Many types of wealth transfer, whether one-way or two-way, voluntary or forced, face the issue of transaction costs.

Written by: Nick Szabo

Translated by: Block unicorn

Summary

The precursors of money, along with language, helped early modern humans solve cooperation problems that other animals could not, including how to achieve mutual benefit, kin altruism, and reduce aggression. These monetary ancestors, like illegal tender, had very specific characteristics — they were certainly not just symbolic items or decorations.

Money

When England colonized America in the 17th century, it initially encountered a problem — a shortage of metallic currency [D94] [T01]. The British idea was to cultivate large amounts of tobacco in America, provide timber for their global navy and merchant fleet, and then exchange it for the supplies necessary to keep the American land productive. In reality, early colonists were expected to work for the company and also consume in the company’s stores. Investors and the British crown hoped for this, rather than paying farmers metallic currency to let them procure supplies independently and keep a little, well, the hellish profit.

There were other methods, right under the colonists' noses, but it took them years to discover this — the natives had their own currency, which was vastly different from the currency used by Europeans. Native Americans had been using currency for thousands of years, and it proved to be very useful to the newly arrived Europeans — except for those who held the bias that "money must bear the likeness of great figures." Worst of all, the natives in New England did not use gold or silver; they used the most suitable materials visible in their environment — the long-lasting parts of hunted animals' bones. Specifically, they made beads (wampum) from the shells of hard-shelled mollusks like venus mercenaria, strung into necklaces.

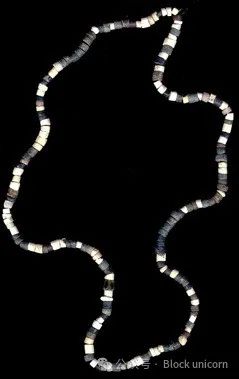

Beaded necklace. During transactions, people would point out the number of beads, take them out, and string them onto a new necklace. Native American beads were sometimes also strung into belts or other items of commemorative or ritual significance, indicating wealth or commitments to certain treaties.

These mollusks could only be found in the sea, but these beads were widely traded inland. Various types of shell currency could be found among the tribes of the American continent. The Iroquois never ventured to the mollusk habitats, yet the treasures of beads they collected were renowned among all tribes. Only a few tribes, like the Narragansett, were skilled in making beads, but hundreds of tribes (mostly hunter-gatherer tribes) used beads as currency. The lengths of beaded necklaces varied greatly, and the number of beads was proportional to the length of the necklace. Necklaces could always be cut or linked together to form lengths corresponding to the prices of goods.

Once the colonists overcame their doubts about the source of the value of currency, they began to trade beads wildly. Mollusks also became another expression of "money" in American vernacular. The Dutch governor of New Amsterdam (now known as "New York") borrowed a large sum of money from the English-American bank — the loan was in beads. Later, British authorities were forced to agree, so between 1637 and 1661, beads became a legal tender in New England, providing colonists with a highly liquid medium of exchange, which in turn prospered colonial trade.

However, as the British began to ship more metallic currency to America and Europeans started using their mass manufacturing techniques, shell currency gradually declined. By 1661, British authorities had surrendered, agreeing to pay with the kingdom's metallic currency — namely gold and silver, and that year, shell beads were abolished as legal tender in New England.

But in 1710, beads were again recognized as legal tender in North Carolina, and they continued to be used as a medium of exchange, even into the 20th century; however, due to Western harvesting and manufacturing techniques, the value of beads increased a hundredfold, and subsequently, with the advent of the metallic currency era, they followed the path of gold and silver jewelry in the West, gradually transforming from carefully crafted currency into decorative items. In American vernacular, shell currency also became a strange old term — after all, "100 shells" had turned into "100 dollars." "Shelling out" became a term for paying with metallic currency or bills, and now it has evolved into paying with checks or credit cards [D94]. (Translator's note: Shell means shell, and "shelling out" originally referred to paying with shells.)

We may not realize that this touches upon the origins of our species.

Collectibles

In addition to shells, currency on the American continent has taken many forms. Hair, teeth, and a multitude of other items have been widely used as mediums of exchange (we will discuss their common attributes later).

12,000 years ago, in what is now Washington State, the Clovis people crafted some astonishing long flint blades. The only problem was that these blades were too brittle — meaning they could not be used for cutting; these flint pieces were "made purely for entertainment," or for purposes entirely unrelated to cutting.

As we will see later, this apparent frivolity likely played a very important role in their survival.

Native Americans were not the first group to create beautiful yet useless flint artifacts, nor were they the first to invent shell currency; it is worth noting that Europeans were not either, although they had previously used shells and teeth extensively as currency — not to mention cattle, gold, silver, weapons, and other items. Asians used all these items, as well as government-issued fake axes (translator's note: likely referring to "knife coins"), but they also introduced this tool (shells). Archaeologists have discovered shell necklaces dating back to the early Paleolithic — easily interchangeable with the currency used by Native Americans.

Pea-sized beads made from the shell of the sea snail Nassarius kraussianus. These snails live at estuaries. Discovered in Blombos Cave, South Africa. Dated to 75,000 years ago.

In the late 1990s, archaeologist Stanley Ambrose discovered some necklaces made from ostrich eggshell and shell fragments hidden in a stone shelter in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya. Using (40Ar/42Ar) argon dating, the necklaces were dated to at least 40,000 years ago. Animal tooth beads found in Spain can also be traced back to this era. Perforated shells from the early Paleolithic have also been found in Lebanon. Recently, complete shells (prepared as beads) were discovered in South Africa's Blombos Cave, dating back to 75,000 years ago!

Ostrich eggshell beads, discovered in the East African Rift in Kenya. Dated to 40,000 years ago. (Thanks to Stanley Ambrose)

These modern human subspecies migrated to Europe, where shell necklaces and teeth appeared around 40,000 years ago. Shell and tooth necklaces appeared in Australia around 30,000 years ago. In all cases, the craftsmanship was highly skilled, suggesting that such practices could be traced back to even earlier periods revealed by archaeological work. The origins of collectibles and decorative items likely lie in Africa, the origin of anatomically modern humans. The collection and crafting of necklaces must have provided some extremely important survival advantages, as they were all luxurious — making these necklaces required considerable skill and time, while humans were still struggling on the brink of starvation.

Essentially, all human cultures, even those that did not engage in large-scale trade or use more modern forms of currency, created and appreciated jewelry and items whose artistic or heritage value far exceeded their practicality. We humans collect shell necklaces and other forms of jewelry — simply for pleasure. For evolutionary psychologists, the notion that "humans do something just for pleasure" is not an explanation but merely poses a question. Why do so many people find the luster of collectibles and jewelry pleasurable? More straightforwardly, the question is — what evolutionary advantage does this pleasure provide to humans?

A necklace found in a burial site in Sungir, Russia, dated to 28,000 years ago. It consists of interlocking and interchangeable beads. Each mammoth ivory bead may have taken one or two hours of labor to produce.

Evolution, Cooperation, and Collectibles

Evolutionary psychology stems from a key mathematical discovery by John Maynard Smith. Smith borrowed the population model of co-evolving genes (derived from the well-developed field of Population Genetics) to point out that genes can correspond to behavioral strategies, encoding good or bad strategies in simple strategic problems (i.e., "games" in the sense of game theory).

Smith demonstrated that competitive environments can be expressed as strategic problems, and these genes must prevail in competition to be passed on to subsequent generations, thus evolving Nash equilibria for the relevant strategic problems. These competitive games include the prisoner's dilemma (a classic cooperation game problem) and the hawk/dove strategy problem (a classic aggression strategy problem).

