Written by: imToken

Whether the United States has "invaded" Venezuela is a semantic judgment that directly determines a bet worth over ten million dollars.

You might find this a bit counterintuitive, as in the real world, the United States has indeed taken a series of measures against Venezuela, including military deployments and direct actions. In everyday language and media narratives, such actions are easily understood as "invasion."

However, the final settlement did not align with the expectations of some bettors—ultimately, Polymarket did not recognize the actions of the U.S. military as constituting "invasion" within its rules context, thereby negating the validity of the "Yes" option, which led to protests from bettors.

This is actually a not-so-new but highly representative controversy, which once again exposes a long-standing yet often overlooked structural issue in prediction markets: When it comes to complex real-world events, what justifies decentralized prediction markets, and who defines "facts"?

1. Frequent "Semantic Traps" in Prediction Markets

The reason it is said to be "not new" is that similar semantic disputes have occurred multiple times in prediction markets.

Indeed, such situations on Polymarket are not uncommon, especially in predictions surrounding political figures and international situations. The platform has repeatedly produced results that users perceive as "counterintuitive," with some predictions having almost no controversy in reality, yet getting caught in repeated appeals and reversals on-chain; while other events have final rulings that clearly deviate from the reality perceived by most users.

In more extreme cases, during the dispute resolution phase, the oracle mechanism allows token holders to participate in voting, leading to situations where certain topic-related events are "reversed by the voting power of major players"…

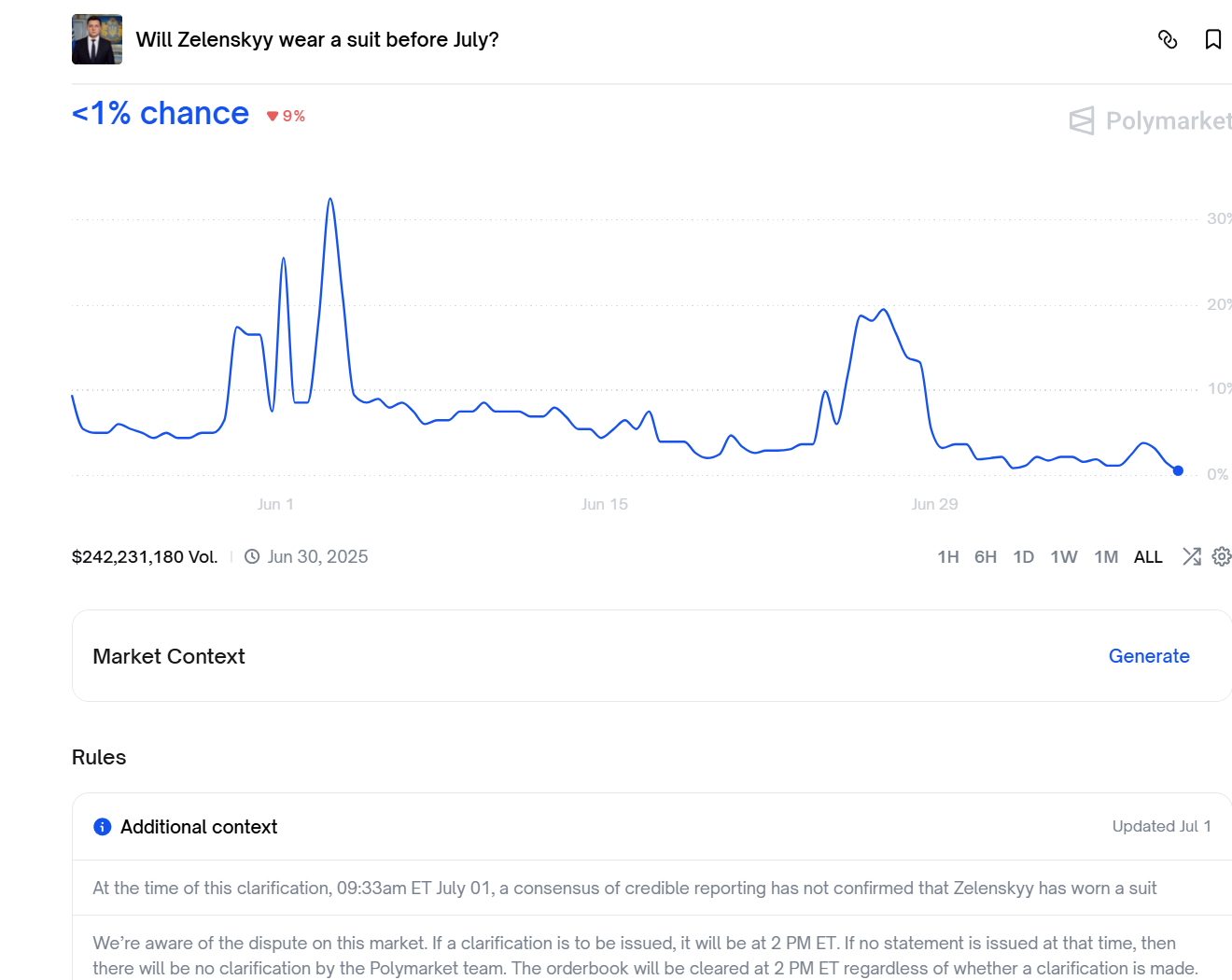

These controversies share a common point: they are often not technical issues, but rather social consensus issues. For example, a widely discussed case is whether Ukrainian President Zelensky "wore a suit" at a specific time:

In reality, Zelensky attended a public event in formal attire last June, and interpretations from BBC and designers all identified it as a suit. Logically, the result should have been settled, but on Polymarket, this seemingly clear fact evolved into a tug-of-war involving hundreds of millions of dollars.

