原文标题:《The Fall and Rise of American Finance》

原文作者:Scott M. Aquanno、Stephen Maher

原文编译:MicroMirror

4:新自由主义与金融霸权

从沃尔克冲击中出现的新自由主义资本主义首先以一种新的金融霸权形式为特征。金融的兴起不仅体现在金融部门的力量不断增强,也体现在工业企业自身金融逻辑和运作的重要性日益增加。后者越来越像一家金融机构,因为顶级企业高管不仅在内部企业运营中分配投资池,而且在提供更便宜劳动力的外部分包商中分配投资,尤其是在全球外围地区。通过这种方式,非金融企业的持续金融化促进了生产的全球化。

然而,随着布雷顿森林新政秩序的资本管制和障碍被重组和抛弃,资本积累无缝世界的出现也依赖于全球金融的一体化。这些金融化和全球化进程恢复了工业盈利能力,最终结束了20世纪70年代的长期危机。这种融资为随后几十年深化全球化提供了必要的基础设施,使金融和工业资本的利益更加紧密地交织在一起。无论是在工业企业内部还是外部,金融的兴起都增强了资本的流动性和竞争力,并使精简资本积累的新世界成为可能。

一个更加专制的国家的出现,特别是以权力集中在美联储为特征,是全球化和金融化不可或缺的一部分。美联储与民主机构的隔离(或“独立性”)是必要的,以确保其有能力进行快速、灵活和国际协调的干预,以满足僵化的全球贸易和货币秩序的要求。与此同时,该州越来越依赖债务而不是税收来为其支出提供资金,这限制了财政政策,并进一步加强了美联储的权力。与合法化相关的国家机构,包括代议制民主结构、政党、福利国家计划和工会权利,被撤销或掏空。一个围绕其积累功能紧密组织的威权新自由主义国家的出现意味着一种更赤裸裸的强制性国家权力形式。

在新自由主义时期,成为霸权的金融资本不仅包括银行,还包括不同机构的相对分散的融合。与定义金融资本的银行对公司的直接控制不同,现在形成的是一种多集权的金融霸权形式,在这种形式中,相互竞争的金融机构在公司董事会上建立了短暂的联盟,以施加广泛的影响和纪律。最重要的是商业银行和投资银行,但这一部分也包括共同基金公司、养老基金、保险公司、对冲基金和经纪交易商。正如我们将看到的,这些公司相互联系,形成了新自由主义时期发展起来的独特的市场金融体系,非银行金融机构在信贷和货币创造方面变得更加重要。正是这个体系成为了2008年危机的中心。

非金融公司的金融化

金融霸权的出现反映在金融和工业之间剩余价值分配的转移上。正如我们所看到的,在管理时代,金融相对于工业的弱点表现在其通过利息和股息支付从工业企业中提取盈余的能力有限。因此,工业企业能够以留存收益的形式持有生产中产生的更大一部分剩余价值。随后,金融力量的不断增强反映在其获得越来越多的盈余份额的能力上。如图3.1所示,在整个管理期间,留存收益在GDP中所占的比例始终高于股息支付。引人注目的是,这种关系在1980年急剧逆转,此后股息支付在GDP中所占的比例一直高于留存收益。

