The current gold is less of a money-making tool and more of a money-losing insurance.

Author | Ding Ping

Can gold, which has "soared to the sky," still be allocated?

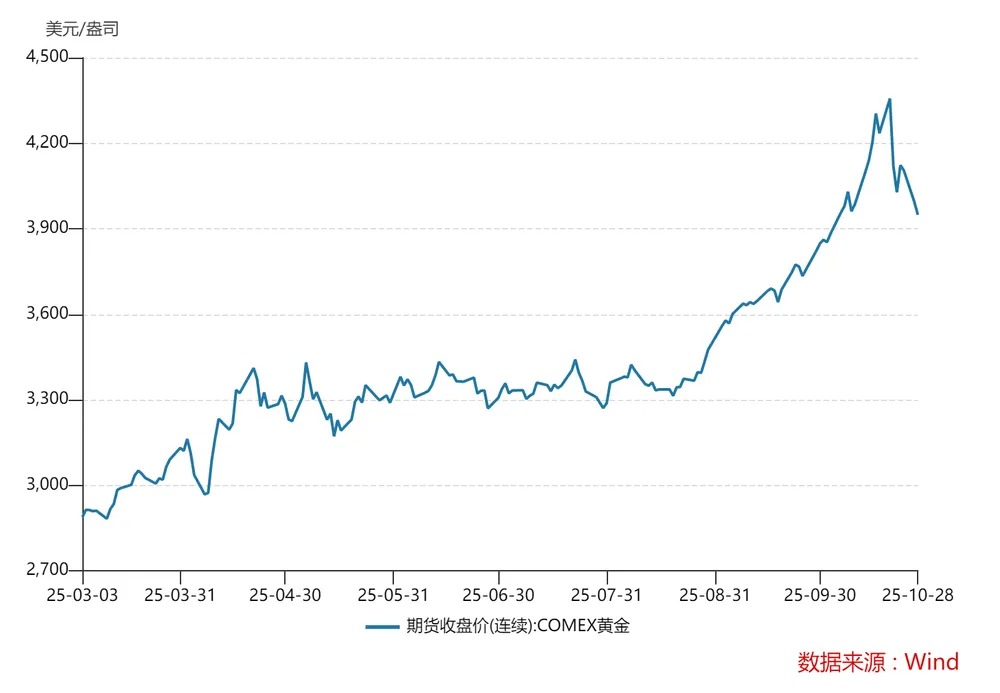

This year, gold has surged sharply, with international gold prices skyrocketing from $3,000/ounce to $4,000/ounce in just seven months. On October 20, COMEX gold hit a historical peak of $4,398/ounce, but the following evening it plummeted by 5.07%, marking the largest single-day drop since its listing; the downward trend continued, and by October 29, it had fallen below the $4,000/ounce mark, retracting nearly 10% in just eight trading days.

Bearish voices in the market have begun to increase. According to CME Delta exposure data, approximately 52,000 put options have accumulated in the $4,000-$3,900 range.

There are also rumors that Philippine banks intend to sell gold. Benjamin Diokno, a member of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank of the Philippines and former central bank governor, recently stated that their gold holdings account for about 13%, higher than most central banks in Asia. Diokno believes that the ideal gold reserve ratio should be maintained in the range of 8%-12%.

This statement has been interpreted by the market as a potential signal for reduction, further strengthening bearish sentiment. Has gold really peaked?

To conclude, gold has not yet peaked, but it has passed the stage of explosive growth. The current gold should be viewed more as a money-losing insurance rather than a money-making tool.

Gold as a Reflection of Energy Order

In the modern credit currency system, the reason the US dollar can become the global settlement currency is not only due to its powerful military and financial network support but also because it controls energy pricing. As long as global energy transactions must be settled in dollars, petrodollars become the core of this system.

In 1974, the US signed a key agreement with major oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia: all global oil transactions must be settled in dollars. In exchange, the US promised to provide military protection and economic support. Since then, oil has become the "new anchor" of the credit currency era. As long as energy prices remain stable, the credit of the dollar remains stable.

Because when energy costs are controllable and production efficiency continues to improve, inflation is hard to rise, which can provide "favorable conditions" for the expansion of the dollar system.

