Author: Jing Yang (X:@unaiyang)

Reviewers: Colin Su, Grace Gui, NingNing, Owen Chen

Design: Alita Li

Abstract

The problem with China's real estate is not just a cash flow shortage, but rather a lack of transparency in a large number of existing assets, which are unmanageable, cash flows that cannot be verified, and unpredictable exits, making capital hesitant to enter the market. This article proposes a path of risk clearance, asset stratification, capital export, and institutional repair, forming a dual exit closed loop with REITs (exit assets) and equity (exit capability). Furthermore, the article argues that on-chain financing (RWA) for the continuation of unfinished buildings and revitalization of existing assets should not focus on moving properties onto the chain, but rather on creating executable institutional engineering for custody, allocation, disclosure, auditing, distribution, and default handling. At the same time, global tax information exchange systems like CRS are strengthening the penetration identification of cross-border funds and digital assets, so on-chain financing must treat tax and compliance as part of its product capabilities to truly form a replicable capital return mechanism.

01. Research Background and Problem Definition

Recently, the financing story of large models in the Hong Kong stock market has provided a very realistic reference for real estate clearance: financing is never just a pure mathematical problem, but rather a deterministic productization. Chinese large model companies represented by Zhipu and MiniMax have successively landed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and the market has given differentiated pricing with real money. Speaking of AI, behind it are different founder temperaments, investor structures, and narrative couplings: some are more academic or aligned with national strategy, while others are more globalized or aligned with dollar aesthetics, but the common point is that they package uncertain R&D investments into paths that the capital market can understand (technical barriers, commercialization rhythm, regulatory acceptability, and exit expectations). MiniMax's IPO raised approximately $619 million, and details such as the first-day surge (and the list of investors betting on whom) essentially emphasize one thing: capital is willing to pay for verifiable future cash flows and is also willing to pay for clear institutional exits.

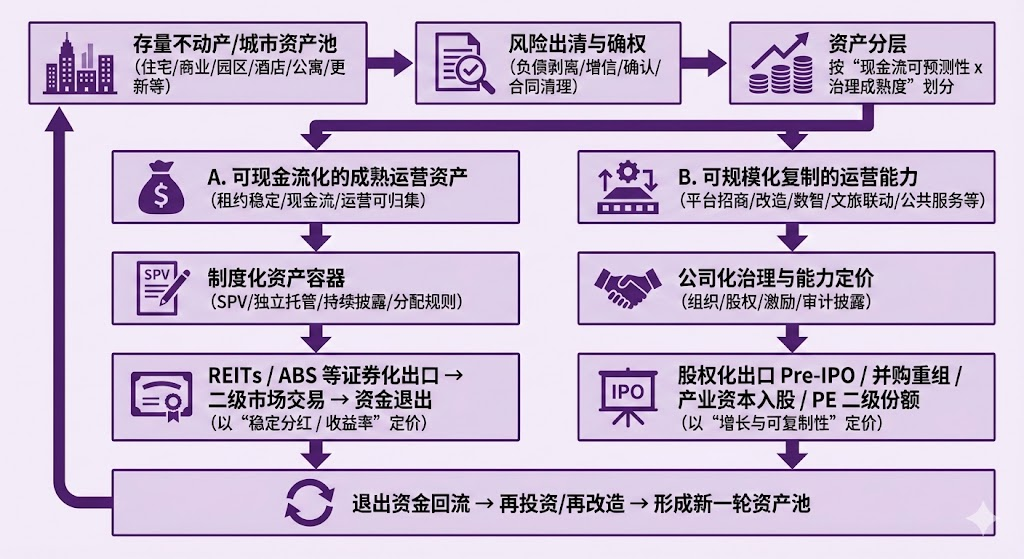

Turning this lens back to China's real estate, the difficulty of unfinished buildings is not just an issue with the assets themselves, but rather the absence of a systematic chain that allows funds to enter, stay in projects, and ultimately exit with peace of mind: ownership transparency, closed funding, milestone payments, continuous disclosure, independent custody, default handling, and exit mechanisms. If on-chain financing is to become new finance, its value lies not in moving properties onto the chain, but in making the aforementioned chain a programmable, auditable, and accountable financial infrastructure: using project-level SPVs to clarify boundaries of rights and responsibilities; using regulatory/custodial accounts + on-chain certificates to first pool funds and then allocate them; using engineering milestones (acceptance/audit reports/third-party supervision) to trigger phased payments, avoiding fund misappropriation; and using on-chain cash flow dashboards to turn lease agreements, collection rates, vacancy rates, operating costs, and CapEx into continuously updated data products. In this way, the so-called financing return is not about injecting water out of thin air, but about addressing the most important concern of social capital: bringing projects back from storytelling to delivery and cash flow. Once delivery certainty increases, funds may shift from waiting to taking over/continuing construction/mergers and acquisitions/securitization exits.

