Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Saoirse, Foresight News

Today, the practice of using zero-knowledge proofs to protect privacy in digital identity systems has become somewhat mainstream. Various zero-knowledge proof passport projects (literally translated as ZK-passport projects, referring to digital identity projects based on zero-knowledge proof technology) are developing user-friendly software packages that allow users to prove they hold valid identification without revealing any details about their identity. World ID (formerly known as Worldcoin), which uses biometric technology for verification and ensures privacy through zero-knowledge proofs, has recently surpassed 10 million users. A digital identity government project in Taiwan has also utilized zero-knowledge proofs, and the European Union is increasingly focusing on zero-knowledge proofs in its digital identity work.

On the surface, the widespread adoption of zero-knowledge proof-based digital identities seems to be a significant victory for d/acc (note: a concept proposed by Vitalik in 2023, advocating for the advancement of decentralized technology through technical tools such as encryption and blockchain, while defending against potential risks and balancing technological innovation with security, privacy, and human autonomy). It can protect our social media, voting systems, and various internet services from witch attacks and bot manipulation without sacrificing privacy. But is it really that simple? Do zero-knowledge proof-based identities still carry risks? This article will clarify the following points:

- Zero-knowledge proof wrapping (ZK-wrapping) addresses many important issues.

- Identities wrapped in zero-knowledge proofs still carry risks. These risks seem largely unrelated to biometrics or passports; most risks (privacy breaches, susceptibility to coercion, system errors, etc.) primarily stem from the rigid enforcement of the "one person, one identity" attribute.

- The other extreme, using "proof of wealth" to counter witch attacks, is insufficient in most application scenarios, so we need some form of "quasi-identity" solution.

- The theoretically ideal state lies between the two, where the cost of obtaining N identities is N².

- This ideal state is difficult to achieve in practice, but a suitable "multiple identity" approach comes close, making it the most realistic solution. Multiple identities can be explicit (e.g., identity based on social graphs) or implicit (various types of zero-knowledge proof identities coexisting, with no single type approaching a 100% market share).

How Do Zero-Knowledge Proof Wrapped Identities Work?

Imagine you obtained a World ID by scanning your iris, or you used your phone's NFC reader to scan a passport, gaining an identity based on a zero-knowledge proof passport. For the argument of this article, the core attributes of these two methods are consistent (with only a few marginal differences, such as in cases of multiple nationalities).

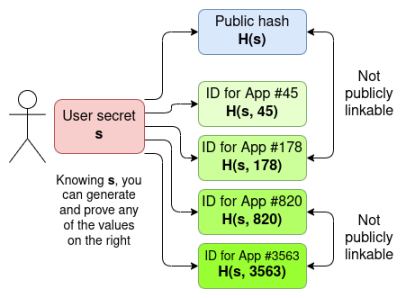

On your phone, there is a secret value s. In the global on-chain registry, there is a public hash value H(s). When logging into an application, you generate a user ID specific to that application, namely H(s, app_name), and verify through zero-knowledge proof that this ID corresponds to a public hash value in the registry derived from the same secret value s. Therefore, each public hash value can generate only one ID for each application, but it will never reveal which public hash value corresponds to a specific application ID.

In reality, the design may be somewhat more complex. In World ID, the application-specific ID is actually a hash that includes the application ID and session ID, allowing different operations within the same application to be unlinkable. The design of zero-knowledge proof passports can also be constructed in a similar manner.

Before discussing the drawbacks of this type of identity, it is essential to recognize the advantages it brings. Outside the niche field of zero-knowledge proof identities (ZKID), to prove oneself to services requiring identity verification, you often have to disclose your complete legal identity. This severely violates the "principle of least privilege" in computer security: a process should only obtain the minimum permissions and information necessary to complete its task. They need to prove you are not a bot, that you are over 18, or that you come from a specific country, but what they receive is a pointer to your complete identity.

The best improvement currently achievable is to use indirect tokens such as phone numbers or credit card numbers: at this point, the entity that knows your phone/credit card number is associated with your in-app activities, and the entity that knows your phone/credit card number is associated with your legal identity (company or bank) are separate. However, this separation is extremely fragile: phone numbers and other types of information can be leaked at any time.

