Who will be the next hundred billion dollar company?

Author: Eric Flaningam

Translation: Deep Tide TechFlow

This is an article analyzing the returns, value growth, lessons learned, and future implications of technology companies over the past 30 years.

The next company to reach a market value of one hundred billion dollars will be different from the last.

This may sound like an obvious statement, but we can't help but fall into the trap of pattern matching. We look for the next Google/Meta/Amazon, or the Uber of industry X, the Airbnb of industry Y, or an AI agent in almost any industry.

Well, to avoid being swept away by the latest trends every week, we must look back at the past. Churchill once said, "The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see."

So I want to analyze the largest companies established in modern history. We should not be constrained by narratives but focus on what the data tells us, using Mauboussin's words to view the problem from an external perspective!

Causal thinking is an innate narrative style. It can convincingly predict the future and explain the past. Our brains are good at creating simple narratives to explain what is happening in the world around us.

The second approach is to adopt statistical thinking, often referred to as an external perspective. Unlike the narrative weaving based on causal relationships, the statistical method looks at reference categories of past similar cases and analyzes their outcomes. The results of these reference categories are known as baseline probabilities.

Therefore, we will delve into:

Data on technology value growth over the past 30 years

Lessons learned from value growth

What these lessons imply for today's technology investments

TL;DR

The next hundred billion dollar company will be fundamentally different from the past

Clarify your playing field: is it a home run, a grand slam, or aiming for outer space like "Space Jam"?

Software is like chicken; 80% of the taste is the same

"Market size" may be the biggest reason why excellent investors miss out on great companies

Companies are often closely related to the technological waves they rely on

Lastly, never underestimate the power of the power law!

Additionally, we launched the Felicis Startup Recruitment Program last week. Feel free to check out the areas we are looking to invest in.

Regarding methodology: The vast majority of technology value is concentrated in the largest companies, so I selected all companies listed on Pitchbook with an IT value of over $5 billion established since 1995. (Note: This does not include Amazon, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple.) I had Claude assist in categorizing these companies, so I believe the exact data is very accurate in direction but not necessarily in essence.

Let's get started.