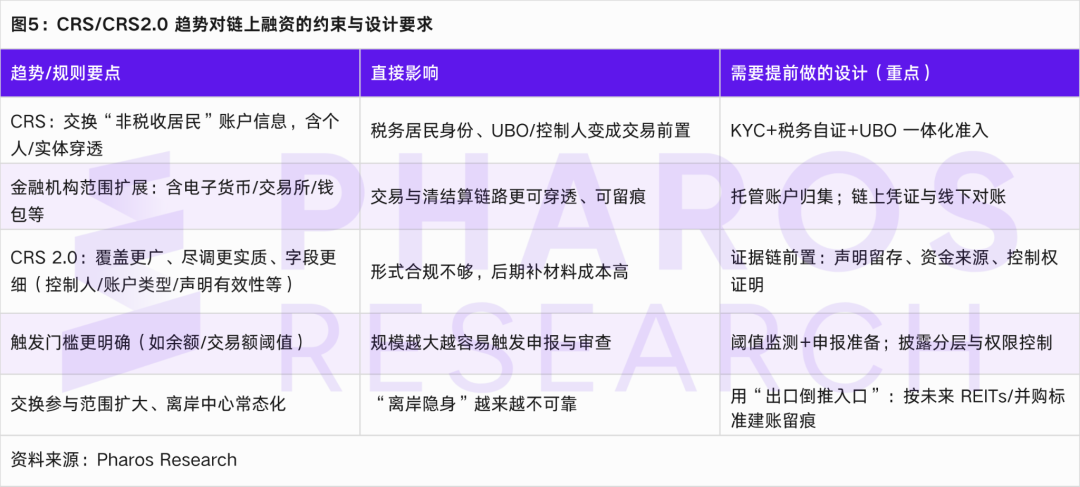

However, it must be emphasized that entering the era of on-chain financing, the most easily underestimated factor is not technology, but the rigid constraints of tax and information transparency, especially frameworks like CRS for automatic information exchange. The logic of CRS is simple: tax authorities in various countries want to grasp the account information (balances, interest, dividends, etc.) of their tax residents in foreign financial institutions; it is not a question of whether it will come, but rather that it is already here and will continue to expand. More critically, the OECD has recently included digital finance in its governance vision: on one hand, it has launched CARF (an information reporting and exchange framework for crypto asset service providers), and on the other hand, it is promoting revisions to CRS (commonly referred to in the industry as CRS 2.0), which includes electronic money, CBDCs, etc., and strengthens due diligence and data fields, aiming to close the transparency gap in the digital asset era; the OECD has also clearly stated that the first exchange expectations for CARF and the revised CRS will begin in 2027. Taking Hong Kong as an example, the official consultation document proposes that CARF-related legislation aims to be completed by 2026, with service providers collecting information starting in 2027 and exchanging it with partner jurisdictions in 2028; the revised CRS is planned to be implemented starting in 2029 (subject to final legislation). This means that on-chain financing will not make funds more hidden; rather, it will make compliance a part of financing capability, especially when targeting foreign funds, using stablecoins for settlement, or reaching investors through exchanges/custodians/wallets, where tax resident identification, controlling persons penetration, KYC/AML, and reporting data preparation in the context of CRS/CARF will become prerequisites for whether transactions can be established.

The conclusion is straightforward: on-chain financing may indeed become a new channel for the refinancing of unfinished buildings and existing assets, but it cannot solve the fantasy of where the money comes from; rather, it addresses why money dares to come, how it will not be misappropriated after it arrives, and how it can exit in the future through institutional engineering. As for CRS, it determines that what you need to do is not to bypass transparency, but to make compliance a product capability in the era of transparency (qualified investor access, tax information collection, standardized custody and disclosure, auditable fund flows and distribution rules), so that on-chain financing can transform from a concept into a replicable capital return mechanism.