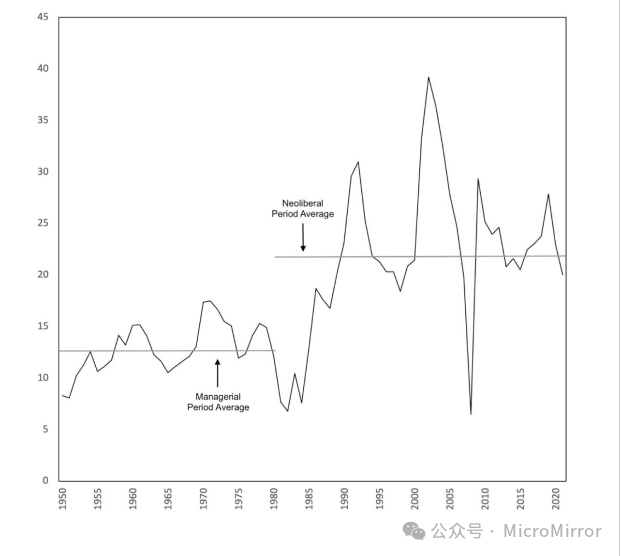

同样,在管理时代,工业企业在收入和利润方面甚至使最大的金融机构相形见绌,而在新自由主义时期,这一点也发生了逆转。1960年,只有一家银行(美国银行)被列入美国20家最赚钱的公司之列;到2000年,前五名中有两家是银行,前二十名中有五家是金融机构。然而,即使是这些数字也往往低估了金融机构的重要性。比盈利金融公司的数量更能说明问题的是这些公司在公司总利润中所占的份额。这一相对较少的金融公司在企业利润总额中所占的份额从战后初期的8%上升到2001年的40%以上(图4.1)。因此,金融在不断增长的整体中所占的比例越来越大。

图4.1:1948-2021年财务利润占总利润的比例(%)

资料来源:经济分析局,作者计算。注:“新自由主义时期平均值”涵盖1980年至2008年。其他财务利润占国内产业的份额。

20世纪80年代,T.Boone Pickens和Carl Icahn等所谓的公司掠夺者对工业公司进行了敌意收购,这是股东和管理者之间权力关系深刻转变的首批迹象之一。这种“突袭”包括用借来的钱购买一家公司的控股权,解雇首席执行官,然后卖掉公司的资产来偿还债务。突袭者通过德崇证券(Drexel Burnham Lambert)等一度声誉卓著的投资银行安排的“垃圾债券”获得融资,德崇证券是垃圾债券之王迈克尔·米尔肯(Michael Milken)的雇主,米尔肯以其年度“捕食者之球”而闻名,而这个球上挤满了这些粗鲁的新华尔街人群。这些投资银行愿意承销高风险、高收益的债券,前提是一旦目标公司被接管,他们将用目标公司的资产偿还债券。

杠杆收购对工业企业经理来说尤其令人担忧,因为它们允许缺乏信誉的掠夺者几乎完全用借来的资金购买目标公司的控股权。这实际上意味着任何人都可能成为威胁。公司经理们的回应是通过建立“毒丸”和“金降落伞”等防御措施来保护他们的公司。在前者中,现有股东可以选择在发生敌意收购企图时以折扣价购买额外的股份。这有助于阻止一位反对的激进投资者巩固足够大的股权,从而影响管理层的更迭。在后者中,高管们确保在因收购而被解雇的情况下为自己提供过高的薪酬。

保持高股价有助于防止此类收购企图。事实上,在掠夺者眼中股价被“低估”的公司是潜在收购的主要目标,因为它们可以相对便宜和容易地被收购。保持高股价会提高收购公司的成本,从而减少甚至消除从分割和转售资产中获得的利润。因此,管理者试图通过执行所谓的股票回购来防止此类威胁,即公司通过回购自己的股票来抬高股价,这是美国证券交易委员会于1982年合法化的做法。除了股息支付外,这一时期股票回购的增加还反映在留存收益占GDP的百分比下降上,这是金融获得更大份额盈余的重要机制(图4.1)。

因此,回购以及增加股息支付是工业企业对新兴金融霸权的战略回应。它们构成了“股东价值”学说的核心部分,根据该学说,公司战略应更加注重提高股价。在企业掠夺者的拥抱下,这种意识形态成为了金融权力新时代的名片,因为本应自满的工业管理者面临着新的纪律。通用电气首席执行官杰克·韦尔奇成为新学说的最重要的大师。其他人的适应速度较慢。但随着越来越自信的董事会开始解雇未能改善股价的管理层,最突出的是1992年的IBM和1993年的通用汽车,很明显,即使是最大、最强大的公司,也别无选择,只能屈服于投资者的力量。

多集权金融霸权的出现是由大型金融机构手中的股权集中和集中所支撑的。这是由机构资产所有者,特别是养老基金控制的货币资本池推动的。具有讽刺意味的是,此类基金的激增反映了20世纪60年代工会在集体谈判中的实力。到20世纪70年代中期,养老基金已成为公司股票的最大单一持有者。虽然这导致一些人猜测“养老基金社会主义”的到来,但这些基金最终有助于将阶级力量的平衡转向资本,并加剧了重组非金融公司的金融压力。国家鼓励此类基金的增长,因为对公司和工人的税收激励在将养老金计划覆盖范围从1950年的五分之一扩大到1970年的近一半方面发挥了重要作用。