In simple terms, if the economy is growing rapidly and inflation is low, the return on dollar assets can cover the speed of dollar issuance, and gold will naturally become less attractive.

This also explains a phenomenon: at certain times, the increase in gold prices lags far behind the speed of dollar printing. The Federal Reserve's balance sheet has expanded nearly ninefold since 2008 (as of the end of 2023), while gold prices have only increased by about 4.6 times during the same period.

Conversely, when energy is no longer a shared efficiency dividend but becomes a strategic resource weaponized by various parties, the physical system that supports the expansion of the dollar through stable, low-cost energy begins to loosen. The credit of the dollar cannot be maintained with low-cost goods, and gold, as a zero-credit risk asset, will naturally attract capital back.

This is why every time there is turmoil in the energy order or a reassessment of energy costs, gold almost always enters a bull market.

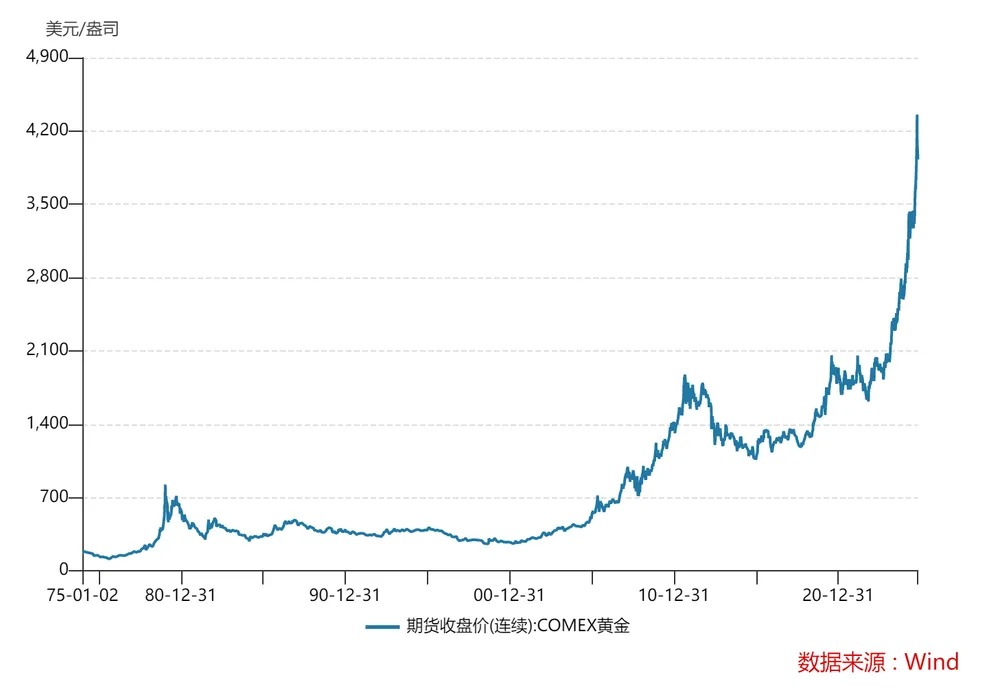

The highest increase in gold prices in history occurred from 1971 to 1980. During this decade, the price of gold rose from $35/ounce to $850/ounce, an increase of about 24 times. Three major events occurred during this period:

In 1971, the Bretton Woods system collapsed, and the dollar was decoupled from gold, which was no longer fixed at $35/ounce;

In 1973, the first oil crisis broke out. After the Middle East war, OPEC jointly limited production, and oil prices skyrocketed from $3 per barrel to $12;

In 1979, the Iranian revolution triggered the second oil crisis, and oil prices soared again to $40.

Coincidentally, the second highest increase in gold prices in history also occurred during a period of energy imbalance.

From 2001 to 2011, the price of gold rose from $255/ounce to $1,921/ounce, with an increase of 650%.

After the "dot-com bubble" burst in 2000, the US economy fell into recession in 2001, forcing the Federal Reserve to implement significant interest rate cuts starting in January 2001, reducing the federal funds rate from 6.5% to 1% by June 2003. During the same period, the dollar index fell from around 120 to about 85, a decline of approximately 25%, marking the largest depreciation since the floating exchange rate system began in 1973.

