Explore how to create a truly effective public goods funding system.

Author: Carl Cervone

Translator: Elsa

Translator's Preface

In this article, the author uses the concept of "Circles" as a starting point to progressively reveal how we often only focus on the circles we are in in our daily lives, often using distance as an excuse to overlook funding for public goods outside of our circles. The article also further explores how to expand the funding mechanism for public goods to a broader scope, beyond the circles we directly interact with, to create a truly effective public goods funding system. Through such expansion, we can build a "diverse, civilized-scale public goods funding infrastructure."

Main Content

This article is inspired by the work and thought leadership of organizations mentioned in the text (such as Gitcoin, Optimism, Drips, Superfluid, Hypercerts), as well as multiple conversations with Juan Benet and Raymond Cheng about the characteristics of network capital and private capital.

Every funding ecosystem has a core area and important but peripheral areas

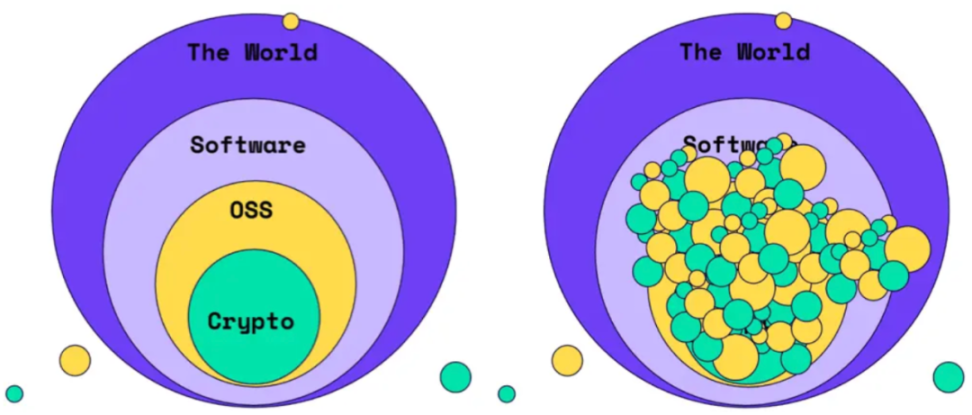

Gitcoin visualized the concept of Nested Scopes well in a blog post in 2021. The original text describes a series of influences on the funding mechanism, initially focused on the inner circle ("crypto"), then expanding to the next circle ("open-source software"), and ultimately influencing the entire world.

Owocki's illustration shows the evolution of the impact of native crypto on the funding mechanism, gradually expanding to influence the entire world.

This is a good point: start by solving problems near home, then scale up.

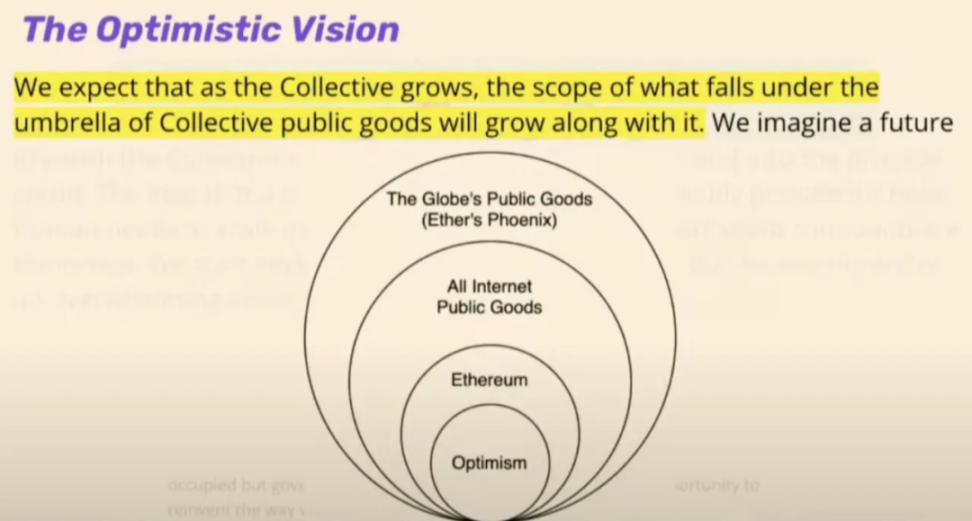

Optimism also explains its vision for retroactive public goods funding from a similar perspective.

Optimism's vision is to expand the scope of supporting public goods through retroactive funding.

Optimism is within Ethereum, and Ethereum is within "all internet public goods." "All internet public goods" are within "global public goods." Each outer domain is a superset of its inner domain.