The key to Smith's theory is that these strategic games, while appearing to unfold in physical form, are fundamentally played out between genes — that is, in the competition for gene propagation. It is genes (rather than individuals) that influence behavior, exhibiting what seems to be bounded rationality (encoding the best possible strategies within the range expressible by biological forms, of course, biological forms are also influenced by biological raw materials and previous evolutionary history) and "selfishness" (borrowing Richard Dawkins' metaphor). The influence of genes on behavior is an adaptation to the competition that genes engage in through physical forms. Smith referred to these evolving Nash equilibria as "evolutionarily stable strategies."

The "classical theories" built on early individual selection theories, such as sexual selection and kin selection theories, have been dissolved into this more general model, which disruptively places genes rather than individuals at the center of evolutionary theory. Thus, Dawkins used a frequently misunderstood analogy — "the selfish gene" — to describe Smith's theory.

Few other species surpass even Paleolithic humans in terms of cooperation. In some cases, such as the hatching and colonization behaviors of species like ants, termites, and bees, animals can cooperate among kin — because this helps replicate the "selfish genes" they share with their relatives. In some very extreme situations, cooperation can also occur between non-relatives, which evolutionary psychologists refer to as "reciprocal altruism." As Dawkins describes, unless the transaction is simultaneous on both sides, one party in the transaction can cheat (sometimes even instantaneous transactions are difficult to avoid fraud). Moreover, if they can cheat, they usually will. This is the outcome that often arises in the game known as the "prisoner's dilemma" — if all parties cooperate, then each can achieve a better outcome, but if one party chooses to cheat, they can betray the other fool and profit. In a population composed of deceivers and fools, deceivers always win (making cooperation difficult). However, some animals achieve cooperation through repeated games and a strategy called "tit for tat": cooperating in the first round of the game, then always choosing to cooperate until the opponent chooses to cheat, at which point they choose to cheat to protect themselves. This threat of retaliation encourages both parties to continue cooperating.

Overall, instances of actual cooperation among individuals in the animal world are very limited. One major limitation of this cooperation lies in the relationship between the cooperating parties: at least one party is more or less forced to be close to the other participants. The most common scenario is the evolution of symbiosis between parasites and hosts. If the interests of the parasite and the host align, then symbiosis becomes more suitable than going their separate ways (i.e., the parasite also provides some benefits to the host); thus, if they successfully enter a tit-for-tat game, they will evolve into a symbiotic relationship, where their interests, especially the genetic exit mechanisms from one generation to the next, are aligned. They will become like a single organism. However, in reality, there is not only cooperation between the two but also exploitation, and both occur simultaneously. This situation is quite similar to another system developed by humans — tribute — which we will analyze later.

There are also some very special examples that do not involve parasites and hosts but share the same body and become symbiotic. These examples involve non-kin animals and very limited territorial space. A beautiful example cited by Dawkins is the cleaner fish, which swim in the mouths of their hosts, eating the bacteria and maintaining the health of the host fish. The host fish can deceive these cleaner fish — they can wait until the cleaner fish finish their work and then swallow them whole. But the host fish does not do this. Because both parties are constantly moving, either can freely leave this relationship. However, cleaner fish have evolved a very strong territorial sense, along with difficult-to-imitate stripes and dances — much like an unforgeable trademark. Therefore, the host fish knows where to find cleaning services — and they know that if they deceive the cleaner fish, they will have to seek out a new group of cleaner fish. The entry cost of this symbiotic relationship is very high (thus the exit cost is also high), so both parties can happily cooperate without fraud. Additionally, cleaner fish are very small, so the benefits of eating them do not outweigh the cleaning services provided by a small group of fish.

Another highly relevant example is the vampire bat. True to its name, this bat feeds on the blood of mammals. The interesting part is that whether they can successfully obtain blood is very unpredictable; sometimes they can feast, and other times there is nothing to eat. Therefore, lucky (or more experienced) bats will share their prey with those who are less fortunate (or clever): the giver will regurgitate blood, and the receiver will gratefully consume it.

In most cases, the giver and receiver are related. In the 110 such examples observed by the incredibly patient biologist G.S. Wilkinson, 77 involved mothers nursing their young, while most of the other examples involved genetic kinship. However, there are still a few examples that cannot be explained by kin altruism. To explain this portion of reciprocal altruism, Wilkinson mixed bats from two groups to form a population. He then observed that, with very few exceptions, bats generally only cared for their old friends from their original group.

This cooperation requires the establishment of long-term relationships, meaning partners must interact frequently, understand each other, and track each other's behavior. Caves help restrict bats to long-term relationships, making such cooperation possible.

We will also learn that some humans, like vampire bats, choose high-risk and unstable forms of harvest, and they share the surplus of production activities with those who are not related. In fact, their achievements in this regard far exceed those of vampire bats, and how they achieve these accomplishments is the subject of this article. Dawkins states, "Money is a formal token of delayed reciprocal altruism," but then he does not further advance this fascinating idea. This is the task of our article.

In small human groups, public reputation can replace retaliation from individual parties, driving people to achieve cooperation through delayed exchanges. However, reputation systems may encounter two significant problems — difficulty in confirming who did what and difficulty in assessing the value or damage caused by actions.

Remembering faces and the corresponding favors is a considerable cognitive hurdle, but it is also a barrier that most humans find relatively easy to overcome. Recognizing faces is relatively easy, but recalling a past instance of help when needed may be more difficult. Remembering the details of a favor that brought a certain value to the recipient is even harder. Avoiding disputes and misunderstandings is impossible, or it can be difficult enough to prevent such help from occurring.

The assessment problem, or the issue of valuing, is very widespread. For humans, this problem exists in any transaction system — whether it is social exchanges, barter, currency, credit, employment, or market transactions. In extortion, taxation, tribute, and even judicial punishment, this problem is also significant. Even in animal reciprocal altruism, this issue is particularly important. Imagine mutual help among monkeys — for example, exchanging a piece of fruit for a back scratch. Grooming each other can remove lice and fleas that one cannot see or reach. However, how many grooming sessions correspond to how many pieces of fruit to make both parties feel "fair" rather than being taken advantage of? Is 20 minutes of grooming worth one piece or two pieces of fruit? How big is a piece?

Even the simplest "blood for blood" transaction is more complex than it appears. How do bats estimate the value of the blood they receive? Based on weight, volume, taste, and satiety? Or other factors? This complexity in measurement exists equally in the monkeys' "you scratch my back, I scratch yours" transactions.

Although there are many potential trading opportunities, animals struggle to solve the problem of valuing. Even in the simplest pattern of remembering faces and matching them with a history of favors, achieving a sufficiently precise consensus on the value of favors at the outset is a significant barrier for animals to develop reciprocal altruism.

However, the stone toolkits left behind by Paleolithic humans seem a bit too complex for our brains. (Translator's note: This means that if it is so complex for the modern human brain, what kind of cooperative forms did Paleolithic humans use to create these tools, and what were they for?)

Tracking favors related to these stones — who made what quality of tools for whom, and who owes whom what, etc. — can become very complicated, especially if it crosses tribal boundaries. Additionally, there may be a large number of organic materials and ephemeral services (like grooming) that do not leave a trace. Even just remembering a small portion of these traded items and services in one's mind, as the quantity increases, makes it increasingly difficult to match people with events until it becomes impossible. If cooperation also occurred between tribes, as archaeological records suggest, then the problem becomes even more challenging, as hunter-gatherer tribes are often highly hostile and distrustful of one another.

If shells can be currency, furs can be currency, gold can be currency, etc. — if currency is not just coins and notes issued by governments under legal tender laws, but can be many different things — then what is the essence of currency?

Moreover, why do humans, who often live on the brink of hunger, spend so much time creating and appreciating those necklaces, when they could use that time to hunt and gather?

19th-century economist Carl Menger was the first to describe how money naturally evolves and emerges inexorably from a multitude of barter transactions. The story told by modern economics is similar to Menger's version.