02. Four-Stage Recovery Mechanism

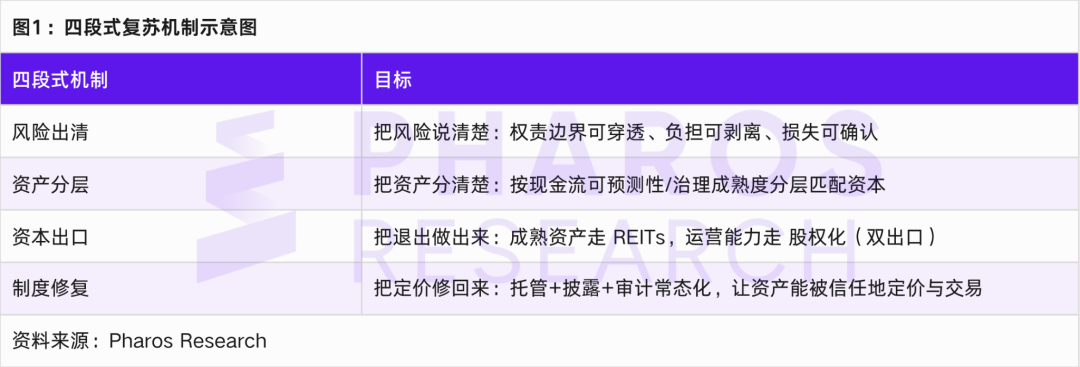

The four-stage mechanism proposed in this article does not pursue a slogan-like stabilization, but rather breaks down recovery into actionable institutional actions.

The first stage is risk clearance. Clearance is not about discarding assets, but rather about splitting, restructuring, and confirming losses from sources of risk such as bad debts, unfinished projects, illegal guarantees, and hidden debts through legal and financial tools, forming an accountable and assessable asset package. The Pangu incident provides a highly symbolic picture: when a landmark asset was packaged and listed for judicial auction with a starting price of approximately 5.94 billion yuan but received no bids, this indicates that in the absence of sufficient transparency in cash flow disclosure and operational certainty, landmarks cannot automatically be monetized. The key to clearance lies not in the auction itself, but in the asset governance prior to the auction: ownership transparency, burden separation, lease authenticity, operational cost structure, cash flow pooling, and regulatory account arrangements.

The second stage is asset stratification. Real estate assets are not a single species: residential development, commercial office buildings, hotels, parks, public rental housing, urban renewal projects correspond to different cash flow forms and capital preferences. The purpose of stratification is to upgrade assets from "divided by use" to "divided by cash flow predictability and governance maturity," matching exit tools to underlying assets.

The third stage is capital export. This article emphasizes a dual exit structure: mature cash flow assets go through REITs, while platform operational capabilities and urban service capabilities go through equity (Pre-IPO, mergers and acquisitions, private equity secondary share trading, etc.). The pilot documents for commercial real estate REITs clearly outline requirements for product forms, due diligence, and operational management responsibilities, indicating that exit tools for commercial real estate are being institutionalized; meanwhile, the expanded industry scope list for infrastructure REITs has broadened the range of reportable assets, indicating that the pool of securitizable assets is expanding. The combination of the two shifts the constraints of the export mechanism from "whether there are products" to "whether the assets meet institutional disclosure and operational standards." At the same time, the regular issuance of infrastructure REITs also provides policy support for "regular issuance."

The fourth stage is institutional repair. The core indicator of institutional repair is not the rebound of housing prices, but the restoration of asset pricing: the market can price assets based on disclosure, governance, custody, and cash flow quality, and the exit paths are predictable, replicable, and regulatory. This step determines whether the recovery is a one-time rebound or the start of a new cycle.

03. Dual Exit Structure

In mature markets, the exit from commercial real estate does not rely on selling buildings for profit, but rather on operational cash flow and securitization exits. The practice of public REITs in infrastructure in China over the past few years has already trained the chain from assets, cash flow, disclosure, custody to distribution at the institutional level. The introduction of commercial real estate REITs has brought typical urban operational assets such as office buildings, commercial complexes, and hotels into the realm of institutionalized exits: the pilot documents define commercial real estate REITs as closed-end public funds that obtain stable cash flow through holding commercial real estate and distribute profits to holders, emphasizing the active operational management responsibility of fund managers. This means that the key to whether REITs can be established in the future lies not in whether the assets are luxurious, but in whether the assets can stably generate cash flow like infrastructure and be continuously disclosed and governed.