With the help of zero-knowledge proof wrapping technology (ZK-wrapping, a technique that uses zero-knowledge proofs to protect user identity privacy, allowing users to prove their identity without disclosing sensitive information), the aforementioned issues can largely be resolved. However, the next point to discuss is one that is less frequently mentioned: there are still some problems that not only remain unresolved but may even become more severe due to the strict limitation of "one person, one identity" in such solutions.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Cannot Achieve Anonymity

Assuming a zero-knowledge proof identity (ZK-identity) platform operates as expected, strictly reproducing all the logic mentioned above, and has even found a way to protect users' private information long-term without relying on centralized institutions. However, at the same time, we can make a realistic assumption: applications will not actively cooperate with privacy protection; they will adhere to a "pragmatism" principle, and the design solutions they adopt, while claiming to "maximize user convenience," will seem to always lean towards their own political and commercial interests.

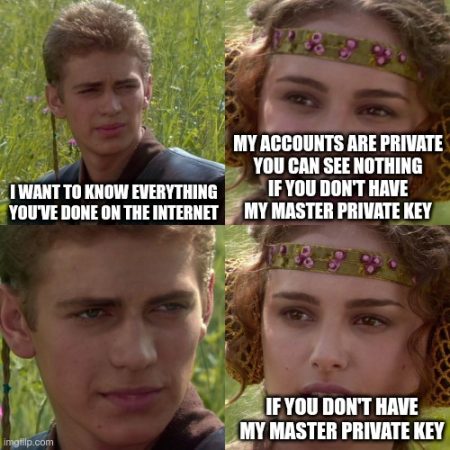

In such a scenario, social media applications will not adopt complex designs like frequently rotating session keys but will assign each user a unique application-specific ID. Due to the identity system adhering to the "one person, one identity" rule, users can only have one account (in contrast to the current "weak ID" systems, such as Google accounts, where an average person can easily register about five). In the real world, achieving anonymity typically requires multiple accounts: one for "regular identity," and others for various anonymous identities (see "finsta and rinsta"). Therefore, under this model, the anonymity that users can actually obtain is likely lower than the current level. As a result, even a zero-knowledge proof-wrapped "one person, one identity" system may gradually lead us to a world where all activities must be tied to a single public identity. In an era of increasing risks (such as drone surveillance), depriving people of the choice to protect themselves through anonymity will have serious negative consequences.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Cannot Protect You from Coercion

Even if you do not disclose your secret value s and no one can see the public associations between your accounts, what if someone forces you to disclose it? Governments may compel individuals to reveal their secret values to view all their activities. This is not mere speculation: the U.S. government has begun requiring visa applicants to disclose their social media accounts. Additionally, employers can easily make the disclosure of complete public information a condition of employment. Some applications may even technically require users to disclose their identities on other applications to register (using app login defaults to perform this action).

In these cases, the value of the zero-knowledge proof attribute disappears, but the drawbacks of the "one account per person" attribute still exist.

We might be able to reduce coercion risks through design optimization: for example, using a multi-party computation mechanism to generate each application-specific ID, allowing users and service providers to participate together. In this way, without the involvement of the application operator, users would be unable to prove their application-specific ID. This would increase the difficulty of coercing others to disclose their complete identity, but it cannot completely eliminate this possibility, and such solutions have other drawbacks, such as requiring application developers to be active entities rather than passive on-chain smart contracts (which do not require continuous intervention).

Zero-Knowledge Proofs Cannot Solve Non-Privacy Risks

All forms of identity have edge cases:

- Government-rooted IDs, including passports, cannot cover stateless individuals or those who have not yet obtained such documents.

- On the other hand, these government-based identity systems grant unique privileges to holders of multiple nationalities.

- Passport issuing agencies may be hacked, and intelligence agencies from hostile nations may even forge millions of false identities (for example, if Russian-style "guerrilla elections" become prevalent, false identities could be used to manipulate elections).

- For individuals whose relevant biometric features are impaired due to injury or illness, biometric identities may become completely ineffective.

- Biometric identities may be deceived by replicas. If the value of biometric identities becomes extremely high, we may even see individuals specializing in cultivating human organs solely to "mass-produce" such identities.