Data on Technology Company Returns Over 30 Years

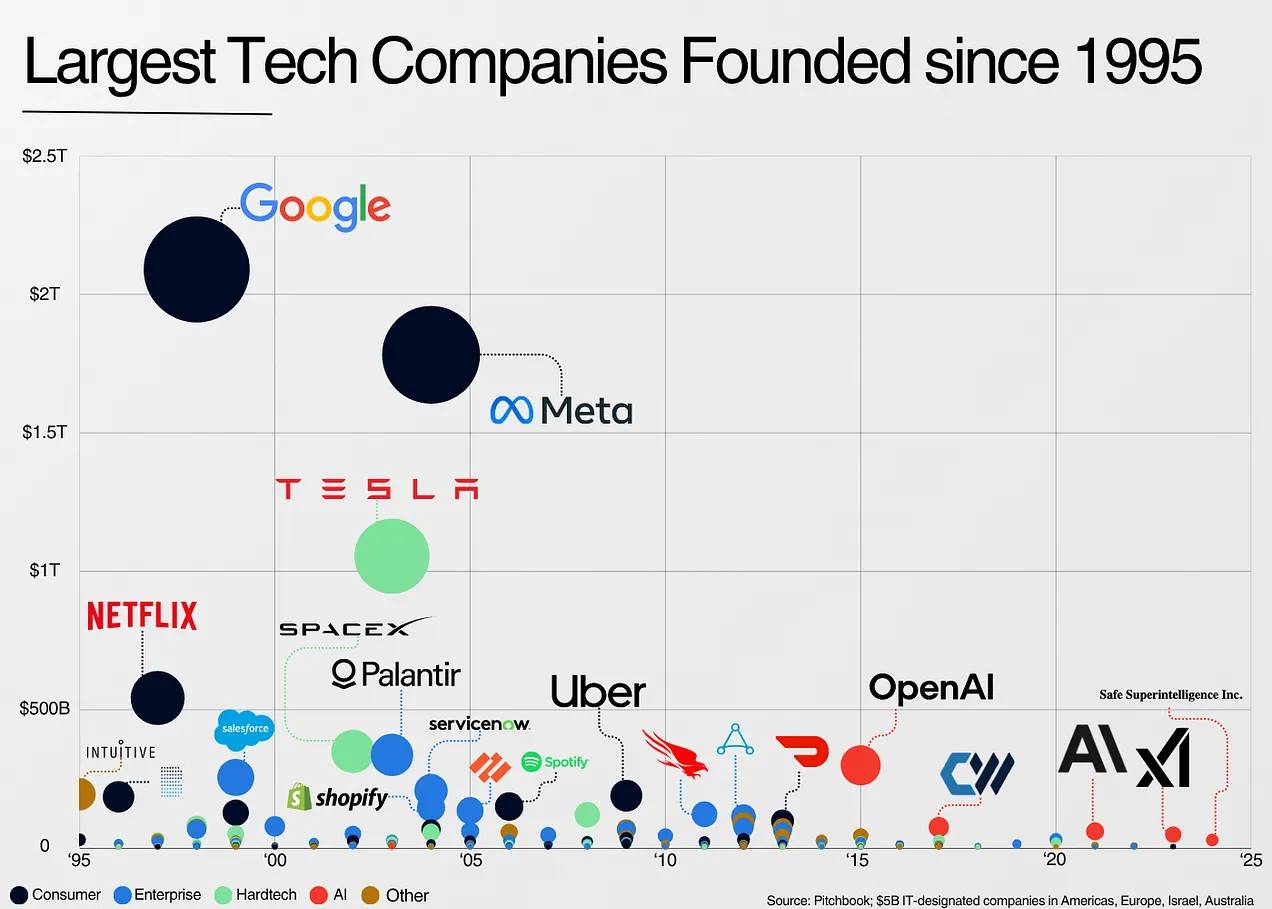

This dataset covers 65 categories and over 300 companies, creating a value of $13 trillion. Here are highlights from some of the most successful companies:

I won't go into detail about the power law, but the top seven companies account for nearly 50% of this dataset.

This leads to the first and most important conclusion:

1. The next hundred billion dollar company will be fundamentally different from the past

First, the value of technology is primarily driven by unique companies, often founded by unique individuals. Because of their "uniqueness," relying on pattern matching makes it easier for us to miss great companies rather than discover them.

If a company has never experienced something like this, it is hard to imagine its future development. How do you estimate Google's market size in 1998? Or Meta's market size in 2004? It's simply impossible.

Take the currently most unique AI company, OpenAI, as an example. It started as a nonprofit research lab with no clear technological vision, the founding team even lost a co-founder, and its governance structure was complex. However, it gradually moved towards becoming one of the most important companies in history. This is the epitome of uniqueness.

The most successful companies have no so-called "public comparables"; they are one of a kind. The largest companies often create entirely new categories, which is why they are difficult to discover.

Neil Mehta defines it as the search for "the very few founders globally who can create most of the value enjoyed by humanity."

To start understanding some data, let's look at the largest companies established since 1995:

Most of these companies either created entirely new industries or reshaped existing ones with significant expansion, almost equivalent to creating their own industry (e.g., Tesla).

Looking at the data by category leads to the following conclusion:

2. Clarify the game you are participating in: is it a home run, a grand slam, or a super challenge aiming for outer space like "Space Jam"?

If we revisit Mauboussin's concept of baseline rates, I believe we need a different mental model to invest in these different categories.

