This article analyzes the differences between Jupiter's merger and market expansion strategies and those of Hyperliquid.

Written by: Saurabh Deshpande, Decentralised.co

Translated by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

In November 2023, Blackstone Group acquired a pet care app called Rover. Initially, Rover was just a platform for finding dog walkers or cat sitters. The pet care industry typically consists of tens of thousands of small, mostly localized, and offline service providers. Rover integrated these suppliers into a searchable marketplace, adding review and payment features, making it the default platform for pet care services. By the time Blackstone privatized it in 2024, Rover had become a hub for demand in the field. Pet owners thought of Rover first, and service providers had no choice but to list on this platform.

ZipRecruiter did something similar in the recruitment field. It collected job information from employers, job boards, and applicant tracking systems and distributed it across multiple channels. ZipRecruiter posted job listings on social networks like Facebook. For employers, ZipRecruiter became a one-stop distribution channel; for job seekers, it was a unified entry point to the market. ZipRecruiter does not own companies or positions but owns the relationships with both parties. Once this relationship is established, it can charge for visibility and job matching, which is an introductory lesson in aggregation economics.

Aswath Damodaran refers to this model as "controlling the shelf": consolidating chaotic, decentralized supply, controlling how it is displayed, and charging for access. Ben Thompson calls it "aggregation theory": establishing direct relationships with end users, allowing suppliers to compete to serve them, and extracting value from each transaction. The core characteristics across different fields are consistent: Google with web pages, Airbnb with listings, Amazon with products.

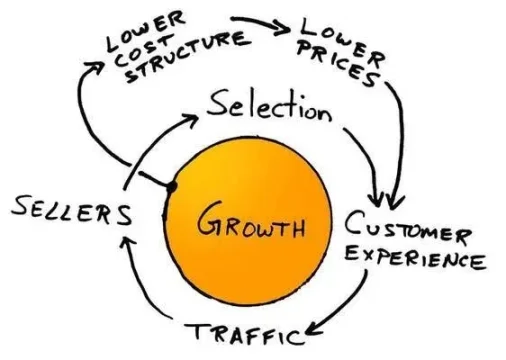

The Amazon flywheel is a classic interpretation of this concept. During the downturn after the internet bubble burst, Jeff Bezos and his team drew on Jim Collins' "flywheel" concept to outline a cycle that every MBA can now recite: more choices lead to better customer experiences, attracting more traffic, which in turn attracts more sellers, reducing unit cost structures, thus providing lower prices, ultimately leading to more choices. The effect of turning the flywheel once is limited, but after turning it a thousand times, the machine begins to roar. Bezos's motto during this period was: "Your profit is my opportunity." The core of this is self-reinforcement: more users, more suppliers, lower costs, ultimately achieving higher profits.

Once this model works, it is nearly perfect. The growth rate of costs is far lower than that of revenue, and products will optimize as users increase. However, it only holds under two conditions: the aggregated content must have value, and the suppliers must find it difficult to exit easily; both are essential, or the moat will become shallow. Take eBay as an example; it aggregated millions of unique niche sellers and buyers in the early 21st century. This aggregation was once highly valuable, but when sellers realized they could build their own stores on Shopify or switch to Amazon, they began to leave. The flywheel does not stop overnight, but if suppliers are no longer controlled, it starts to wobble and eventually becomes ordinary.

Damodaran explains the power of platforms and aggregators in a tangible way. He mentions "controlling the shelf," not in the literal sense of supermarket shelves, but as the space that customers first encounter when demand arises. Controlling this space means deciding what content to display, how to display it, and the cost of entry. You do not need to own the products themselves; you just need to own the relationship with the buyers, and others must go through you to reach the buyers. In analyzing Instacart, Uber, Airbnb, or Zomato, Damodaran repeatedly emphasizes: the aggregator's task is to consolidate the chaotic, decentralized market into a single window and make that window the only one worth paying attention to. Once this is achieved, you can charge for "viewing rights."

Ben Thompson believes that aggregators are businesses that establish direct relationships with end users at internet scale, provide standardized and reliable experiences, and allow suppliers to compete to serve them. At internet scale, you are not the largest store in town but a store that covers all towns simultaneously.

The marginal cost of serving the next customer is almost zero, but the marginal value of owning them is immense. Each customer reinforces your brand, data, and network effects. Because aggregators control demand, suppliers become interchangeable. This does not mean quality is indistinguishable, but rather that when suppliers leave, they cannot take the customer relationships with them. Hotels on Expedia, drivers on Uber, sellers on Amazon—all of them need each other more than the aggregator needs them.

Damodaran's research reminds us that the flywheel does not operate the same way in all markets. For example, Uber aggregates local driver liquidity, but drivers can simultaneously open three apps and choose the first order they receive. This creates vulnerabilities in the moat. On the other hand, Airbnb hosts offer unique listings with limited alternative channels, making their commission more sustainable.

In low-margin fields, shelves may have value, but the commission space is limited, and suppliers can easily push back. This is why Instacart must venture into advertising and white-label logistics to achieve growth.

The economic structure of supply is as important as the number of users on the platform. If the platform has readily available products, you are merely a convenience store with better visibility; but if the content is scarce, differentiated, and hard to replace, people will continue to visit, even if you charge higher fees. Think of the high-end listings on Airbnb.

