding and almost zero attention, the founders had no choice but to dig into their savings and fully rely on self-funding to launch BitMEX.

The team visited Sam Reed in Milwaukee. Photo provided by BitMEX.

Ironically, the absence of external capital later became an advantage. Unlike most exchanges, BitMEX was almost always firmly in the hands of the founding team. By 2018, when the platform's annual profit approached $1 billion, the ones truly sharing the rewards were not a host of venture capital firms, but the three founders themselves.

In 2019, BitMEX's annual trading volume reached $1 trillion, and Delo's 30% equity stake was valued at $3.6 billion.

In 2014, Arthur Hayes, Ben Delo, and Sam Reed at the Web Summit. Photo provided by BitMEX.

However, the founding team's first major breakthrough did not actually come directly from the perpetual contract, but rather from something more crude and intuitive: extreme leverage.

Delo and Hayes were well aware that in traditional financial markets, retail traders typically could only use 2x to 3x leverage—investing $1,000 often only allowed them to establish a position of $2,000 or $3,000. But they believed that the crypto market could handle a more aggressive risk exposure without jeopardizing the overall safety of accounts.

This judgment ultimately led to the design of "isolated margin": each trade would be isolated in a separate margin pool, completely severing it from the rest of the account's funds.

In this model, a failed trade could no longer drag down the entire account. As a result, a trader with only $100 could control a position worth $10,000; even if the market moved against them, losses would be strictly limited to the margin they had already invested. Even a small fluctuation in Bitcoin's price could create or erase wealth, but the risk boundaries remained clear.

This safety net seemed logically conservative, yet it effectively encouraged more aggressive betting and significantly increased trading frequency. This was crucial for BitMEX, as most of the platform's revenue came from trading fees.

Delo recalled that on the day BitMEX officially raised the leverage limit from 50x to 100x, trading volume exploded. It was also on that day that the exchange finally became profitable.

The core of this "magic formula" lay in the real-time margin system designed by Delo.

"Every time the mark price changes, we immediately recalculate every position and every trader's margin status," he explained. "We can instantly determine whether a position needs to be liquidated. If it does, the liquidation happens immediately—not a few minutes later through a manual process, but before the price moves further in an unfavorable direction."

Many exchanges at the time already had forced liquidation mechanisms, but BitMEX's key innovation was making the liquidation process cheaper and more orderly. Importantly, the trigger for liquidation was not BitMEX's own internal price—which could be distorted due to lack of liquidity—but rather an independent third-party price index. This design effectively prevented cascading sell-offs and spared the platform from being adversely affected by its own market shocks.

"No one likes to be liquidated," Delo said, "but we try to make the rules clear and transparent, so at least there won't be any surprises."

This system quickly gave rise to the phenomenon of "involuntary liquidation." In the crypto circle, it is more commonly referred to as "getting rekt," and it gradually spawned a whole set of its own meme culture.

Towards Perpetual

Although high-leverage products achieved early success, by 2015, this futures-centric exchange still faced another type of problem. Part of it stemmed from the complexity of the derivatives themselves.

Retail crypto traders were not accustomed to the fixed expiration dates that futures contracts carried. Initially, like traditional markets, BitMEX launched Bitcoin futures with different expiration cycles, just as crude oil can have June and December deliveries. But like all futures markets, these contract prices would deviate from spot prices over time, reflecting market expectations of future supply and demand, as well as costs such as storage and financing. In traditional finance, the premium or discount of futures relative to spot is referred to as "basis."

However, despite these mechanisms being commonplace in traditional markets, the founders of BitMEX quickly realized that a large number of traders did not understand these dynamics. Worse still, this understanding barrier was becoming a limiting factor for users' further participation in trading.

It was during the aforementioned taxi ride in Shanghai that, while Delo and Hayes reviewed product flaws and discussed user feedback, Delo began to repeatedly ponder a question: Do futures contracts really need to have an expiration date?

