Understanding the design ideas of the new generation of Bitcoin cross-chain bridges from Bitlayer and Citrea.

Author: Faust & Nickqiao, Geek Web3

Abstract:

The ZK bridge deploys smart contracts on chain A, directly receives and verifies the block headers of chain B and the corresponding zero-knowledge proofs, confirms the validity of cross-chain messages, and is the highest level of security for bridge solutions. The optimistic/OP bridge uses fraud proofs to challenge invalid cross-chain messages on-chain. With just one reliable challenger, the security of the cross-chain bridge fund pool can be ensured.

Due to technical limitations, the Bitcoin mainnet cannot directly deploy the ZK bridge, but can achieve an optimistic bridge through BitVM and fraud proofs. Teams such as Bitlayer and Citrea have adopted the BitVM bridge solution, introducing pre-signing and combining the concept of channels, allowing users to limit the post-deposit processing before the formal deposit, preventing the official cross-chain bridge from misappropriating user deposits.

The BitVM bridge is essentially based on the "advance payment - reimbursement" model, with dedicated Operator nodes to pay withdrawal users, and Operators can regularly apply for reimbursement from the public deposit address. If the Operator makes false reimbursement claims, anyone can challenge and slash them.

The BitVM bridge theoretically has no security issues, but has liveness/availability issues, and cannot meet specific user needs for fund independence and anti-money laundering (essentially still a fund pool model). Bitlayer has added an OP-DLC bridge solution, which is similar to DLC.link, introducing fraud proofs based on channels and DLC to prevent malicious behavior by the DLC bridge's oracle.

Due to the difficulty of implementing BitVM and fraud proofs, the DLC bridge will be the first to be implemented and serve as a temporary substitute, as long as the trust risk of the oracle is resolved and more reliable and mature third-party oracles are integrated, the DLC bridge can become a more secure withdrawal verification solution than the multi-signature bridge at the current stage.

Preface

Since the craze for Layer2 solutions for Bitcoin last year, the Bitcoin ecosystem has entered a period of rapid growth. In just half a year, nearly 100 projects claiming to be BTC Layer2 solutions have emerged, creating a chaotic landscape where opportunities and scams coexist. It has become a melting pot of various ethnicities in the Bitcoin ecosystem, alongside Ethereum, Cosmos and Celestia, CKB, and the Bitcoin native ecosystem. The lack of authoritative voices has turned the Bitcoin ecosystem into a new frontier attracting various forces. While this has brought prosperity and vitality to the entire Web3 narrative, it has also introduced significant risks.

Many projects have been hyping up without even releasing their technical solutions, claiming to fully inherit the security of the Bitcoin mainnet under the guise of native Layer2. Some have even resorted to creating conceptual propaganda, inventing a plethora of bizarre terminology to promote their own superiority. Although self-promotion has become the current state of the Bitcoin ecosystem, many top KOLs have issued objective criticisms.

Not long ago, Monanaut, the founder of the blockchain explorer Mempool, publicly criticized the current issues in the Bitcoin ecosystem, sharply pointing out that if a Bitcoin Layer2 solely relies on a multi-signature withdrawal bridge, it cannot allow users to withdraw assets at any time in a trustless manner, then such a project is not a true Layer2. Interestingly, Vitalik had previously pointed out that Layer2 should at least be more secure in terms of security than systems solely relying on multi-signatures.

It can be said that Monanaut and Vitalik have bluntly pointed out the technical issues of Bitcoin Layer2: many Layer2 withdrawal bridges are essentially multi-signature bridges, either with several well-known institutions each holding a key, or using decentralized signatures based on POS. However, in any case, their security model is based on the assumption of majority honesty, assuming that the majority of the multi-signature participants are not colluding maliciously.