REITs buy predictable cash flows, while equity buys replicable growth capabilities. When you place real estate and urban assets into this framework, many seemingly unavoidable contradictions will be automatically clarified.

Figure 2: Diagram of the chain from assets, cash flow, disclosure, custody to distribution

Source: Pharos Research

First, REITs are inherently a system for turning assets into income products. In mature markets, the core pricing method of REITs is distribution and yield: investors do not come to bet on how much a building can appreciate, but rather to buy how much cash flow it can stably generate in the coming years and whether it can continue to distribute. Therefore, REITs have a natural preference for underlying assets: leases must be relatively stable, occupancy rates must be resilient, cash flows must be collectible, cost structures must be explainable, and disclosures must be continuous. In other words, REITs essentially turn the operating cash flow of real estate into a securitizable income right that is close to infrastructure. What they excel at solving is: once a building or a group of buildings is operational, how can I move it off the balance sheet, allow funds to exit, keep the assets operational, and recycle capital? Thus, when you say REITs are suitable for exiting cash-flow-generating assets, the underlying logic is that the institutional requirements of REITs and the pricing methods of investors determine that they are more suited to take on assets after operational stability, rather than those with strong development risks, high uncertainty, or driven by strong narratives.

Second, the value of many urban assets does not lie within the buildings themselves, but in the ability to operate them. In reality, the differentiation of assets such as office buildings, commercial complexes, parks, and hotels often does not come from the location itself, but from operational capabilities: leasing ability determines tenant structure, tenant structure determines cash flow stability; energy efficiency upgrades and project management determine cost curves; digital management determines collection rates and risk visualization; cultural tourism and commercial linkage, public service provision determine foot traffic and per square meter efficiency. More critically, these capabilities can often be replicated across projects: running one building well is one thing, but replicating the methodology, team, and systems to run ten buildings, an area, or even a city is another. The capital market's pricing method for such things is naturally more like equity: it looks not only at current profits but also at growth curves, replicability, and whether the organization and systems can be scaled. Thus, the equity path (Pre-IPO, mergers and acquisitions, industrial capital participation, private share transfers) becomes a more natural exit, as it can sell, integrate, and premium the future expandable capabilities as core assets.

Third, why not reverse it: use REITs for exit capability and equity for asset exit? Because the constraints of the tools are different. The structure of REITs makes it more like a profit distribution machine: it requires sustainable underlying cash flows, sustainable disclosures, and minimal volatility, and the market tends to price it based on yield, which naturally lowers the weight of growth stories. If you stuff an operational platform company into a REIT, investors will still ask: Is your income stable rent? Is your profit volatility due to expansion? Does your expansion bring development risks? Once the answers lean towards growth and expansion, the pricing framework of REITs becomes uncomfortable. Conversely, using equity to take on a bunch of mature assets is not impossible, but equity investors often demand higher returns and stronger growth expectations; yet the most certain value of a bunch of mature assets is precisely the stable but limited growth cash flow. Such assets are more likely to achieve lower capital costs and a broader investor base through REITs (or similar securitization), which also aligns better with regulatory and disclosure logic.

Fourth, this dual exit is not fragmented but can feed into each other. The strongest form is often: the platform company equity-izes its operational capabilities (attracting industrial capital, mergers and integrations, scaling up), while continuously injecting mature assets into REITs (forming an asset securitization exit). The platform company earns long-term returns through management fees, operational service fees, and asset recycling. In this way, REITs provide asset-level exits and capital returns, while equity-ization offers capability-level expansion and valuation premiums, together transitioning urban assets from development and selling buildings to operation, securitization, and reinvestment in a capital cycle.

04. Case Study 1: What the Discounted Judicial Auction Reveals

The significance of the Pangu incident lies not in the gossip but in the institutional signal: when a landmark asset can be auctioned, can be packaged, and can be publicly listed, yet still frequently fails to sell at a discount, it indicates that the market does not lack assets but lacks credible assets. In the absence of systematic information disclosure and cash flow pooling mechanisms, investors face a set of impenetrable questions: What is its real rent? Is the lease stable? What is the property and tax cost structure? Are there historical burdens of rights? Is cash flow pooled into a regulated account? What is the future capital exit path?