Barter requires a coincidence of interests between the two parties involved in the transaction. Alice grows some walnuts and needs some apples; Bob happens to grow apples and wants walnuts. Moreover, they happen to live close to each other, and Alice trusts Bob, willing to wait quietly between the walnut harvest and the apple harvest. Assuming all these conditions are met, there is no problem with barter. But if Alice grows oranges, even if Bob also wants oranges, it won't work — oranges and apples cannot grow in the same climate. If Alice and Bob do not trust each other and cannot find a third party to mediate or enforce contracts, then their wishes will go unfulfilled.

There may also be more complex situations. Alice and Bob cannot fully redeem their promises to sell walnuts or apples in the future because there are other possibilities; Alice might keep the best walnuts for herself and sell the inferior ones to Bob (Bob can do the same). Comparing quality and comparing the qualities of two different items is even more difficult than the aforementioned issues, especially when one of the items has already become a memory. Additionally, neither can predict events like a poor harvest. These complexities greatly increase the difficulty of the problems Alice and Bob face, making it harder for them to confirm that delayed reciprocal exchanges can truly achieve reciprocity. The longer the time interval between the initial transaction and the return transaction, and the greater the uncertainty, the greater the complexity.

Another related issue (which engineers may realize) is that barter "doesn't scale." When the quantity of goods is small, barter can work, but its costs will gradually increase with the volume until it becomes too expensive to justify such exchanges. Assuming there are N types of goods and services, a barter market would require N² prices. Five goods would yield 25 relative prices, which is manageable; but 500 goods would result in 250,000 prices, far exceeding an individual's ability to track prices. With money, only N prices are needed — 500 goods mean 500 prices. In this scenario, money serves as both a medium of exchange and a standard of value — as long as the price of the money itself is not too high to remember or fluctuates too frequently. (The latter issue, combined with implicit insurance "contracts" and a lack of competitive markets, may explain why prices are often evolved over the long term rather than determined by recent negotiations.)

In other words, barter requires a coincidence of supply (or skills), preferences, time, and low transaction costs. The growth of transaction costs in this model will far exceed the growth of the variety of goods. Barter is certainly better than no trade at all and has been widely practiced. But compared to trade using money, it is still quite limited.

Before the emergence of large-scale trade networks, primitive currency existed for a long time. Currency had an even more important use prior to this. By significantly reducing the demand for credit, currency greatly improved the efficiency of small barter networks. The complete coincidence of preferences is much less than the intertemporal coincidence of preferences. With currency, Alice can gather blueberries for Bob when they ripen this month, while Bob can hunt large animals for Alice six months later, without needing to remember who owes whom what, nor needing to trust each other's memory and integrity. A mother's significant investment in child-rearing can be protected by gifting irreplaceable valuable items. Moreover, currency transforms the problem of labor division from a prisoner's dilemma into simple exchanges.

The primitive currency used by hunter-gatherer tribes looks vastly different from modern currency and plays a different role in modern culture; primitive currency may have some functions limited to small trading networks and local institutions (which we will discuss later). Therefore, I believe it is more appropriate to refer to them as "collectibles" rather than "currency." In the anthropological literature, such items are also referred to as "currency"; this definition is broader than government-issued paper money and metal currency but narrower than the "collectibles" or the more vague "valuable items" used in this article (the latter refers to things that are not collectibles in the sense of this article).

The reason for choosing "collectibles" over other terms to refer to primitive currency will gradually become apparent in the following text. Collectibles have very specific attributes and are certainly not just decorative. While the specific items collected and their valuable attributes vary across cultures, they are by no means arbitrarily selected. The primary function of collectibles, and their ultimate function in evolution, is to serve as a medium for storing and transferring wealth. Some types of collectibles, such as necklaces, are very suitable for use as currency, and even we (living in a modern society that encourages trade) can understand this. I occasionally use "primitive currency" as a substitute for "collectibles" when discussing wealth transfer before the era of metal currency.

The Gains from Trade

Individuals, clans, and tribes engage in trade voluntarily because both parties believe they will gain. Their value judgments may change after the trade, as they gain experience with goods and services through trading (thus altering their standards of judgment). However, at the time of the transaction, their value judgments may not accurately correspond to the value of the traded items, but they are generally correct in judging whether the trade is beneficial. Especially in early inter-tribal trade, since the traded items are limited to high-value goods, all parties have a strong incentive to make their judgments accurate. Therefore, trade almost always benefits all parties involved. In terms of value creation, trade activities are no less significant than physical activities like production and manufacturing.

Because the preferences of individuals, clans, and tribes differ, and their ability to satisfy their preferences, as well as their awareness of their skills and preferences and their outcomes, also vary, they are always able to gain from trade. Whether the costs required to engage in trade — that is, transaction costs — are low enough to make these trades worthwhile is another question. In our era, there is much more trade that can occur than in most previous eras. However, we will discuss later that certain types of trade have always been worth the transaction costs, and for some cultures, such trades can even be traced back to the early stages of Homo sapiens.

It is not only voluntary spot trades that can benefit from lower transaction costs. This is crucial for understanding the origins and evolution of currency. Family heirlooms can be used as collateral, eliminating the credit risk of delayed exchanges. The ability to collect tribute from defeated tribes is a significant advantage for the victorious tribe; this ability, like trade, can also benefit from the same transaction cost technologies; arbitrators assessing the actual damage caused by violations of customs and laws, as well as kin groups arranging marriages, are examples of this. When receiving an inheritance, if there is wealth that can withstand the passage of time and does not rely on others, kin will undoubtedly benefit more (Kin also benefited from timely and peaceful gifts of wealth by inheritance). The main activities of humans living isolated from the commercial world in modern culture derive benefits from technologies that reduce transaction costs that are no less than those gained from trading activities, and perhaps even more. Among these technologies, none is more efficient, more important, or appeared earlier than primitive currency — collectibles.

After Homo sapiens replaced Neanderthals (H. sapiens neanderthalis), the human population subsequently surged. Artifacts from Europe, dating back 35,000 to 40,000 years, show that Homo sapiens increased the environmental carrying capacity by tenfold compared to Neanderthals — that is, a tenfold increase in population density. Moreover, the newcomers had time to create the world's earliest art — such as beautiful cave paintings, diverse exquisite sculptures — and of course, necklaces made from shells, teeth, and eggshells.

These objects are not useless decorations. The new and efficient means of wealth transfer were brought about by these collectibles, along with possibly more advanced progress and language; the new cultural tools created in this way may have played an important role in enhancing environmental carrying capacity.

As newcomers, Homo sapiens had brain capacities comparable to Neanderthals, softer bones, and less robust muscles. Their hunting tools were more sophisticated, but 35,000 years ago, the tools were basically similar — not even twice as efficient, let alone ten times. The biggest difference may lie in the wealth transfer tools created and enhanced by collectibles. Homo sapiens derived pleasure from collecting shells and using them to create jewelry, display jewelry, and trade with one another. Neanderthals did not. Perhaps it was this same mechanism that allowed Homo sapiens to survive in the whirlpool of human evolution tens of thousands of years ago and emerge on the Serengeti plains of Africa.

We should discuss how collectibles reduce transaction costs by type — from voluntary free gifts, to voluntary mutual trade and marriage, to involuntary judicial rulings and tribute.

All types of value transfer have appeared in many prehistoric cultures and may trace back to the early stages of Homo sapiens. The benefits gained by one or more parties from the wealth transfer of significant life events can be large enough to ignore high transaction costs. Compared to modern currency, the circulation speed of primitive currency is very low — in an ordinary person's lifetime, it may only change hands a few times. However, a collectible that can be preserved for a long time, what we today call a "heirloom," can remain intact for generations and increase in value with each transfer — often making transactions that would not have occurred possible. Tribes thus spend a lot of time on seemingly meaningless manufacturing work and exploring new materials that can be used.