He gradually realized that traders did not want to think about rolling over or understanding the basis. What they wanted was simply a clean, continuous, and uninterrupted exposure to Bitcoin's price.

If that was the case, why not simply create a futures contract that would never expire?

On the surface, this idea seemed almost absurd. Delo threw this concept to a friend who was into quantitative trading, and he was immediately met with skepticism: a contract without an expiration date would theoretically have an infinite fair value. "You have to take the interest rate factor out of it," that friend told him.

This statement triggered a deeper level of thought for Delo. Since traders did not want financing costs reflected in Bitcoin's price, why not completely strip it away? In his view, the cleanest way to do this was to pair each position with a dynamically changing funding rate.

The subsequent question was: how should this rate be determined?

Delo realized that for this mechanism to work, a market-driven benchmark interest rate needed to be introduced—a reference indicator that played the role of LIBOR in the crypto market. But in 2015, such a thing did not exist. The closest alternative was the borrowing rates on spot exchanges like Bitfinex and Poloniex: users lent dollars or Bitcoins on these platforms to fund long and short trades. It was not perfect, but at least it could serve as a starting point.

This was the initial breakthrough that allowed perpetual contracts to truly launch.

When the first version of the perpetual contract went live in May 2016, traders flocked in with almost a fervent attitude. Trading volume quickly hit new highs. Many viewed this product as something almost "magical": it had all the leverage advantages of futures without the hassle of rolling over. Compared to the previously complex derivatives, its operational logic was much more intuitive.

At the same time, the series of weekly and daily futures contracts that BitMEX originally offered, with complex codes like XBT 7D, XBT 48h, and XBT 24h, became redundant.

"We cut all of those and kept just one contract, called XBT USD," Delo recalled.

This simplification also brought an unexpected positive effect: liquidity became highly concentrated, significantly improving BitMEX's market depth and trading efficiency, achieving multiple benefits at once.

Pricing for Liquidity

Undoubtedly, traders loved this product. The problem was that they loved it a bit too much.

Despite the introduction of funding rate adjustments, the prices of perpetual contracts began to consistently exceed spot prices, sometimes with premiums reaching 5% or more. This indicated that the funding rates constructed from third-party lending data had begun to lag behind the real market conditions.

In Delo's view, this posed a serious problem: traders who established long positions using only 1% margin could easily be liquidated if the perpetual contract price quickly fell back to spot levels. Worse still, these traders might believe that their liquidation was triggered by a "disconnected price," leading them to question the fairness of the system.

To address this issue, Delo's first reaction was to approach market makers, reminding them that when the perpetual contract deviated from spot by 5%, shorting and bringing the price back on track was itself an almost risk-free arbitrage opportunity. But the market makers were not convinced; they believed the premium could easily expand further to 10% or even higher.

At this point, Delo realized that the real problem was not whether arbitrage opportunities existed, but that the funding rate itself was insufficient to attract enough shorts into the market.

He needed to design a new mechanism that would allow the rate to adapt to the degree of market deviation.

The specific approach was to measure the deviation of the perpetual contract price from the spot price on a minute-by-minute basis. This deviation value later became known as the "premium index" and was used to determine the funding rate. The rate would be updated every 8 hours and automatically settled at each cycle, payable in Bitcoin or stablecoins.

"This was the first time we used our own market data to build an index," Delo said.

Mechanically, the funding rate was determined by the BitMEX perpetual contract price and its premium relative to the spot index. However, to enhance robustness, Delo did not simply rely on the transaction price but calculated a depth-weighted price spread based on the mid-price of the entire BitMEX order book. This value was then hedged against the contract's current "fair price," which was derived from the Bitcoin spot price plus the basis implied by the previous period's funding rate.

This system essentially "forecasted" the funding rate for the next 8 hours. In most cases, the rate remained positive, reflecting the market's natural bullish preference while attracting shorts through economic incentives to correct price deviations.