因此,大型金融机构直接拥有或间接管理了很大一部分可用股权。1940年,金融机构的股票持有和股票交易占美国所有股票市值的不到5%。到20世纪70年代中期,它们约占25%,到2008年跃升至70%。4然而,即使是这些数字也往往低估了这一时期正在进行的集中和集权的程度。虽然大型机构投资者对股票所有权的集中显然非常显著,但这些机构积累的大量股权随后被管理它们的其他投资公司合并,从而形成了更大的所有权。

大型机构投资者聚集的股权规模意味着,他们很难通过简单地抛售股票来约束表现不佳的公司,因为这可能会压低他们剩余持股的价值。因此,投资者寻求其他方式施加影响,包括与管理层建立更直接的联系。他们还推动建立更强大、更独立的董事会,在管理期间,董事会主要由内部人士控制。同样,股东可以行使投票权来更换管理层、提名外部董事,或通过“代理权之争”以其他方式影响公司战略。到20世纪90年代,代理权之战比敌意收购更为常见,这与20世纪80年代的模式截然相反。到21世纪初,它们几乎是施加投资者压力的唯一手段,反映了新等级制度的正规化和巩固。

那些曾经是行业统治者、处于公司权力金字塔顶端的人越来越发现自己要对投资者负责,他们和他们在商业媒体上的盟友经常被指责过于关注短期盈利能力,而缺乏对特定行业或公司的必要知识。但如果很明显,金融的崛起与资本市场在分配社会盈余方面所谓的“完美效率”关系不大,那么金融也不仅仅是一种食利者的利益。相反,它正在成为一支强大的工业生产纪律部队,无情地推动其投资实现最大利润。金融化带来的利润率提高和资本流动性增强不是“空心化”或削弱产业的问题;相反,金融加剧了企业重组运营的压力,以降低成本,最大限度地提高效率、竞争力和盈利能力。

与此同时,国家机器的战略、法规和结构的转变支持了围绕金融资本上升地位的权力集团的重组,从而形成了一个新的政治等级制度。新政监管架构的基础是美联储、货币监理署、联邦存款保险公司和美国证券交易委员会采取行动,维持银行系统的碎片化,限制其参与公司治理,即防止金融资本的重新出现。然而,强大的机构投资者现在发现这些做法“艰巨、令人困惑、昂贵且普遍令人失望”。20世纪90年代,美国证券交易委员会颁布了一系列监管改革,扩大了“股东权利”并赋予董事会权力。特别重要的是,改革使大股东更容易就他们持有股份的公司相互协调,促进了可能挑战内部人士的投资者联盟的形成。

这些监管转变大大降低了进行代理权争夺的成本,并直接导致了与敌意收购相关的代理权争夺频率越来越高。重要的是,这些变化是为了应对20世纪80年代建立的对投资者纪律公司的防御而实施的。除了采用毒丸和金降落伞外,工业管理者还试图获得联邦反收购法的保护。当一个缺乏同情心的里根政府拒绝了这些努力时,工业高管们转向了州一级,在那里他们往往是最大的雇主。不出所料,这些努力取得了更大的成功:到1990年,42个州纳入了此类保护措施。随着20世纪90年代的监管重组,美国证券交易委员会采取行动抵消这些防御措施并限制其影响,通过为投资者提供更有序的行使影响力的手段,使投资者的权力制度化。

因此,美国证券交易委员会介入了金融和工业之间的冲突,并为建立金融霸权做出了贡献。但这并不意味着它已被金融“俘获”。经济机构的重组不仅反映了特定企业对国家的影响,还反映了金融在积累结构中的重要性。稳定财政权力需要在工业公司中建立“问责制”和“善治”。这也反映在美国证券交易委员会推出的一系列其他新规定中:虽然萨班斯-奥克斯利法案增加了董事会的权力和独立性,但FD条例阻止了向大型机构投资者披露内幕信息的特权。特别是后者,似乎旨在防止内部经理和股东之间出现客户关系。

但非金融公司的金融化不仅仅是外部金融家迫使工业企业进行重组的问题。正如我们所看到的,金融化的根源可以追溯到战后黄金时代的核心,因为企业对多元化和国际化的复杂性做出了回应。因此,尽管加强了对投资的集中控制,但非金融公司已经分散了运营。这导致了公司财务部门在组织中的权力越来越大,因为它负责设计和实施定量指标,为在定性不同的生产过程之间建立等效关系奠定了基础。只要这些数量是以普遍等价物来衡量的,货币资本就会调解公司不同业务之间的关系。