The depreciation of the dollar directly affected the reserve value of oil-exporting countries, forcing these countries to reduce their dependence on the dollar and turn to other currencies for settlement, such as the euro and the yuan. In 2000, the Central Bank of Iraq announced that it would price oil exports in euros starting in November 2001 (the "petro-euro"). In 2003, Iran also publicly studied the "Iranian Oil Exchange" to price in euros, and subsequently, from 2006 to 2008, Iran officially received payments in euros from European and Asian customers.

This trend of de-dollarization directly touched upon US energy financial interests. In 2003, the US launched the Iraq War, increasing global crude oil supply risks; from 2004 to 2008, energy demand from emerging economies like China and India surged. As a result, oil prices rose from $25 per barrel to $147 per barrel (mid-2008), and the uncontrollable energy costs led to imported inflation, decreasing the purchasing power of the dollar and driving gold prices to soar.

The most recent instance occurred from 2020 to 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic caused supply chain disruptions, and the Federal Reserve cut interest rates twice by a total of 150 basis points, returning to 0-0.25%, and initiated unlimited QE (quantitative easing); the Russia-Ukraine conflict triggered an energy crisis in Europe, with European natural gas TTF futures soaring, and Brent crude oil prices once approached $139 per barrel. Gold once again became a safe haven against systemic risk, with prices rising from $1,500/ounce to $2,070/ounce.

Therefore, the rise in gold prices is not only due to excessive currency issuance but also a result of the rebalancing of energy and the dollar system.

From Order to Disorder in the Market

As mentioned above, over the past few decades, globalization and technological progress have continuously created "negative entropy"—new production capacity, higher efficiency, and wealth accumulation. People are more willing to invest money in businesses and markets rather than in gold, which does not generate interest.

However, once this "negative entropy" supply chain shows cracks, such as uncontrollable energy prices, capacity transfer, or technological decoupling, new production capacity and efficiency dividends will disappear, and the system will shift from "negative entropy" to "entropy increase."

(Note: "Entropy" in physics represents the degree of disorder; in economics and monetary systems, it corresponds to efficiency decay, resource waste, and credit dissipation; "negative entropy" means system organization, improved production efficiency, and smooth energy circulation; "entropy increase" means rising prices, uncontrolled expectations, and the system moving from order to chaos, making the world "lively but inefficient.")

As long as this entropy increase process continues, meaning market efficiency declines and inflation spirals out of control, there will be support for rising gold prices. Currently, the disorder in the market is still ongoing.

The most direct manifestation is that fiscal deficits and monetary expansion are rising year-on-year, and national credit is being gradually overdrawn.

After the pandemic, countries' finances have fallen into a cycle of "spending more and becoming poorer," with government spending difficult to shrink, and debt rollover becoming the norm. The US fiscal deficit has long accounted for over 6% of GDP, with the annual net debt issuance expected to exceed $2.2 trillion, while the Federal Reserve's balance sheet, despite experiencing a reduction, still stands at several trillion dollars.

