The ideal of DAO is becoming a castle in the air.

Author: Firefly

11 years ago, the Ethereum white paper first outlined the prototype of DAO—a governance utopia where "code is law," and everyone participates and shares.

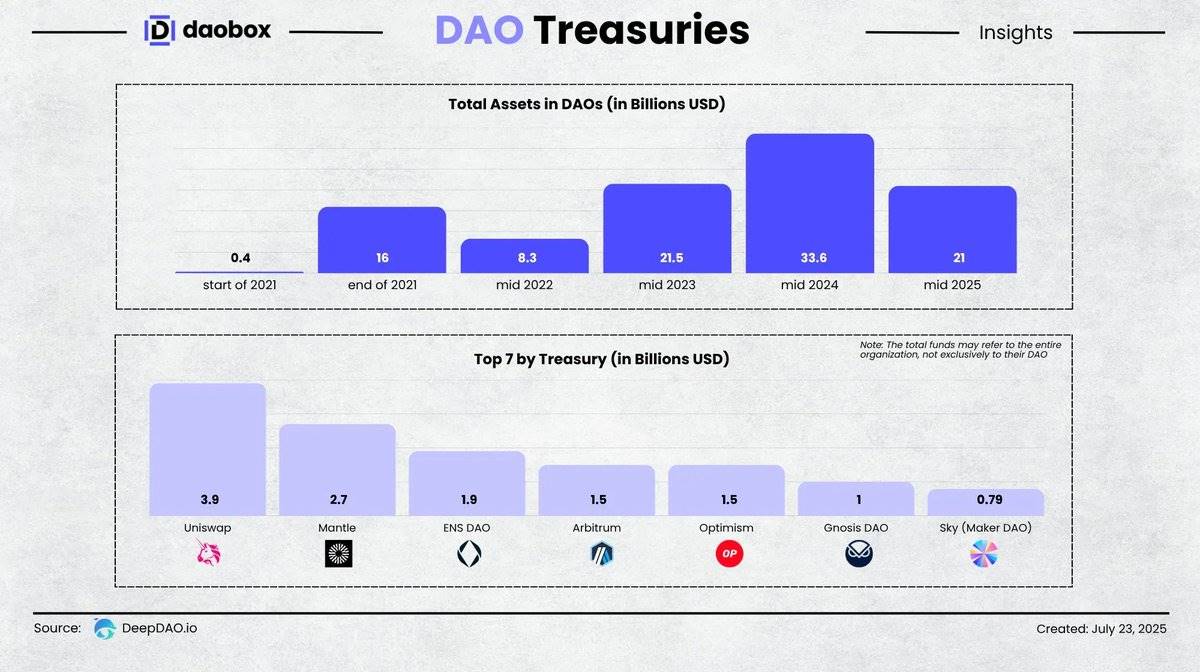

As of today in 2025, DAO has transitioned from concept to practice: Uniswap, Arbitrum, Lido, Nouns DAO, and others are operating daily. The peak assets managed by DAOs once reached $33.6 billion, and even after the market correction, there are still about $21 billion.

Data source: @DeepDAO_io

It sounds like the golden age of DAOs. However, behind the data lies a dangerous paradox: the more funds accumulate, the fewer participants there are.

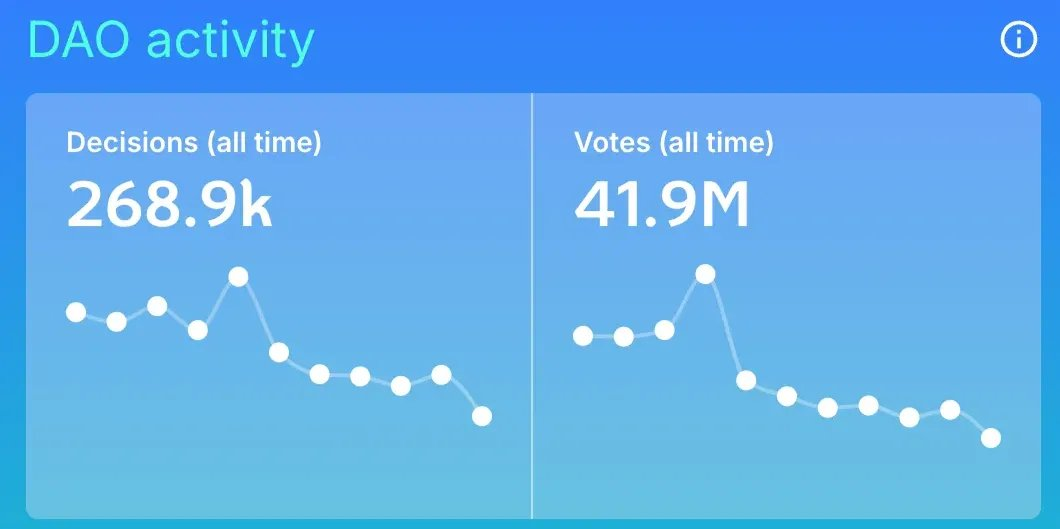

Data from @DeepDAO_io shows that by the end of 2024, the proposal and voting activity of DAOs peaked and has been declining month by month.