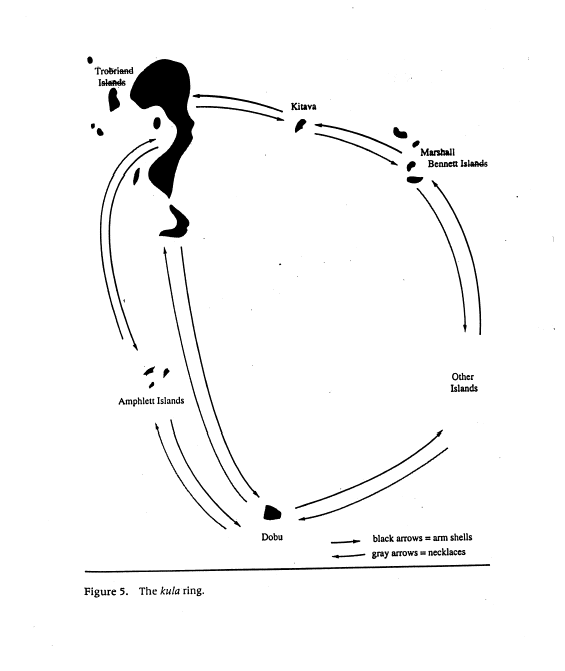

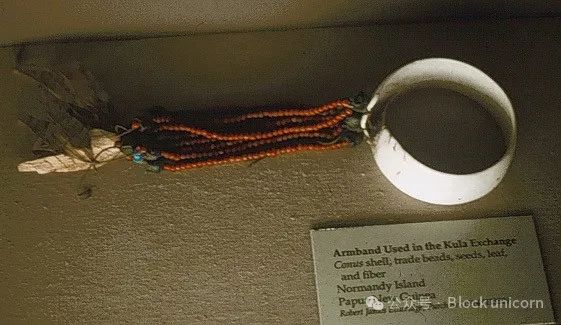

The Kula Ring

In pre-colonial times, the Kula trade network on the Melanesian islands. Kula is both a "very powerful" currency and a monument of stories and legends. The goods that can be traded (mostly agricultural products) are distributed across different seasons, making barter impractical. Kula collectibles have irreplaceable valuable worth and can be worn and circulated; as a form of currency, it solves the double coincidence of wants problem. Because it can solve this problem, a bracelet or a necklace can gain a value higher than its manufacturing cost after a few trades and can continue to circulate for decades. The legends and stories about the previous owner of the collectible further provide information about upstream credit and liquidity. In Neolithic cultures, the forms of circulating collectibles (usually shells) are often more irregular, but their purposes and attributes are similar.

Kula ring (mwali)

Kula necklace (bagi)

For any tool whose primary function is to transfer wealth, we can ask the following questions:

Do the two events (i.e., the production of the traded items and their application) need to meet some coincidence in terms of time interval? How much of an obstacle does the impossibility of coincidence pose to wealth transfer?

Can the transfer of wealth be based solely on the formation of a collectible cycle with that tool, or must other tools be involved to form a complete cycle? A serious study of the actual picture of currency circulation is crucial for understanding the birth of currency. For most of human prehistory, there was no currency circulation covering a large number of different trades, nor could there be. Without a complete and repeated cycle, collectibles cannot circulate and will lose their value. A collectible must be able to mediate enough transactions to amortize its manufacturing cost, making it worthwhile to produce.

Let us first examine the type of wealth transfer we are most familiar with today, which is also the most economically significant — trade.

Hunger Insurance

Bruce Winterhalder observed occasional patterns of food transfer among animals: tolerated theft, production/ begging/ opportunism, risk-sensitive survival conditions, reciprocal altruism as a byproduct, delayed reciprocity, non-spot exchanges, and other patterns (including kin altruism). Here, we will only look at risk-sensitive survival conditions, delayed reciprocity, and non-spot trading. We argue that using food-collectibles for mutual exchange can replace delayed reciprocity, enhancing the degree of food sharing. This approach can reduce the risks posed by fluctuating food supplies while avoiding most of the problems that the delayed reciprocity model cannot overcome between groups. We will address kin altruism and the issue of theft (whether forgiven or not) in a broader context later.

The value of food to the hungry is greater than its value to the sated. If a desperate person facing famine can use their most valuable possession to save their life, then the months of labor spent on that treasure is certainly worth it. People generally consider their lives to be more valuable than that heirloom. Thus, collectibles serve as a form of insurance against food shortages, much like fat. Local food shortages causing famine can be remedied in at least two ways — through food itself and the rights to forage and hunt.

However, transaction costs are generally too high — warfare is more common between groups than mutual trust. Groups unable to find food often go hungry. However, if transaction costs can be lowered by reducing the need for mutual trust between groups, food worth a day's labor for one group may be worth several months of labor for a starving tribe (and they can trade with each other).

As mentioned in this article, the most valuable trades that can be realized on a small scale emerged during the Upper Paleolithic period with the advent of collectibles in many cultures. Collectibles replaced the long-term mutual trust relationships that would otherwise have to exist (but in reality do not). If there were already long-term interactions and mutual trust between individuals of different tribes, the issuance of credit among them would not require guarantees, which would greatly stimulate intertemporal barter. However, such high levels of mutual trust are unimaginable — precisely because of the issues related to the reciprocal altruism model mentioned above, and these theories have been confirmed by empirical evidence: most of the relationships we observe among hunter-gatherer tribes are very tense. For most of the year, hunter-gatherer tribes would disperse into small groups, occasionally aggregating into "aggregates," much like medieval gatherings, for only a few weeks a year. Although there is no trust between groups, significant product trades, like the type illustrated, almost certainly occurred in Europe and in nearly all places, such as large game hunting tribes in the Americas and Africa.

The scenario illustrated is entirely theoretical, but if the reality were otherwise, it would be quite surprising. While many prehistoric Europeans enjoyed wearing shell necklaces, many humans living in more inland areas would use their teeth instead of shells to make necklaces. Flint, axes, furs, and other collectibles were also very likely used as mediums of exchange.

Reindeer, bison, and other game migrate at different times of the year. Different tribes excel at hunting different game, and in the remains from Upper Paleolithic Europe, over 90% or even 99% of the remains come from the same species. This situation suggests the existence of seasonal specialization within at least one tribe, or even a complete specialization of one tribe corresponding to one type of game. To achieve such a degree of specialization, members of a single tribe would have to become experts in the behavior, migration habits, and other behavioral patterns of that game, as well as understand the specialized tools and techniques used to hunt it. Some tribes we observe in modern times do have specialization. Some North American Indian tribes specialize in hunting bison and antelope, and also catch salmon. In parts of northern Russia and Finland, many tribes, including the Lapps, even to this day, only herd one type of reindeer.

Large wild animals that are not afraid of humans no longer exist. In the Paleolithic era, they were either driven to extinction or learned to fear humans and their projectile weapons (referring here to bows and arrows). However, for most of the time during the era of Homo sapiens, there were still many wild animal populations, and specialized hunters could easily catch them. According to our trade-survival theory, the degree of specialization in the Paleolithic era was likely higher because many large game animals (horses, bison, moose, reindeer, giant sloths, mastodons, mammoths, zebras, elephants, hippos, giraffes, musk oxen, etc.) roamed in herds across North America, Europe, and Africa. This inter-tribal hunting specialization also aligns with archaeological evidence from Upper Paleolithic Europe (though it cannot yet be said to be reliably proven).

These migrating groups, following the game, often interacted between groups, creating many trading opportunities. Native Americans preserved food by drying and making jerky, an activity that would last for several months but generally not for an entire year. This food would be exchanged for leather, weapons, and collectibles. Generally, these trades occurred during annual trading events.

Migratory herds of animals only pass through a territory twice a year, often with intervals of one to two months in between; without other sources of protein, these specialized tribes would starve. Only trade can make the high degree of specialization reflected in archaeological evidence possible. Therefore, even if only seasonal meat exchanges can be realized, collectibles are still worth using.