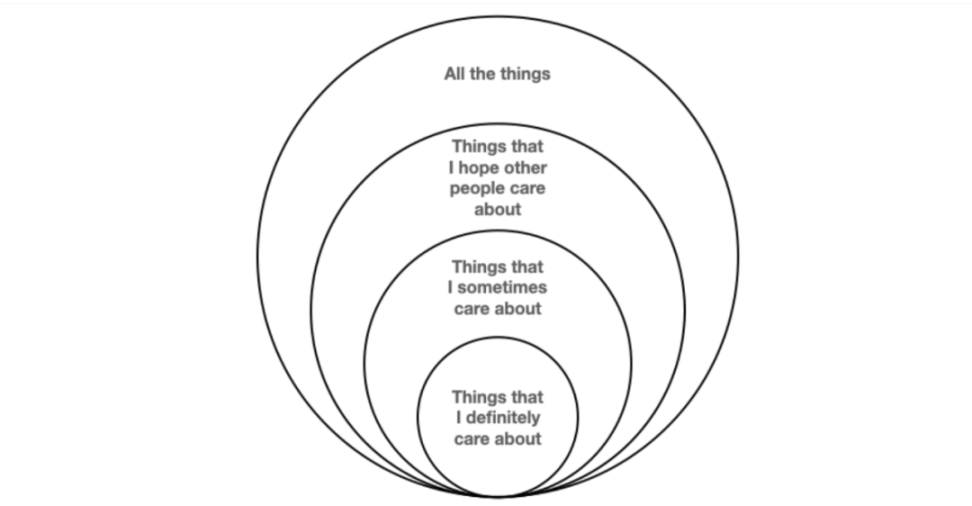

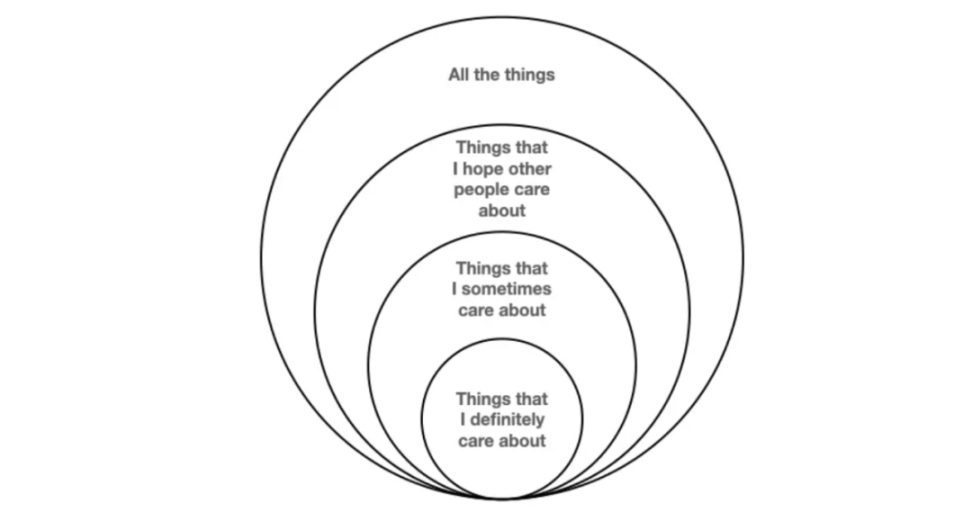

Here is my summary version of these four concentric circle memes.

I care about "everything," but I don't want to worry about how they get funded.

Although I personally may not spend time considering deep-sea biodiversity or noise pollution in Kolkata, many people do care about these issues. Simply being aware of something often shifts it from "everything" to "things I hope others care about" in this circle.

Most of us lack the ability to evaluate important matters outside our immediate circles

We can usually reasonably evaluate things closely related to our daily lives. This is our inner circle, or things we truly care about.

In an organization, one's inner circle may include your teammates, projects you closely collaborate on, and tools you frequently use.

We can also evaluate some (but maybe not all) things one degree upstream or downstream from our daily circles. These are things we sometimes care about.

In the case of a software package, upstream may include your dependencies, and downstream may include projects that depend on your software package. In an educational course, upstream may include valuable courses or resources that influence the course, and downstream may include students recommending the course to friends.

Whether a software developer or an educator, they can seek upstream research and the institutions responsible for it. Now we are entering the domain of caring about "everything."

However, most rational people would stop caring too much about anything at this point. Once we go beyond one degree, things become blurry. These are things we hope others care about.