Why Aggregators Fail

When conditions are lacking, aggregators are no longer flywheels but merely costly carousels.

Quibi is a typical case of failing to control the shelf. The platform had expensive Hollywood content and a polished app but lacked direct channels to users. Potential users had already gathered on YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. These platforms controlled attention, while Quibi locked its content in a standalone app, away from users, leading it to attract users only through ads and promotions.

Excellent aggregators start with zero marginal cost user reach, such as built-in distribution, installation volume, or daily habits. Quibi had none of these and ultimately exhausted its time and funds before building them.

Facebook's Instant Articles faced a similar issue. Its concept was to aggregate content from publishers, accelerate loading within Facebook, and monetize traffic. However, publishers could easily distribute content to their open networks, apps, or other social platforms. Instant Articles never became the default reading platform; it was just one option in the information stream.

Both examples violate the same rule: the business failed to own user relationships in a way that creates default behavior, and suppliers would not be significantly harmed if they exited.

The checklist for excellent aggregators is simple:

Directly connect and own user relationships;

Suppliers must be either unique or interchangeable to avoid being held hostage by a single supplier;

Increase the marginal cost of supply to be close to zero or sufficiently low, allowing the business model to optimize with scale.

If these conditions are not met, you are just another easily replaceable intermediary.

How Liquidity Becomes a Moat

In the crypto industry, projects can build moats in different ways. Some establish trust through licenses and regulations (like USDC), some rely on technology (like Starkware's proof systems or Solana's parallel execution), and others depend on community and network effects (like Farcaster's user graph). However, the hardest to shake is liquidity.

"Executing correctly" is crucial. But if the incentives are strong enough, liquidity can shift rapidly. In 2020, Sushiswap withdrew over $1 billion from Uniswap within days through liquidity mining rewards. The lesson is simple: liquidity stabilizes only when leaving is more painful than staying.

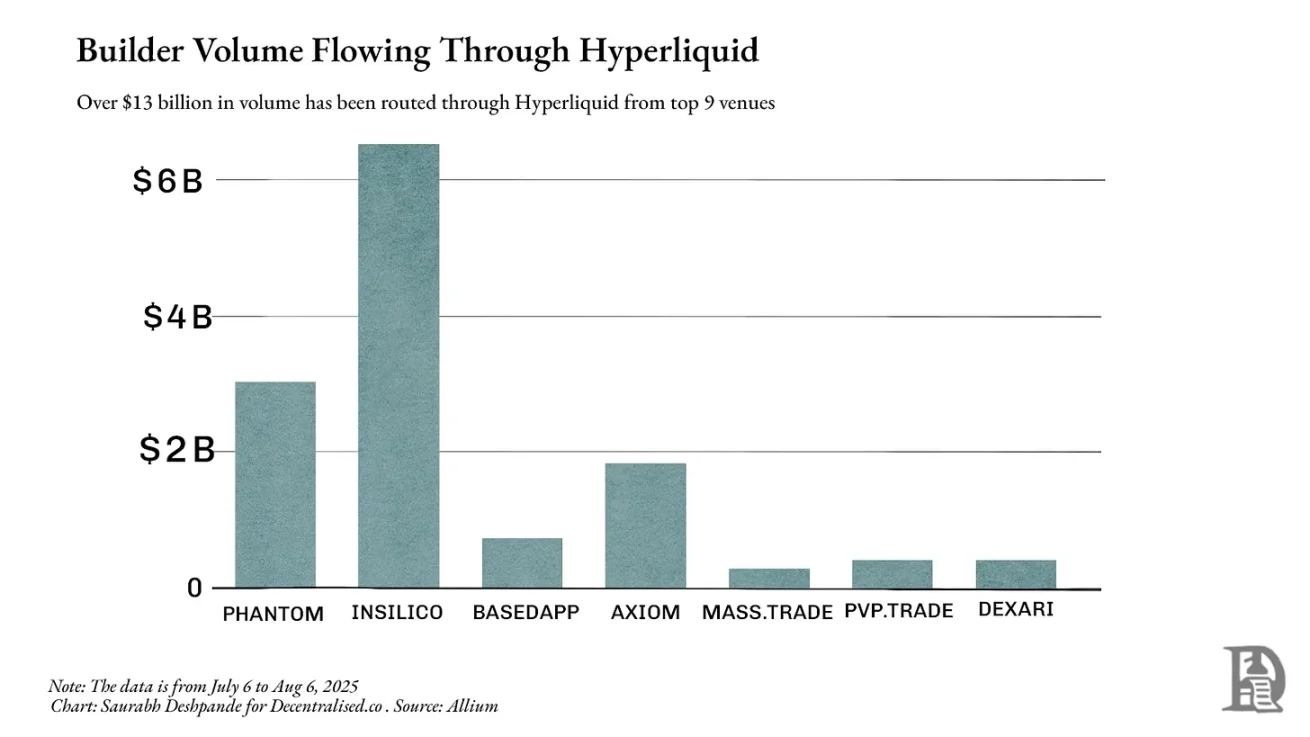

Hyperliquid understands this well. It not only built the deepest order book for perpetual contract exchanges but also allows other applications and wallets to directly access its liquidity. For example, Phantom can tap into Hyperliquid's order flow, providing users with narrow spreads without having to build their own market. In this model, the aggregator needs suppliers more. When traders and applications default to routing through you, you are no longer an ordinary aggregator but a core channel they cannot avoid.