Those necklaces, flint, and other items used as currency circulate in a closed loop; as long as the quantity of meat traded is roughly equivalent, the quantity of collectibles used for trade is also roughly equivalent. Note that if the collectible circulation theory constructed in this article is correct, then one-way beneficial trade is not enough. We must identify a closed loop of mutually beneficial trade, in which collectibles continuously circulate and dilute their manufacturing costs.

As mentioned above, we know from archaeological evidence that many tribes specialize in hunting a single large animal. This means that hunters at least hunt different animals seasonally (seasonal specialization within the tribe); if extensive trade exists, it is also possible that a tribe only hunts one type of game throughout the year (complete specialization between tribes). While becoming an expert in animal behavior and mastering the best hunting methods can yield significant production benefits for a tribe, such benefits cannot be realized if they are left empty-handed for most of the year.

If trade is only realized between two complementary tribes, the total food supply may be nearly double. However, on the Serengeti plains and the European steppes, there are often more than a dozen species of animals (rather than just two) passing through. Therefore, for a specialized tribe, the amount of meat available can exceed double due to trade. More importantly, the additional meat will appear when people need it.

Thus, even the simplest trading loop composed of two types of game and two different but mutually compensating transactions can provide participants with at least four sources of benefits (or "surplus"):

Eating meat during seasons when they would otherwise go hungry;

An increase in the total supply of meat — they can sell the meat they cannot eat or store at the moment; after all, without trade, it would just go to waste;

The ability to eat different types of meat, leading to improved nutritional diversity;

Higher productivity gained from the specialization of hunting.

Creating or preserving collectibles for food exchange is not the only insurance measure against hunger seasons. Perhaps more common (especially in areas where large animals cannot be hunted) are transferable hunting rights on the territory. This can be observed in many of today's remaining hunter-gatherer cultures.

The !Kung San people of southern Africa, like all remaining hunter-gatherer cultures today, live on the margins. They do not have the opportunity to become professional hunters and must make use of the scarce resources available. They may therefore be less like ancient hunter-gatherer cultures and less like primitive Homo sapiens (who took the most fertile lands and best hunting routes from Neanderthals and only later completely drove Neanderthals out of the marginal areas). However, despite living in a harsh natural environment, the !Kung also use collectibles for trade.

Like most hunter-gatherer cultures, the !Kung people spend most of the year in small, dispersed groups, only gathering with a few other groups for a few weeks. These gatherings function like markets with additional functions — facilitating trade, consolidating alliances, strengthening partnerships, and arranging marriages. The preparation for these gatherings involves creating tradable items, some of which are practical, but most are of a collectible nature. This trading system, called !Kung hxaro, involves the trade of a large number of decorative jewelry items, including ostrich egg shell necklaces; these collectibles are very similar to those from Africa 40,000 years ago.

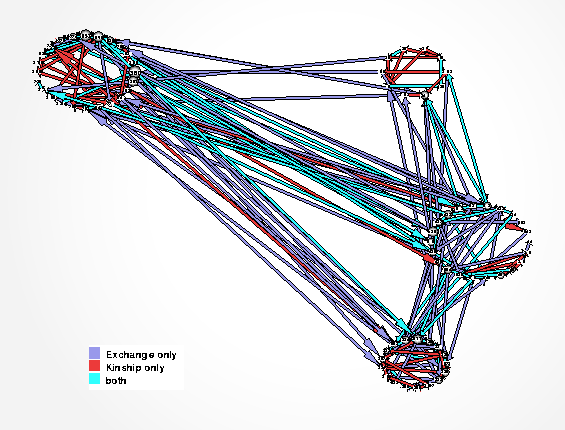

The model of hxaro trading and kinship among the neighboring tribes of the !Kung

Necklaces used for hxaro trading

One major item that the !Kung trade with collectibles is the abstract right to enter the territories of other groups (and forage and hunt). This trade is particularly active when local food is scarce, as it can alleviate hunger by foraging on neighbors' territories. The !Kung mark their group's territory with arrowheads; entering without purchasing the right to access and forage is akin to declaring war. Just like food trade between groups, purchasing foraging rights with collectibles is also a form of "insurance against hunger" (to borrow the words of Stanley Ambrose).

While anatomically modern humans can consciously think, speak, and possess a certain degree of planning ability, the emergence of trade requires almost no sophisticated thinking or language skills, and the portion that requires planning ability is even less. This is because tribe members do not need to infer other benefits beyond trade. To create such tools, it is sufficient for people to follow an instinct to pursue items with certain attributes (as we see in the indirect observations of accurately assessing these attributes). This applies to varying degrees to other institutions we need to understand — they evolved rather than being consciously designed. No one involved would explain the function of these institutions from an evolutionary perspective; instead, they would use many different myths to explain these behaviors, and the myths serve more as direct incentives for these behaviors rather than theories about their origins and ultimate purposes.

Direct evidence of food trade has long since vanished from history, but we may discover more direct evidence in the future by comparing the hunting patterns of one tribe with the consumption patterns of another among existing hunting tribes — the most challenging part may be identifying the boundaries of different tribes or kin groups. According to our theory, such inter-tribal meat exchanges should have been widespread in most areas during the Paleolithic era, when large-scale specialized hunting activities emerged.

Now, we have additional indirect evidence, which is the transfer of the collectibles themselves. Fortunately, the long-term retention attributes required for an object to become a collectible are the same as those that allow artifacts to survive to be discovered by archaeologists today.

The mainstream relationship between tribes is one of mutual distrust in good times and violence in bad times. Only marital or kin relationships can foster mutual trust between different tribes, albeit only occasionally and within limited scopes. Although collectibles can be worn or hidden in carefully concealed cellars, their fragile property protection means that collectibles must amortize their manufacturing costs within just a few transactions. Therefore, trade cannot be the only form of wealth transfer; in the long prehistory of humanity, it may not even be the primary one, as transaction costs were too high to develop markets, enterprises, and other economic systems we take for granted today. Beneath our great economic systems lie older systems that also involve wealth transfer. All these systems have allowed Homo sapiens to stand out among all animals. We now turn to one of the most fundamental forms of wealth transfer — a form that humans take for granted but animals seem to lack — inheritance.

Kin Altruism Across Death

The coincidence of supply and demand in time and space is extremely rare, so rare that most types of trade and trade-based economic systems we take for granted today could not exist. It is even less likely to find a triple coincidence that can meet the needs of supply and kin groups during significant events (such as the establishment of new families, death, crime, victory, or defeat). Therefore, we see that clans and individuals benefit greatly from timely wealth transfers during these events. Moreover, such wealth transfers waste less because they only involve the transfer of value of long-lasting wealth storage items, rather than consumer goods or tools for other purposes. The need for durable and universal wealth storage items in these systems is often more urgent than the need for trading media in trade. Furthermore, marriage arrangements, inheritance, dispute mediation, and tribute may have emerged even earlier than inter-tribal trade and involve more wealth transfer than trade does. Thus, these systems more powerfully facilitated the emergence of primitive currency compared to trade.

In most hunter-gatherer tribes, the forms of wealth transfer may seem trivial to us modern people who are "rolling in wealth": a set of wooden utensils, flint and bone tools, weapons, shell strings, or even a hat, or in colder climates, perhaps some moss-covered furs. Sometimes all these items are things that can be worn. These diverse items constitute the wealth of hunter-gatherers, akin to our real estate, stocks, and bonds. For hunter-gatherers, tools and warm clothing are essential for survival. Many items in wealth transfer are highly valuable collectibles that can be used to combat hunger, purchase partners, and can even save lives in times of war and defeat.

The ability to transfer survival capital to descendants is another advantage of Homo sapiens over other animals. Furthermore, skilled tribe members or clans can exchange surplus consumer goods for durable wealth (especially collectibles), and such trades can only occur occasionally, but they can accumulate throughout their lives. A temporary adaptive advantage is thus transformed into a lasting adaptive advantage for future generations.