The risk is that we may use distance as an excuse to not fund these things, exacerbating the free-rider problem

While all matters in our inner circle depend on good funding support from the outer circle, it is difficult to contribute beyond one's "fair share" of funding for matters one circle away (although some may attempt to calculate this share). There are valid reasons for this.

First, categorizing in large domains is difficult. Categories like "all internet public goods" are too broad, to the point where you could argue that almost anything could be included and worthy of funding support from a different perspective.

Second, it is difficult to incentivize stakeholders to care about matters outside their circles because the impact is so dispersed. I would rather fund the entire team I know than an unknown part of a team I don't know.

Finally, not funding these projects does not have direct consequences—of course, assuming others continue to fund them and do not drop out.

So, we encounter the typical free-rider problem.

Apart from governments being able to pay for long-term public goods projects through printing money, taxation, and issuing bonds, as a society, we lack a good mechanism to fund things just beyond our immediate circles. Most capital is used for things with short-term returns and closer impacts.

One way to address this problem is to have people focus on funding things they are closely related to (things they can personally evaluate) and establish mechanisms to continuously push some funds to peripheral areas.

By the way, this is exactly how private capital flows. We should try to emulate some characteristics of private capital.

The risk investment model for things with no short-term/medium-term returns is effective because private capital is composable and easily divisible

There is a model for funding hard tech with a return cycle of 5 to 10 years or more: it's called venture capital. Of course, in any given year, the scale of funds flowing to long-term projects is more influenced by interest rates than final value. But looking at the ability to attract and mobilize trillions of dollars over the past few decades, venture capital is a proven effective model.

The model is effective largely because venture capital (and other sources of investment capital) is composable and easily divisible.

By composable, I mean you can accept venture capital funds while also going public, obtaining bank loans, issuing bonds, and raising capital through more exotic mechanisms. In fact, this is expected. All these financing mechanisms are interoperable.

These mechanisms are well composed because there are clear commitments about who owns what and how cash is allocated. In fact, most companies use a range of financing tools throughout their lifecycle.

Investment capital is also easily divisible. Many people contribute to the same pension fund. Many pension funds (and other investors) invest in the same venture capital fund. Many venture capital funds then invest in the same company. All these divisions occur upstream of the daily affairs of companies.

These characteristics make the flow of private capital in a complex network very efficient. If a company supported by venture capital has a liquidity event (such as an IPO, acquisition, etc.), the returns are efficiently distributed among the company and its venture capital firms, the venture capital firms and their limited partners, the pension funds and their retirees, and even from retirees to their children.

This is not how public goods funding flows in networks. Instead of numerous irrigation channels, we have relatively few large water towers (such as governments, large foundations, high-net-worth individuals, etc.).

Private Capital vs. Public Capital Flow

To be clear, I am not advocating for public goods to receive venture capital funding. I am simply pointing out two important characteristics of private capital that do not have corresponding features in public capital.

How can we make more public goods funding flow beyond our immediate circles

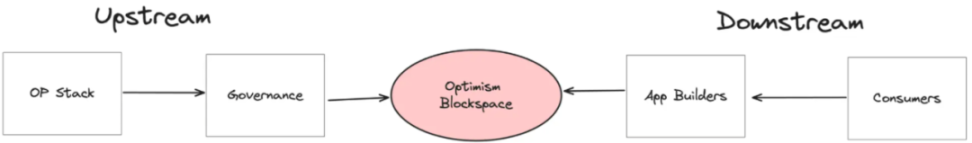

Optimism recently announced a new plan for retroactive funding within its ecosystem.

In the previous round of Optimism's retroactive funding, the range of projects that could be funded was very broad. In the foreseeable future, the scope of funding will be much narrower, focusing on the upstream and downstream links closer to its value chain.

How Optimism is currently considering upstream and downstream impacts

It is not surprising that there is varied feedback on these changes, with many projects that were previously within the funding scope now being excluded from upcoming rounds.

In the newly announced first round of funding, "on-chain builders" were allocated 10 million tokens, while in the third round of funding, the allocation for on-chain builders disproportionately decreased—out of a competitive 30 million tokens, only about 1.5 million tokens were available. How will these projects utilize this funding if they receive retroactive funds 2-5 times more than the 1.5 million tokens?

One thing they can do is allocate some tokens to their own retroactive funding or funding rounds.

Specifically, if Optimism funds DeFi applications that drive network transaction volume, these applications can fund front-end, portfolio trackers, and other applications serving the impacts they care about.

If Optimism funds dependencies at the core of the OP stack, these teams can fund their own dependencies, research contributions, and more.