These edge cases pose the greatest danger in systems attempting to maintain the "one person, one identity" attribute, and they are unrelated to privacy. Therefore, zero-knowledge proofs are powerless against them.

Relying on "Proof of Wealth" to Prevent Witch Attacks is Insufficient, So We Need Some Form of Identity System

Within the pure crypto-punk community, a common alternative is to rely entirely on "proof of wealth" to prevent witch attacks, rather than building any form of identity system. By imposing a certain cost for each account, it can prevent individuals from easily creating numerous accounts. This practice has precedents on the internet; for example, the Somethingawful forum requires a one-time fee of $10 to register an account, which is non-refundable if the account is banned. However, this is not a true crypto-economic model in practice, as the primary barrier to creating new accounts is not the need to pay $10 again, but rather obtaining a new credit card.

In theory, payments could even be made conditional: when registering an account, you would only need to stake a sum of money, which would only be lost in the rare case of the account being banned. Theoretically, this could significantly increase the cost of attacks.

This solution works effectively in many scenarios, but it is completely unworkable in certain types of situations. I will focus on two types of scenarios, tentatively referred to as "UBI-like" and "governance-like" scenarios.

The Need for Identity in UBI-like Scenarios

The so-called "UBI-like scenarios" refer to situations where a certain amount of assets or services needs to be distributed to a very broad (ideally, the entire) user base, regardless of their ability to pay. Worldcoin systematically practices this: anyone with a World ID can regularly receive a small amount of WLD tokens. Many token airdrops also aim to achieve similar goals in a more informal manner, attempting to ensure that at least some tokens reach as many users as possible.

Personally, I do not believe that the value of such tokens can reach a level sufficient to sustain a person's livelihood. In an AI-driven economy with wealth scales reaching current multiples, such tokens might have the value to sustain a living; however, even then, government-led projects supported by natural resource wealth would still hold a more significant economic position. Nevertheless, I believe that these "mini-UBIs" can effectively solve the problem of providing people with enough cryptocurrency to complete some basic on-chain transactions and online purchases. This could specifically include:

- Acquiring an ENS name

- Publishing a hash on-chain to initialize a zero-knowledge proof identity

- Paying fees on social media platforms

If cryptocurrency were widely adopted globally, this issue would no longer exist. However, in the current context where cryptocurrency is not yet mainstream, this may be the only way for people to access non-financial on-chain applications and related online goods and services; otherwise, they might be completely cut off from these resources.

Additionally, there is another way to achieve a similar effect, namely "universal basic services": providing every person with an identity the ability to send a limited number of free transactions within specific applications. This approach may align better with incentive mechanisms and be more capital-efficient, as each application benefiting from this adoption can do so without paying for non-users; however, this also comes with certain trade-offs, namely a reduction in universality (users can only ensure access to applications participating in the program). Even so, a set of identity solutions is still needed to prevent the system from suffering from spam attacks while avoiding exclusivity, which arises from requiring users to pay through certain payment methods that may not be accessible to everyone.

The last important category worth emphasizing is the "universal basic security deposit." One of the functions of identity is to provide a target for accountability without requiring users to stake funds equivalent to the scale of incentives. This also helps achieve a goal: reducing the reliance on individual capital amounts for participation (or even requiring no capital at all).

The Need for Identity in Governance-like Scenarios

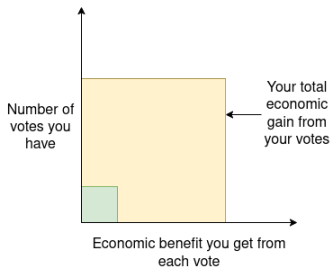

Imagine a voting system (for example, likes and shares on a social media platform): if user A has resources that are 10 times greater than user B's, then A's voting power will also be 10 times that of B's. However, from an economic perspective, each unit of voting power brings A 10 times the benefit it brings B (because A's scale is larger, any decision's impact on A's economic situation will be more significant). Therefore, overall, A's voting benefits are 100 times greater than B's. This is why we find that A will invest much more effort in voting, researching how to vote to maximize their own goals, and may even strategically manipulate algorithms. This is also the fundamental reason why "whales" can exert excessive influence in token voting mechanisms.