Beyond its own platform, Hyperliquid processed over $13 billion in transaction volume through other builders last month. Phantom processed $3 billion in transaction volume through its routing, earning over $1.5 million. This demonstrates Hyperliquid's current strong network effects.

Liquidity allows you to convert assets without affecting prices. In finance and DeFi, deep liquidity makes trading cheaper, borrowing safer, and derivatives possible. Without liquidity, even the most perfect protocol can become a ghost town. Once successfully established, liquidity often persists. Traders and applications will flow to deep pools, further increasing liquidity, narrowing spreads, and attracting more trades.

This is why protocols like Aave remain robust. Aave has large-scale lending pools of various assets, making it the preferred choice for borrowers and lenders seeking scale and safety. As of August 6, Aave's total locked value across chains exceeded $24 billion. In the past 12 months, borrowers paid $640 million in fees, with platform revenue around $110 million.

Similarly, the Solana-based aggregator Jupiter has evolved from a routing tool to the default entry point for trading on that network. On Ethereum, Uniswap has concentrated most of the spot liquidity, so aggregators like 1inch can only offer marginal improvements. However, on Solana, liquidity is dispersed across platforms like Orca, Raydium, and Serum. Jupiter integrates them into a single routing layer, always providing the best price. Its trading volume once accounted for nearly half of Solana's total computational usage, and any delays or interruptions would immediately affect the execution quality across the network.

By viewing liquidity as an aggregated object, Jupiter's product decisions become easier to understand. Acquisitions, mobile applications, and expansions into new trading and lending products are all aimed at capturing more order flow, keeping liquidity flowing through the Jupiter route, and solidifying its position.

Jupiter is worth paying attention to as it is a clear case of a tool evolving into a liquidity platform within DeFi. Starting with the search for the best spot prices, it gradually became the default routing for Solana liquidity and then expanded to attract entirely new liquidity products. Observing how it navigates through these stages and reinforces each other provides a vivid case for the dynamics of aggregation.

Levels of Aggregation

Three questions serve as a quick checklist for identifying potential aggregators:

What are the key differentiators of existing businesses? Can they be digitized? In DeFi, the differentiator is liquidity. Deep pools can offer narrower spreads and safer loans. Liquidity is already digitized, making it easy to read and compare.

If the differentiator is digitized, does competition shift to user experience? When liquidity can be accessed arbitrarily, competition revolves around execution quality: faster settlements, better routing, fewer failed transactions. Products like BasedApp and Lootbase emerged from this. The former encapsulates DeFi primitives into a smooth mobile experience, while the latter brings Hyperliquid's deep perpetual liquidity to mobile.

If user experience is won, can a virtuous cycle be built? Traders come for better prices, attracting more liquidity, which in turn offers better prices. When liquidity becomes embedded in habits and integrations, it becomes sticky.

Becoming the default entry point in the market means that if suppliers cannot afford your absence, you can charge display fees or dictate order flow in DeFi.

Note: The boundaries between different levels are often blurred. The classification is not precise but provides a mental model for the levels of aggregation.

