The boundaries of the transferability of computing power and security budgets are being re-examined.

Author: CoinW Research Institute

Recently, the AI public chain Qubic, driven by the "useful proof of work (uPoW)" mechanism, reorganized Monero blocks in a short period, resulting in 60 blocks being isolated. Although there is still controversy over whether this attack constitutes a strict 51% attack, its impact on the market has surpassed the technical level. The uncertainty of network integrity has forced exchanges to take risk control measures, and the price of Monero has also come under pressure. This attack event reveals that the security budget under the PoW mechanism may be penetrated under external incentives, exposing the structural vulnerabilities of computing power concentration and security boundaries.

More concerning is that the subsequent vote by the Qubic community listed Dogecoin, with a market value exceeding $35 billion, as a potential attack target. This trend not only deepens market concerns but also rekindles discussions about the relationship between incentive distribution of computing power and network integrity. The transferability of computing power and the boundaries of security budgets are being re-examined. In this context, the following analysis by CoinW Research Institute will delve deeper into this event.

1. Qubic's "51% Attack": Marketing Narrative or Technical Threat

1.1. How the uPoW Mechanism Breaks Traditional Security Budgets

In a standard PoW architecture, the cornerstone of computing power stability is the on-chain security budget, which is an incentive closed loop formed by block rewards and transaction fees. Taking Monero as an example, the network has currently entered a tail emission mode, with a fixed block reward of 0.6 XMR, producing a block approximately every two minutes, resulting in about 720 blocks mined daily, with a total security budget (approximately equal to miner block subsidies * XMR market price) of about $110,367 per day. This is also the economic lower limit that attackers must bear to continuously control the majority of computing power.

Qubic's introduction of useful proof of work (uPoW) breaks this traditional limitation. Unlike a model that solely relies on block rewards, Qubic provides miners with QUBIC block rewards while directing computing power towards Monero mining and converting this portion of rewards into USDT for repurchasing and destroying QUBIC on the open market. In this case, miners can not only directly obtain QUBIC block subsidies but also gain indirect benefits from the deflationary effect brought about by repurchase and destruction, resulting in a higher overall return than simply mining XMR. This allowed Qubic to rapidly mobilize a large amount of computing power in a short time, leading to the reorganization of six blocks and the abnormal phenomenon of nearly 60 isolated blocks. In fact, as early as June of this year, Qubic began mining Monero and Tari, converting all rewards into USDT for repurchasing QUBIC tokens and then destroying them. According to Qubic's official disclosure, this mining mechanism is over 50% more profitable than simply mining XMR and Tari.

Source: qubic.org

1.2. Doubts About the Credibility of Qubic's 51% Attack

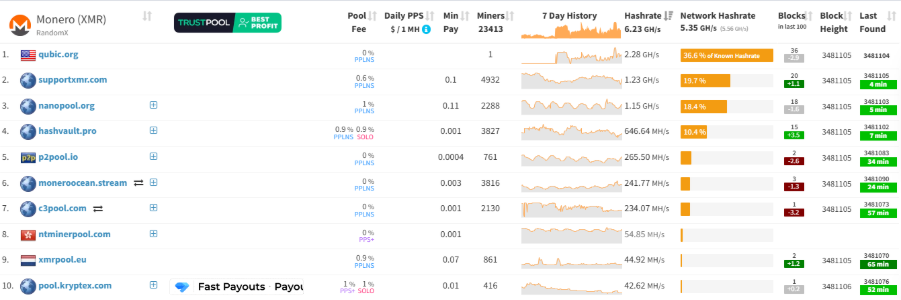

Although Qubic claims to have achieved a "51% attack" on Monero, this statement has been questioned by the community. According to publicly available data from the research institution RIAT, its peak computing power was only about 2.6 GH/s, while the total computing power of Monero during the same period was around 6.25 GH/s. In other words, Qubic's computing power accounted for less than 42%, which is significantly different from a true 51% attack. Further data supports this judgment; CoinWarz data shows that on the day of the incident, Monero's total network reached a peak of 6.77 GH/s, while MiningPoolStats recorded approximately 5.21 GH/s that day. This further indicates that Qubic's peak computing power was a momentary fluctuation, not a steady-state control. According to MiningPoolStats data, Qubic's mining pool currently has a computing power of about 2.16 GH/s, with a computing power share of 35.3%. The data discrepancies indicate instability in its control capability and a lack of sustained recognition.

