Author: Andy Hall, Professor at Stanford Business School and Hoover Institution

Translation: Felix, PANews (This article has been edited)

Imagine a scenario: It’s October 2028, and Vance and Mark Cuban are neck and neck in the presidential election. Suddenly, Vance's support in the prediction market begins to soar. CNN, in partnership with Kalshi, provides round-the-clock coverage of prediction market prices.

Meanwhile, no one knows the initial reason for the price surge. Democrats insist the market has been "manipulated." They point out that a large number of suspicious trades have pushed the market to favor Vance without any new polls or other obvious reasons.

At the same time, The New York Times publishes a report claiming that traders backed by the Saudi Arabian sovereign wealth fund have placed large bets in the election market to ensure favorable coverage of Vance by CNN. Republicans argue that the prices are reasonable, noting that there is no evidence that the price surge would affect the election outcome, and accuse Democrats of trying to suppress free speech and censor truthful information about the election. The truth remains difficult to ascertain.

This article will explain why such a scenario is highly likely to occur in the coming years—despite the rarity of successful manipulation of prediction markets and the almost nonexistent evidence that they influence voter behavior.

Attempts to manipulate these markets are inevitable, and when manipulation occurs, the political impact may far exceed the direct effects on election outcomes. In an environment that is quick to interpret any anomaly as a conspiracy, even a brief distortion can trigger accusations of foreign interference, corruption, or elite collusion. Panic, blame, and a loss of trust may overshadow the actual impact of the initial actions.

However, abandoning prediction markets would be a mistake. As traditional polling becomes increasingly fragile in an AI-saturated environment—characterized by extremely low response rates and pollsters struggling to distinguish between AI responses and real human respondents—prediction markets provide a useful supplementary signal that integrates dispersed information and carries real financial incentives.

The challenge lies in governance: building a system that maintains the informational value of prediction markets while reducing abuse. This may mean ensuring that broadcasters focus on reporting those markets that are harder to manipulate and more active, encouraging platforms to monitor for signs of collusive manipulation, and shifting the interpretation of market fluctuations to view them with humility rather than panic. If this can be achieved, prediction markets could evolve into a more robust and transparent component of the political information ecosystem: one that helps the public understand elections rather than becoming a vehicle for generating distrust.

Learning from History: Beware of Attempts to Manipulate the Market

"Now everyone is watching the betting markets. Their fluctuations are fervently followed by ordinary voters who cannot personally gauge the direction of public sentiment and can only blindly rely on the opinions of those who bet hundreds of thousands of dollars in every election." — The Washington Post, November 5, 1905.

In the 1916 presidential election, Charles Evans Hughes led Woodrow Wilson in the New York betting market. Notably, during that era of American politics, the news media frequently reported on betting markets. Due to these reports, the shadow of market manipulation lingered. In 1916, Democrats, not wanting to be seen as trailing, claimed that the betting market was "manipulated," and the media reported on this.

The potential threat of manipulating election outcomes has never disappeared. On the morning of October 23, 2012, during the Barack Obama and Mitt Romney campaign, a trader placed a large order buying Romney shares on InTrade, causing his price to surge about 8 points, from just below 41 cents to nearly 49 cents—suggesting a near tie in the campaign if one believed the price. However, the price quickly retracted, and the media paid little attention. The identity of the would-be manipulator was never confirmed.

However, sometimes you even see individuals openly articulating their logic for attempting to manipulate the market. A 2004 study documented a case of deliberate market manipulation in the 1999 Berlin state election. The authors cited a real email sent by a local party office urging members to bet on the prediction market:

"The Daily Mirror (one of Germany's largest newspapers) publishes a political stock market (PSM) every day, and the current trading price for the Free Democratic Party (FDP) is 4.23%. You can check the PSM online at http://berlin.wahlstreet.de. Many citizens do not see the PSM as a game but rather as a reflection of public opinion. Therefore, it is important for the FDP's price to rise in the last few days. Like any exchange, price levels depend on demand. Please participate in the PSM and buy contracts for the FDP. Ultimately, we all firmly believe in our party's success."

These concerns resurfaced in 2024. On the eve of the election, The Wall Street Journal published an article questioning whether the large bets on Trump in Polymarket (which seemed to far exceed his polling support) were the result of improper influence: "Large bets on Trump may not be malicious. Some observers believe this could simply be a big gambler who is confident Trump will win and wants to make a profit. However, others believe these bets are a form of influence activity aimed at generating buzz for the former president on social media."