Pangu is not an isolated case. It is a typical form of asset pricing failure: the physical form of the asset is very strong, but its financial form is very weak. In other words, what it lacks is not location but institutionalized financial tradability. This also explains why the recovery of real estate cannot rely solely on interest rate cuts, deregulation, and emotional repair: if assets remain impenetrable, unmanageable, and unsustainably disclosable, capital will not provide stable pricing.

05. Case Study 2: How Overseas Golden Visas Institutionalize Real Estate

In contrast to Pangu, the degree of institutionalization of overseas real estate and identity projects is notable. Taking the Greek Golden Visa as an example, its policy design does not treat real estate as a speculative target but rather as a compliance ticket: investment thresholds are stratified by region, with specific requirements for single properties and area, and restrictions on usage (especially short-term rentals). Public legal and institutional interpretations show that the investment threshold for the Greek Golden Visa has increased to €800,000 or €400,000 in some areas, while retaining a €250,000 path related to restoration/use conversion. At the same time, short-term rental restrictions (such as prohibiting Airbnb-style short-term rentals) on properties obtained through the Golden Visa, with violations potentially facing fines or licensing risks, have also appeared in interpretations by several professional institutions. Such projects are often simplified in market communication as buying a house for identity, but from an institutional engineering perspective, they resemble a packaged product of assets, compliance, usage, and rights:

What you are buying is not just a house, but a comprehensive institutional arrangement with clear ownership, defined thresholds, controlled usage, and renewable rights. Compared to the information opacity, unstable governance, and uncertain exits of some domestic existing assets, overseas projects have a more financialized pricing of risks. The implication for Chinese real estate is that true recovery is not about making assets expensive again, but about making assets trustworthily priced again.

06. The Focus of Institutional Engineering

The second is independent custody and cash flow pooling. Whether it is REITs, ABS, or equity exits, what investors ultimately buy is the credibility of cash flows. Custody arrangements must ensure that cash flows are pooled first and then distributed, supporting regulatory penetration verification. This is where financial technology excels: account systems, payment clearing, permission control, risk control strategies, and audit trails.

The third is cash flow dashboards and continuous disclosure. The difficulty in transacting Pangu-style assets fundamentally lies in the inability to continuously explain the assets. Dashboards are not PPTs but turn leases, collection rates, vacancy rates, energy costs, maintenance capital expenditures (CapEx), taxes, and distribution rules into sustainably updated data products, shifting assets from story-driven to data-driven.

When these three elements are established, the so-called good assets can be defined: not by luxurious decoration, but by predictable cash flows, sustainable disclosures, and verifiable governance.

07. RWA On-Chain

In a longer-term capital cycle, RWA on-chain can become an accelerator for the dual exit structure, but the premise is to place it back in the context of institutional engineering rather than marketing. The BIS/CPMI describes tokenization as generating and recording digital representations of traditional assets on programmable platforms, emphasizing that it may reshape the entire lifecycle process of assets through platform intermediaries, but requires sound governance and risk management. The FSB also points out that tokenization may change the structure of traditional markets and the roles of participants, necessitating attention to financial stability implications. IOSCO's report further discusses the risks, market development barriers, and regulatory considerations of tokenized financial assets from a securities regulatory perspective.

Translating these frameworks to real estate and urban assets, the correct approach to RWA is:

(1) What is represented on-chain is not the house, but the rights and cash flow distribution rights of the SPV;

(2) What is recorded on-chain is not the price, but verifiable certificates of cash flow and compliance status;

(3) What is traded on-chain is not unregulated tokens, but constrained shares that are subject to transparent custody, auditable disclosures, and controllable transfers.

In terms of engineering implementation, this article suggests adopting a "permissioned chain/consortium chain + regulatory readable interface" approach: hashing key fields of ownership and contracts on-chain, with original materials held by custodians and auditors; cash flow pooling within a regulated account system, mapping results to the chain through verifiable reconciliations; and making distribution and restrictive clauses (such as qualified investor, lock-up periods, usage restrictions) into executable rules through smart contracts. In this way, the value of the chain is not to eliminate intermediaries but to make intermediary actions verifiable, transferring institutional credit from paper to an auditable operational system.