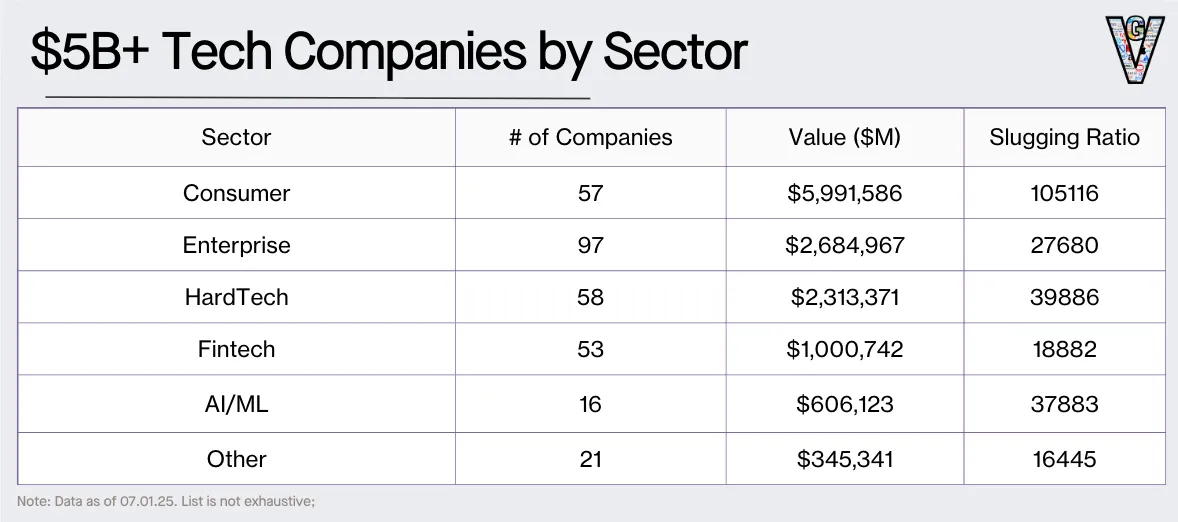

Most of the value is created by consumer goods companies (dominated by the power law). However, the number of enterprise software companies is nearly double that of consumer goods companies.

To illustrate this more intuitively, I added a column for "Average Return" (Slugging Ratio), which is the ratio of "Total Company Value/Number of Companies," to understand the extent of the power law distribution in different industries.

Over the past 30 years, consumer goods companies have often been driven by networked markets, with a true winner-takes-all pattern. If you happen to invest in one of the giants, the only mistake is often underestimating their future scale. Yuri Milner's $10 billion investment in Facebook is a prime example.

If a company can truly integrate network effects into its business model, its advantages will increase immediately.

Hard tech companies (i.e., any company engaged in hardware manufacturing) have the second highest "average return," primarily because hard tech companies face greater survival challenges. Typically, these companies require more capital, take longer to scale, face more challenging product development, are more susceptible to financing difficulties, and find it harder to disrupt existing giants.

However, if they can break through this speed bottleneck, the market opportunity will be enormous.

Yet, the number of consumer goods and hard tech companies is limited. For this reason, enterprise software has become an ideal investment vehicle in the expanding venture capital field.

In non-winner-takes-all markets, rapidly expanding enterprises have strong moats and lower operating costs. In an environment with many venture capital funds, there are more winners to chase, more mature markets, and overall, the risks are much lower. But if everything goes well, there will be significant upside potential. This is a good way to reduce the risks inherent in a high-risk industry.

3. Software is like chicken; 80% of the taste is the same

I borrowed the words of Robert Smith, founder of Vista Equity Partners: "Software companies taste like chicken… they sell different products, but 80% of what they do is almost the same."

If we look at most of the largest enterprise software companies, they are either:

Applications built on databases with unique workflows

The infrastructure that builds these applications

The security that protects these applications

This is not to say that these companies lack differentiation, but rather that their differentiation appears to be much more subtle on the surface. Sales, marketing, and brand awareness are as important, if not more so, than technological differentiation.