Another form of wealth (which cannot be excavated by archaeologists) is social status. In many hunter-gatherer tribes, social status is often more valuable than tangible wealth. Such social status includes tribal leaders, military chiefs, hunting team leaders, members of long-term trade partnerships with other tribes, midwives, and religious leaders. Typically, collectibles not only represent wealth but also serve as symbols of tribal responsibility and status. When a person of status dies, to maintain order, a successor must be quickly and clearly designated. Delays may breed malicious conflict. Therefore, funerals become public events where the deceased is honored, and their tangible and intangible wealth is distributed to their descendants, with the distribution determined by tradition, tribal decision-makers, and the wishes of the deceased.

As Marcel Mauss and other anthropologists have pointed out, besides inheritance, other types of free gifts are very rare in pre-modern cultures. Gifts that seem free actually imply obligations for the recipient. Before the emergence of contract law, this implicit obligation of "gifts" and the group condemnation and punishment that occur when someone refuses to comply with this implicit obligation may have been the most common motivation for delayed transactions to occur back and forth, and it remains common even today when we provide informal support to each other. In terms of our modern definition of "gifts" (i.e., gifts that do not impose obligations on the recipient), only inheritance and other forms of kin altruism have become the widely practiced forms of gifts.

Early Western merchants and missionaries often viewed indigenous people as underdeveloped races, sometimes referring to their tribute trade as "gifts" and trade as "gift exchange," believing these behaviors resembled the exchange of Christmas and birthday gifts among Western children rather than the legal and tax obligations between adults. This notion is, on one hand, a prejudice, and on the other hand, reflects a fact: at that time in the West, legal obligations were written down, while the locals had no legal documents. Therefore, Westerners often translated the terms used by indigenous people to describe trading systems, rights, and obligations as "gift." In the 17th century, French colonizers in America, scattered around more populous Indian tribes, often had to pay tribute to these tribes. Calling these tributes "gifts" was a way for them to save face among Europeans, as other Europeans did not see the necessity of tribute and viewed it as cowardice.

Unfortunately, both Mauss and modern anthropologists have retained this term. (This term implies) that these uncivilized people are still like children, and naively so, possessing a moral superiority that prevents them from succumbing to our cold-blooded economic transactions. However, in the West, especially in the formal terminology related to trading laws, "gift" refers to transactions that do not impose any obligations. When we encounter anthropological discussions about "gift exchange," these matters should be kept in mind — this term does not refer to the free or informal gifts we mean in our daily lives. They refer to the very complex systems of rights and obligations involved in wealth transfer. The only form of exchange in prehistoric cultures that resembles modern gifts is the care given by parents or matrilineal relatives to children, as well as inheritance. (The exception is that inheriting a title itself imposes the responsibilities and privileges of the position on the heir).

Some heirlooms may be interrupted over generations, but they do not form a closed loop of collectible transfer by themselves. Only when heirlooms can ultimately be used for other purposes do they hold value. They are often used in marriage exchanges between clans, thus forming a closed loop of collectibles.

Family Trade

An early important example of small closed-loop trading networks of collectibles involves the higher investment humans make in raising offspring (compared to our primate relatives) and the related human marriage systems.

Marriage, which combines long-term matching of mating and nurturing, inter-tribal negotiations, and wealth transfers, is a universal phenomenon among humans, with a history that may be as long as that of Homo sapiens.

The investment of parenthood is long-term but almost a one-time deal — there is no time for repeated selection. From the perspective of genetic fitness, divorcing a philandering husband or an unfaithful wife usually means wasting several years with the unfaithful partner. Loyalty and commitment to children are primarily guaranteed by in-laws (i.e., clans). Marriage is essentially a contract between clans, usually involving such loyalty and commitment, as well as wealth transfer.

The contributions of men and women to marriage are rarely equal; this is especially true in an era where marriage matters are decided by clans, and there are not many suitable candidates for leaders. Most commonly, women are considered more valuable, so the groom's clan must pay a fee to the bride's clan. In contrast, it is quite rare for the bride's family to give money to the groom's clan. Essentially, this only occurs in highly unequal societies with monogamy (such as medieval Europe and India) among the upper class, and ultimately, this situation is exacerbated by the significant potential advantages of upper-class men over women. Since most literature is written by the upper class, dowries often have a place in traditional European stories. This does not reflect its universality in human culture — in fact, dowries are quite rare.

Marriages between families can form a closed loop of collectibles. In fact, as long as brides wish to exchange collectibles, the two clans that exchanged members can form a closed loop. If one family is wealthier in collectibles, they can obtain better brides for their sons (in monogamous societies) or more brides (in polygamous societies). In a cycle that only involves marriage, primitive currency can replace the need for clans to rely on memory and trust, allowing renewable resources to be purchased on credit and repaid long after.

Like inheritance, litigation, and tribute, marriage requires a triple coincidence of events. Without transferable and durable value storage items, the groom's family's ability to satisfy the bride's wishes is unlikely to be satisfactory (this ability also largely determines the value misalignment between the groom and bride, of course, marriage must also meet matching political and romantic needs). One solution is to impose a long-term service obligation on the groom and his family to the bride's family. This solution has appeared in 15% of known cultures. In 67% of cases, the groom or the groom's family pays a large sum of wealth to the bride's family. Sometimes, the bride price is paid with ready consumer goods, such as plants collected or harvested for the wedding and animals slaughtered for the wedding. In pastoral or agricultural societies, most bride prices are paid in livestock (which is also a form of wealth that can last long). The remaining part — usually the most valuable part of bride prices in cultures without livestock — is often paid with the most valuable heirlooms: the rarest, most luxurious, and most durable necklaces, rings, etc. In the West, the groom gives the bride a ring (the suitor gives women other forms of jewelry), which used to represent a significant transfer of wealth and is also common in many other cultures. In about 23% of cultures (most of which are modern), there is no significant transfer of wealth. In 6% of cultures, there is mutual transfer of wealth between both genders. Only in 2% of cultures does the bride's family provide a dowry for the newlyweds.

Unfortunately, some wealth transfers are far from the altruism of inheritance and the beauty of marriage, such as tribute.

Spoils of War

In orangutan populations and even in hunter-gatherer cultures (and similar cultures), the mortality rate due to violence is much higher than the corresponding figures in modern civilization. This situation can be traced back at least to our common ancestors with chimpanzees — orangutan populations are always in conflict.

War includes killing, maiming, torture, kidnapping, rape, and extortion of tribute under the threat of such fates. When two neighboring tribes are at peace, one party usually contributes tribute to the other. Tribute can also be used to forge alliances and achieve economies of scale in war. Most of the time, this is a form of exploitation, providing greater benefits to the victors than inflicting further violence.

Generally speaking, after a victory in war, the immediate value transfer from the defeated to the victors follows. Formally, this transfer often manifests as the victors' rampant plunder and the defeated's desperate concealment. More commonly, the defeated must periodically pay tribute to the victors. At this point, the triple coincidence problem arises again. Sometimes, this problem can be avoided by complex means that reconcile the defeated's supply capacity with the victors' needs. However, even so, primitive currency provides a better method — a recognized medium of value can significantly simplify payment terms — which is crucial in an era when terms cannot be recorded or remembered. In certain cases, such as the shells of the Iroquois Confederacy, collectibles can also serve as primitive mementos, which, while not as precise as writing, can help recall the terms. For the victors, collectibles provide a way to collect tribute as close as possible to the optimal tax rate (Note: Laffer is an economist known for proposing tax cuts; his theory is that within a certain range, as tax rates increase, government tax revenue will rise; but beyond a certain point, tax revenue will actually decrease due to people’s reluctance to work). For the losers, because collectibles can be hidden, they can "underreport their wealth," leading the victors to impose less tribute on them due to the perception that they have less wealth. Hidden collectibles also provide a form of insurance against greedy plunderers. It is precisely because of this concealable nature that a significant amount of wealth in primitive societies has escaped the notice of missionaries and anthropologists. Only archaeologists can uncover these hidden treasures.