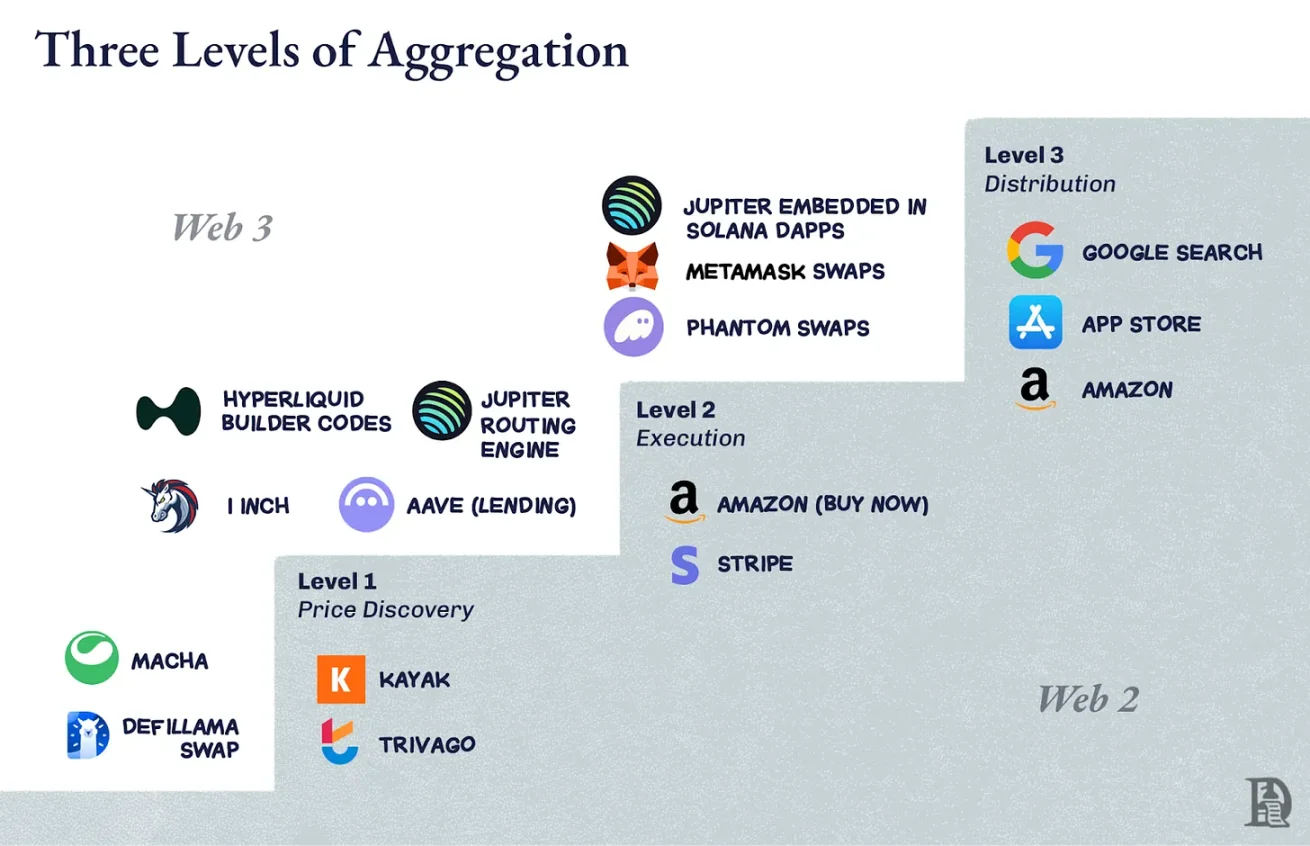

Level One: Price Discovery

This is the most basic function: telling people where the best trades are. Kayak is for flights, Trivago is for hotels. In the crypto space, early DEX aggregators like 1inch or Matcha fall into this category. They check available pools, display the best rates, and provide jump-off points. Price discovery is useful but fragile, as seen with DeFiLlama's exchange function.

If the underlying market is already concentrated (like Ethereum spot trading on Uniswap), the routing improvements are minimal, and users can go directly to the trading venue, making your assistance non-essential.

Level Two: Execution

At this point, you are no longer directing users elsewhere but operating on their behalf. Amazon's "one-click purchase" falls into this level. In DeFi, Aave's lending function is at this level. When borrowing, liquidity is already present in its contracts. Execution increases stickiness because the outcomes are directly related to you: fast settlements and a good experience with no failed transactions.

Level Three: Distribution Control

You become the entry point. Google search for web pages, app stores for mobile applications, all fall into this category. In the crypto space, the built-in exchange tab in wallets can become the starting and ending point for ordinary users.

On Solana, Jupiter has reached this level. It started as a price discovery tool, moved into execution through smart order routing, and then embedded itself into front-ends like Phantom and Drift. A significant amount of Solana transactions are actually Jupiter transactions, even if users never enter "jup.ag." This is distribution control, where suppliers cannot bypass you to reach users.

Climbing the Levels in DeFi

The challenge in DeFi is that liquidity can shift rapidly. Incentives can drain liquidity pools overnight. Therefore, moving from the first level to the third level is not just about becoming a leading aggregator; it also requires creating sufficient reasons for liquidity and order flow to continue routing through you.

On Ethereum, 1inch primarily remains at the second level because Uniswap has completed the aggregation work through concentrated liquidity. Routing still holds value for edge cases, but improvements are limited, and many traders choose to skip it. Additionally, aggregators like CowSwap and KyberSwap also hold significant market shares. Aave belongs to the second level, as it controls execution in a niche area, but it is infrastructure, not a starting point.

Jupiter's advantage on Solana lies in its ability to sequentially climb the three levels. Liquidity is dispersed, making the first level valuable; the routing engine is superior to manual exchanges, naturally transitioning to the second level; by directly integrating wallets and dApps, it reaches the third level, fully controlling the distribution of Solana liquidity. At one point, nearly half of Solana's computational usage came from Jupiter transactions, as both the demand side from traders and the supply side from liquidity pools relied on Jupiter.

Once at the third level, the question becomes, "What else can be run through this distribution?" Amazon started with books and ended up with everything; Google began with search and eventually controlled maps, email, and cloud computing. For Jupiter, distribution is order flow. The obvious next step is to add products like perpetual contracts, lending, and portfolio tracking, leveraging the same liquidity relationships.

A larger move is Jupnet. Solana has yet to match the throughput and execution characteristics of venues like Hyperliquid, which are designed for financial-grade latency and determinism. These characteristics are crucial for scaling the entire financial stack to real-world sizes. A simpler option would be to launch products on chains that already possess these characteristics, but Jupiter has chosen the more challenging path of building Jupnet as an application-controlled low-latency execution layer that runs in parallel with Solana.

Jupnet aims to become shared infrastructure within the Solana ecosystem, supporting perpetual contracts, quote request systems, batch auctions, and other latency-sensitive trades, ultimately settling natively on Solana. If successful, it will provide the speed and certainty expected from vertically integrated venues while retaining users and assets. This is an attempt to bridge the gap between general blockchain throughput and the global financial micro-latency demands without splitting liquidity across chains.