In a world where building software is becoming easier, features can be replicated in days, and AI coding tools are becoming increasingly sophisticated, the technological moat in software may be limited to unique data or integration.

The key is that technological differentiation is often not the decisive factor for enterprise software companies.

In this context, I find the argument of "GPT wrappers" interesting, which points out that AI application companies are merely repackaging LLMs. Most enterprise software companies use SQL (or NoSQL) databases and build unique workflows for specific customer groups.

If we look at the largest recent AI enterprise application companies, they are all "large language model wrappers." But this is similar to the largest enterprise software companies of the past decade, which ultimately grew into giants with market values exceeding one hundred billion dollars!

As I mentioned earlier, enterprise software is less risky and more predictable than other categories. However, aside from horizontal enterprise software, market size does not seem to be as important as it appears. "How big can this company get?" and "How big is this market?" are two entirely different questions.

4. "Market size" may be the biggest reason why excellent investors miss out on great companies

If there is one thing that humans find most difficult to cope with, it is uncertainty. And that is precisely what new markets bring.

Palantir, Shopify, Uber, and many other companies have created new markets that previously did not exist, more or less.

Even attempting to add certainty to inherently uncertain questions can lead to foolish behavior.

Taking the famous debate between Aswath Damodaran and Bill Gurley on valuing Uber as an example, Gurley's conclusion is that Uber's potential market size could be 25 times what Damodaran initially estimated.

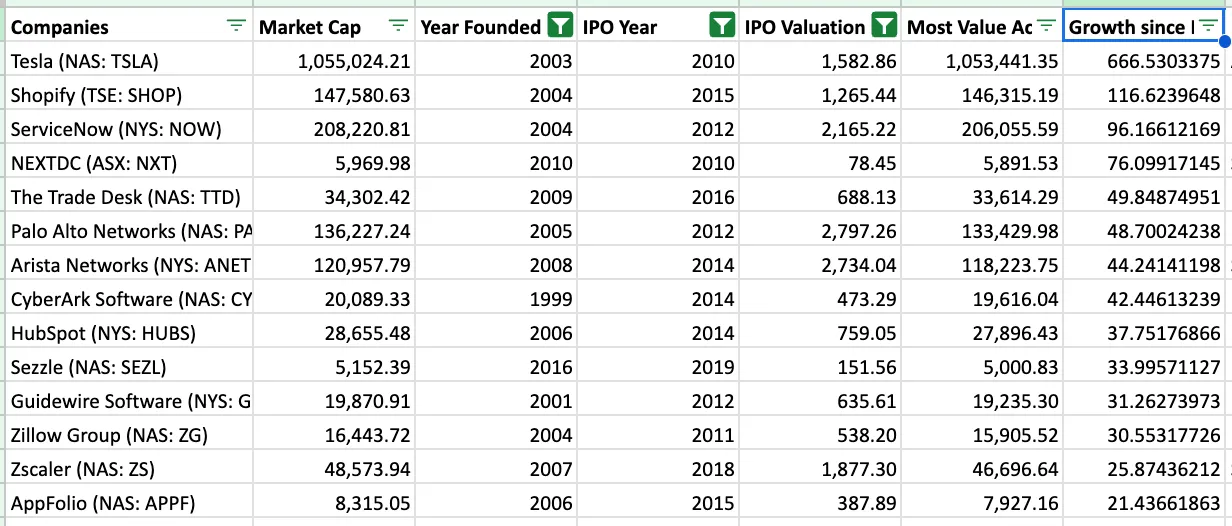

I studied companies founded since 2010 that achieved the highest multiple returns in the public market, which can be seen as an undervaluation indicator.

Some patterns emerged:

Investors underestimated market size, especially for market-expanding companies or vertical markets: Companies like Shopify, Guidewire, Zillow, and AppFolio were undervalued. Similarly, in the private market, investors also underestimated vertical software companies like Toast and ServiceTitan.