This heavy reliance on credit endorsement for withdrawal bridge solutions is not a long-term strategy. History has shown us that multi-signature bridges will inevitably encounter various problems. Only asset custody methods that minimize trust or tend towards complete trustlessness can withstand the test of time and hackers. However, the current state of the Bitcoin ecosystem is that many project teams have not even released a technical roadmap for their withdrawal bridges, and there is no established design approach for how to minimize trust or achieve trustlessness for the bridges.

However, this does not represent the entire Bitcoin ecosystem. Some project teams have expressed their opinions on optimizing withdrawal bridge solutions. In this article, we will briefly analyze the BitVM bridge from Bitlayer and Citrea, and introduce Bitlayer's OP-DLC bridge proposed to address the shortcomings of the BitVM bridge, allowing more people to understand the risks and design ideas of cross-chain bridges, which is crucial for the vast participants in the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Optimistic Bridge: A Verification Solution Based on Fraud Proofs

In fact, the essence of a cross-chain bridge is simple: it is to prove to chain B that a certain event has indeed occurred on chain A. For example, if you want to cross assets from ETH to Polygon, you need the cross-chain bridge to prove that you have indeed transferred assets to a specific address on the ETH chain, and then you can receive an equivalent amount of funds on the Polygon chain.

Traditional cross-chain bridges generally use multi-signature witnesses. They will designate several witnesses off-chain, and these witnesses need to run nodes for various public chains to monitor whether anyone has deposited funds into the cross-chain bridge's receiving address.

The security model of these cross-chain bridges is basically the same as that of multi-signature wallets. It follows a multi-signature setting method such as M/N to determine its trust model, but ultimately it mostly follows the assumption of majority honesty, assuming that the majority of notaries are not malicious, with limited fault tolerance. Many large-scale theft cases involving cross-chain bridges have occurred with these multi-signature bridges, either due to self-embezzlement or hacker attacks.

In comparison, "optimistic bridges" based on fraud-proof protocols, and "ZK bridges" based on zero-knowledge proofs, are much safer. Taking the ZK bridge as an example, it deploys a dedicated verifier contract on the target chain to directly verify the withdrawal proof on-chain, eliminating the need to rely on off-chain witnesses.

For example, a ZK bridge spanning ETH and Polygon will deploy a verifier contract on Polygon, referred to as Verifier. The Relayer node of the ZK bridge will forward the latest Ethereum block header and the validity proof ZK Proof to the Verifier on Polygon, which will then verify them. This is equivalent to allowing the Verifier contract to synchronize and verify the latest Ethereum block header on the Polygon chain. The merkle root recorded on the block header is related to the set of transactions contained in the block and can be used to verify whether a specific transaction is included in the block.

If, for example, there are 10 cross-chain transfer declarations from ETH to Polygon in an Ethereum block at height 101, the Relayer will generate a Merkle Proof related to these 10 transactions and submit the proof to the Verifier contract on the Polygon chain.

101 transactions of ETH to Polygon are included in Ethereum block number 101. Of course, the ZK bridge can ZK-proof the Merkle Proof and directly submit the ZK Proof to the Verifier contract. In this entire process, users only need to trust that the cross-chain bridge's smart contract is free of vulnerabilities and that the zero-knowledge proof technology itself is secure and reliable, without the need to introduce excessive trust assumptions like traditional multi-signature bridges.

However, the "Optimistic Bridge" is slightly different. Some optimistic bridges retain settings similar to witnesses but introduce fraud proofs and challenge windows. After the witnesses generate a multi-signature for the cross-chain message, although it is submitted to the target chain, its validity is not immediately recognized and must pass a window period without challenge before being deemed valid. This is actually somewhat similar to the approach of Optimistic Rollup. Of course, optimistic bridges have other product models, but ultimately, security is guaranteed by fraud-proof protocols.

The trust assumption of an M/N multi-signature bridge is N-(M-1)/N, where you assume that the maximum number of malicious actors in the network is M-1, and the minimum number of honest actors is at least N-(M-1). The trust assumption of a ZK bridge can be ignored, while for an optimistic bridge based on fraud proofs, the trust assumption is 1/N. Among N witnesses, only one honest witness willing to challenge invalid cross-chain messages submitted to the target chain is needed to ensure the bridge's security.