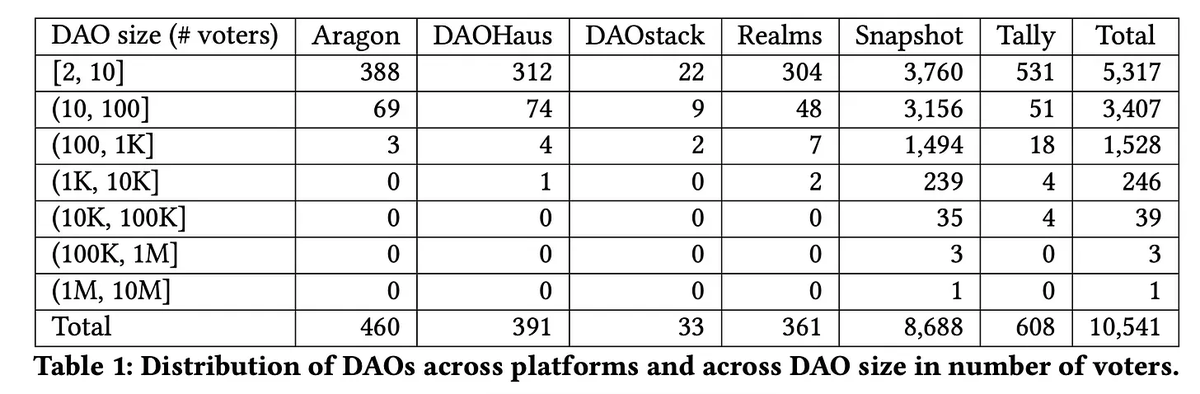

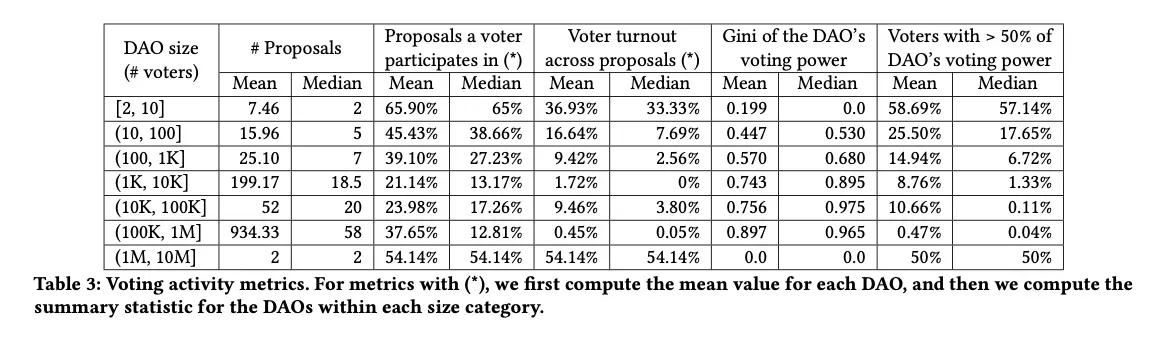

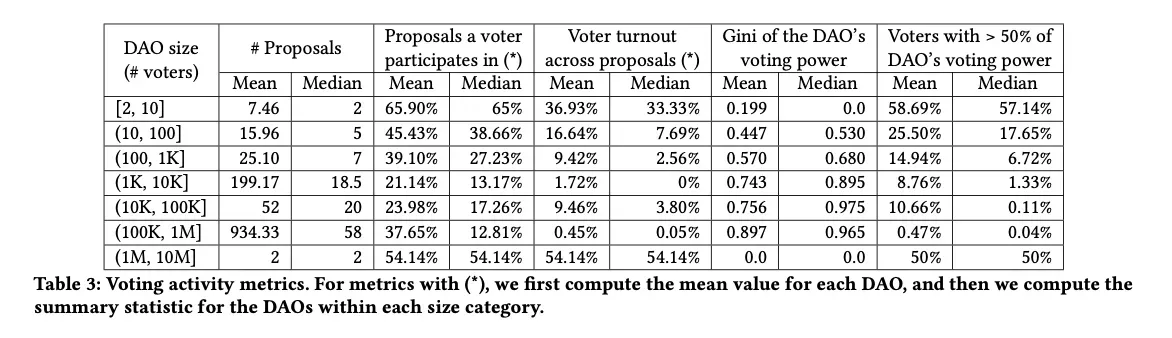

At the same time, an academic study published by the Complutense University of Madrid in May 2024 also confirmed two core issues of DAOs:

1. Extreme concentration of DAO voting participants:

About 50% of active DAO voters are fewer than 10 people

Only 300 DAOs have more than 1,000 voters, and only 4 DAOs have over 100,000 voters

2. Inverse relationship between DAO participation rate and scale:

The larger the DAO, the lower the participation rate. In large-scale DAOs, the number of token holders is vast, but most people hardly participate in governance.

