Original author: PATRICK MCCORRY

Original translation: Luffy, Foresight News

Any database that interacts with cryptographic assets will eventually choose Rollup as its technical stack. There are many good reasons why developers make this decision:

Real-time auditing

Default solvency proof

Optional custody of user funds

Honest participants can protect the entire system

Most importantly, all the design and implementation work of Rollup is focused on protecting users, their funds, and all their interactions from potential unknown and powerful system operators.

Even if the entire system is offline, users can still reclaim their funds on their own.

If Rollup can be widely deployed as a technical stack, then we may have the ability to break down trust barriers, allowing anyone in the global community to engage in financial interactions, ushering in a new era of global e-commerce, remote recruitment, and frictionless service provision.

To make Rollup work properly, a lot of effort is indeed required.

What about multi-signature?

This sounds good, but the entire system is ultimately controlled by multi-signature. If the signers are compromised or act maliciously, they can easily steal all the funds.

So, who cares about Rollup? Somewhere on CT.

Indeed, all current Rollups have multi-signature, with the authority to upgrade the underlying smart contracts, but as we will see, it is a conservative mechanism to protect user funds and is part of a broader system architecture.

Responsibilities of the Security Council

Multi-signature is a technical term that refers to a system that requires multiple signers to authorize an operation. For example, N out of K signers must complete digital signatures for a transaction to be allowed.

In the context of Rollup, multi-signature is often referred to as a Security Council, with signers empowered to upgrade all relevant smart contracts.

Let's take a look at the types of responsibilities that the Security Council in Arbitrum may assume (because I am very familiar with it):

Veto power. If the Security Council believes that a proposal passed by the Arbitrum DAO violates the Arbitrum constitution and may harm the Arbitrum ecosystem, it can cancel the proposal. For example, canceling a proposal passed due to governance attacks.

Maintenance. Upgrade the Arbitrum smart contract suite for minor changes that do not require involvement of the Arbitrum DAO.

Emergency events. Respond quickly in emergency situations, and if they believe that user funds are at imminent risk, they can urgently upgrade smart contracts.

Of course, the most important responsibility of the Security Council is to respond to emergency events and take action promptly to protect user funds.

Members of the Security Council need to be very trustworthy individuals.

People trust that the signers can respond quickly, upgrade smart contracts in emergency situations, and believe that they will do their utmost to protect the funds in the smart contracts.

Choosing the right multi-signature threshold

When deciding to establish a Security Council, two important factors need to be considered:

How many signers in total?

How many signers at least are needed to approve an action?

This may seem like a trivial issue, after all, it's just two numbers, but a balance must be considered:

Security breach: K members may collude to change smart contracts and steal user funds.

Liveness breach: N-K+1 members may collude to prevent any changes to smart contracts, which is particularly serious if serious vulnerabilities are discovered.

The difficulty lies in determining a threshold that can maintain fund security in peacetime and take prompt action when user funds are threatened in emergency situations.

Let's consider a specific example. Suppose the threshold is set to 9/10, where 9 signers must jointly sign a message. This is a stringent security threshold, as it requires collusion of 9 signers to steal funds. However, the downside is that any two signers can prevent any action in emergency situations. For example, if two signers are on a transatlantic flight, the Security Council will be unable to fulfill its duties.

Of course, if the security threshold is lower, say 2/10, then user funds can be stolen with collusion of any two signers (or if a private key is leaked).

The view of a person's integrity is likely to change over time

Choosing the appropriate threshold is more of a social issue than a technical issue, and I believe it is more of an art than a science. Security largely depends on the integrity of individual signers. As we will soon see, there are some methods to reduce trust in multi-signature, but this brings a series of trade-offs.

Security Council Members

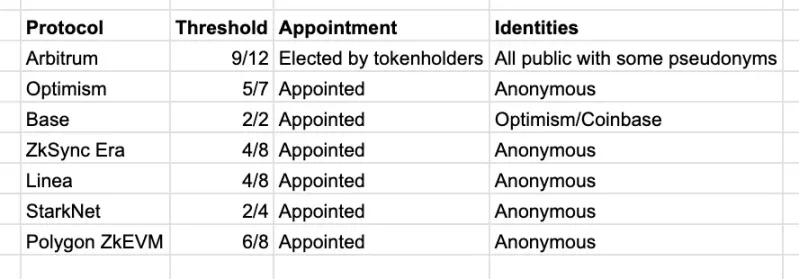

The main Rollup instant upgrade multi-signature threshold for all smart contracts

Most Rollups have a group of anonymous signers in their Security Council. We suspect this may be due to:

The development stage of Rollup,

Protecting the personal safety of members,

Believing that anonymity is the best choice to protect user funds.

On the other hand, three Rollup projects have publicly announced the identities of their Security Council members:

Arbitrum: Signers are elected publicly, and the current list can be viewed on Tally. Only three signers are relevant to the Arbitrum project (two from Offchain Labs and one from the Arbitrum Foundation).