Currently, due to technical limitations, only the deposit direction from Bitcoin to Layer2 can be implemented with a ZK bridge. If the direction is reversed, from Layer2 to the Bitcoin chain for withdrawals, only multi-signature bridges or optimistic bridges are supported, or a mode similar to channels (the upcoming OP-DLC bridge is more like a channel). To implement an optimistic bridge on the Bitcoin chain, fraud proofs need to be introduced, and BitVM has created favorable conditions for this technology.

In a previous article "A Simple Explanation of BitVM: How to Verify Fraud Proofs on the BTC Chain", we briefly explained that BitVM's fraud proof essentially breaks down complex off-chain computing tasks into numerous simple steps, and then selects a specific step to be directly verified on the Bitcoin chain. This approach is similar to Arbitrum, Optimism, and other Ethereum optimistic rollup solutions.

Of course, the above explanation may be somewhat obscure, but it is believed that most people already have some understanding of fraud proofs. In today's article, due to the overall length, we do not intend to interpret the technical implementation details of BitVM and the fraud proof protocol, as this involves a series of complex interaction processes.

We will briefly introduce the native BitVM bridge designed by BitLayer, Citrea, BOB, and the official BitVM design, as well as how Bitlayer alleviates the bottleneck of the BitVM bridge through the OP-DLC bridge from the perspective of product and mechanism design, to show how a superior withdrawal bridge solution can be designed on the Bitcoin chain.

Bitlayer and Citrea's BitVM Bridge Principle Brief Analysis

In the following text, we will use the publicly disclosed BitVM bridge solutions from Bitlayer, Citrea, and Bob as material to explain the general operation process of the BitVM bridge.

In their official documentation and technical blogs, the above project teams have provided a clear explanation of the product design approach for the BitVM withdrawal bridge (currently in the theoretical stage). First, when a user withdraws funds through the BitVM bridge, they need to use the Bridge contract on Layer2 to generate a withdrawal declaration. The withdrawal declaration will specify the following key parameters:

The amount of mapped BTC to be destroyed on L2 by the withdrawal person (e.g., 1 BTC);

The cross-chain transaction fee the withdrawal person intends to pay (assumed to be 0.01 BTC);

The receiving address of the withdrawal person on L1: L1_receipt;

The amount to be received by the withdrawal person (i.e., 1 - 0.01 = 0.99 BTC)

Subsequently, the above withdrawal declaration will be included in the Layer2 block. The Relayer node of the BitVM bridge will synchronize the Layer2 block, monitor the included withdrawal declarations, and forward them to the Operator node, which will then make the payment to the withdrawal user.

It is important to note that the Operator first pays the withdrawal user on the Bitcoin chain out of their own pocket, essentially "advancing" the funds for the BitVM bridge, and then applies for reimbursement from the BitVM bridge's fund pool.

When applying for reimbursement, the Operator needs to provide proof of their advance payment on the Bitcoin chain (i.e., proof that they made the payment to the withdrawal user's specified address on L1, extracting the specific transfer record included in the Bitcoin block). At the same time, the Operator also needs to provide the withdrawal declaration generated by the withdrawal person on L2 (using a Merkle Proof to prove that the provided withdrawal declaration comes from the L2 block and is not fabricated out of thin air by the Operator). Subsequently, the Operator needs to prove the following:

The funds advanced by the Operator for the BitVM bridge to the withdrawal person are equal to the amount requested by the withdrawal person in the declaration;

When applying for reimbursement, the reimbursement amount does not exceed the amount of mapped BTC destroyed by the withdrawal person on Layer2;

The Operator has indeed processed all the L2-L1 withdrawal declarations over a period of time, and each withdrawal declaration can be matched to the withdrawal transfer record on the Bitcoin chain;

This essentially serves as a penalty for the Operator for falsely reporting the amount advanced or refusing to process withdrawal declarations (which can address the issue of censorship resistance for the withdrawal bridge). The Operator needs to compare and verify the key fields of the advance payment proof and the withdrawal declaration off-chain, proving that the BTC amounts involved are equal.