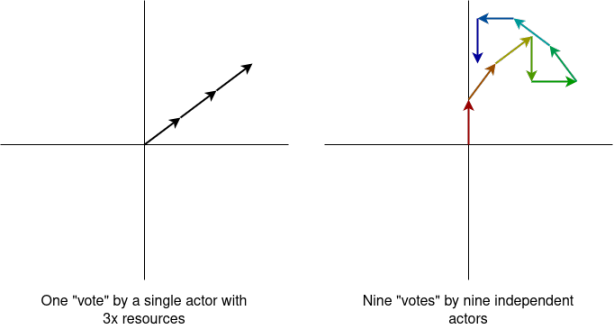

A more universal and deeper reason is that governance systems should not assign equal weight to "one person controlling $100,000" and "1,000 people collectively holding $100,000." The latter represents 1,000 independent individuals, thus containing richer valuable information rather than a high degree of repetition of small-scale information. Signals from 1,000 people are also often more "moderate," as differing opinions tend to cancel each other out.

This applies to both formal voting systems and "informal voting systems," such as people's ability to participate in cultural evolution through public expression.

This indicates that governance-like systems will not be truly satisfied with the approach of "regardless of the source of funds, all funds of equal scale are treated equally." The system actually needs to understand the internal coordination level of these bundles of funds.

It is important to note that if you agree with my framework for describing the above two types of scenarios (UBI-like scenarios and governance-like scenarios), then from a technical perspective, the need for a clear rule of "one person, one vote" no longer exists.

- For UBI-like applications, the identity solution truly needed is: the first identity is free, with limits on the number of identities that can be obtained. When the cost of obtaining more identities is high enough to render the act of attacking the system meaningless, the limiting effect is achieved.

- For governance-like applications, the core requirement is: the ability to judge through some indirect indicators whether the resource you are dealing with is controlled by a single entity or a "naturally formed," loosely coordinated group.

In both scenarios, identity remains very useful, but the requirement for strict rules like "one person, one identity" is no longer necessary.

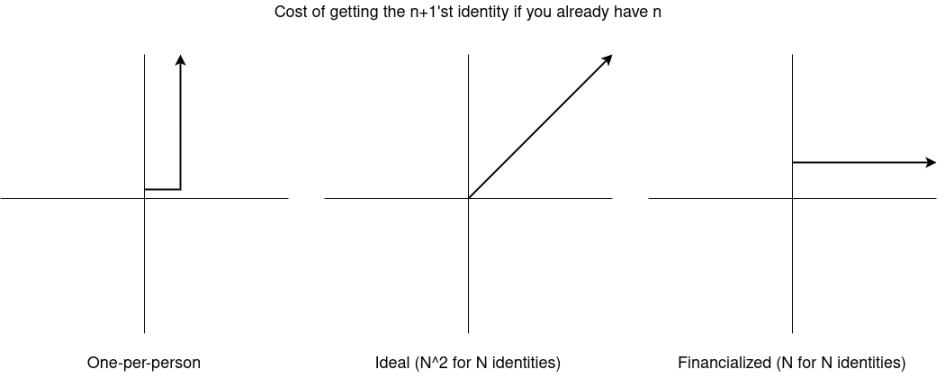

The Theoretical Ideal State: The Cost of Obtaining N Identities is N²

From the arguments above, we can see that two pressures from opposite ends limit the expected difficulty of obtaining multiple identities within identity systems:

First, there cannot be a clear and visible hard limit on "the number of easily obtainable identities." If a person can only have one identity, then anonymity cannot be discussed, and they may be coerced into revealing their identity. In fact, even a fixed number greater than 1 carries risks: if everyone knows that each person has 5 identities, you may be coerced into revealing all 5.

Another reason supporting this is that anonymity itself is fragile, thus requiring a sufficiently large security buffer. With modern AI tools, cross-platform association of user behavior has become effortless; through publicly available information such as word usage patterns, posting times, posting intervals, and discussion topics, as little as 33 bits of information can accurately pinpoint an individual. People might use AI tools for defense (for example, when I anonymously posted content, I first wrote it in French and then translated it into English using a locally running large language model), but even so, one mistake could completely end their anonymity.