When the goal of RWA is defined as institutionally credible digitalization, it naturally serves the dual exit structure: mature assets can use the chain to enhance disclosure and clearing efficiency within the REITs/ABS system; the equity exit of operational platforms can use the chain to standardize due diligence packages for underlying assets and operational data, reducing information asymmetry costs and enhancing merger and financing efficiency.

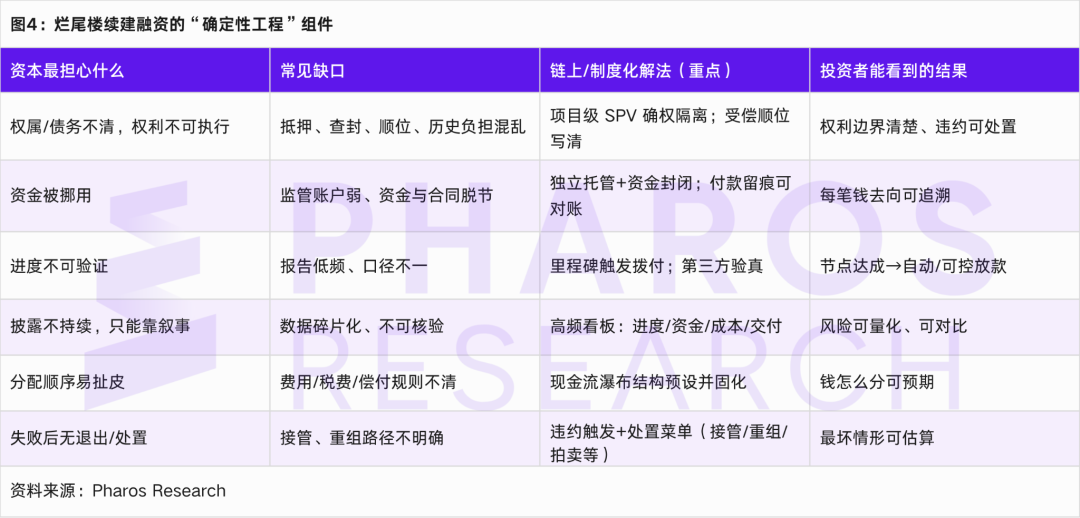

7.1 From Financing Narrative to Certainty Engineering

In recent years, the capital market's patience for "narratives" has noticeably shortened, while the pricing for certainty has significantly increased. The financing and listing stories of large model companies are valid not because they present a grander future, but because they break down the future into verifiable paths: when will delivery occur, how will it be commercialized, how will disclosures be made, and where is the exit mechanism? Returning this to unfinished buildings and stalled projects, the difficulty in financing is not merely due to interest rates or emotions, but because once funds enter projects, there is a lack of an executable governance structure to answer three very practical questions: why does the money dare to come in, how is it ensured that it will not be misappropriated after it arrives, and how to handle and exit if progress is not smooth.

On-chain financing in the context of real estate is often misunderstood as merely putting assets on-chain. But a more accurate positioning is that it is a method of engineering certainty, that is, institutionalizing the most critical and easily questioned aspects of project governance, such as ownership boundaries, fund pooling, milestone payments, continuous disclosures, distribution sequences, and default handling, and making key records auditable, traceable, and accountable. To avoid conceptual expressions, Figure 4 directly correlates "what unfinished building financing fears most" with "what on-chain financing should do."

In the above structure, whether on-chain financing can help the capital return of unfinished buildings is not primarily about how cool the tokens are made at the issuance end, but whether the project end has truly completed certainty production: funds are managed in a closed manner, payments are tied to engineering milestones, disclosures can continuously reconcile, and distribution and disposal rules are executable. As long as this institutional engineering can operate, financing is no longer a life-saving blood transfusion but more like a replicable project financial product: initial funds are used for continuation to achieve delivery, delivery and operation generate cash flow, and cash flow is then used to complete payments and profit distributions through an established waterfall structure, ultimately creating preconditions for subsequent REITs, ABS, mergers, or equity exits.