The scrutiny in 2024 is particularly intriguing as it raises concerns about foreign influence. The results indicated that the bets driving up Polymarket prices came from a French investor—though speculations existed, there was little reason to believe this was manipulation. In fact, this investor commissioned private polling and seemed focused on making money rather than manipulating the market.

This history reveals two themes. First, cyber attacks are common and are likely to occur in the future. Second, even if attacks do not work, some individuals can still incite fear.

How Much Impact Do These Attacks Have?

Whether these actions influence voter behavior depends on two factors: whether manipulation can effectively impact market prices, and whether changes in market prices affect voter behavior.

Let’s first explore why manipulating the market (if it can be done) would help you achieve political goals: because it is not as obvious as people might think.

Here are two ways prediction markets might influence election outcomes.

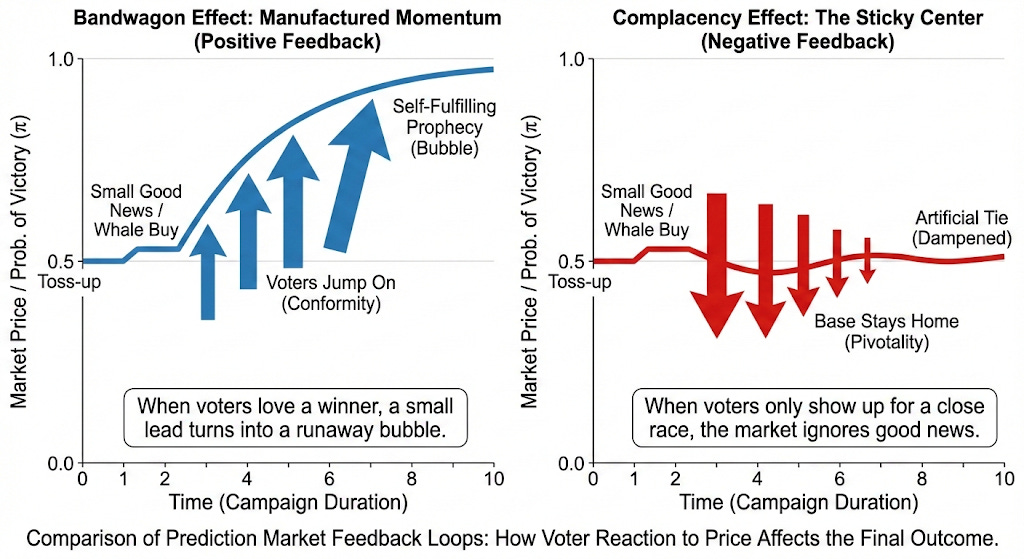

Herding Effect

The herding effect refers to voters' tendency to support candidates who appear likely to win, whether out of a desire to conform, the satisfaction of supporting a winner, or the belief that market odds reflect a candidate's quality.

If popularity helps a candidate gain more support, then broadcasting prediction market prices in the news creates an incentive to push those prices higher. Manipulators may attempt to raise the odds of their favored candidate, hoping to trigger a feedback loop: market price rises → voters perceive momentum → voters shift support → price rises again.

In the case of Vance-Cuban, the manipulator's bet is that making Vance appear stronger will help him actually win.

Complacency Effect

On the other hand, if the candidate that voters support is far ahead, they may choose not to vote. But if the race is tight, or their favored candidate seems to be losing, they may be more motivated to vote. In this case, widely disseminated prediction market prices create market pressure to keep the odds close to fifty-fifty. Once the market begins to favor one candidate, traders will know that the supporters of that candidate are starting to lose enthusiasm, thus pulling the price down.

This also facilitates market manipulation. A leading candidate who fears their supporters are too optimistic may quietly buy shares of their opponent to tighten the market and suggest that the competition is fiercer. Conversely, supporters of a trailing candidate may further depress their stock price to entice members of the opposing camp to believe victory is assured and abstain from voting. In this scenario, the market becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: the signals intended to reflect expectations instead undermine those expectations.

Despite significant controversy, some argue that Brexit is an example of this phenomenon. As noted in a report by the London School of Economics: "It is well known that polls can affect turnout and voting behavior, especially when one side appears to be winning. It seems that more supporters of remaining in the EU chose the easier option of not voting, possibly because they believed that remaining would win."

Voters Are Not Very Concerned About the Intensity of the Election

But the problem is that even if there are herding or complacency effects, existing evidence suggests their impact is usually small. U.S. elections are quite stable—primarily driven by partisan positions and fundamental factors like the economy—so if voters react strongly to claims about who is leading, the election results appear more chaotic. Moreover, when researchers attempt to directly alter people's perceptions of the competitiveness or significance of an election, the behavioral impacts are consistently limited.