"Shorts often enter early to earn that 1% profit, then choose to hold, close, hedge, or do other operations," Delo said. "The key is that their actions themselves would push the premium down."

As a result, a positive feedback loop was formed.

When longs pushed the perpetual contract price above the spot, the holding costs rose rapidly; when shorts dominated, the funding rate would decrease accordingly.

Delo described this mechanism as a "dynamic mechanism for pricing liquidity": when market demand tilted in one direction, the funding rate would drive traders to act in the opposite direction, bringing prices back into a reasonable range, thus keeping the perpetual contract closely aligned with the spot.

"If you break down this system mathematically," he explained, "we essentially eliminated the overnight interest rates of Bitcoin and the overnight interest rates of dollars. They are just shadows left over from the evolution of the system. Ultimately, the funding rate is entirely determined by the product's premium relative to the spot. This is dynamic pricing."

For BitMEX, the perpetual contract quickly became its signature innovation.

Trading activity exploded rapidly. In just a few years, "perp" evolved from a niche experiment into a standard tool in the market. Initially just BitMEX's flagship product, it was soon replicated across the industry, ultimately becoming the default way for traders to gain leverage in the crypto market.

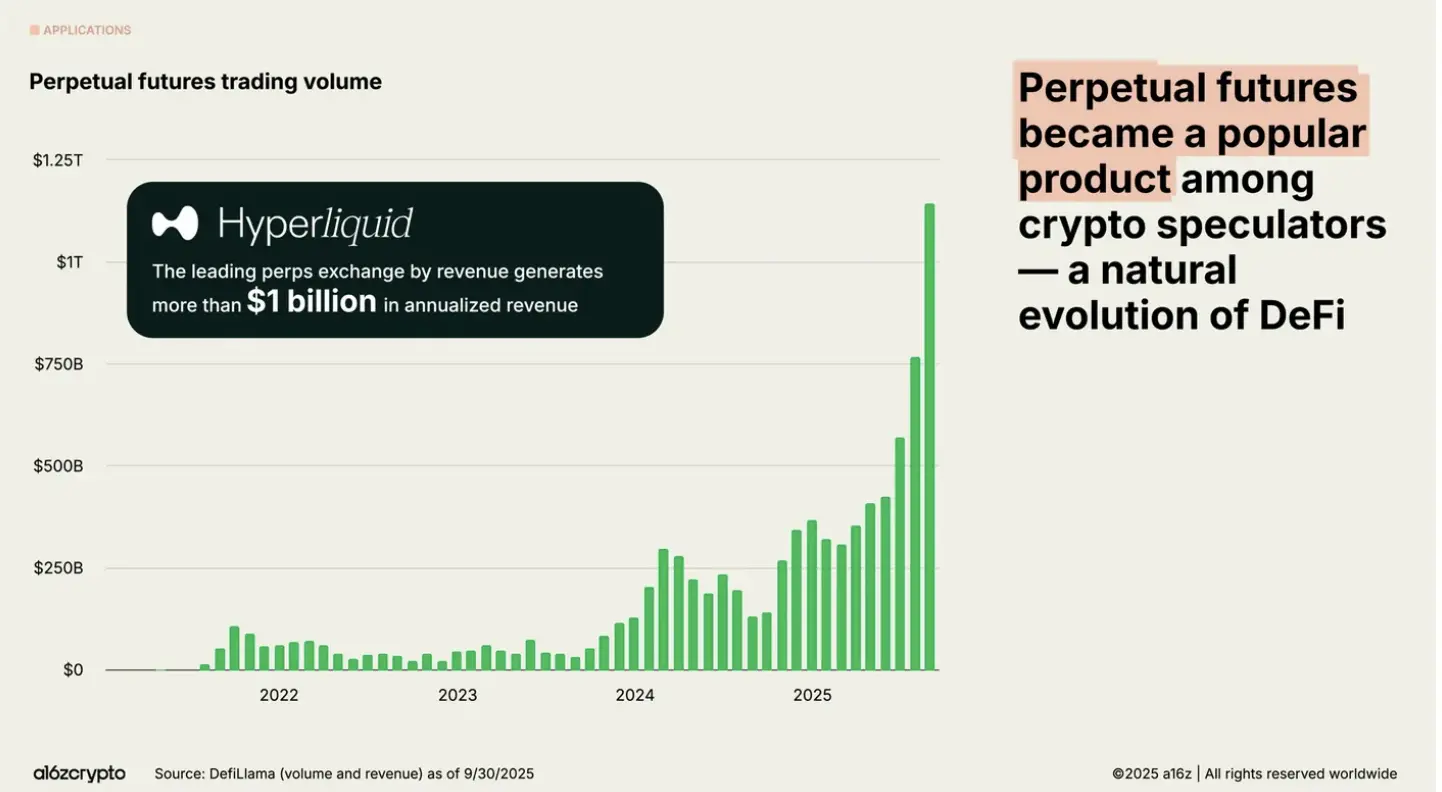

As shown in the chart from a16zcrypto below, perpetual contracts have now become the foundational trading unit in the DeFi industry, carrying daily trading activities worth trillions of dollars.

A Shadow Rate?

For quite a long time, Delo had not thought about the broader applications of perpetual contracts from a macro perspective.

"We were just trying to solve a user problem at the time," he said, mentioning that after the concept took shape, he completed the entire mechanism in just a three-hour flight from Singapore to Hong Kong. "Once this thing was invented, it ran so smoothly that I could hardly believe it hadn't existed before," he recalled.

In Delo's view, perpetual contracts themselves do not possess any inherent attributes that must be based on Bitcoin. The same structure could be applied to stocks, gold, crude oil, or any other asset with sufficient spot liquidity, including the dollar itself—perhaps in a form similar to an overnight index swap (OIS).