这相当于金融和工业资本融合的逐步发展。19世纪,这种融合是通过投资银行和工业企业之间的互联建立的,而现在,一个世纪后,这表现为工业企业内部资本的M-C-M′和M-M′回路的融合。尽管新政的规定旨在严格区分这两种形式的资本,但这种情况还是出现了。事实上,这些规定的直接结果是工业企业将一系列金融实践内部化,而这些实践以前依赖于投资银行。这些监管障碍实际上激励了工业公司提供金融服务,因为它们能够逃避正式指定的金融机构面临的监管。公司内部金融和工业资本之间的这种新兴融合,以及作为投资体系的重组,尤其是首席财务官(CFO)的崛起。虽然1963年没有大公司有首席财务官,但从20世纪70年代开始,商业世界的公司开始设立这样的职位,到20世纪90年代,这种职位几乎无处不在。首席财务官的崛起反映了公司管理逻辑的根本性变化,现在这种逻辑更加突出了明显的“财务”考虑。公司财务主管一直是一个相对沉闷而平凡的职位,主要负责簿记、税务等工作;现在,首席财务官是二把手,是首席执行官在制定公司战略各个方面的得力助手

首席财务官的任务是评估业务部门的绩效,制定利用财务杠杆支持公司整体竞争力的战略,管理收购和资产剥离,并抵御敌意收购企图。他们也是与投资者和金融分析师的主要联系,特别是通过他们管理“投资者关系”职能。除了提供数据和做出决定“投资者预期”的预测外,首席财务官们还推动了公司实现这些预期所需的纪律。正如首席财务官的影响力反映了公司分权后财务业务的扩张一样,这种权力对于推动进一步的金融化重组以满足外部投资者的需求也是必不可少的。因此,首席财务官是股东价值的主要支柱,体现了公司内部外部投资者的新力量。

工业公司内部金融和工业的融合意味着它开发了一系列金融功能,这些功能并不严格服从于它所控制的工业资本回路。工业公司不仅越来越多地围绕公司内部有息资本的流通进行组织,而且还从公司外部的流通中获利。工业公司最初因管理期间留存收益的积累而大规模放贷,否则这些留存收益将闲置或相对无利可图地存入银行。事实上,到黄金时代结束时,工业公司已经成为商业票据市场的主要贷款人,就像他们在这些市场上从其他公司大量借款一样。

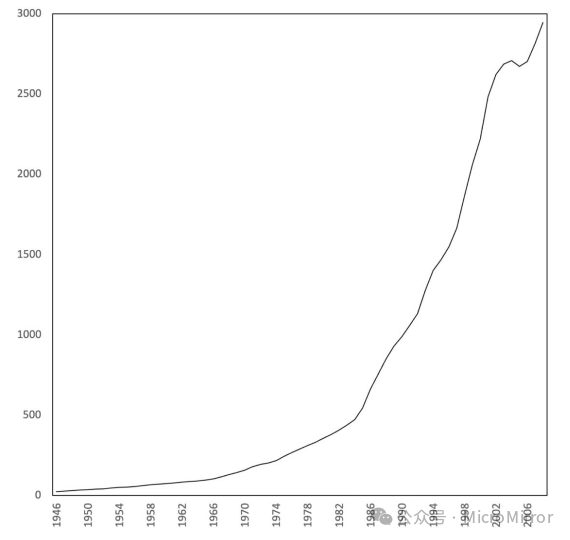

在新自由主义时期,非金融公司与金融市场的融合急剧加速。图4.2显示了在新自由主义时期,市场上流通的非金融公司发行的债券总数急剧增加。1984年取消了对此类债券对外销售的限制,有效地使美国公司债务市场全球化,并大幅扩大了非金融公司的融资范围,从而改变了这些市场。公司对债券的更大依赖也意味着他们以新的方式受到这些市场的约束:随着公司开始依赖债券作为不可或缺的融资来源,他们也越来越关注对其信誉的评估,尤其是反映在债券价格上

图4.2:1946-2008年非金融公司债券总额(十亿美元)