Second, identities cannot be entirely tied to finances (i.e., the cost of obtaining N identities is N), as this would allow large entities to easily gain excessive influence (leading to small entities completely losing their voice). The new mechanism of Twitter Blue exemplifies this: the $8 monthly certification fee is too low to effectively limit abuse, and users have essentially become indifferent to this certification mark.

Moreover, we may not want entities with resources N times greater to be able to act with impunity, committing N times the inappropriate behavior.

In summary, we hope to obtain multiple identities as easily as possible while satisfying the following constraints: (1) limiting the power of large entities in governance applications; (2) limiting abuse in UBI applications.

If we directly borrow the mathematical model from governance applications mentioned earlier, we arrive at a clear answer: if having N identities brings N² influence, then the cost of obtaining N identities should be N². Coincidentally, this answer also applies to UBI applications.

Old readers of this blog may notice that this aligns perfectly with a chart from an earlier post on "quadratic funding," and this is not a coincidence.

Pluralistic Identity Systems Can Achieve This Ideal State

The so-called "pluralistic identity system" refers to an identity mechanism that does not have a single dominant issuing entity, whether that entity is an individual, organization, or platform. This system can be realized in two ways:

- Explicit pluralistic identity. You can verify your identity (or other claims, such as confirming you are a member of a community) through the proof of others in your community, and these verifiers' identities are also validated through the same mechanism. The article "Decentralized Society" provides a more detailed explanation of this design, and Circles is currently a running example.

- Implicit pluralistic identity. This is the current state, where there are many different identity providers, including Google, Twitter, similar platforms in various countries, and various government-issued identification documents. Very few applications accept only one type of identity verification; most applications will accommodate multiple types, as this is the only way to reach potential users.

A recent snapshot of the Circles identity graph. Circles is currently one of the largest social-graph-based identity projects.

Explicit pluralistic identities naturally possess anonymity: you can have an anonymous identity (or even multiple), each of which can build a reputation in the community through its actions. An ideal explicit pluralistic identity system might not even require the concept of "discrete identities"; instead, you might possess a fuzzy set composed of verifiable past behaviors and be able to prove different parts of it in a refined manner based on the needs of each action.

Zero-knowledge proofs will make anonymity easier to achieve: you can use your main identity to initiate an anonymous identity, providing the first signal privately to gain recognition for the new anonymous identity (for example, by using zero-knowledge proofs to show you possess a certain amount of tokens, allowing you to post content on anon.world; or by using zero-knowledge proofs to demonstrate that your Twitter followers possess certain characteristics). There may also be more effective ways to use zero-knowledge proofs.

The "cost curve" of implicit pluralistic identities is steeper than a quadratic curve, but still possesses most of the required characteristics. Most people have some forms of identity listed in this article, rather than all of them. You can obtain another form of identity with some effort, but the more forms of identity you have, the lower the cost-effectiveness ratio for obtaining the next one becomes. Therefore, it provides the necessary deterrent against governance attacks and other abusive behaviors, while ensuring that coercers cannot demand (and cannot reasonably expect) you to disclose a fixed set of identities.

Any form of pluralistic identity system (whether implicit or explicit) naturally has stronger fault tolerance: a person with a hand or eye disability may still hold a passport, and stateless individuals may still prove their identity through certain non-governmental channels.

It is important to note that if a certain form of identity approaches a market share of 100% and becomes the only login option, the above characteristics will fail. In my view, this is the greatest risk that identity systems overly focused on "universality" may face: once their market share approaches 100%, it will push the world from a pluralistic identity system to a "one person, one identity" model, which, as discussed in this article, has many drawbacks.

In my opinion, the ideal outcome for current "one person, one identity" projects is to merge with social-graph-based identity systems. The biggest problem faced by social-graph-based identity projects is the difficulty in scaling to a massive user base. The "one person, one identity" system can be used to provide initial support for the social graph, creating millions of "seed users," at which point the user base will be large enough to safely develop a globally distributed social graph from this foundation.

Recommended reading:

7 personnel adjustments, three new organizations, can Ethereum's "self-rescue" be reborn?

Vitalik's new article: How does Ethereum achieve a simplified architecture comparable to Bitcoin?

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。