Even in small DAOs (2–10 voters), the average participation rate is only 33.3%

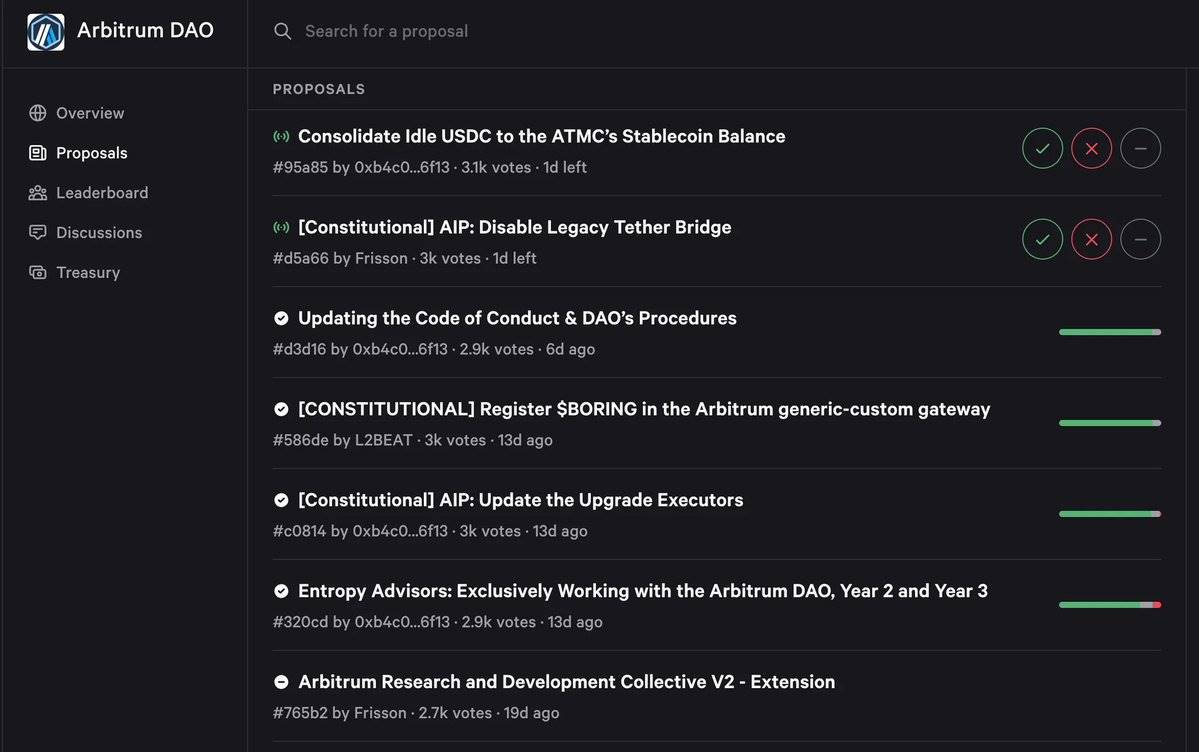

Taking Arbitrum as an example, this DAO, with a funding scale of $1.6 billion, 1.2 million token holders, and 487 proposals, seems large and active.

Data source: @DeepDAO_io

The reality is: the average number of voters per proposal is less than 3,000, with a participation rate of less than 0.3%.

Data source: Snapshot

This means that DAOs are "decentralized" in form, but in practice, they have become "well-funded zombies," with governance power highly concentrated, even harboring risks of governance attacks.