资料来源:FRED,作者计算。注:年均,十亿美元。

衍生品对资本全球流动的重要性是促使公司内部工业和金融资本融合的另一个因素。在布雷顿森林资本管制和固定汇率时期,公司通过“跳过”关税墙在国外投资,建立子公司,生产产品在特定经济区内销售。然而,新自由主义时期取消关税保护,使全球生产得以精简。多余的设施被拆除,生产阶段位于劳动力、监管和税收成本最低的地方。其结果是创建了无缝、全球一体化的生产网络。事实上,世界“贸易”的很大一部分是通过跨境企业生产链进行的产品和资本流动。

跨境流动资本带来的风险是,意外的汇率和利率波动可能会在成品进入市场之前就将其价值抹去。公司通过签订衍生品合约来管理这些风险:在20世纪80年代初至2007年期间,衍生品的日交易额增长了50倍,从几乎为零增长到近2万亿美元。衍生品确保了在未来以固定价格购买资产的权利,有效地“锁定”了给定的价格。因此,它们将风险转移给投机者,投机者愿意承担风险,以换取获得可观利润的可能性。通过这样做,他们建立了固定汇率的一些一致性,尽管是在一个浮动货币市场波动的世界里。因此,衍生品在剩余价值的生产和实现过程中调节了工业资本的连续性。

在衍生品合约中,一方支付一笔费用,称为溢价,以换取对不稳定事件(例如汇率突然变化)的保护。如果发生这种情况,约定的金额将转移给合同持有人,以弥补部分或全部损失。为了值得信赖,衍生品合约必须由信誉良好的第三方管理,该第三方可以监督合约双方之间的资金流动。这一角色由大型银行扮演,它们传递费用和保费,并在合同结束时结算最终付款。因此,银行通过将其在全球金融体系中的中心地位转化为在扩大衍生品市场中的独特作用,创造了新的收入。除了通过收取服务费来获利外,银行还自己签订衍生品合约来对冲自身风险

正如我们所看到的,竞争是资本流动的函数。就促进投资流入和流出部门、设施和地理区域而言,企业金融化强化了对工业资本(以最大限度地提高利润)和工人(对工资和工作条件施加下行压力)的竞争纪律。与管理时期的常态不同,从利润较低的业务中撤资成为采用新的“投资组合管理”的公司的常规做法,而不是无休止地扩大规模。金融化公司从这种从相对无利可图的部门撤资的能力中获得了竞争优势,同时快速评估和投资于利润更高的部门。

到20世纪90年代末,这些趋势最终以第二次世界大战后几十年形成的多部门企业集团形式的企业组织被新的多层子公司形式所取代。越来越多的工业公司不仅在自己的业务部门组织生产,而且还与提供更便宜劳动力的外部公司签订分包合同,这些公司通常位于全球外围。因此,跨国公司将外部分包商及其内部部门整合到全球生产和投资网络中。这些分包合同的灵活性进一步加剧了工人及其所在国家在投资和就业方面的竞争压力,压低了工资,限制了麻烦的环境和劳动法规,同时为跨国公司提供了相对容易的搬迁能力。

多层附属形式是资本主义全球化发生的组织结构。这些跨国公司之所以处于全球政治经济的顶端,是因为它们拥有两种独特的金融资产:品牌和知识产权。这两种形式都是国家授予的垄断权,因为这些资产的所有权赋予了对制造某些产品或使用特定品牌的独家控制权。然后,跨国公司通过与分包商签订许可协议来确保对生产的控制。通过这种方式,多层子公司形式对生产的权力是根据公司围绕金融资产管理的进一步重组而构建的。

因此,对于金融的崛起来说,比金融和工业资本之间盈余分配的变化更重要的是其在资本积累组织中不断变化的系统功能。20世纪80年代和90年代展开的新自由主义全球化进程导致了金融和工业之间纠缠的加深。无论是在公司内部还是外部,融资对于投资的流动性都至关重要,这使得工业企业能够创造一个全球一体化积累的新世界。金融化远非衰退的症状,而是为工业企业和金融机构带来了繁荣的新时代。金融在美国社会形态中日益增长的力量反映了其作为全球资本主义神经中枢的地位。