An example of the current understanding of the theory that "the closer the race, the higher the turnout" is the study by Enos and Fowler on a Massachusetts state legislative election that actually ended in a tie. In a rerun of the election, they randomly informed some voters that the previous election in their district was decided by a single vote. Even with this extreme approach, the impact on turnout was negligible.

Similarly, Gerber et al. showed voters different polling results in large-scale field experiments. People updated their perceptions of the competitiveness of the election, but turnout changed very little. A study on a Swiss referendum found that this effect was slightly larger but still very limited: in this case, widely publicized close polls seemed to slightly increase turnout, but only by a few percentage points.

It is possible that at certain times, signals of a competitive election may indeed prompt some voters to change their minds, but this effect may be minimal. This does not mean that concerns about election fraud should be dismissed; rather, attention should be focused on the subtle influences in closely contested elections, rather than distorting factors that turn competitive elections into one-sided outcomes.

Manipulating the Market Is Both Difficult and Expensive

This leads to the second question: how difficult is it to manipulate prediction market prices?

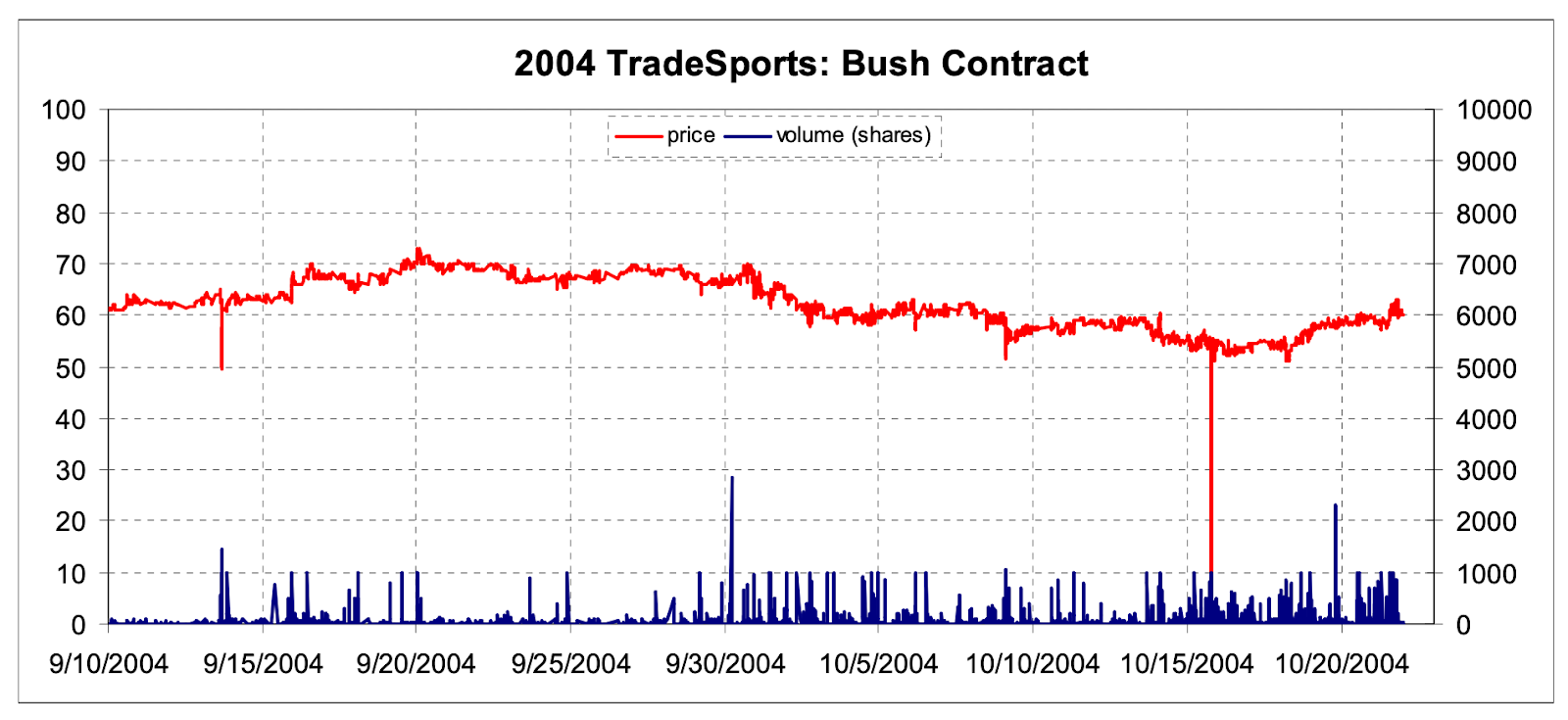

Rhode and Strumpf's study of the Iowa electronic market during the 2000 election found that attempts at manipulation are costly and difficult to sustain. In a typical case, a trader repeatedly placed oversized buy orders in an attempt to push the price up for their favored candidate. Each push briefly altered the odds, but was quickly arbitraged away by other traders, bringing the price back to normal levels. The manipulator invested heavily but incurred significant losses, while the market demonstrated strong mean reversion and resilience.

This is crucial in the hypothetical case of Vance and Cuban. Manipulating the presidential election market in October would require substantial funds, and many traders would be waiting to sell once prices surged. Such small fluctuations might last until it aired on CNN, but by the time CNN anchor Anderson Cooper began discussing it, the price might have already returned to its original level.

However, the situation changes when market liquidity is low. Researchers have demonstrated that in low liquidity environments, long-term prices can be manipulated: no one can prevent such manipulation.

Recommendations

While there may be evidence suggesting that manipulation of major election markets is unlikely to have significant effects, this does not mean inaction is acceptable. In a new world where prediction markets merge with social media and cable news, the impact of price manipulation may be greater than ever. Even if the effects of price manipulation are minimal, such concerns could influence the collective perception of the political system's fairness. How should this issue be addressed?

For Broadcasters:

Implement liquidity thresholds. CNN and other news organizations should focus on reporting prediction market prices for actively traded markets when covering elections and other political events, as these prices are more likely to reflect accurate expectations and have higher manipulation costs; they should avoid reporting prices from illiquid markets, as these prices are less accurate and have lower manipulation costs.