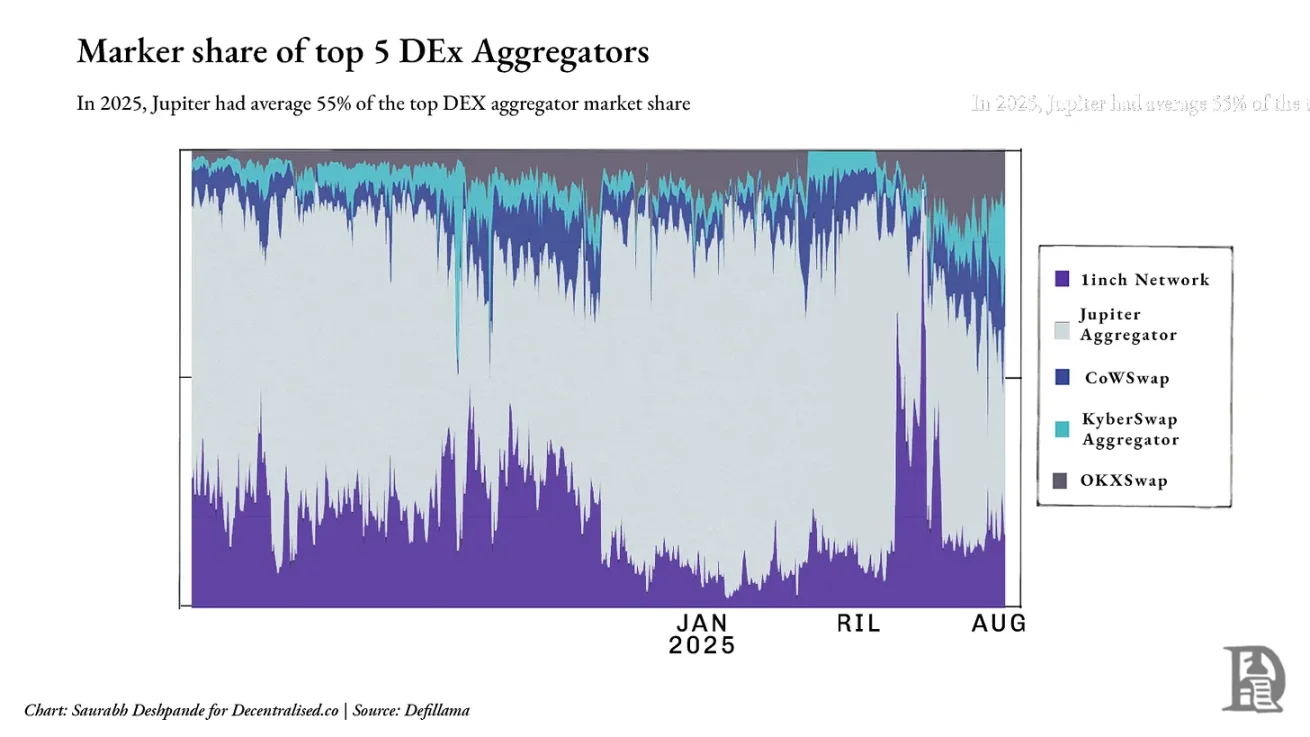

However, it is important to note that while Jupiter dominates within Solana, it still faces fierce competition at the industry level. In the cross-chain space, 1inch, CoWSwap, and OKX Swap maintain significant positions. By 2025, Jupiter is expected to average about 55% of the top five DEX aggregators, but this share fluctuates with on-chain activity and integrations. The following chart shows the degree of decentralization of aggregation layers outside Solana.

Clearly, Jupiter has become the aggregator within the Solana ecosystem. The flywheel has started: more traders bring more liquidity, more liquidity optimizes execution, and better execution attracts more traders. At this point, you are not just a liquidity aggregator but also the shelf, habit, and market entry point. So, when liquidity is no longer sufficient, how do you continue to grow? Jupiter's answer is to acquire projects that have already captured new user flows.

Mergers and Acquisitions as a Growth Engine

Previously, I wrote about two major themes in scaling businesses: the essence of compound innovation and how companies can accelerate this process through mergers and acquisitions. The former concerns building new products, features, or capabilities based on existing advantages, while the latter involves identifying when "buying" is faster than "building" to establish an advantage.