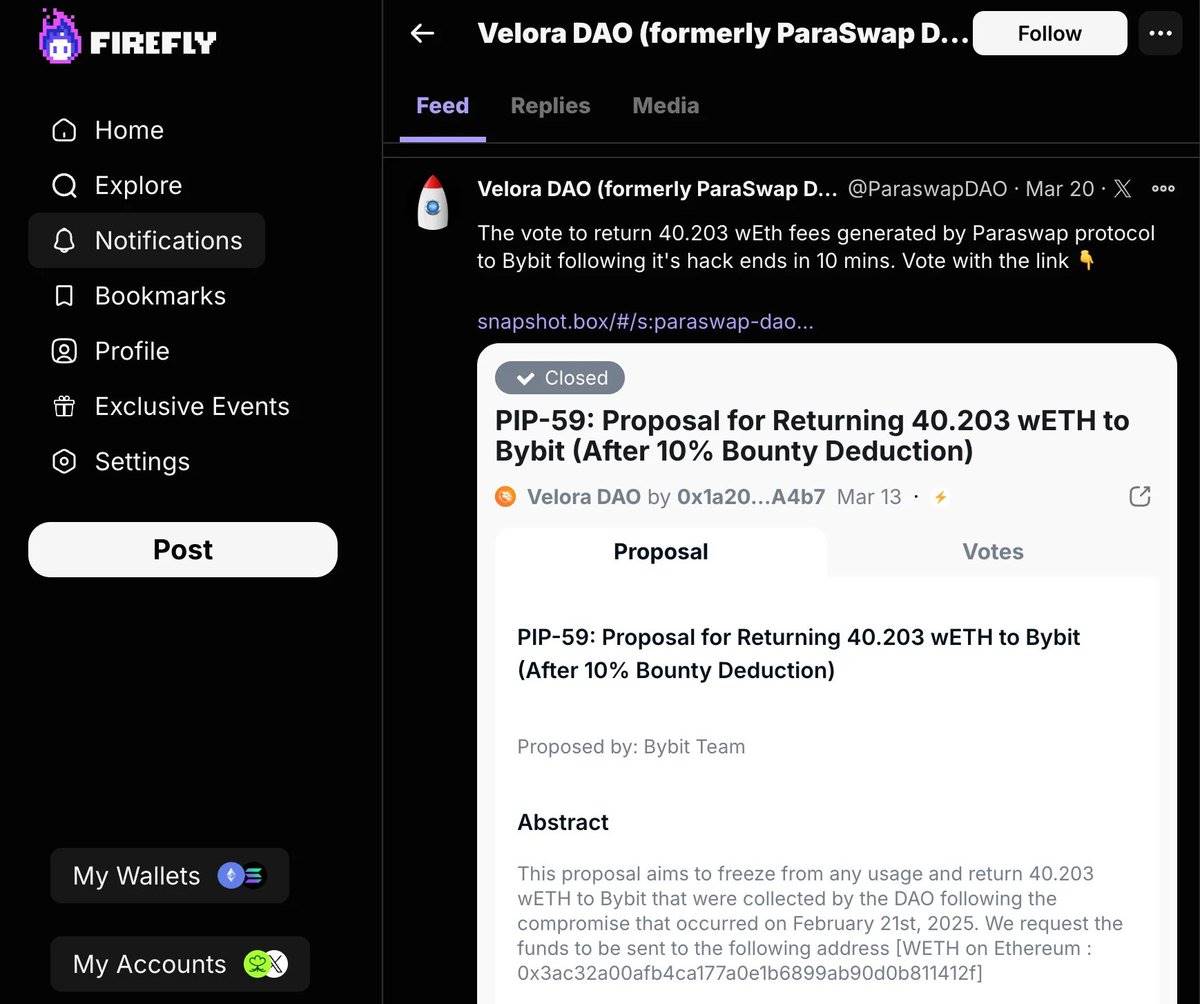

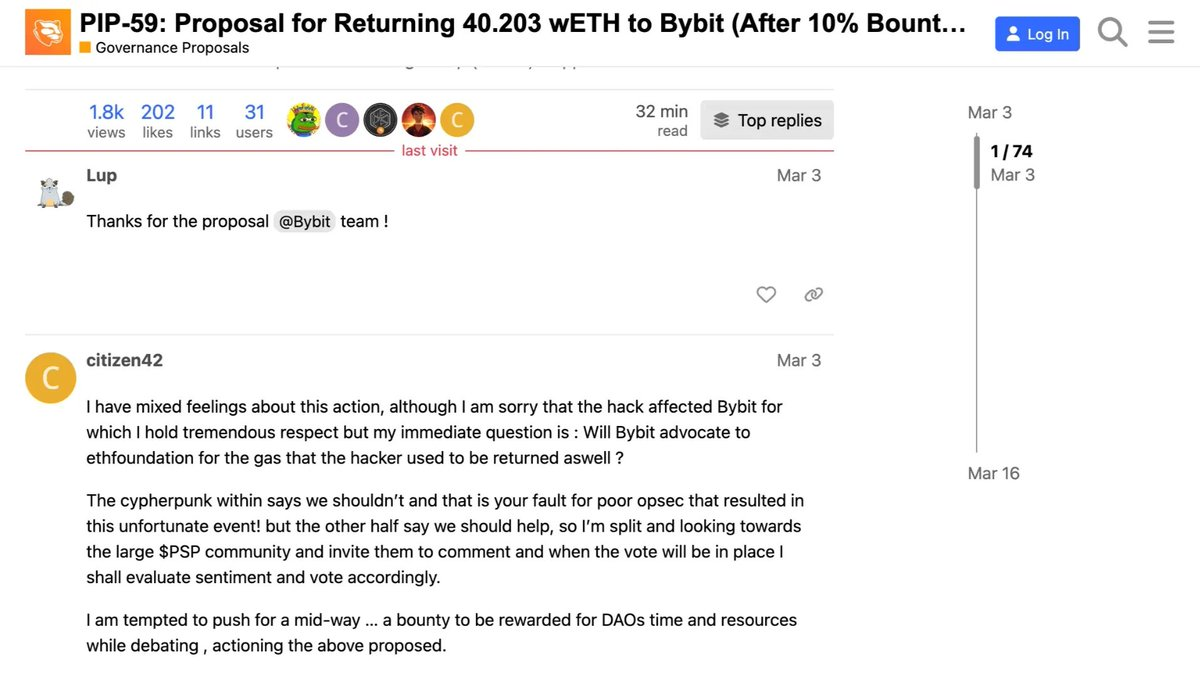

2/ The deep dilemma of DAO governance: Calling for consensus! Please respond if you hear this! Over!

Where does the problem lie? Some attribute the low voting rates simply to "voting being unprofitable," and thus propose a "vote-to-earn" model, using token rewards to stimulate voting (Mitsui, 2024).

However, this line of thinking has a fundamental flaw: the essence of voting is not "mining," but "consensus transmission." If the consensus transmission mechanism itself has already failed, any economic incentive is merely a superficial remedy.

Therefore, I believe that the core issue of DAO governance is not simply a "lack of consensus," but rather the systematic failure of the consensus transmission mechanism. In other words, users are not indifferent; they are blocked by fragmented participation processes, fragmented information, and high cognitive costs.

Theoretically, the governance dilemma of DAOs can be dissected from these three levels:

2.1 DAO: Can you give me a song's worth of time?

In today's information explosion, low DAO participation is often not due to member indifference, but because the governance process itself causes attention fragmentation—users' attention has long been divided by social media, financial pressures, and daily life.

@DeepDAO_io research shows, the governance ecology of DAOs presents a typical "multi-threaded" model:

94% of DAOs use the X platform for socializing and promotion;

41% use Medium to publish articles;

75% use Telegram or Discord for cross-group discussions, while only 9% engage in systematic governance dialogue through forums.

This means that most DAOs lack a true "information center," and governance information is scattered like fragments in different corners. If members want to participate seriously, they must jump back and forth between multiple platforms:

- Discovery: Accidentally catching proposal announcements in the information stream on X.

- Discussion: Jumping to Discord/Telegram or forums, struggling to piece together others' viewpoints in chaotic group chats.