As new business models surpass old ones, companies experience tailwinds of multiple expansions: Tesla (the most extreme example) and all listed software companies have reshaped their multiples compared to existing companies they previously competed against. Today, Tesla alone has a market value close to $1 trillion, more than double the combined market value of all major automakers when it entered the market.

Investors underestimated the power of platforms: ServiceNow, Palo Alto, Crowdstrike, Workday, Atlassian, and Datadog have all expanded their markets by broadening their product lines. As software development becomes easier, the technological differences between platforms are diminishing, leading customers to prefer platforms over point solutions. In the era of integration, platformization is a good thing!

This is not to say that market size is unimportant, but rather to emphasize that market size is easily misestimated.

5. Companies are often closely related to the technological waves they rely on

If the previous section was about "market size," this section addresses the "why now?" question. A well-known "why now?" question in venture capital is: Why wasn't this company created before? What new insights allow this company to exist now?

In most cases, the answer is that new technological waves have made the existence of the company possible. Today, that wave is artificial intelligence (AI). In the past, it was the internet, followed by mobile technology, then the convergence of the internet and mobile, and finally cloud computing.

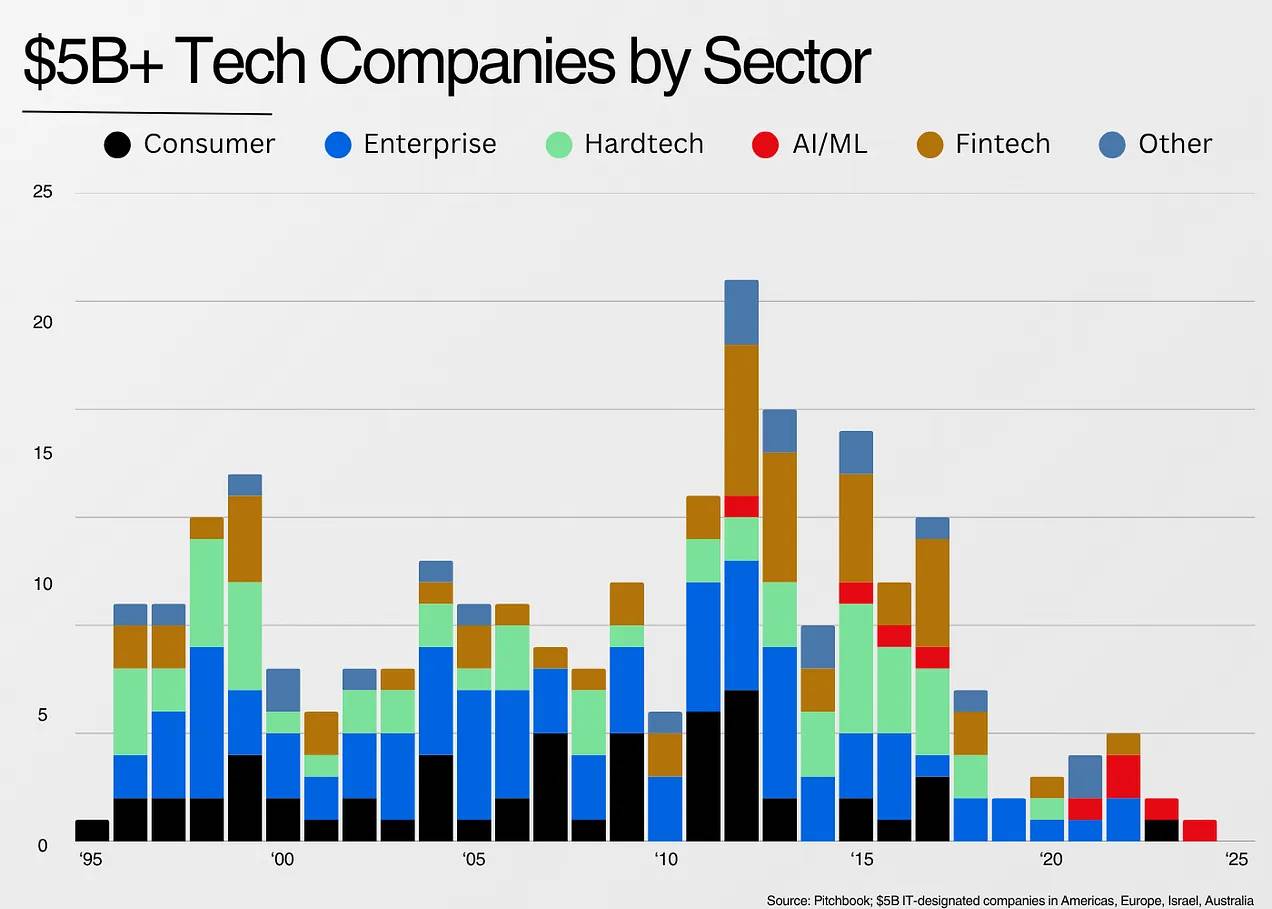

We can see below the timeline of companies worth over $5 billion categorized by industry:

The internet connected the globe, giving rise to the emergence of aggregation business models.

Mobile technology took it a step further, putting the internet in everyone's hands and opening up new consumer markets.

Fintech is a rare example that demonstrates how regulation can drive the development of new technology industries. Especially after the 2010s, with the implementation of the Durbin Amendment, fintech experienced a boom.

Cloud computing is the most disruptive wave in the history of technology, allowing companies to build software through credit card payments rather than relying on data centers.

Now, with the development of artificial intelligence (AI), which companies will be inspired by this? What will they look like?

AI programming tools further advance cloud computing, enabling not just developers but anyone to create software. This will lead to a software explosion similar to that of the cloud computing era.