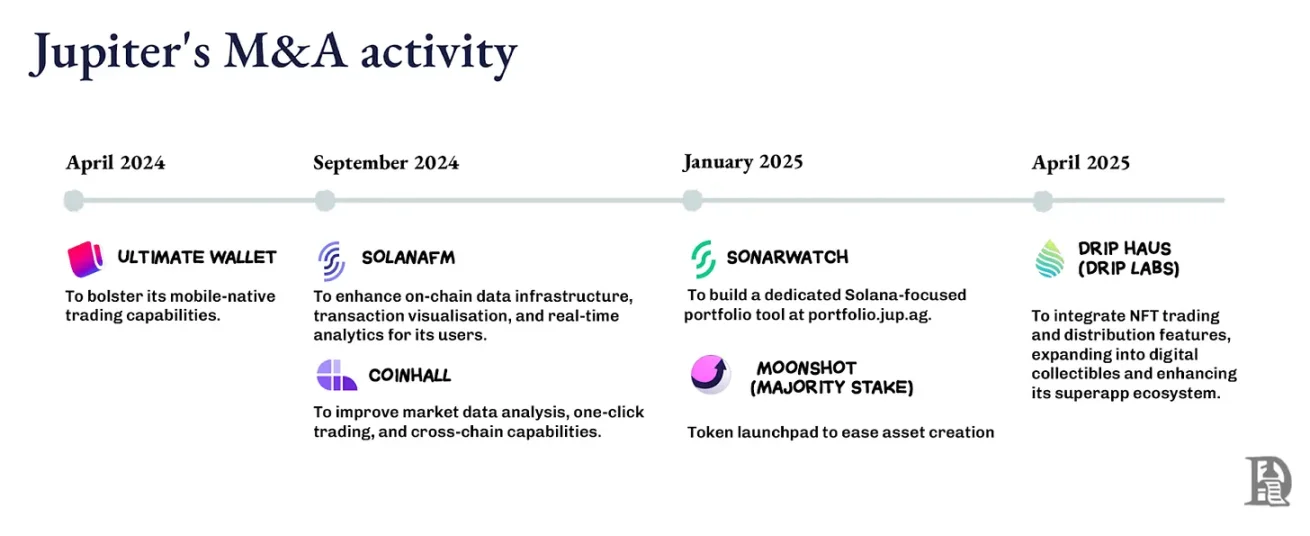

Jupiter's evolution embodies both. Its acquisition strategy is rooted in finding founder teams with real appeal and integrating them into a distribution network that amplifies their impact. The company seeks expert teams in vertical fields to expand coverage without burdening the core roadmap.

This is not just about purchasing functional additions but acquiring teams that have already dominated the market segments targeted by Jupiter. When these teams integrate into Jupiter's distribution wallet interface, API, and routing, their product growth accelerates, and the generated traffic feeds back into Jupiter's core.

Moonshot brings a token launchpad, converting new token creation into direct exchange and trading activities within the Jupiter ecosystem; DRiP adds a community-driven NFT minting and distribution platform, attracting audiences away from trading interfaces and converting them into on-chain behavior; the Portfolio acquisition provides position management tools for active traders. Jupiter could have built these features internally at a lower cost, but its goal is to acquire founders, not just functionality.

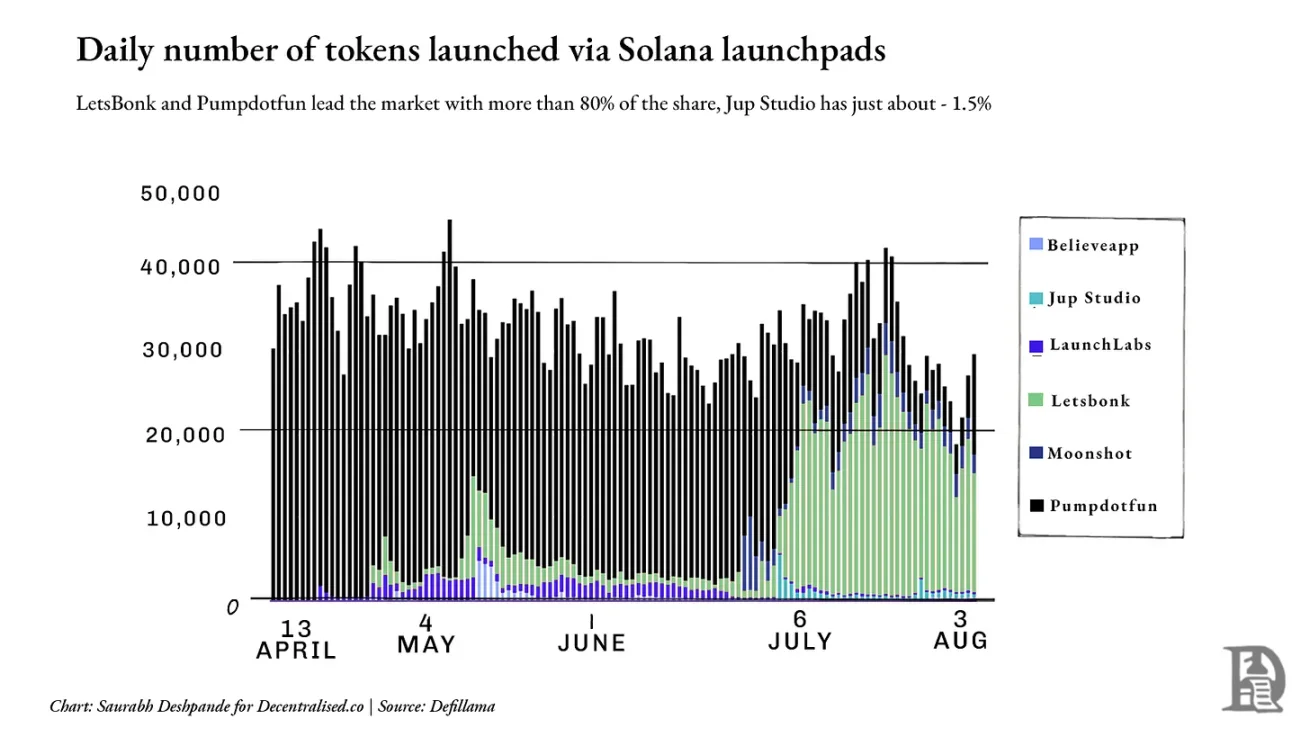

However, some metrics of growth have yet to materialize. For example, in the launchpad space, market leaders Pumpdotfun and LetsBonk control over 80% of daily token issuance, while Jup Studio and Moonshot together account for less than 10%. The following chart shows the dominance of incumbents. In this case, the default landscape may have solidified, and Jupiter may need a radically different approach to break through.