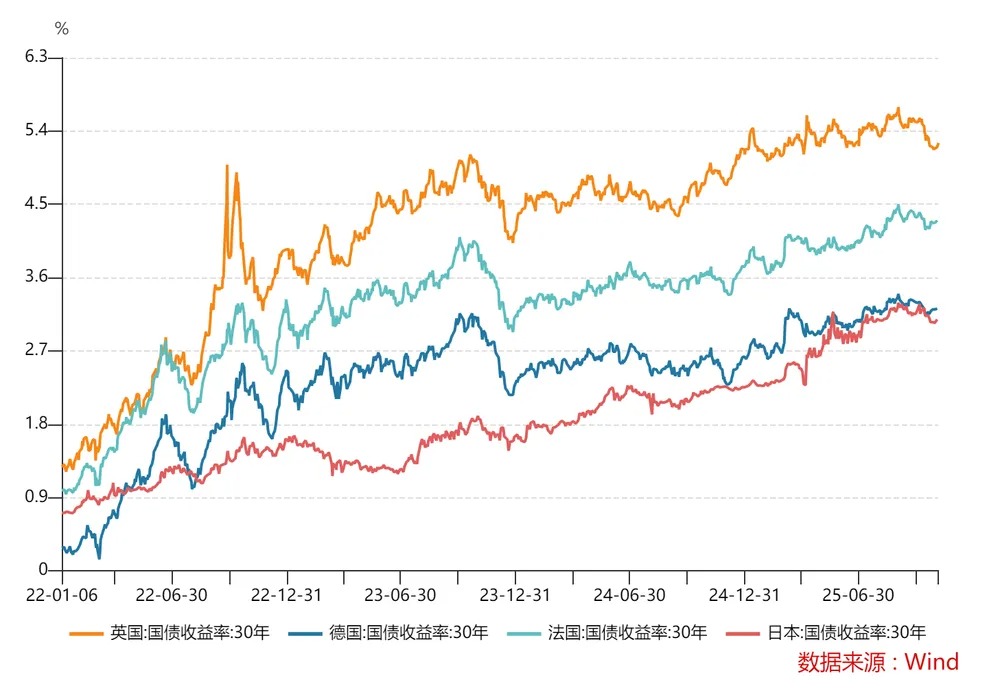

Other major economies are also facing unprecedented fiscal pressures by 2025—Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio is as high as 250%, and the overall fiscal deficit rate of the Eurozone is 3.4%, exceeding the limit for four consecutive years, with France, Italy, and Spain's deficit rates at 5.5%, 4.8%, and 3.9%, all above the 3% red line.

This also explains a seemingly contradictory phenomenon: against the backdrop of loose monetary policy, global 30-year long bond yields continue to rise, primarily due to market concerns about high future inflation and the government's inability to effectively control fiscal deficits, leading to higher compensation requirements for long-term risks.

In fact, this high debt situation is also difficult to reverse. Because in the new round of global technological competition, countries are strengthening fiscal spending to maintain strategic investments. Especially for China and the US, AI has become a crucial part of their competition.

China has clearly stated in its recent "Document No. 15" that technological innovation, emerging industries, and new productive forces are key breakthroughs for China to achieve "leapfrog development" in the future. This means that technology and advanced manufacturing are not just industry issues but the core competitiveness of national strategy.

In this strategic competition, the US also has its own policy proposals. On July 23, 2025, the US government released "Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan," positioning AI as the intersection of technology, industry, and national security, and explicitly proposing to accelerate data center, chip manufacturing, and infrastructure construction.

Thus, both China and the US will inevitably mobilize national resources to develop AI, and fiscal spending cannot shrink, which means government debt will continue to increase.

In addition, the restructuring of resources and industrial chains is also driving up costs.

For the past few decades, the world economy has relied on efficient global division of labor and stable energy supply, with production in East Asia, consumption in Europe and America, and settlement mainly completed within the dollar system. But now this model is being impacted by geopolitical friction, supply chain decoupling, and carbon neutrality policies, making resource flow increasingly difficult. The costs of transporting a chip, a ton of copper, or a barrel of oil across borders are all rising.

As geopolitical conflicts become the new normal, countries are also increasing defense spending, stockpiling energy, food, and rare metals. The US military budget has reached new highs, Europe is restarting its military-industrial chain, and Japan is enhancing its defense capabilities through the "Defense Capability Enhancement Plan."

When military spending and strategic stockpiles crowd out fiscal space, governments are more inclined to use monetary means to raise funds, resulting in lower real interest rates and a decrease in the opportunity cost of gold (since gold is a non-yielding asset), thus increasing its relative returns.

When monetary expansion no longer creates wealth and energy flow is politicized, gold can return to the center of the monetary system, as it is the only physical asset that is accepted during wars and credit crises, requiring no credit backing and not relying on any resources.

The Logic of Gold Allocation Has Changed

It is clear that the long-term bullish logic for gold is very clear, but do not allocate gold based on old thinking.

In the past, gold was more often seen as an investment tool, but in this position, gold has only one allocation logic, which is as a hedging tool, especially to hedge against stock market risks.

Take gold ETFs as an example; the annualized returns from 2022 to 2025 are 9.42%, 16.61%, 27.54%, and 47.66%, with increasingly attractive returns. The driving forces behind this can be summarized in three points:

First, central banks have begun to gradually accumulate gold. Data from the World Gold Council shows that since 2022, the behavior of global central banks in purchasing gold has undergone a qualitative change, with the amount of gold purchased rising from an average of 400-500 tons per year to over 1,000 tons for the first time in 2022, maintaining high levels for several consecutive years. In 2024, the net gold purchases by global central banks reached 1,136 tons, the second highest in history.