What if projects utilize the retroactive funds they believe they deserve and allocate the rest into circulation?

This has already happened in various forms. The Ethereum Attestation Service now has a scholarship program set up for teams building on its protocol. Pokt has just announced its own retroactive funding rounds, integrating all tokens received from Optimism (and Arbitrum) into this round. Even Kiwi News, which received below-median funding in the third round, has implemented its own version of retroactive funding for community contributions.

Meanwhile, Degen Chain has pioneered a more aggressive concept, giving community members token allocations and requiring them to gift these tokens to other community members as "tips."

All these experiments are guiding public goods funding from central pools (such as OP or Degen treasuries) to the periphery, expanding their impact.

The next step is to make these commitments explicit and verifiable.

One way to do this might be for projects to determine a floor value and a percentage above the floor they are willing to allocate to their own funding pool. For example, perhaps my floor value is 50 tokens, and I am willing to allocate 20% above the floor value. If I receive a total of 100 tokens, I will allocate 10 tokens (20% above the floor value of 50 tokens) to fund the periphery of my network. If I only receive 40 tokens, I will retain all 40 tokens.

(By the way, my project has also done something similar in the previous round of Optimism funding.)

In addition to pushing more funds to the periphery, this also serves a crucial role in helping public goods projects establish a cost basis. In the long run, for projects that consistently receive lower-than-expected funding, the message conveyed is: they are underpricing their work or undervalued in the funding ecosystem.

Projects with surpluses in subsequent rounds will be evaluated not only based on their own impact but also on the broader impact they create through good capital allocation. Projects that do not want to run their own funding programs can choose to park their surplus in other productive places, such as the Gitcoin matching pool, Protocol Guild, or even choose to burn these surpluses!

In my view, the values determined by projects before receiving funding should be kept confidential. If a project receives 100 tokens and donates 10 tokens, others should not know whether their values are (50, 20%) or (90, 100%).

The final step is to connect these systems.

Examples like EAS, Pokt, and Kiwi News are inspiring, but they all require setting up new projects, then applying/exchanging/transferring funding tokens to new wallets, and ultimately transferring funds to new beneficiaries.

Protocols like Drips, Allo, Superfluid, and Hypercerts provide the underlying infrastructure for more composable funding flows—now we need to connect these pipelines, just like this pilot project from Geo Web.

The task of this cycle is to create a truly effective public goods funding system. Then, we begin to promote it.

In the crypto space, we are still in the stage of experimenting with various mechanisms to determine which projects to fund and how to allocate funds. The infrastructure for public goods funding is still not mature enough, lacks composability, and lacks real-world testing compared to decentralized finance (DeFi).

To move beyond the experimental stage and achieve scalability, we need to address two issues:

Measurement: not only proving that these mechanisms are effective but also demonstrating that they are more effective than traditional public goods funding models (see this post [1] for why this is an important issue worth striving for, and another post [2] for an analysis of Gitcoin's long-term impact).

Explicit commitments: clear commitments about how "profits" or surplus funds flow to external circles.

In venture capital, there is always an investor behind the investor—ultimately, this could be your grandmother (more accurately, all of our grandmothers). Each such investor is incentivized to allocate capital effectively so that they can be trusted in the future and have more control over capital allocation.

For public goods, there is always a closely related set of participants, whether upstream or downstream of your work, that you depend on. But currently, there are no commitments to share these surpluses with these entities. Until such commitments become the norm, public goods funding will struggle to move beyond our immediate circles and achieve scalability.

We have not yet reached the stage of being better than the traditional model (image from the Gitcoin whitepaper)

I believe it is not enough to simply commit to "we will fund these projects when we reach a certain scale." This is too easily changeable. Instead, these commitments need to be established early on, integrated as foundational elements into the funding mechanisms and allocation projects being built.

I believe it is unreasonable to expect a few whales' treasuries to fund everything. This is the water tower model we adopt in traditional governments and large foundations.

But if we make explicit commitments to provide funding for our dependencies when we are still small, it will demonstrate the existence of a public goods market, expand the total addressable market (TAM), and change the incentive mechanism.

Only in this way can we have something truly worth promoting, something that can build its own momentum and create the "diversified, civilized-scale public goods funding infrastructure" we dream of.

References

[1] Building a network of Impact Data Scientists. Retrieved from https://docs.opensource.observer/blog/impact-data-scientists/.

[2] A longitudinal assessment of Gitcoin Grants impact on open source developer activity. Retrieved from https://docs.opensource.observer/blog/gitcoin-grants-impact/.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。