The concealment of collectibles and other strategies presents a dilemma for plunderers of collectibles that modern tax collectors also face — how to estimate the wealth they can extract. While measuring value is a challenge in many types of transactions, the difficulty is particularly acute in hostile taxation and tribute situations. After making very difficult and non-intuitive trade-offs, along with a series of visits, audits, and collection efforts, the tribute payers ultimately maximize their returns, even if this outcome is very costly for the contributors.

Suppose a tribe is to collect tribute from several neighboring defeated tribes; they must estimate how much value they can extract from each tribe. An incorrect estimation could allow some tribes to hide wealth while excessively squeezing others, leading to the gradual decline of the harmed tribes, while the benefiting tribes can pay relatively less tribute. In all these scenarios, the victors have the potential to gain more by using better rules. This is the guiding role of the Laffer curve in tribal wealth.

The Laffer curve, proposed by the distinguished economist Arthur Laffer, is used to analyze tax revenue issues: as tax rates increase, tax revenue will rise, but the increase will slow down because there will be more tax evasion, and most importantly, it dampens people's motivation to engage in taxable activities. For these reasons, there exists a tax rate that maximizes tax revenue. Raising the tax rate above the optimal Laffer rate will actually decrease government revenue. Ironically, the Laffer curve is often used to advocate for lower tax rates, even though it is fundamentally a theory about maximizing government tax revenue, rather than maximizing social welfare or individual satisfaction.

In a broader context, the Laffer curve may be the most important economic principle in political history. Charles Adams used it to explain the prosperity and decline of dynasties. The most successful governments are always guided by their own interests, maximizing their revenue according to the Laffer curve — their interests include both short-term revenue and long-term success against other governments. Governments that engage in heavy-handed taxation, such as the Soviet Union and the later Roman Empire, ultimately faded into history; governments with excessively low tax rates are often conquered by neighboring states that are better at financing. Historically, democratic governments often maintained high tax revenues through peaceful means, without waging external wars; they were among the first nations in history to have such high tax revenues relative to external enemies that they could spend a lot of money on non-military areas; their tax systems were closer to the optimal Laffer rate than most previous types of government. (There is another view that this spending spree is due to the deterrent power of nuclear weapons rather than the increasing tax revenue maximization demands of democratic governments.)

When we apply the Laffer curve to examine the relative impact of tribute contracts on different tribes, we can conclude that the desire to maximize revenue leads victors to want to accurately calculate the income and wealth of the conquered tribes. The method of measuring value critically determines how tribute payers can evade the burden of tribute through hiding wealth, fighting, or fleeing; tribute payers have many ways to deceive these estimation measures, such as hiding collectibles in cellars. Collecting tribute is a game centered around value estimation, characterized by inconsistent incentives for both parties.

With collectibles, victors can require tribute payers to pay tribute at (strategically) the most appropriate time, without accommodating the tribute payers' available time or the victors' needs. With collectibles, victors can also freely choose a time to consume this wealth without having to consume it immediately upon receiving tribute.

By 700 BC, trade had become quite common, and the form of currency was still collectibles — although currency was made of precious metals, its fundamental characteristic (the lack of a unified measure of value) was still very similar to most primitive currencies since the dawn of Homo sapiens. This situation was changed by the Lydians, who lived in Anatolia (now Turkey) and spoke Greek. In archaeological and historical records, the Lydian kings were the first issuers of metal coins.

From that time to the present, the government itself monopolizing the right to mint currency, rather than private mints, has become the primary method of issuing metal currency. Why is it not private enterprises (such as private banks, which have never been absent from these quasi-market economies) that control currency minting? The main reason people propose is that only the government can enforce anti-counterfeiting measures. However, they can enforce such measures to protect competitive private mints, just as you can prohibit counterfeit trademarks while using a trademark system.

Estimating the value of metal currency is much easier than estimating the value of collectibles — the transaction costs are much lower. With currency, trade can occur much more than just barter; in fact, many types of low-value transactions have become possible because, for the first time, the small gains from these transactions exceed the associated transaction costs. Collectibles are low-velocity currency, participating only in a few high-value transactions; metal currency has a higher velocity, facilitating a large number of low-value transactions.

Considering the benefits that primitive currency brings to tribute systems and tax collectors, as well as the inevitable value estimation problems in optimizing enforced payments, it is not surprising that tax collectors (especially the Lydian kings) became the first issuers of metal currency. The king's income comes from taxes, and he has a strong incentive to estimate the wealth held and exchanged by his subjects more accurately. On the other hand, market transactions also benefit from cheaper means of value measurement, creating a system close to an efficient market, allowing individuals for the first time to participate in large-scale markets; these are all side effects of the king's plans. The greater wealth that comes with the market also becomes taxable items, and the income the king derives from this even exceeds the Laffer curve effect brought about by reducing measurement errors under given tax resource conditions. In other words, more efficient tax collection methods, coupled with more efficient markets, result in a significant increase in overall tax revenue. These tax collectors are like those who open gold mines; the wealth of Lydian kings Midas, Croesus, and Giges has been passed down to this day.

Centuries later, Alexander the Great of Greece conquered Egypt, Persia, and most of India by plundering the temples of the Egyptians and Persians to fund his expeditions, specifically by extracting the low-velocity collectibles hidden in the temples and minting them into high-velocity coins. With this, he summoned an efficient economy and a more effective tax system.

Tribute itself cannot form a closed loop of collectibles. These tributes only have value when the victors can exchange collectibles for other things (such as marriage ties, trade, or collateral). However, victors can force the defeated into manufacturing to obtain collectibles, even if this does not align with the defeated's voluntary intentions.

Disputes and Compensation

Ancient hunter-gatherer tribes did not have our modern tort or criminal laws, but they had a similar way of mediating disputes, involving clan or tribal leaders, or voting to act as judges, covering what modern law refers to as crimes and torts. Resolving disputes through punishment or fines can prevent the clans of the disputing parties from falling into cycles of vendetta. Many pre-modern cultures, from the Iroquois in America to the pre-Christian Germans, believed that compensation measures were superior to punishment. From petty theft to rape to murder, all actionable torts had a price (such as the "weregeld" of the Germans and the blood money of the Iroquois). Where currency could be used, compensation would be paid in currency. In pastoral cultures, livestock would also be used. Besides that, collectibles are the most universal.

Compensating for damages in lawsuits or similar complaints once again leads us to the triple coincidence of events, supply, and needs, just like the issues in inheritance, marriage, and tribute. Without a solution, the judgment must compromise between the defendant's ability to pay compensation and the plaintiff's opportunity and desire to benefit from it. If the compensation is in consumer goods that the plaintiff already possesses in abundance, although this compensation constitutes a form of punishment, it may not satisfy the plaintiff — thus failing to prevent the cycle of violence. Here, we can again use collectibles to solve the problem — ensuring that compensation can always resolve disputes and end the cycle of revenge.

If compensation payments can completely eliminate grievances, then they cannot form a closed loop. However, if compensation payments cannot fully quell hatred, then the cycle following the collectibles will be one of vendetta. Because of this, such a system may reach a state of equilibrium — reducing but not eliminating the cycle of vendetta until tighter trading networks emerge.

Properties of Collectibles

Since humans evolved into small, largely self-sufficient yet mutually hostile tribes, the use of collectibles has reduced the need to record favors and made the wealth transfer systems discussed above possible; for most of our species' history, the problems these systems solve have been far more important than the throughput issues of barter. In fact, collectibles provide a foundational enhancement for the operation of reciprocal altruism, thereby extending human cooperation to realms beyond the capabilities of other species. For them, reciprocal altruistic behavior is strictly constrained by their unreliable memories. Some other species also have large brains, build their own nests, and manufacture and use tools. But no other species has created a tool that provides such significant support for reciprocal altruism. Archaeological evidence suggests that this new historical process matured around 40,000 years ago.