In all these scenarios, a similar result would ultimately emerge: a nominally "secured," but in practice highly leveraged offshore financing rate. Theoretically, it could be applied to any asset class with an active spot market.

The operational logic is highly consistent across various assets: when the funding rate of perpetual contracts rises significantly, the market is actually sending a signal that one can earn returns by taking the opposite side of the trade.

This means that in the offshore system, the demand for leveraged exposure is exceeding the dollar liquidity that the system can provide; anyone willing to provide this liquidity can thus earn substantial returns.

The key is that because this demand itself is highly leveraged, when it arises, a new demand for U.S. Treasury bonds, exceeding the traditional constraints of lendable funds, will also be created simultaneously.

The deeper implication is that this shadow-like "liquidity price" exists entirely outside the control of the Federal Reserve.

Therefore, as long as the funding rate of perpetual contracts is significantly higher than the Federal Reserve's policy rate, the arbitrage path becomes clear: borrow dollars from the banking system at a lower policy rate, convert them into stablecoins, and then capture higher synthetic returns in the perpetual contract market. This process will attract new demand into the stablecoin system and, through its reserve managers, further flow into U.S. Treasuries (especially short-term T-bills).

Conversely, if the Federal Reserve raises the policy rate above the funding rate of perpetual contracts, the incentives will reverse: stablecoins will be redeemed, issuers will have to sell Treasuries to meet withdrawal demands, and the marginal buyers of short-term government bonds will disappear.

In this sense, the funding rate of perpetual contracts could become both a "lower bound" and an "upper bound" for U.S. monetary policy, a shadow rate that reflects the true marginal cost of dollar liquidity faced by any trader who can access the stablecoin system. When it is too high relative to the policy rate, it will siphon liquidity from the banking system towards the crypto market and Treasuries; when it is too low, it will trigger a deleveraging process and negatively impact the Treasury market.