- Decision-making: Opening the Snapshot website to connect a wallet and vote.

- Follow-up: Returning to X or the official website to check the final results.

This is akin to asking someone to simultaneously scroll through short videos, reply to WeChat messages, write reports, and take notes—it's a complete multitasking hell. This fragmented process brings enormous cognitive burdens and operational friction, as Nobel laureate Herbert Simon sharply stated: "Where information is rich, attention must be poor." Even if users are willing to participate, their attention is consumed in platform switching, ultimately leading to resignation.

Moreover, when DAO governance requires users to invest significant cognitive resources (such as studying complex proposals and verifying on-chain data), most users often find it too burdensome and choose shallow participation, blind following, or reliance on agents.

This precisely hits on the "rational ignorance" theory proposed by Eastbrook and Fisher: for ordinary token holders, spending a lot of time studying proposals before voting incurs costs far exceeding the benefits. Thus, they rationally "choose not to know," delegating governance power to professionals. This "separation of ownership and control" superficially appears to be an efficient adaptation, but in reality, it harbors centralization risks.

Over time, the fragmentation of attention inevitably leads to governance power skewing towards two types of people:

"Whale" large holders: willing to bear participation costs due to significant interests;

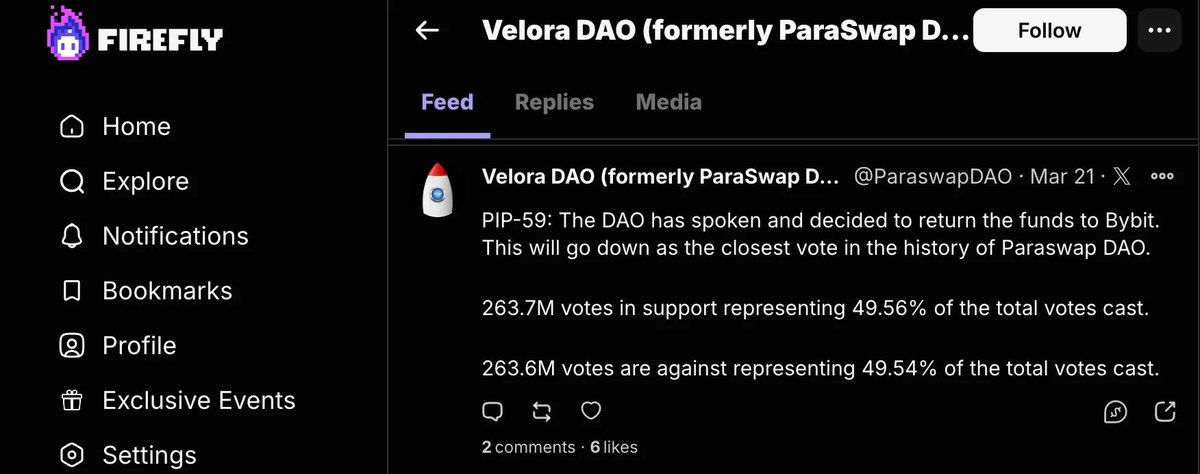

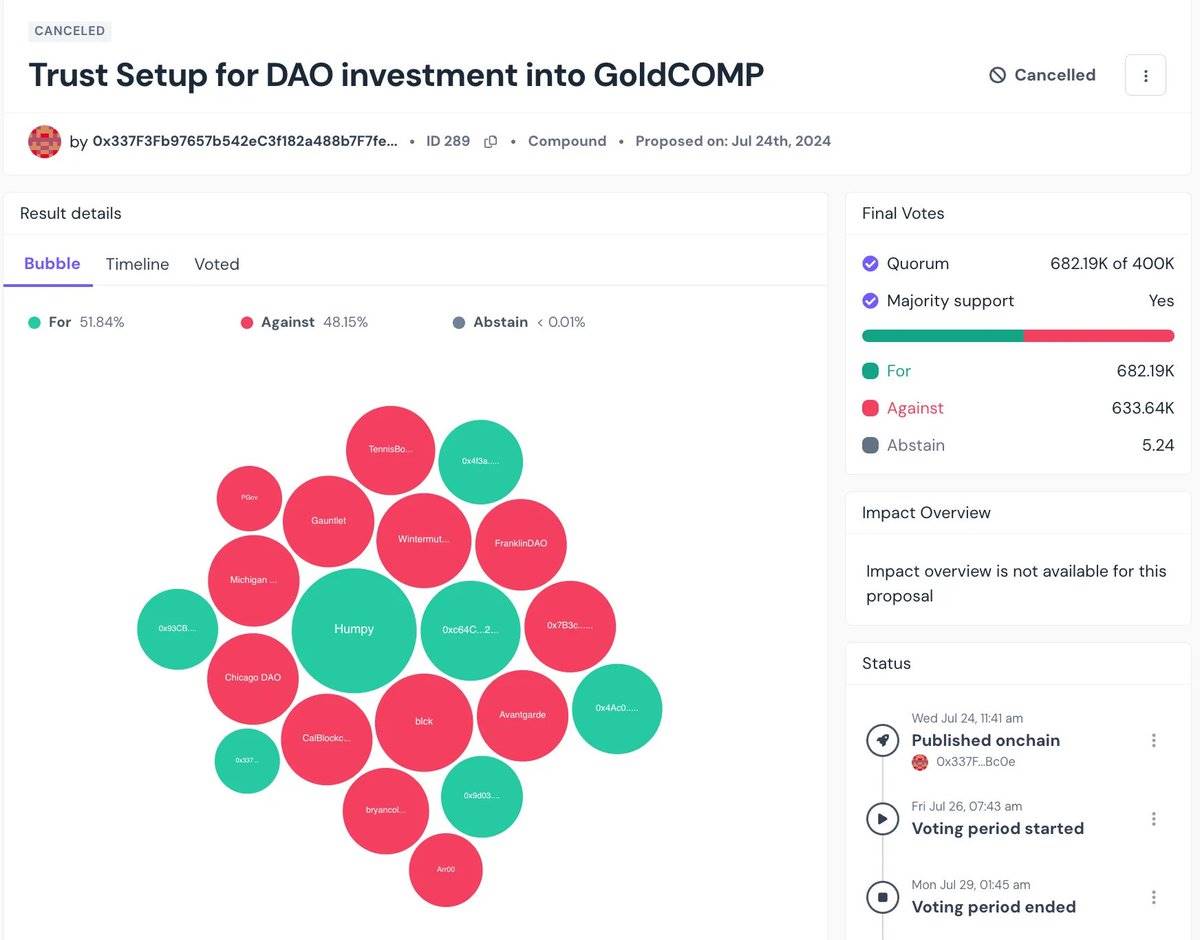

Governance professionals: treating participation in DAO governance as a job, even receiving salaries. The Compound Proposal-289 case is a cautionary example. Although Michael Lewellen from the Web3 security company OpenZeppelin publicly questioned the motives of "Golden Boys" and "Humpy," the latter still pushed the proposal through with a decisive voting power of 81%, passing it with a narrow margin of 51.84% to 48.16%, attempting to transfer nearly 500,000 COMP to his control address.

Data source: Tally