Menger referred to this first type of currency as "mediating goods" — which is what we refer to as "collectibles" in this text. Some handicrafts useful in other contexts (such as cutting) may also be used as collectibles. However, once tools related to wealth transfer become valuable, they will only be produced due to their collectible properties. So what are these properties?

For a specific item to be selected as a valuable collectible, it must possess the following attributes (at least relative to those less valuable products):

Safer, less prone to accidental loss and theft. For most of history, this attribute meant that items could be carried and easily hidden;

Its value attributes are harder to counterfeit. This attribute has an important subset, which includes those extremely luxurious and nearly impossible to counterfeit products, which are considered highly valuable for the reasons explained above;

Easier to estimate its actual value through simple observation or measurement. That is, reliable conclusions can be drawn from simple observation, requiring less effort.

Humans everywhere have a strong motivation to collect items that better satisfy these attributes. Some of these motivations may stem from instincts evolved with our genes. These items are collected purely for the pleasure derived from the act of collecting (rather than for any explicit or practical reason), and such pleasure is almost universally present in human cultures. One direct motivation is decoration. According to research by Professor Mary C. Stiner from the University of Arizona, "decorative items are a universal phenomenon among all modern human ancestors." For evolutionary psychologists, this behavior, which has no practical reason beyond pleasure (such as dressing up and decorating), can be well explained from the perspective of natural selection: decorative behavior is a candidate for evolution, which has turned into a pleasure that evolves with genes, stimulating collecting behavior. If the reasoning in this article is correct, this is why humans have an instinct to collect rare items, especially art and jewelry.

Point 2 needs further explanation. First, it seems very wasteful to manufacture an item simply because it is luxurious. However, these uncounterfeitable luxury items can continuously increase in value through the transfer of valuable wealth via a medium. Whenever it makes a transaction possible that was previously impossible, or makes an extremely expensive transaction affordable, a portion of the cost is recouped. The initial manufacturing cost is a complete waste, but it is amortized over time with transactions. The monetary value of precious metals is based on this principle. The same applies to collectibles; the rarer and harder to produce, the more valuable it becomes. The principle is the same for those products that can prove they contain skilled and unique human labor (such as artworks).

We have never discovered or manufactured a product that performs perfectly in all three aspects. Artworks and (modern cultural) collectibles can only satisfy (2), but not (1) and (3). Common beads can only satisfy (1), but not (2) and (3). Jewelry was initially made from the most beautiful and rare shells, but in most cultures, it eventually shifted to being made from precious metals, which provide a more balanced satisfaction of the three attributes. Precious metal jewelry is often quite thin (such as necklaces and rings), which is not a coincidence, as such products can be easily tested for quality at any location. Metal currency takes this a step further — small and standardized weights and marks used for testing significantly reduce the costs of small transactions involving precious metals. Currency itself is just another step in the evolution of collectibles.

Portable artworks created by Paleolithic humans (such as small sculptures) also meet these attributes. In fact, the items made by Paleolithic humans were either very practical or aligned with the three attributes mentioned above.

Among the artifacts related to Homo sapiens, there are some puzzling items: useless or unused flint (such as the unusable flint of the Clovis people mentioned above). Culiffe discussed hundreds of flint blades from the Mesolithic period in Europe, which were well-made but, upon closer analysis, were found to have never cut anything.

Flint is also very similar to the first type of collectibles, namely the aforementioned specialized collectibles, just like jewelry. In fact, the earliest flint may have been manufactured for its cutting purposes; used as a medium for wealth transfer, facilitating the systems mentioned above, these additional values were unexpected consequences. These systems, in turn, promoted the manufacture of specialized collectibles, first useless flint, and then the various types of jewelry developed by Homo sapiens.

Shell currency from the Sumer region, 3000 BC

In the Neolithic era, in many regions of the Middle East and Europe, some types of jewelry became more standardized — to the extent that standard size and assayability became more important than aesthetics. The quantity of jewelry used in commerce sometimes greatly exceeded that of traditionally stored jewelry. This represents an intermediate stage from jewelry to metal currency, where some collectibles increasingly adopted interchangeable forms. By 7000 BC, the Lydian kings began issuing metal coins. With standardized weights of precious metals, market participants such as workers and tax collectors could "test" their uncounterfeitable expensive attributes (through the marks on silver coins), solving the problem by trusting the reputation of the mint, rather than randomly cutting a spot on a metal coil to check its quality.

Collectibles share the same attributes as precious metal currency and most commodity-backed currencies, which is no coincidence. However, compared to the collectibles used for most of prehistory, currency achieves these attributes in a purer form.

Silver rings and coil currency used by the Sumerians in 2500 BC. Note that their cross-sectional size is also standardized. Moreover, most of these items have standard weights, ranging from 1/12 shekel to 60 shekel. To test the value of a silver ring or coil, one could use weighing and randomly selected cutting methods. (University of Chicago, Courtesy Oriental Institute)

A novelty of the 20th century is fiat currencies issued by governments ("fiat" means that the currency has no physical reserves backing it, in contrast to currencies based on gold and silver in previous eras). While fiat currency performs very well as a medium of exchange, its value storage function has proven to be very poor. Inflation has destroyed many people's "piggy banks." This explains why the market for rare items and unique artworks has thrived over the past century (because they possess the collectible attributes described above). One of the most technologically advanced markets of our time, eBay, is also filled with such items that have primitive economic attributes. The collectibles market has also grown larger than ever, although the proportion of our investments in collectibles has become smaller than when they served significant evolutionary functions.

Collectibles satisfy our primal impulses while maintaining their ancient role as a safe store of value.

Conclusion

Many types of wealth transfer, whether one-way or two-way, voluntary or forced, face transaction cost issues. In voluntary transactions, both parties benefit; gifts with no obligations are often products of kin altruism. These transactions bring value to one or both parties and are no less significant than production activities. Tribute benefits the victors; adjudication of damages prevents further violence and benefits the victims. Inheritance has made humans the first species capable of passing wealth to the next generation of relatives. These heirlooms can, in turn, be used as collateral or payment means for goods, food to fend off famine, or marriage ties. The costs of achieving these wealth transfer actions — that is, transaction costs — whether they are truly low enough for people to successfully transfer value is another question. Collectibles play a crucial role in the birth of these transactions.

Collectibles amplify our minds and language as solutions to the prisoner's dilemma, preventing us from being unable to cooperate with non-relatives through post-facto reciprocity like all other animals. Reputation mechanisms may encounter two main problems — possibly misremembering who did what and possibly misestimating the magnitude of value created by actions or the extent of harm caused. Within clans (i.e., small, neighboring kin groups, or expanded families, which are subsets of tribes), our brains can minimize these errors, so public reputation and mandatory sanctions can provide strong incentives, becoming the main driving force behind post-facto reciprocity, allowing people to avoid being suspicious and hesitant due to the cooperation and betrayal capabilities of trading partners. Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had comparable brain sizes (in this respect, they may have been similar), and it is likely that each local clan member was aware of the social networks of all others. In small kin groups, the use of collectibles for trade may be rare. However, between different clans within a tribe, the trading of collectibles and social exchanges are possible. But between tribes, collectibles completely replace reputation, becoming the driving force of reciprocity, although violence still plays an important role in enforcing rights and becomes the main obstacle to most transactions.

When items embody uncounterfeitable expensive consumption — trade glass beads, manufactured in Venice in the 16th or 17th century, unearthed in Mali, Africa. Such beads were very popular wherever European colonizers encountered Neolithic or hunter-gatherer cultures.