This means that central banks have transformed from ordinary participants in the gold market to key forces influencing pricing, thereby altering the original pricing logic of gold to some extent, such as weakening the negative correlation between gold prices and the real yields of U.S. Treasury bonds.

Second, geopolitical conflicts are frequent. Events such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict and tensions in the Middle East not only directly stimulate risk-averse sentiment but also strengthen the long-term motivation for central banks to purchase gold. As a "stateless asset," gold inherently possesses advantages in risk aversion and liquidity, attracting funds in an environment where risk events are frequent.

Third, the Federal Reserve's policy shift. In July 2024, the Federal Reserve ended a two-year interest rate hike cycle and began to cut rates in September. Rate cuts directly benefit gold in two ways: first, they can lower the opportunity cost of holding gold; second, they are usually accompanied by a weakening dollar, which is favorable for dollar-denominated gold.

The long-term logic for gold remains solid—central banks are still buying, global structural risks have not been eliminated, and the dollar credit cycle is still in an adjustment period. However, in the short term, the driving forces pushing gold prices steeply upward are weakening. Future increases in gold prices may be more moderate and rational.

Although these factors still exist, their marginal impact is actually diminishing.

The trend of central bank gold purchases is expected to continue (95% of surveyed central banks plan to increase their holdings in the next 12 months), but the pace of purchases may become more flexible due to gold prices being at historical highs; geopolitical uncertainties have become the new normal, which will continue to provide support for risk aversion, but the market's "sensitivity" to single events may decrease due to habituation; and the easing of Federal Reserve monetary policy has already been priced in by the market, so the intensity of the rate cut's positive effect may not be as strong as before and after the start of the rate cut cycle.

From an allocation perspective, if investors expect gold to continue delivering the rich returns seen from 2022 to 2025, the probability is actually quite low. It can only be said that gold prices are far from peaking, and Goldman Sachs has also raised its 2026 gold price forecast to $4,900/ounce. However, the slope of future gold price increases will not be as steep as before, especially in the current environment of relatively loose liquidity and high market risk appetite, where risk assets (stocks, commodities, cryptocurrencies, and futures options, etc.) have greater opportunities and are more likely to achieve high returns.

It is important to note that while risk assets rise quickly, they can also fall sharply. The biggest risk in the current stock market comes from macro-level uncertainties, such as escalating U.S.-China trade frictions, worsening geopolitical conflicts, or a potential recession in the U.S. Once these gray rhinos appear, risk assets will inevitably face significant corrections, and funds will flow into safe-haven assets, with gold being the most representative safe-haven asset.

Conversely, when these risks improve marginally, gold prices may correct, but risk assets will rebound. For instance, the recent sharp drop in gold prices was primarily triggered by a sudden cooling of risk-averse logic. Therefore, gold can form a perfect hedging relationship with risk assets (especially the stock market).

Overall, gold has not yet peaked, but it has passed the explosive growth phase. The role of gold in investment portfolios should shift from "high-yield asset" to "hedging tool."

When the stock market is volatile, gold is your safety rope.

But how should ordinary people allocate gold? The most common methods include physical gold bars, gold ETFs, and accumulated gold, each with its pros and cons. However, with the introduction of new tax policies on gold, the advantages of gold ETFs have become apparent.

On November 1, the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation issued an announcement regarding tax policies related to gold, clarifying new tax regulations for gold transactions from November 1, 2025, to December 31, 2027.

If you buy physical gold through non-exchange channels (not through the Shanghai Gold Exchange), the cost will be significantly higher because such transactions fall under the scope of value-added tax (VAT) collection, facing a 13% VAT cost, which merchants will likely pass on to consumers; whereas ETFs are classified as "financial products," continuing to be exempt from VAT, and their inherent high liquidity and transparent costs further amplify their trading cost advantages.

In terms of investment strategy, we recommend that investors focus on buying low and avoid chasing high prices.

Always remember: In an unpredictable market, gold is not a money-making tool, but a tool for safeguarding wealth.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。