Although the proposal was ultimately checked, the entire process starkly illustrates that in a context of extreme scarcity of attention, major decisions in DAOs can easily be dominated by a few individuals. Even if the governance structure appears decentralized, there remains a significant risk of resource misallocation.

2.2 DAO voting is not just a simple click

Economist Ronald Coase once explained in his transaction cost theory: when coordination costs exceed potential benefits, rational individuals tend to withdraw. The reality of DAO governance precisely falls into this paradox.

On the surface, DAO voting seems to be "barrier-free"—everyone can participate. But the real barrier is not the rules, but the "trouble" itself, namely the super high transaction costs formed by process fragmentation and cognitive burdens. DAO governance requires members to reach consensus on public issues; however, from discovering proposals, participating in discussions, to completing votes, it often requires crossing multiple platforms, leading to the actual effectiveness of governance being significantly offset by high participation costs, falling into the transaction cost trap.

Ordinary users: "Forget it, it's too troublesome; my vote doesn't matter anyway." The direct consequence of this is the fulfillment of another scholar Mancur Olson's prophecy: in large groups, the marginal impact of individual efforts approaches zero, leading to a widespread "free-riding" mentality. Rational choice drives members to relinquish decision-making power, waiting for others to bear the costs while they enjoy the benefits. This directly results in large-scale DAOs where:

Whales and large holders: "What a great opportunity! If you all don't vote, my vote is even more valuable; I'll set the rules."

The so-called "consensus" is merely the result of discussions among a few large holders and "professional governance teams," cloaked in a veneer of democracy.

This structural flaw makes governance easily deviate from rationality, sliding into emotional manipulation and public opinion control. As

@bryancolligan pointed out in his article, very few people thoroughly check details or verify data during the proposal approval process, and the few voices raising reasonable doubts are often drowned out by the "consensus enthusiasm" of the community.