资产积累与市场金融

非金融公司的金融化重组和大型机构投资者的崛起,都是以金融资产所有权和控制权为基础的新型积累形式的发展为前提的。这种基于资产的积累模式是由非现金金融资产作为金融和非金融公司货币资本形式的重要性日益增加所定义的。资产积累是新自由主义时期形成的市场金融体系的重要组成部分,金融体系及其信贷生成功能围绕资产的拥有和交换进行重组。市场金融将养老基金与投资银行、商业银行和其他金融机构整合在一起。

基于资产的积累的一个基本前提是,将更广泛的有形和无形对象和过程定义、构建和监管为抽象的金融资产。例如,随着非金融公司的高层管理人员越来越多地成为货币资本家,公司本身同时也围绕着将其各种具体的业务运营(跨时间存在的工业资本积累过程)客观化为抽象的金融资产而构建。这促进了这些产业电路在货币资本逻辑中的整合,货币资本逻辑在企业中越来越占主导地位。与此同时,金融体系本身的运作越来越以分解经济过程并将其重组为不同类型的可交易金融资产为前提。

金融资产是货币资本的具体形式。它们的主要特征是能够通过销售或其他合同安排(例如,使用知识产权的许可协议)确保对未来收入的财产索赔。从棒球卡到达·芬奇的杰作,从贷款到知识产权,只要融入货币资本的M-M循环,一切都可以成为金融资产。作为资产,这些东西所具有的唯一使用价值是它们通过交换转化为大量货币的能力。事实上,正如我们在第2章中看到的,金融资产的货币性质取决于它们储存价值的能力,从而转化为普遍等价形式(即货币)。正是通过货币交换,资产价值的收益得以实现,M-M’电路得以完成。

不同类别和形式的资产在普遍等价形式中不断竞争其估值。作为资产(即股票),公司不仅与所有其他公司,而且与从艺术品到房屋的所有其他金融资产都处于竞争关系中。因此,基于资产的积累加深了货币形式在工业企业内部和整个经济中的渗透。这对企业施加了巨大的约束,对其战略甚至产业资本本身的结构都产生了深远的影响。人们不能将资产仅仅视为虚拟资本,存在于与“实体”经济分离的独立金融领域。相反,资产化使金融及其竞争压力比以往任何时候都更深入地投入生产。

资产积累通过非银行金融机构内部的股权集中,支持了金融霸权的重新出现。在马克思的金融积累模型中,银行将一笔货币资本预付给运作中的资本家,资本家控制资本,直到贷款从生产中产生的盈余中偿还利息。金融家提供给实业家的资本,然后凭借其对该资本的产权,再加上利息,流回其所有者。然而,由于在新自由主义时期支撑金融霸权的非银行金融机构不发放银行贷款,他们无法以这种方式以利息支付的形式从公司中提取剩余价值。因此,他们不得不通过其他方式从工业企业创造的价值中“分得一杯羹”。

他们这样做的一种方式是通过股息支付。事实上,正如我们所看到的,股息支付的增长反映了金融力量的增强。然而,股息是由董事会逐年决定的,而不是在收到贷款之前通过合同安排确定的。因此,股息往往以其他利息支付所没有的方式波动。因此,对机构投资者来说,更重要的是资产估值,即股票价格本身。虽然利用这些估值并不等于直接转移剩余价值,但它确实使股票持有人有权获得社会总产品的更大份额。因此,机构投资者通过分期付款和增加股票价值来积累财富。

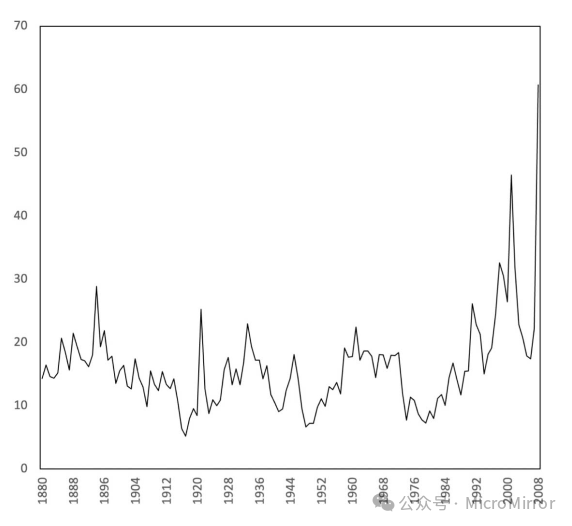

很明显,金融和工业之间的利润分配不足以理解新自由主义时期金融权力的程度。除了金融公司获得的收入外,他们的货币权力也反映在他们持有的资产价值上。图4.3通过显示股价与公司利润之间的关系,说明了资产积累的动态。正如它所表明的那样,在新自由主义时代,股票的市场价格增长速度远远快于公司每股利润的增长速度。这种分歧表明,股价本身已经成为金融积累的基础。此外,它还说明了新自由主义在多大程度上与资本主义发展的早期阶段决裂,因为这一比例超过了二十世纪任何其他时期,包括古典金融资本。

