They lost the battle against Facebook but earned more from Facebook than most early employees.

Written by: Thejaswini M A

Translated by: Saoirse, Foresight News

The mediator just announced Facebook's settlement proposal: $65 million. The room fell silent as Mark Zuckerberg's lawyers awaited a response.

For most people, they might have taken the cash and disappeared. Tyler Winklevoss looked at his brother Cameron Winklevoss, then turned to the table across from them.

"We want stock."

The lawyers exchanged glances. At that time, Facebook was still a private company; the stock could plummet, and the company could fail. Cash was tangible, but stock was a gamble.

But Tyler's response would define their lives for the next decade. In a strict sense, they were betting the entire settlement on a company that had stolen their ideas.

When Facebook went public in 2012, their $45 million in stock skyrocketed to nearly $500 million.

The Winklevoss brothers executed one of the boldest moves in Silicon Valley history: they lost the battle against Facebook but earned more from Facebook than most early employees.

In 2013, they struck again. This time, they seized the opportunity with precision.

The Growth Trajectory of the Mirror Twins

Before becoming cryptocurrency billionaires and suing Facebook, Cameron and Tyler were practically mirror images of each other.

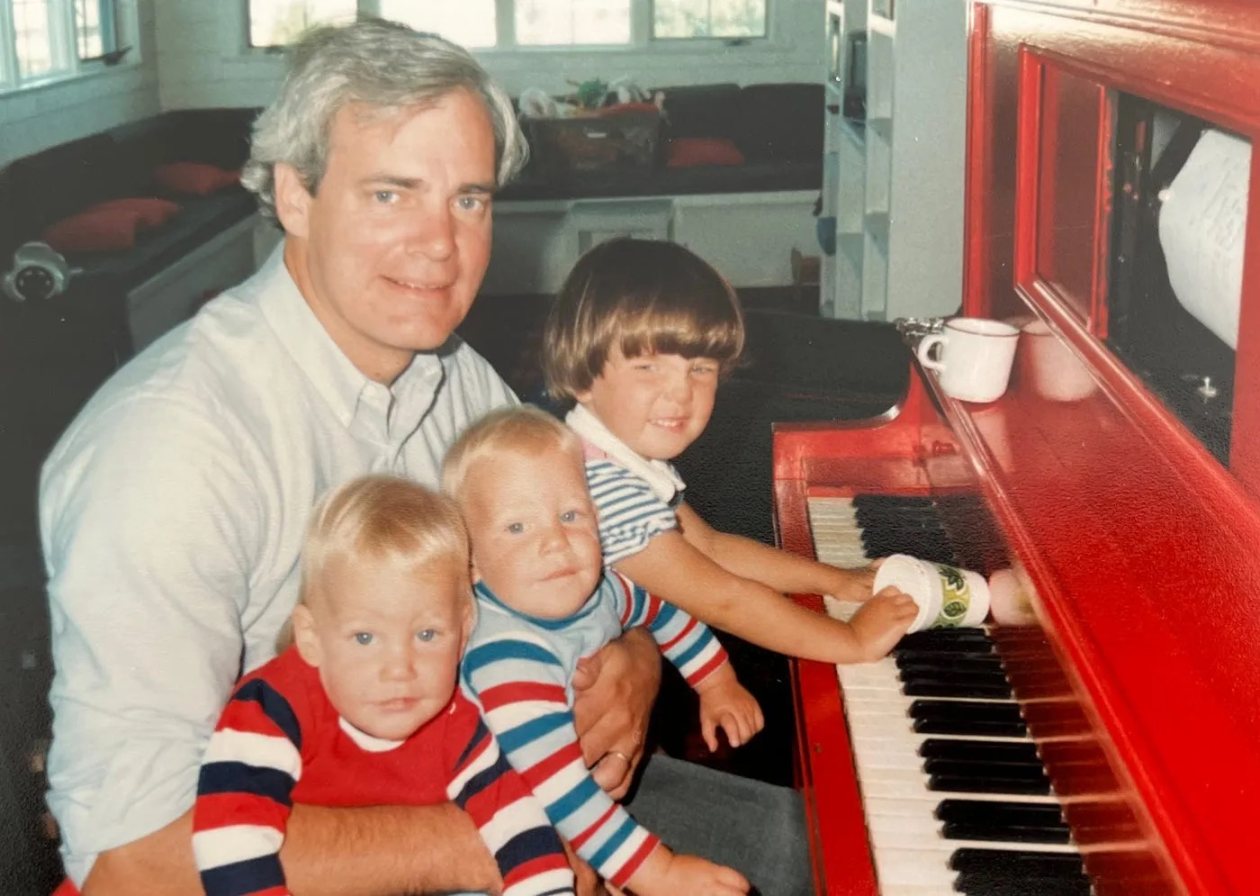

Born on August 21, 1981, in Greenwich, Connecticut, they are identical twins with one key difference: Cameron is left-handed, and Tyler is right-handed, perfectly symmetrical.