Multiplier Effect: Founder-Led Acquisitions

To broaden the shelf, it is necessary to bring in operators who have already mastered the target market segments. Jupiter's selection criteria are: does the team bring new liquidity or users that strengthen the flywheel? This logic echoes Amazon's early flywheel: each new category or supplier expands "choice," optimizes customer experience, drives more traffic, and attracts more suppliers.

For Jupiter, each acquisition is like adding a new shelf to the store, broadening choices and deepening relationships with traders and liquidity providers.

Acquiring creative founders allows Jupiter to penetrate unfamiliar areas (such as DRiP's NFT culture or mainstream retail token issuance) without diluting its core competencies. These founders understand their niche, have communities that trust them, and can act quickly. Integrating into Jupiter's distribution channels amplifies their reach overnight, while Jupiter gains new user flows and liquidity.

Acquisition cases illustrate this point: Moonshot is a minting and trading platform aimed at mainstream behavior, with tokens issued that can seamlessly transition into exchanges, money markets, and perpetual contracts within the Jupiter ecosystem; DRiP is a creator-first collectibles distribution channel that attracts communities that would not typically engage with trading interfaces.

Moonshot added over 250,000 users within three days of launching the TRUMP token, processing over $1.5 billion in transaction volume; DRiP attracted over 2 million collectors, minting over 200 million collectibles and achieving over 6 million secondary sales.

Integration follows a clear pattern: founders retain control over product direction; products are integrated into the Jupiter interface and backend upon launch, instantly benefiting from its user base, while Jupiter gains new traffic; each acquisition adds unique liquidity primitives (such as issuance, culture, leverage) rather than duplicating existing functions. The core competencies remain unchanged, and all paths still lead back to Jupiter.

In DeFi, code can fork overnight, but market share is hard to replicate. Founder-led acquisitions allow Jupiter to gain market share without losing its core path, making its flywheel harder to replicate. As application-controlled execution and low-latency infrastructure mature, Jupiter may target teams focused on risk engines, matching layers, and specialized venues, integrating them into Jupnet.

Aggregators vs. Suppliers

Overall, two dominant models are emerging in DeFi: Jupiter and Hyperliquid. Both are powerful, but their strategies are entirely different.

Hyperliquid aims to control liquidity rather than directly own end-user relationships. It offers liquidity as a service. If it can build a better user experience, users are welcome to utilize Hyperliquid's order book and execution engine. Builder Codes is based on this concept, allowing others to own the front-end experience while Hyperliquid quietly supports the back-end, which is a supplier-first model.

Jupiter, on the other hand, focuses on distribution. It aims to own the interface, shelf, and market entry, aggregating dispersed liquidity by becoming the default interface and directing it where needed. This means controlling user relationships, not just execution tracks. From perpetual contracts to portfolios, Jupiter attempts to make all financial interfaces start and end within its track.