图4.3:1880-2008年标准普尔500指数公司的市盈率

来源:全球金融数据,WRDS,作者计算

至关重要的是,资产积累的成功从根本上取决于企业产生利润的能力。持有无法这样做的公司的股票不能作为投资者长期积累货币权力的基础。一个膨胀的股价,没有一个盈利的基础公司,是经典股票“泡沫”的定义。可以肯定的是,即使是盈利公司的股票也可能陷入泡沫。从理论上讲,无论哪种情况,最终的结果都是市场的“修正”,将股价降至“均衡”水平。我们经常看到这种情况发生,例如在20世纪90年代的“互联网”泡沫中。重要的一点是,投资者对未来积累的预期(如股价所反映的)与标的公司产生剩余价值的实际能力之间最终必然存在某种对应关系。

因此,虽然图表4.3显示,在新自由主义时期,市盈率总体上有所上升,因此股价和公司利润之间的差异也有所增加,但这绝不意味着两者之间的对应关系中断。相反,这表明股权资产已经以一种新的方式——即通过股价上涨——成为积累货币力量的基础。但这只能在这些公司保持盈利的预期下发生。同样,无利可图的公司的股价可能会上涨,因为预计这些公司在未来的某个时候会盈利。

因此,股票价格反映了对部分资本未来前景的猜测,而这些资本只能用利润来衡量。当然,并不能保证这些猜测是正确的:一些投资者总是会赌错,而另一些投资者则会得到回报。无论结果如何,都不能假设对股市的投资只是对“真实”投资的转移。货币资本的抽象性质意味着股票市场收益可以重新分配到任何具体的资本回路中,从而进入新的实物投资和新产品。此外,股票市场投资和固定资本投资绝不是相互排斥的:在整个新自由主义时期,企业投资保持在历史平均水平内(图4.7),而企业利润激增(图4.8),研发支出增加(图4.6)。

金融霸权不仅植根于公司股票价值的增长,还植根于股权所赋予的特定权力。股权日益重要,产生了一种新的所有权和控制权分离形式。当然,公司内部流动的资本仍由其经理控制。然而,与偿还后即不存在的贷款不同,股票使其所有者有权永久分享盈余。它们不是基于对工业资本家手中的货币资本的所有权要求,而是建立了对公司本身的所有权。这也赋予了股东对公司一定程度的控制权。因此,股权的集中以及这些大型资产流动性不足带来的长期主义倾向于使金融家更直接地投入生产。

然而,资产所有权的集中伴随着金融体系的碎片化。权力在一系列金融机构之间的分散是通过“市场金融”的出现实现的。传统上,贷款集中在银行的控制之下,银行是“货币资本的总经理”。因此,马克思认为货币资本家和银行家基本上是可以互换的。基于市场的金融是一种全新的金融中介模式,即资金从贷款人流向借款人的方式。在市场体系中,借款人可以直接从金融市场获得信贷,而无需通过银行。同样,储户可以通过非银行金融机构投资一系列金融工具,如股票和债券,作为银行存款的替代方案。

因此,随着市场金融的发展,越来越多的金融交易在一个被称为“去中介化”的过程中绕过了银行。20世纪70年代和80年代,去中介化的增加对银行构成了重大的竞争挑战。首先,货币市场共同基金的出现——由共同基金公司管理并投资于安全、短期债务证券的货币资本池——将储蓄从支票账户中抽走。由于Q条例对利息支付的限制不适用于这些基金,因此它们能够为投资者提供比银行更高的回报率。这推动了非银行金融机构的增长,特别是在20世纪70年代通货膨胀推动市场利率上升的情况下。沃尔克冲击进一步加剧了这些压力,使利率比Q规定水平高出整整10%。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。