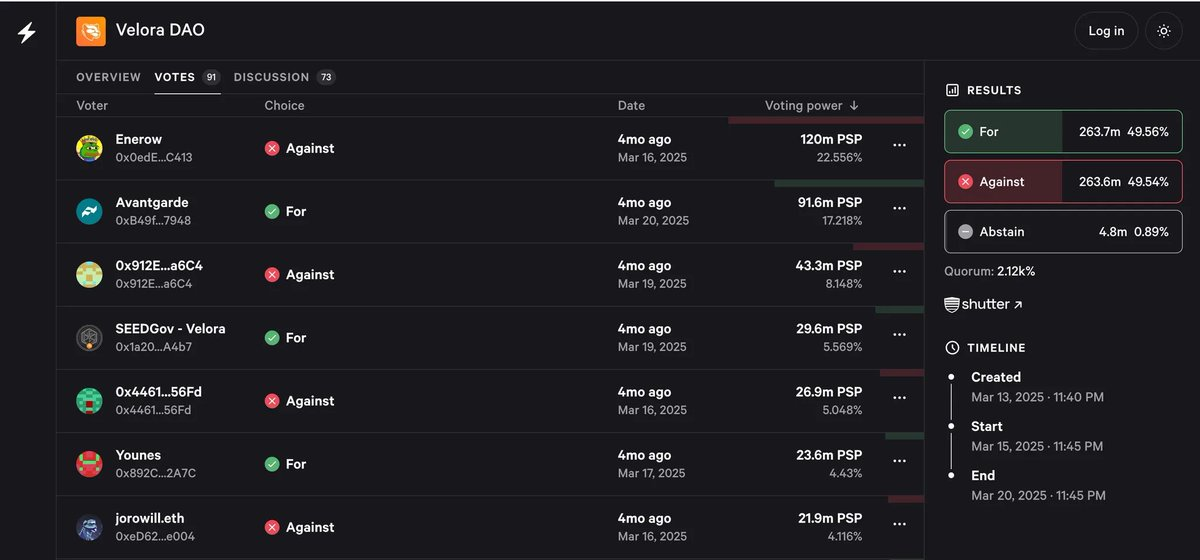

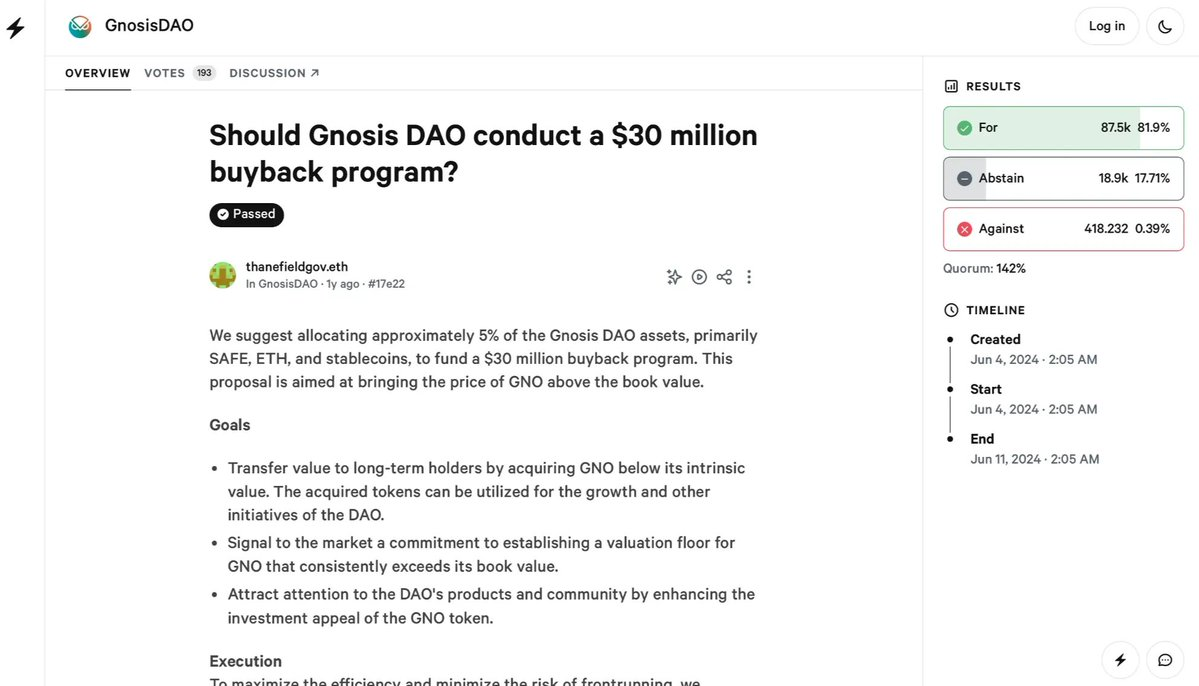

This is not an unfounded claim. The Gnosis DAO's GIP-128 proposal is a highly representative case that clearly reveals a reality—how to spend $30 million? 94 people decide.

The proposal planned to allocate $30 million to support the ecological construction of Gnosis Chain, Safe multi-signature wallets, and CoW protocol. Despite numerous doubts in the community forum—who manages the money? Is the project reliable? Is it overspending?—the proposal was still passed with 102% of the required voting number.

On the surface, this appears to reflect a high consensus within the community, but the data reveals another reality: among over 202,000 GNO holders, only 94 addresses participated in this vote.

Data source: Snapshot

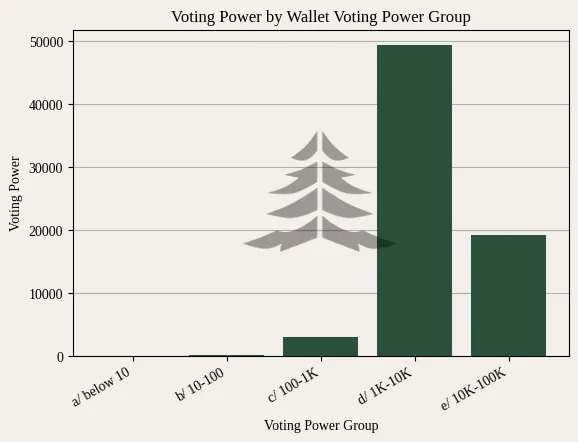

Among them, the top 4 wallet addresses by token quantity accounted for over 50% of the total voting power.

Data source: @PineGovBot

This is not a victory of community consensus, but a "oligarchic democracy" performance decided by less than 0.05% of the members, worth $30 million. More alarmingly, Gnosis's governance threshold (the required number of votes for approval) is set at 75,000 GNO—similar to most DAOs, intended to "lower participation barriers," but it inadvertently exacerbates the risk of concentrated voting power: just a few large holders can collaborate to determine the flow of tens of millions of dollars.

This "high consensus on the surface, but low participation in reality" situation is a direct consequence of high participation costs—most people find it troublesome and withdraw, ultimately forming a pseudo-consensus situation of "minority decision-making," giving rise to a type of "well-funded, low-participation" zombie DAO, severely deviating from the original intention of decentralized governance.