They were tall and strong from a young age, and remarkably synchronized. At 13, they taught themselves HTML and built websites for local businesses; as teenagers, they started their first web company, creating websites for any paying clients.

At the Greenwich Country Day School and later at Brunswick School, they were introduced to rowing and co-founded the school's rowing team.

In an eight-man shell, timing is everything. Even a fraction of a second too slow can cost you the race. Achieving perfect synchronization requires understanding teammates, sensing the water flow, and making split-second decisions under pressure.

Their skills progressed rapidly, allowing them to join the Harvard rowing team and even compete in the Olympics.

But what rowing taught them was far more valuable than athletic honors: it was the art of timing and seamless collaboration.

Harvard Lab

In 2000, the Winklevoss brothers entered Harvard, majoring in economics while harboring Olympic dreams.

Cameron joined the men's varsity rowing team, the elite Porcellian Club, and the Harvard Crimson Club. Both brothers devoted themselves to rowing training, a dedication that later took them to the international stage.

In 2004, they joined the Harvard rowing team (nicknamed "The God Squad") and set an undefeated record for the college season, winning the Eastern Sprints, the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championships, and the Harvard-Yale Regatta.

But outside of rowing, a far-reaching idea quietly took root.

In December 2002, during their junior year, the brothers conceived HarvardConnection (later renamed ConnectU) while studying the social dynamics of elite college life.

Their idea was to create a social network exclusively for college students, starting at Harvard and expanding to other elite institutions. They recognized a core need of their generation: students craved online social interaction, but the existing tools were clunky and lacked focus.

The problem was, they were athletes and economics students, not programmers.

They needed help, someone smart who could understand their vision.

Enter Mark Zuckerberg.

In October 2003, at Harvard's Kirkland House dining hall, the brothers introduced Zuckerberg to their social network concept. At the time, the sophomore computer science student was reportedly developing a site called Facemash, where users could rate photos of others.

He was the perfect candidate.

They elaborated on the vision for HarvardConnection, and Zuckerberg listened intently, nodding frequently and asking about functionality and technical specifications, appearing genuinely interested. They scheduled follow-up meetings.

In the following weeks, everything progressed smoothly. Zuckerberg actively participated in discussions, researching implementation plans, and seemed fully invested in the project. The brothers thought they had finally found the right programmer.

On January 11, 2004, just as the brothers were waiting for their next meeting with Zuckerberg, he registered the domain: thefacebook.com.

Four days later, he did not show up for the meeting but launched Facebook instead.

The brothers read about this news in the campus newspaper, The Harvard Crimson, and realized that the programmer they had hired had become their competitor. They understood they had been played.

Legal Battle

In 2004, ConnectU sued Facebook, accusing Zuckerberg of stealing their ideas and breaching a verbal agreement, claiming he built a competing platform using their concept.

What followed was four years of legal wrangling. More and more lawyers got involved, and the case became sensational. But this lawsuit allowed the brothers to witness one of the most significant technological transformations in human history up close.

During the litigation, they watched Facebook expand from college campuses to high schools and then open to everyone. The platform they envisioned was conquering the world, just under a different name.

They studied Facebook's user growth, analyzed its business model, and observed the network effects. By the time they sat at the settlement negotiation table in 2008, their understanding of Facebook was likely greater than that of anyone outside the company.

But at that moment, their fiercest competition was not on the rowing course but in the courtroom.

In 2008, during the settlement, the brothers chose to take Facebook stock instead of cash, a decision that proved to be visionary. When Facebook went public in 2012, their $45 million in stock had appreciated to nearly $500 million.

This demonstrated that even if the Winklevoss brothers lost a battle, they could still win the war.

During the legal disputes, their athletic careers continued. In 2007, at the Pan American Games in Rio de Janeiro, Cameron won a gold medal in the men's eight and a silver in the men's four without coxswain; the following year, the brothers competed together in the Beijing Olympics, finishing sixth in the men's double sculls, establishing themselves among the world's top rowers.

The Bitcoin Revelation

After becoming wealthy from the Facebook settlement, the brothers attempted to become angel investors in Silicon Valley but faced repeated rejections. All startups turned them down. The reason: Mark Zuckerberg would never acquire a company that the Winklevoss brothers invested in; their money had become a "hot potato."

Feeling disheartened, the two escaped to Ibiza. One night, at a club, a stranger named David Azar approached them with a dollar bill and said, "A revolution."

On the beach, David explained Bitcoin to them, a completely decentralized digital currency with a total supply of only 21 million coins. In 2012, hardly anyone had heard of it.

As Harvard economics graduates, they immediately recognized Bitcoin's potential: it was like "digital gold," possessing all the value attributes of gold but even better.

In 2013, when Wall Street was still pondering what cryptocurrency was, the Winklevoss brothers began buying in large quantities.

They invested $11 million when Bitcoin was priced at $100, acquiring about 100,000 bitcoins, which represented 1% of the total Bitcoin supply at the time.

Think about it: these two Olympic athletes and Harvard graduates could have led a stable life but instead bet millions of dollars on a digital token that most people associated with "drug dealers" and "anarchists."