Base: 2/2 multi-signature, one controlled by Base and the other by Optimism.

PolygonzkEVM: Not yet implemented, but they have announced that they will upgrade their multi-signature to 10/13, including two members from Polygon Labs and one advisor from Polygon Labs.

zkSync Lite: zkSync Lite should be distinguished from ZkSync Era, and its Security Council is publicly announced and does not include direct affiliates of the Rollup project (excluding zkSync's investors).

In Arbitrum and in the upcoming Polygon, only a small number of signers are directly relevant to the Rollup project, and the number is small enough to ensure that affiliates cannot collude to prevent action by the Security Council. In zkSync Lite, they have appointed signers independent of the project, in addition to zkSync's investors.

In all cases, Rollups place great importance on signers who are not directly related to the project.

However, there seems to be a lack of consensus on how to form a good multi-signature, which presents us with several design issues:

Should anonymous members be allowed?

Should members come from different regions?

Should members be individuals or companies?

Should members be appointed or elected?

How many members from the same company (or country) should be allowed?

Is there a minimum scale and threshold considered appropriate?

The general rule of thumb should be to select highly trustworthy members so that the public can have confidence in the security of the system. At least, I believe most projects would likely do so, even if it's not always verifiable.

Note that the six members of the Arbitrum Security Council have been pre-appointed, but they will be replaced in the March election.

Weakening the Council's Power

So far, we have only considered a council with the authority to immediately upgrade smart contracts, but there are some methods to limit the council's power:

Time delay. All operations authorized by the council will only be executed and take effect after time T has passed.

Pause-only. All assets held by the native cross-chain bridge can be frozen by the council. This may pause the following functions:

Passing messages from L2 to L1 (i.e., withdrawals),

Completing the sorting of pending transactions,

Completing new checkpoints/certificates,

Accepting new Rollup data (i.e., pending transactions).

Bypassing the council. Abandoning the council and relying on another governance mechanism (such as a DAO) to approve upgrades.

Of course, this would limit the council's ability to take prompt action and effectively respond to emergency events threatening user funds.

If a vulnerability has been privately disclosed to the council but has not been exploited by hackers, the council can choose to upgrade smart contracts and fix the error. Adding a time delay to the upgrade would increase the risk of attackers researching publicly disclosed upgrades, finding vulnerabilities, and exploiting them.

For example, the CVE-2018-17144 in Bitcoin was initially publicized as a DDoS vulnerability, while attempting to conceal a more serious token inflation vulnerability. The speed of the upgrade is crucial to prevent it from being exploited.

Evaluating the Defense Capability of the Pause-only Mechanism

Let's consider potential scenarios where attackers actively exploit vulnerabilities:

Malicious L2 → L1 messages. Attackers can craft arbitrary messages originating from smart contracts on the Rollup and forward the messages through the native cross-chain bridge to smart contracts on Ethereum.

Invalid state transitions. Attackers can execute transactions on the Rollup that violate state transition function rules, which should typically be considered invalid.

Withdrawal vulnerabilities. Attackers can extract funds from the native cross-chain bridge by simply issuing a transaction on Ethereum (Layer 1).

In all three cases, a time delay would only give attackers more time to continue stealing funds and reduce the council's window of opportunity to defend the system. The delay function cannot defend against active attacks and can only be used for routine maintenance and non-urgent tasks.

We will only evaluate the capability of the pause system and the extent to which the system can be paused.

In the case of malicious L2 → L1 messages, the pause function can mitigate the attack without disrupting transaction activity. The council should pause message passing and/or the finalization of new checkpoints. There is a viewpoint that L2 → L1 messages should have a time delay before execution, allowing the council time to detect errors and respond to emergency events.

Defending against invalid state transitions is more challenging because transaction finality on the Rollup has different layers. If we only consider Rollup transactions without any side effects, the best defense of the Security Council is to stop the finalization of checkpoints but continue to allow transaction sorting. This can allow time to fix errors, reactivate checkpoint finalization, and simply ignore invalid transactions.

However, if transaction activity on the Rollup is not halted, the user experience will be chaotic, and the Rollup may be in a severely compromised state until client software upgrades.

This leads us to the next scenario. If we consider how invalid transactions on the Rollup may affect other systems, how should the council respond? The best defense is to freeze the ability of the native cross-chain bridge to finalize transaction sorting or to completely shut down the sorter.

This is because some systems, such as fast cross-chain bridges for transferring funds from one Rollup to another, may authorize fund transfers once they believe Rollup transactions (including invalid transactions) have been sorted. In this example, it could allow attackers to exploit DeFi protocols on the Rollup and then quickly transfer the funds to another Rollup via a fast cross-chain bridge.

By the time the council fixes the vulnerability and restores invalid transactions, the damage may already be done. Both the DeFi protocols and LP in the cross-chain bridge may suffer losses from the attack.