7.2 CRS and On-Chain Financing in the Era of Tax Transparency

A very realistic change is that the logic of CRS has long expanded from traditional bank account reporting to a broader penetration of financial intermediaries. In the CRS materials you provided, the financial institutions defined by CRS not only include deposit institutions, custodial institutions, investment institutions, and specific insurance companies, but also clearly include a category of "new financial institutions," covering electronic money providers, crypto asset investment institutions, crypto asset exchanges, and digital wallet service providers; this means that once the digital financial link has financial intermediary attributes, it becomes increasingly difficult to remain outside the information exchange and penetration identification. At the same time, the materials also emphasize that CRS 2.0, compared to 1.0, aims to expand coverage, strengthen due diligence, increase reporting fields, and include digital assets, and that clearer reporting trigger thresholds and stronger transaction caliber requirements have emerged in jurisdictions like Hong Kong.

Within this framework, the core point that the CRS section of the paper aims to express should be clearer and more robust: on-chain financing will not inherently lower transparency requirements; rather, under the trend of global tax information exchange and digital financial penetration identification, compliance will shift from backend management to a prerequisite for transaction establishment. In other words, for on-chain financing to become an institutional tool for the continuation of unfinished buildings and the revitalization of existing assets, it must simultaneously provide two types of certainty: one is project certainty, that is, how funds are managed in a closed manner, how they are paid according to milestones, how disclosures are made continuously to form predictable cash flows; the second is compliance certainty, that is, clear tax identities and control chains, explainable fund paths, auditable records, and controllable and exportable disclosures. Without either type of certainty, funds will either not come or, if they do, it will be difficult to form a replicable scalable supply.

08. Conclusion and Trend Outlook

This article argues that the key variable for the recovery of real estate is not a rebound in prices, but whether assets can be re-priced with trust. The current issue is not just cash flow tightness, but also the difficulty in penetrating the ownership and burdens of a large number of existing assets, the challenges in closing funds, verifying cash flows, sustaining disclosures, and predicting exits. As long as these fundamental conditions are lacking, assets appear more like risk exposures rather than investable targets in the eyes of capital, and the market can only rely on emotions and policies to form short-term trades, making it difficult to restore stable pricing.

Based on this, the conclusions of this article can be summarized in three points. First, the essence of clearing is to turn assets into rules: clarifying rights and responsibilities through project-level SPVs, achieving closed fund pooling with independent custody and regulatory accounts, triggering payments through engineering milestones to form auditable trails, and supporting continuous disclosure and default handling mechanisms, allowing funds to enter, stay, and exit confidently. Second, recovery requires dual exits rather than a single rescue: mature cash flow assets are more suitable for exit through REITs/securitization, while operational and urban service capabilities are more suitable for exit through equity paths (mergers and integrations, pre-IPO, private share transfers, etc.). Separating the pricing and exit of assets and capabilities can create a cycle of capital return and reinvestment. Third, the value of RWA lies not in moving real estate on-chain, but in making custody, payments, disclosures, audits, distributions, and disposals into executable institutional engineering: what is carried on-chain are the rights of SPVs and cash flow distribution rights, and what is recorded on-chain are verifiable certificates of reconciliation and compliance status, thereby reducing information asymmetry and misappropriation risks. At the same time, trends in tax information exchange such as CRS/CARF strengthen the penetration identification of cross-border funds and digital assets, meaning compliance is no longer a backend cost but a prerequisite for the establishment of transactions.

Looking ahead to the next few years, the industry will shift from asset-driven to governance-driven differentiation. First, the supply of REITs and the range of assets may continue to expand, but thresholds will increasingly reflect governance and disclosure standards; exits will no longer be scarce, but meeting standards will be. Second, the valuation language of commercial real estate will more quickly return to cash flow: lease quality, collection rates, vacancy rates, operating costs, and CapEx will become core pricing parameters. Third, mergers and integrations and platform operations will become more important, with capital more willing to pay for replicable operational systems. Fourth, RWA is more likely to move towards a path of licensing, custody, and auditing, prioritized for project financing closed loops and the refinancing of existing assets. Fifth, cross-border funds will consider tax identities, beneficial ownership transparency, and auditable records as entry thresholds, promoting compliance capabilities as part of financing capabilities. Overall, the institutional transition of real estate ultimately depends on whether governance can be turned into a standardized, replicable, and regulatory-compliant asset operating system.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。