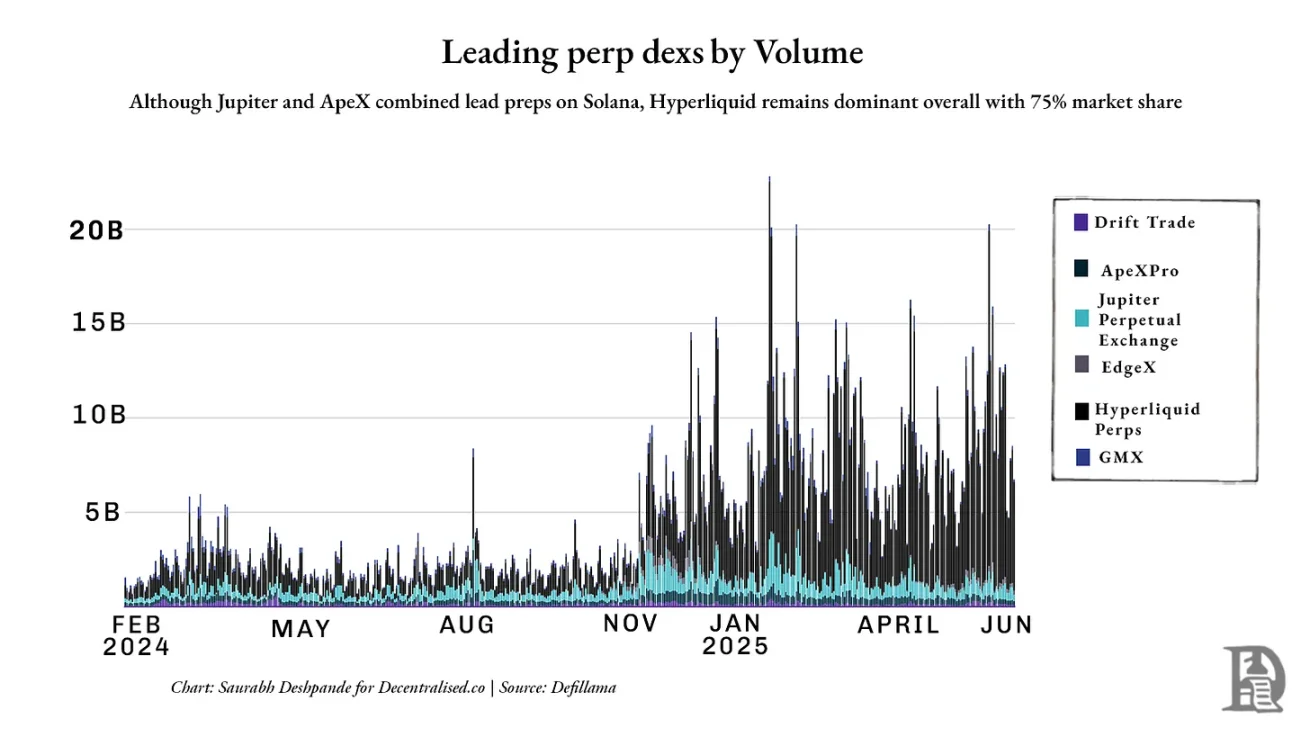

However, perpetual contracts may expose the current limitations of this strategy. Jupiter has made progress on Solana, but Hyperliquid still dominates the market with about 75% of the perpetual DEX market share. The following chart shows Hyperliquid's lead in original trading volume:

Both models bet on scale, but their starting points are opposite. Jupiter believes liquidity follows user interfaces; Hyperliquid believes liquidity is the interface. Jupiter builds entry points, while Hyperliquid builds endpoints.

In practice, we witness differentiation: if broad interfaces and user aggregation are needed, choose Jupiter; if depth, certainty, and composability are required, choose Hyperliquid. One turns liquidity into a dependency network, while the other becomes the underlying structure built by the community.

Winners are not just the first to arrive but those that others cannot abandon.

This is precisely what makes DeFi exciting right now. We are witnessing a philosophical showdown: one side believes distribution is the moat, while the other firmly believes liquidity is.

Applications as New Platforms

When Ethereum Layer 2 first emerged, there was hope it would become a new platform: a neutral ground where applications could be composable, competitive, and scalable. However, it turns out that L2 has not become the platform as imagined, but rather remains at the infrastructure level: providing the technical foundation for speed, security, and scalability without controlling user relationships.

A platform is the interface at the starting point of the user journey, where demand aggregates, habits form, and distribution survives. Few L2s have crossed this line; most are pipelines rather than shelves, rarely building meaningful distribution, and even less often becoming the default entry point for users.

In contrast, applications like Jupiter and Hyperliquid are gradually exhibiting platform characteristics. They have user relationships, embed into daily habits, and strengthen their positions through acquisitions or integrations with other applications. In fact, they are starting to resemble Web2.

Google transcended being a search engine by acquiring YouTube, transforming its search advantage into video dominance; Facebook expanded its control over attention by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp. They targeted adjacent fields where users had already congregated but where they were absent, and crucially, they acquired the core players in those fields. Once acquired, these applications could immediately tap into Google and Facebook's existing distribution flywheel, resulting in the capture of multi-channel user attention.

Jupiter is running a similar strategy. Launchpads, NFT minting tools, portfolio managers, and now Jupnet all serve the same purpose: to expand coverage, capture more user behavior, and route more liquidity to itself. Its strategy is to become the shelf, the default choice, and the starting point for financial interactions.

However, aggregation is not a guaranteed winning strategy. History is full of failed platform acquisitions and aggregation attempts, either due to a lack of user relationships or a misunderstanding of how habits form.

Take Microsoft's acquisition of Nokia as an example. This was a bet on controlling mobile distribution, but users had already shifted to the iOS and Android ecosystems. Microsoft had hardware and software, but its mobile devices and operating systems were either too similar to existing products or insufficient to prompt users to switch. It did not control the application layer, did not win developer loyalty, and did not provide reasons to change behavior. Lacking control over supply or clear differentiation, the shelf went unnoticed.

These cases reflect a core truth: acquisitions alone do not create a flywheel. Without a starting point, habit, or interface, no matter how many features are bundled, users will not follow.

This makes the current moment in DeFi particularly interesting. Jupiter is acquiring front-end, distribution channels, and liquidity primitives, attempting to become the default entry point for the Solana financial stack; Hyperliquid, conversely, is building depth rather than breadth, allowing others to build around its composition.

In a sense, we are witnessing a true platform war unfolding between applications, rather than between public chains as many had anticipated. This raises a larger question: if L2 does not control distribution, when applications on it do, where will the value flow? How will fat protocols fare?

We conclude with an unresolved question, as there is no definitive answer yet. In the future, we will bring sharper insights, new data points, and more stories and analogies to clarify the direction of all this.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。