AI has also unlocked the ability to automate voice and text workflow processing. We are already seeing this trend in programming, customer service, and AI documentation, but it will expand to more application scenarios in the future.

This expands the software market in ways we have never seen before. For example, in this dataset, no legitimate software company's valuation exceeded $5 billion. Yet, Harvey, founded just three years ago, has already reached a valuation of $5 billion.

Rex Woodbury proposed a great thought experiment regarding the current state of AI:

I like Alfred Lin's analogy between mobile and cloud. In the mobile era, a valuable exercise was to break down the functions of the iPhone and then predict which companies each function could empower. He gave an example: GPS allowed delivery drivers to use Google Maps to deliver food. This gave rise to DoorDash.

Technological waves open a narrow window for new companies, and we are now seeing this window emerging.

6. What will happen next?

Last week, while reading "The History" by Will and Ariel Durant, I came across a statement: History mocks all attempts to fit it into theoretical models or logical frameworks; it always breaks our generalizations and overturns all rules. History itself is complex and ever-changing, filled with wonders and anomalies like the Baroque style.

Perhaps this article is foolish, as it even attempts to fit the most anomalous industries into a logical framework!

What remains unchanged is human nature. Analyzing from a reverse perspective, humans often find it difficult to imagine exponential growth, struggle to cope with anomalies, and have trouble dealing with uncertainty.

To handle this uncertainty, our best options are:

Understand the "baseline rates" of company categories (what could happen)

Understand where differentiation comes from (in the software field, sometimes it mainly comes from sales and marketing)

Treat market size as a first-principles exercise in solving problems rather than a simple pattern-matching activity

Recognize that the emergence of each wave of companies is unique and unpredictable, and that is where its value lies.

Steve Jobs once said about computers: "I think one of the things that really distinguishes us from higher primates is that we are tool makers… For me, the computer is the most remarkable tool we have ever invented; it is like a bicycle for our minds."

Jobs was right. Computers have unleashed an unprecedented wave of creativity.

Today, we are witnessing the birth of the greatest "bicycle for the mind" in history. Living in this era is truly exhilarating!

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。