During this period, the probabilities of Yes and No fluctuated wildly, with high-risk arbitrage behaviors occurring, and some individuals realized substantial floating profits in a short time, yet the final settlement remained unresolved for a long time.

The crux of the issue lies in Polymarket's reliance on the decentralized oracle UMA for result adjudication, and its operational mechanism allows holders to vote in dispute resolution, making it easy for certain topic-related events to be manipulated by major players.

More controversially, the platform does not deny that this mechanism can be exploited, yet insists that "rules are rules," refusing to adjust the adjudication logic post-factum, ultimately allowing large funds to overturn outcomes through the rules themselves.

Such cases provide a clear lens for understanding the institutional boundaries of prediction markets.

2. The Ineffective Boundaries of "Code is Law"

Objectively speaking, prediction markets are now seen as one of the most imaginative applications of blockchain, no longer just a small tool for "betting" or "predicting the future," but rather a front line for institutions, analysts, and even central banks to observe market sentiment (see further reading: "The Breaking Moment of 'Prediction Markets': ICE Enters, Hyperliquid Doubles Down, Why Are Giants Competing for 'Pricing Uncertainty'?").

But all of this has one prerequisite: the prediction question must be answerable with clarity.

It is important to know that blockchain systems are inherently good at handling deterministic issues—such as whether assets have arrived, whether states have changed, or whether conditions have been met. Once these results are written on-chain, there is almost no room for tampering.

However, what prediction markets often face are another type of object: whether a war has broken out, whether an election has concluded, or whether a certain political or military action constitutes a specific nature judgment. These questions do not naturally possess codability; they heavily rely on context, interpretation, and social consensus, rather than a single, verifiable objective signal.

For this reason, regardless of the oracle or adjudication mechanism used, subjectivity is almost unavoidable in the process of converting real-world events into settleable results.

This is why, in multiple disputes on Polymarket, the divergence between users and the platform does not lie in whether the facts exist, but in which interpretation of reality can be settled.

Ultimately, when this interpretive power cannot be fully formalized by code, the underlying logic of the grand vision of "code is law" inevitably encounters boundaries in the face of complex social semantics.

3. The "Last Mile" of Truth is Hard to Decentralize

In many decentralized narratives, "centralization" is often seen as a system flaw, but I believe that in the specific scenario of prediction markets, the opposite is true.

Because prediction markets do not eliminate adjudicative power; rather, they transfer adjudicative power from one location to another:

- Transaction and settlement phase: highly decentralized, automatically executed;

- Definition and interpretation phase: highly centralized, reliant on rules and adjudicators;

In other words, decentralization addresses the credibility of execution but cannot avoid the reality of concentrated interpretive power. This is why the concept of "code is law," which is highly attractive in the blockchain world, often appears powerless in prediction markets—because code cannot generate social consensus on its own; it can only faithfully execute established rules.

When the rules themselves cannot cover the full complexity of reality, adjudicative power will inevitably return to "humans." The difference lies in the fact that this adjudicative power no longer appears in an explicit arbitrator role but is hidden within the definition of questions, interpretation of rules, and adjudication processes.

Returning to the controversy on Polymarket, it does not imply that prediction markets have failed, nor does it mean that the decentralized narrative is a castle in the air. On the contrary, such controversies remind us to re-understand the applicable boundaries of prediction markets: they are very suitable for clear outcomes and well-defined data/events, yet are inherently not good at handling highly politicized, semantically ambiguous, and value-laden real-world issues.

From this perspective, what prediction markets have never resolved is "who is right or wrong," but rather how the market efficiently aggregates expectations under given rules. Therefore, once the rules themselves become the focus of controversy, the system will expose its institutional boundaries.

The latest controversy over whether Venezuela has been "invaded" essentially illustrates that when it comes to complex real-world events, decentralization does not mean the absence of adjudicators; rather, adjudicative power exists in a more concealed manner.

For ordinary users, what truly matters may not be whether prediction markets are "decentralized," but rather who has the power to define the issues when disputes arise? Who decides which version of reality can be settled? Are the rules clear and predictable enough?

In this sense, prediction markets are not only an experiment in collective intelligence but also a power struggle over "who has the right to define reality."

Understanding this allows us to find a balance point that is closer to certainty amid uncertain truths.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。