Their friends must have thought they were crazy.

But the brothers witnessed firsthand an idea that originated from a dorm room evolve into a multi-billion-dollar giant. They understood that what seemed "impossible" could quickly become "inevitable."

By 2017, when the price of Bitcoin soared to $20,000, their $11 million investment had grown to over $1 billion, making them among the first publicly known Bitcoin billionaires.

The pattern was clear: Cameron Winklevoss and Tyler Winklevoss could always see opportunities that others could not.

Building Infrastructure

The brothers did not stop at buying Bitcoin and waiting for its value to rise; they began building the infrastructure to promote the adoption of cryptocurrency.

Winklevoss Capital is dedicated to providing seed funding for startups constructing the new digital economy infrastructure, covering exchanges (like BitInstant), blockchain infrastructure, custody tools, analytics platforms, and later including DeFi and NFT projects. Their investment portfolio is extensive, ranging from protocol developers (like Protocol Labs and Filecoin) to cryptocurrency mining energy infrastructure.

In 2013, the brothers submitted the first Bitcoin ETF application to the U.S. SEC. It was a far-fetched idea, almost destined to fail, but someone had to take the first step. In March 2017, the SEC rejected the application, citing "concerns about market manipulation"; they tried again, only to be rejected in July 2018. But the regulatory groundwork they laid paved the way for future applicants. The approval of the spot Bitcoin ETF in January 2024 is a result of the framework they began building ten years ago.

In 2014, BitInstant CEO Charlie Shrem was arrested at the airport for money laundering related to Silk Road transactions, leading to the company's closure; at the same time, the largest Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, was hacked, resulting in the loss of 800,000 bitcoins. The infrastructure they invested in was on shaky ground, and Bitcoin was in jeopardy.

But they saw an opportunity in the chaos: the Bitcoin ecosystem needed legitimate, regulated companies.

In 2014, they founded Gemini, one of the first regulated cryptocurrency exchanges in the United States. While other crypto platforms operated in legal gray areas, Gemini worked directly with New York state regulators to establish a clear compliance framework.

They understood that for cryptocurrency to go mainstream, there needed to be infrastructure that met institutional standards. The New York State Department of Financial Services granted Gemini a "limited purpose trust charter," making it one of the first licensed Bitcoin exchanges in the U.S.

By 2021, Gemini was valued at $7.1 billion, with the brothers holding at least 75% of the shares; today, the exchange manages over $10 billion in assets and supports more than 80 cryptocurrencies.

Through Winklevoss Capital, they invested in 23 cryptocurrency projects, including Protocol Labs and participating in the 2017 Filecoin funding.

They did not fight against regulators but instead worked to educate them; they did not exploit regulatory loopholes but integrated compliance concepts from the product design stage.

In 2024, Gemini reached a $218 million settlement due to the Earn program, but the exchange survived and continued operations.

The brothers understood that having technology alone was not enough; regulatory approval would determine the fate of cryptocurrency.

In 2024, they each donated $1 million in Bitcoin to Donald Trump's presidential campaign, clearly expressing support for politically friendly leadership towards cryptocurrency. Although the donations exceeded federal limits and some were returned, they made their position known.

They openly criticized former SEC Chairman Gary Gensler's "overly aggressive enforcement." The SEC's lawsuit against Gemini was not only a direct challenge to their business model but also made this regulatory battle personal and professional. In June 2025, Gemini secretly submitted its IPO application.

Current Achievements

Forbes currently estimates that each brother is worth $4.4 billion, totaling about $9 billion, with their Bitcoin holdings making up the largest share of their wealth.

Their cryptocurrency assets include approximately 70,000 bitcoins (valued at $4.48 billion) and a significant amount of Ethereum, Filecoin, and other digital assets.

Gemini remains one of the most trusted cryptocurrency exchanges globally, with institutional-grade security and compliance qualifications. Its upcoming IPO is an important step towards integration into mainstream financial markets.

In February 2025, the brothers became partial shareholders of the English football club Real Bedford, investing $4.5 million. The team currently plays at the eighth tier of English football, and they are collaborating with cryptocurrency podcaster Peter McCormack to try to bring this semi-professional team into the Premier League.

Their father, Howard, donated $4 million in Bitcoin to Grove City College in 2024, marking the first time the school received a Bitcoin donation, which will fund the newly named Winklevoss School of Business.

The brothers themselves donated $10 million to Greenwich Country Day School, setting a record for alumni donations at the school.

They have publicly stated that even if Bitcoin's market value reaches that of gold, they will not sell their holdings. This indicates their belief that Bitcoin is not only a means of storing value but also a fundamental reimagining of currency itself.

From the Harvard Crimson exposing Mark Zuckerberg's betrayal to that dollar bill on Ibiza beach that sparked a revolution. These two moments witnessed their transformation from "being blindsided" to "seeing the opportunity." Over the years, some have said the Winklevoss brothers "missed the boat," but the truth is, they were simply standing at the platform for the next train ahead of time.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。