Incorporate other election expectation signals. News organizations should also closely monitor polls and other election expectation indicators. Although these indicators have their own flaws, they are less susceptible to strategic manipulation. If significant discrepancies are found between market prices and other signals, news organizations should seek evidence of manipulation.

For Prediction Markets:

Establish monitoring capabilities. Create systems and personnel capable of detecting deceptive trading, false trades, sudden spikes in unilateral trading volume, and collusive account activities. Companies like Kalshi and Polymarket may already possess some of these capabilities, but if they wish to be seen as responsible platforms, they should invest more resources.

Consider intervention measures in the event of severe and unexplained price fluctuations. This includes setting up simple circuit breakers in illiquid markets to respond to sudden price changes, as well as pausing trading and subsequently conducting a call auction to re-establish prices when price trends appear abnormal.

When reporting price indicators, consider how to enhance their resistance to manipulation. For prices displayed on television, use time-weighted or volume-weighted prices.

Continuously improve trading transparency. Transparency is crucial: publish indicators of liquidity, concentration, and unusual trading patterns (without revealing personal identities) so that journalists and the public can understand whether price fluctuations reflect real information or order book noise. Large markets like Kalshi and Polymarket have already shown their order books, but more detailed indicators and user-friendly dashboards would be very helpful.

For Policymakers:

Combat market manipulation. The first step is to clearly state that any attempts to manipulate election prediction market prices (to influence public opinion or media coverage) fall under existing anti-manipulation regulations. Regulatory agencies can act quickly when unexplained large price fluctuations occur on the eve of an election.

Regulate domestic and foreign political influences on the market. Given that election markets are highly susceptible to foreign influence and campaign finance issues, policymakers should consider two safeguards:

(1) Monitor foreign manipulation by tracking the nationality of traders, thanks to existing U.S. "KYC" laws, which are crucial for the operation of prediction markets.

(2) Develop disclosure rules or bans regarding campaign activities, political action committees (PACs), and senior political staff. If expenditures aimed at manipulating prices fall under undisclosed political spending, regulatory agencies should treat them as political expenditures.

Conclusion

Prediction markets can clarify rather than complicate elections, provided these markets are established responsibly. The collaboration between CNN and Kalshi signals that future market signals will become part of the political information environment alongside polls, models, and reports. This presents a genuine opportunity: in a world overwhelmed by AI, there is a need for tools that can extract dispersed information without distortion. However, this prospect depends on good governance, including liquidity standards, regulation, transparency, and a more cautious interpretation of market dynamics. If these aspects are handled well, prediction markets can enhance public understanding of elections and support a healthier democratic ecosystem in the algorithmic age.

Related Reading: Prediction Markets: A Decade in the Making, Who Will Be Next?

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。