Source: miningpoolstats

Despite the doubts about majority control, Monero's network security has not been materially affected, but Qubic's computing power disturbance has impacted the market in the short term. Kraken suspended XMR deposits due to network integrity risks, and upon resuming, raised the confirmation threshold to 720 blocks, reserving the right to suspend again. This indicates that even if it is not a true 51% attack, as long as there is a possibility of computational manipulation, the security chain of transactions will come under pressure in advance, challenging liquidity and confidence simultaneously.

2. Dogecoin Becomes the Next Potential Attack Target

2.1. Dogecoin as the Next Potential Target

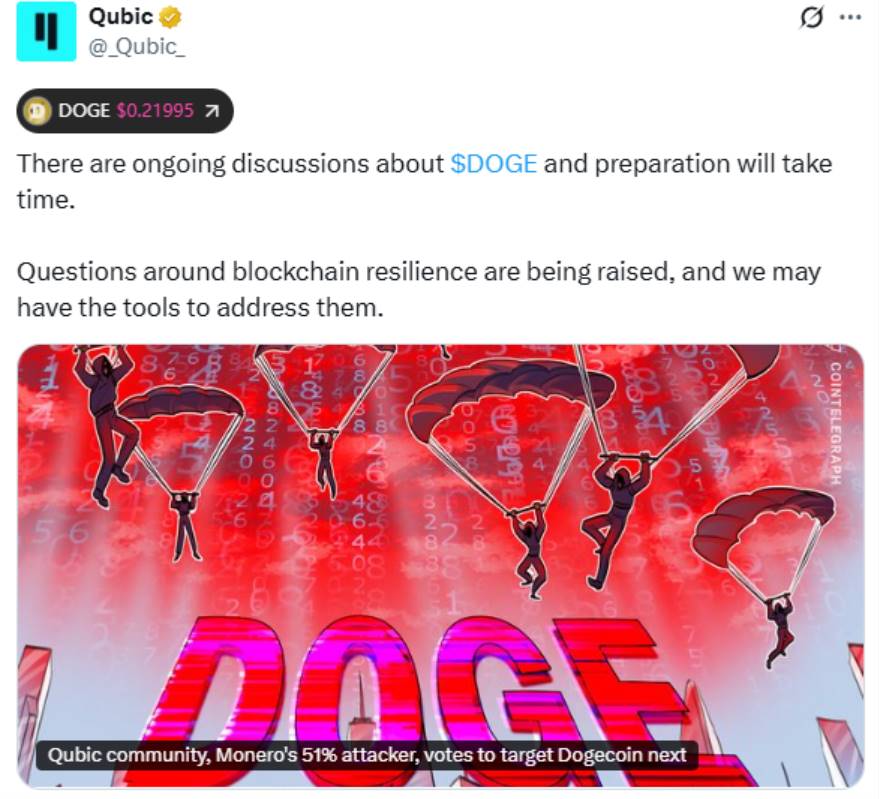

After Monero, Qubic has now identified Dogecoin as the next potential attack target. Recently, the Qubic community initiated a new vote to determine the next potential target for a 51% attack. The final results showed that Dogecoin received over 300 votes, significantly higher than candidates like Kaspa and Zcash. This vote has attracted market attention, indicating that Qubic's focus has shifted from the privacy coin Monero to a mainstream meme coin with a higher market value and broader user base.

The reason Qubic has garnered market attention is that it demonstrated a new economic incentive model during the Monero attack. This is not a traditional hacking behavior but rather a way to "rent" computing power through economic incentives, thereby reshaping the security assumptions of PoW. Currently, this model may be projected onto Dogecoin, amplifying market unease. Interestingly, after the vote, the Qubic community stated that they are mining Dogecoin rather than "attacking" it. From Qubic's official statements, the community generally interprets this event as a marketing maneuver rather than a purely technical attack.