Furthermore, if an exchange were to launch perpetual contracts based on the dollar itself, then its funding rate would become a pure measure of "stablecoin-based dollar scarcity," a crypto-native LIBOR. Technically, it might be "unsecured," but its level would be shaped by the collateral conditions in a highly leveraged market. It would not converge to the Federal Reserve's policy rate but would reveal the true marginal cost of offshore dollar liquidity, unaffected by direct control from the Federal Reserve.

Of course, in the long run, markets tend to move towards equilibrium. If the funding rate of perpetual contracts supported by stablecoins remains significantly higher than the policy rate for an extended period, arbitrage activities should eventually withdraw enough liquidity from the core banking system, bringing it into the stablecoin-perpetual contract structure, causing both to gradually converge. However, this convergence would come at the cost of weakening the Federal Reserve's regulatory capacity, as liquidity begins to flow into jurisdictions not bound by the Basel Accords.

A more likely scenario is that the Federal Reserve will do everything it can to limit this arbitrage path, just as it did with the Eurodollar market after the financial crisis. If the U.S. Treasury simultaneously refuses to issue additional T-bills beyond its own financing needs or debt ceiling constraints, then the funding rate of offshore perpetual contracts will be institutionally maintained at a high level.

In such an environment, the only entities capable of expanding the "synthetic dollar supply" will be those foreign official or semi-official institutions that already hold large amounts of U.S. Treasuries—such as China, Japan, and other countries. If the funding rate of perpetual contracts remains high for an extended period, they will be strongly incentivized to issue their own dollar stablecoins and lend them into the perpetual contract market to achieve liquidity and arbitrage of reserve assets.

If, through some unexpected channel, the two systems truly achieve covered interest rate parity (i.e., aligning the funding rate of perpetual contracts with the Federal Reserve's policy rate), then the power of perpetual contracts will become even clearer outside the crypto market.

Take gold as an example: if perpetual contracts are launched with tokens pegged to physical gold, such as XAUT, the forward rates generated by its funding rate may be more accurate and transparent than the opaque system currently constituted by CME futures pricing and private interbank precious metal lending quotes. The real, secured financing costs for gold in the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) are still largely hidden behind the scenes and will be exposed to public view in real-time for the first time.

In Delo's view, this transparency is precisely why most traditional financial platforms remain hesitant about the perpetual contract model. It not only compresses their profit margins but also places the economic structure of their own financing markets under public scrutiny.

"What makes this contract truly unique is that it is a market in itself, a dynamic market," Delo said. "It does not require the platform itself to put in capital, nor does it need the platform to act as a market maker. It will naturally attract market makers, buyers and sellers, longs and shorts, price takers and price makers, bringing everyone together into the same system."

The ultimate irony is that a mechanism originally designed to keep derivative prices closely aligned with spot prices may, in the future, exert gravitational pull on the entire dollar system itself.

Defender of Free Speech

This is not the end of my story with Ben Delo.

Many readers may know that I have long been involved in the free speech community. In my view, this is a topic that a journalist can openly support without worrying about compromising professional neutrality. Because free speech itself does not contradict the most basic responsibilities of the journalism profession.

Therefore, when in the summer of 2023, I still felt guilty for not having completed this article, I was somewhat surprised to walk into Delo's office in Westminster again. This time, I was invited to attend a gathering focused on free speech, and what shocked me even more was that the event was hosted by Delo himself. Before that, I had no idea he had been funding this cause behind the scenes. Frankly, the awkwardness of that moment left me feeling embarrassed.

Fortunately, The Daily Telegraph has done a far better job of telling his story than I have. Just last week, they provided timely and detailed coverage of Ben Delo's work in the field of free speech, which ultimately prompted me to resolve to complete this long-overdue article.

If I had to find a reason for this delay, it would probably be that today's writers face oppression not only from government orders, defamation threats, or legal battles, but also from the scarcity of time itself. When you have to "sing for your supper" in institutions that pay the bills and follow their editorial priorities, those passion-driven writing projects are bound to be pushed further back.

Sometimes, what prevents a story from being told is not censorship, but the cost of life itself.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。