Therefore, the biggest enemy of DAO governance may not be malicious attackers or overly complex mechanism designs, but rather people's inherent "fear of trouble." When governance becomes a burden, democracy becomes a privilege for the wealthy and idle. We are only one phrase away from true decentralization: "Can we make this less troublesome?"

2.3 Power Re-concentration: I seem to see Yuan Shikai

When most members choose to withdraw from governance because participation is too troublesome, DAOs inevitably fall into an awkward situation where "a few people call the shots."

The academic research from Complutense University of Madrid clearly reveals this trend: the scale of DAOs is significantly positively correlated with power concentration—the larger the organization, the more members, the more concentrated the power.

- In most DAOs with over 1,000 voting members, more than 50% of the decision-making power is actually held by less than 1% of large holders.

This "superficial democracy, but actual centralization" model often further deforms in practice. As @bryancolligan revealed in his article, many proposals are internally finalized in Telegram groups, Discord channels, or even private chats before entering formal voting, making the so-called community voting merely a formality.

This leads DAOs to increasingly resemble "re-skinned companies" in practice: lacking transparency and unclear responsibilities, yet still claiming to be based on democratic consensus. This is not always a conspiracy; often, it is a necessity arising from systemic failure. To avoid the inefficiencies and risks of public governance, core participants turn to behind-the-scenes negotiations, resulting in a facade of transparency.

The "SLND1" case from Solend DAO in 2022 serves as a warning. To prevent a market crash that could be triggered by the liquidation of a certain whale account, the DAO initiated a proposal to take over that user's assets. On the surface, the proposal passed with an overwhelming advantage of 1.1 million votes in favor against 30,000 votes opposed. However, the truth is that over 1 million of the votes in favor came from a user with a massive governance token holding.

This incident sparked widespread criticism in the crypto community: is the DAO truly practicing the ideals of decentralization, or is it serving the interests of a few? Although Solend later voted to overturn the original proposal, this "illusion of decentralization" has severely eroded the DAO's public credibility at a critical moment.

3/ With Bitcoin at $100,000, why hasn't DAO broken through?

In recent years, many projects have attempted to optimize DAO governance, but they have generally failed due to one core issue: governance has not been integrated into users' daily behavior flows.

Mirror: Once achieved explosive growth through a content + DAO model, but ultimately weakened its core functionality, turning into an ordinary blog. Governance and content failed to integrate deeply.

Matters: Designed a comprehensive governance mechanism (applause rewards, citizen representative voting), but creators were more concerned about remuneration, leading governance to become a mere formality.

Paragraph: Attempted to build a "creator DAO" by acquiring Mirror and developing a Kiosk application based on Farcaster. However, its governance still adopted a "patchwork" approach, failing to integrate into social scenarios, making it difficult to reach mainstream users.

They collectively illustrate one thing: if governance cannot naturally grow into daily actions like liking or sharing, it will never escape the low participation dilemma.

So, what is the governance experience we are looking forward to?

Ideally, governance should:

Be as smooth as scrolling through short videos: come across a proposal → participate effortlessly → swipe to vote;

Not require switching apps, repeatedly checking information, or manual record-keeping.

Currently, there are indeed some attempts to lower voting barriers, such as using the Farcaster-based social application Warpcast and its frames feature to complete proposals and voting in one interface. This enhances operational smoothness and reduces participation friction—but it primarily optimizes the "click" without bridging the "consensus."

The real challenge has never been just "making voting easier," but rather how to ensure that each vote genuinely carries the user's attention and recognition.

Thus, DAO governance needs not monetary incentives or UI tweaks, but a reconstruction of behavioral pathways.

4/ The White Knight of DAO: Firefly, a one-stop solution for your governance actions

Firefly does not create a new platform but becomes a "governance behavior flow engine." It reconstructs not the functions, but the participation pathways—you no longer need to jump around; in one interface, you can see friends' updates, proposal votes, and content interactions, as simple as scrolling through a social feed!

Three key features to highlight:

- One wallet to rule them all: Using wallet addresses as a unified ID, automatically aggregating voting, transaction, and other records, allowing users to check and track governance dynamics anytime, eliminating the friction of switching between multiple platforms.

Video link: https://x.com/i/status/1958801901803511879

- Articles that speak: Content is directly linked to proposals, reading equals participation. Users can directly understand the proposal background and vote while browsing articles, without needing to switch to Snapshot.

Video link: https://x.com/i/status/1958801901803511879

- Follow friends into the DAO: Discover proposals through trusted friends or KOLs, gradually building a Web3 social totem, making governance no longer an isolated task but a natural extension of social interaction.

The core idea of Firefly is to change habits without altering the interface, making governance a natural action like scrolling through a feed. Users do not need to learn complex rules; they simply read updates and vote effortlessly.

This "habit reconstruction" transforms governance from an "extra task" into a daily behavior, significantly lowering participation barriers.

5/ Save the DAO! We need smart tools that can "work automatically!"

The bottleneck of DAOs has shifted from "fund management" to "consensus transformation." Future competition will not only be about asset scale but also about which community is more active—how many people can seamlessly integrate governance into their daily interactions?

Governance should not be an additional task for DAOs but a natural product of social interaction and collaboration. Only when voting, proposals, and discussions become as easy as liking or sharing will the silent majority truly come alive.

📲 Firefly reconstructs this layer of "behavioral infrastructure"—allowing governance to grow directly within social scenarios. Here, you are no longer a bystander in the DAO but a naturally flowing participant. Experience Firefly now and unlock the infinite possibilities of DAO governance!

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。