Source: @Qubic

2.2. Can Qubic Attack Dogecoin?

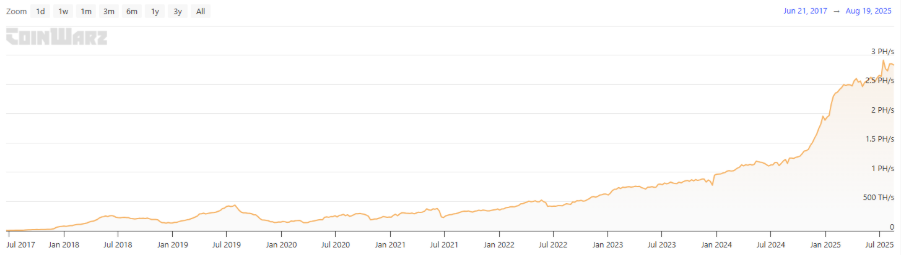

It is important to note that Qubic also adopted a method of mining first and then "attacking" Monero. Therefore, the community speculates that Qubic may also "attack" Dogecoin in the future. Can it be realized? To understand the risks, we need to first examine the scale of Dogecoin's computing power. According to CoinWarz data, the total computing power of Dogecoin is currently about 2.69 PH/s, with a historical peak of 7.68 PH/s, indicating the scale of miners' investment in hardware and electricity. According to the network mechanism, Dogecoin produces a block approximately every minute, with a fixed reward of 10,000 DOGE per block, resulting in a daily supply increase of about 14.4 million DOGE; at the current price of about $0.21, Dogecoin's daily security budget is approximately $3 million. In contrast, Monero, in the tail emission phase, adds only 432 XMR daily, corresponding to a security budget of about $110,000, far lower than Dogecoin. This gap indicates that under the same conditions, if Qubic attempts to launch a 51% attack on Dogecoin, the financial and technical barriers to attacking Dogecoin are much higher than those for Monero.

Source: coinwarz

Qubic's strategy is not to directly invest large sums of money but to attract temporary migration of computing power through a subsidy model. If a sufficient number of miners are incentivized by QUBIC to leave other chains and turn to Dogecoin in the short term, it may still impact block stability. Even if it cannot truly achieve a "double spend," it may lead to increased block delays and a higher rate of isolated blocks, thereby disrupting the normal operation of the network. It can also be understood that Qubic's attack does not necessarily have to be "successful"; creating chaos is enough to undermine market confidence.

3. The New Game of PoW Under AI Computing Power from the Qubic Incident

3.1. Miners' Liquidity and Loyalty Dilemma

The traditional PoW consensus relies on the logic that computing power equals security, meaning that the higher the computing power, the greater the cost of attacking the network, forming a solid moat. However, the Qubic incident has exposed a new reality: computing power is not locked in a single chain for the long term but is a resource that can be quickly transferred, rented, or even speculated. When computing power has high liquidity, its attributes resemble liquid capital in the capital market, ready to flow into areas with higher returns.

This liquidity of computing power directly changes the relationship between miners and the network. In the past, miners' incentives primarily came from block rewards and transaction fees, forming a long-term binding with the chain. However, under the Qubic model, the sources of miners' income have been redefined. This has led miners to gradually transform into computing power arbitrageurs rather than long-term guardians of a specific chain.

The more profound impact is that the security of PoW networks will no longer depend on the scale of computing power itself but rather on the stability of that computing power. Once computing power can be bought by higher bidders at any time, the cost of attacking the network is no longer a static absolute number but is highly correlated with fluctuations in the external market. As a result, PoW is no longer a solid security cornerstone but has become a temporary defense subject to external market dynamics, with security boundaries potentially being breached at any time.

3.2. The New Game of PoW in the Era of AI Computing Power

In the context of continuously rising demand for AI computing power, the security of PoW networks is being redefined. In the traditional model, computing power only circulates within the chain, and the security budget entirely relies on block rewards and transaction fees. However, the Qubic model has proven that computing power can also be directed outside the chain. For miners, computing power will naturally flow to the market that offers the highest returns. This means that the security budget of PoW is no longer a static cost within the chain but is linked to the global computing power market, and may even experience security flash crashes when AI computing power prices soar.

In this environment, PoW is likely just a transitional solution for AI public chains in the short term. Relying solely on PoW to maintain security is difficult to sustain in the long-term context of computing power outflow. In the future, more similar projects may shift to PoS or hybrid consensus mechanisms. Whether they can smoothly complete the migration of consensus mechanisms may become an important factor in assessing the long-term competitiveness of AI + PoW public chains.

At the same time, external security binding is becoming a more feasible path for the combination of PoW and AI public chains. For example, through a security leasing market, similar to EigenLayer's re-staking mechanism, the staking capital of Ethereum can be outsourced for use by AI public chains, providing them with a more stable and attack-resistant security budget. In this way, it no longer relies on its own computing power scale but hedges the risks of computing power liquidity by binding the long-term security of mature networks, which may become an important direction for AI public chains to break through the limitations of PoW.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。