Finally, if the vulnerability allows attackers to directly extract funds from the native cross-chain bridge, similar to NomadHack, the Security Council may be powerless to prevent it.

The pause mechanism presents a final overarching issue. We must assume that there is a broader governance system that can approve upgrades and reactivate the Rollup. If we assume that the governance system is a DAO with an on-chain voting system running on the Rollup, there are tricky implementation issues.

For example, if the L2 → L1 message cross-chain bridge is paused, the results of the DAO's vote cannot be passed from the Rollup to the native cross-chain bridge on Ethereum, and an alternative method must exist for the DAO to send approval messages and execute upgrades.

Gradually Phasing Out the Security Council

Some in the community believe that the Security Council should be gradually phased out, but in my view, this would bring two problems:

False sense of security. Attackers who understand the exploitation of vulnerabilities will wait until the Security Council is gradually phased out before executing attacks. Over time, this would weaken our confidence in the security of the system.

Limited recovery options. Without the Security Council, the community would be unable to counter attackers. The only available option would be parallel white-hat hacker attacks, hoping to reclaim some funds.

I believe that the Security Council is always necessary, but the power granted to them should be gradually reduced.

With this in mind, the design issues should be:

How can we allow the Security Council to pause the system with minimal impact on users, while also allowing broader community involvement in deciding how to fix errors and reactivate the system?

In other words, we need a solution that truly allows community intervention and system recovery, and then limits the pause power of the Security Council.

In the field of Layer 1 blockchains, the community can indeed directly achieve this through user-activated forks, but this method is not applicable to smart contracts on Ethereum (such as Rollups) as there is no need to fork the entire Ethereum. In some cases, the Ethereum community may collectively decide to save the Rollup, as in the case of TheDAO in 2016, but Rollups should never rely on or expect such an outcome.

Another interesting idea along these lines is to implement an Ethereum Supreme Court to decide on smart contract upgrades and enable a user-activated fork similar to the DAO.

As mentioned earlier, if a Rollup delegates its security to a DAO, there should be an implementation that allows the DAO to vote directly on Ethereum. This is very tricky, especially if the voting protocol exists on the Rollup.

Finally, I believe there should be a comprehensive review of the types of scenarios that may require a response from the Security Council to help inform discussions around its necessity.

If there is multi-signature, why worry about Rollup?

We have spent quite a bit of time understanding the responsibilities, design, and requirements of the Security Council, but it's important to return to the initial question of this article:

Is Rollup just multi-signature?

The answer is no.

To help understand why, it's best to take a step back and understand what blockchain systems really aim to achieve.

Blockchain protocols are a tool that allows users to compute replicas of a database and be confident that they have the same database as others.

With this in mind, any blockchain system has two components:

Blockchain protocol. A combination of software, cryptography, and distributed systems that instills confidence in anyone about the integrity of the database.

Governance system. A coordination mechanism that allows all stakeholders to work together and agree on changes to the blockchain protocol.

The goal of any blockchain system, including Rollup, is to ensure that the blockchain protocol runs with an extremely reliable uptime of 99.9999%. Trusted system operators should have minimal interference with the day-to-day operation of the system. Ultimately, the responsibility for protecting user balances, smart contract code, and state lies with software, cryptography, and distributed systems.

At times, it is necessary to change the blockchain protocol to improve user interests. The community may want to address configuration issues, add new features, or respond to critical vulnerabilities threatening system integrity. This requires manual intervention and can only be invoked 0.0001% of the time.

The governance system is responsible for implementing manual interventions, and over the years, several methods have emerged:

Centralized party: One party can unilaterally decide how to upgrade the system (many projects, including Bitcoin, started this way).

Rough consensus: The majority of participants indicate their readiness to deploy an upgrade, determine a flag day, and then execute the upgrade (Bitcoin/Ethereum).

Voting protocol: Parties participate in elections and explicitly vote to approve upgrades.

Immutable: Smart contracts can be immutable, and the system can never be changed.

In addition to the above, the community can also decide to appoint a Security Council as a supplementary option for governance to take swift action in emergency situations.

The Security Council does not prevent attacks. It is a passive mechanism that works in conjunction with governance when user funds or the reliability/performance of the blockchain protocol are under attack.

Conclusion

All discussions surrounding blockchain protocols, governance, and Security Councils are crucial. The existence of these discussions makes cryptocurrencies so special.

This is a great example of trust engineering: focusing on the engineering discipline of identifying, measuring, and reducing/eliminating elements of trust in a system.

In cryptocurrencies, we focus on building systems that not only protect users from powerful system operators but also enable the system to operate reliably (safely) under the most adverse conditions.

This is why it is healthy for community members to maintain skepticism about the role of the Security Council, but they also have a responsibility to propose better solutions in a passive manner to protect user funds during emergency events.

I hope this article clearly explains why Security Councils are useful, why they are necessary today, but also that they are only a small part of the broader architecture of smart contract systems.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。