This concludes the translation of the provided text.

If the withdrawal bridge Operator falsely reports the amount advanced, it means that the Operator claims that the payment proof on L1 matches the Withdrawal Statement issued by the withdrawal person on L2, but in reality, the two do not match.

In this case, it is certain that the ZKP proving Payment Proof = Withdrawal Statement is incorrect. As soon as this ZKP is published, the Challenger can point out which step is incorrect and challenge it through BitVM2's fraud-proof protocol.

It is important to emphasize that Bitlayer, Citrea, BOB, ZKBase, and others have adopted the latest BitVM2 route, which is the new version of the BitVM solution. This approach involves ZK-proving off-chain computing tasks, meaning that the computing process generates ZK Proof, which is then verified. The verification process is then transformed into a form compatible with BitVM, making it easier for subsequent challenges.

At the same time, by using Lamport and presigning, the original multi-round interactive challenge of BitVM has been optimized to a single-round non-interactive challenge, greatly reducing the difficulty of challenges.

The challenge process of BitVM requires the use of something called "Commitment." Let's explain what "Commitment" is. Generally, when a "Commitment" is published on the Bitcoin chain, the person claims that certain off-chain data or computing tasks are accurate, and the related declarations published on the chain are the "Commitment."

We can roughly understand Commitment as the hash of a large amount of off-chain data. The size of the Commitment itself is often compressed very small, but it can be bound to a large amount of off-chain data through methods such as Merkle Tree, and this associated off-chain data does not need to be put on the chain.

In the BitVM2, Citrea, and BitLayer BitVM bridge solutions, if someone believes that the Commitment published by the withdrawal bridge Operator on the chain is problematic and associated with an invalid ZKP verification process, they can initiate a challenge, and the challenge permission is Permissionless. (The interaction process inside is quite complex and will not be explained here.)

Since the Operator advances funds from the BitVM fund pool to make payments to the withdrawal person, and then applies for reimbursement from the fund pool, when applying, the Operator needs to publish a Commitment to prove that the money transferred to the withdrawal person on L1 is equal to the amount declared by the withdrawal person on L2. If this Commitment is not challenged after the fraud-proof window period, the Operator can take the reimbursement amount they need.

Here we need to explain how the public fund pool of the BitVM bridge is maintained, which is the most critical part of a cross-chain bridge. As we all know, the funds that the cross-chain bridge can pay to the withdrawal person come from the deposits of depositors or other LP-contributed assets. The money advanced by the Operator ultimately needs to be withdrawn from the public fund pool, so simply looking at the transfer result of the funds, the amount deposited by depositors into the BitVM bridge should be equal to the amount withdrawn by the withdrawal person. Therefore, how to safeguard the deposited funds is a very important issue.

In most Bitcoin Layer2 bridge solutions, public assets are often managed through multi-signature, where user deposits are aggregated into a multi-signature account, and when it is necessary to make payments to the withdrawal person, this multi-signature account is responsible for making the payment. This approach obviously carries significant trust risks.

Bitlayer and Citrea's BitVM bridge, however, adopts a similar approach to the Lightning Network and channels. Before depositing, users communicate with the BitVM alliance to obtain a presignature, achieving the following effect:

After depositing funds into the deposit address, this money is directly locked in a Taproot address and can only be claimed by the Operator of the bridge. Moreover, the Operator can only claim the funds from the above-mentioned deposit Taproot address after advancing the withdrawal funds to the user and applying for reimbursement. After the challenge period ends, the Operator can then withdraw a certain amount of the user's deposit.

In the BitVM bridge solution, there is a BitVM alliance composed of N members, responsible for managing user deposits. However, these N members cannot misappropriate user deposits on their own, because before making payments to the specified address, users require the BitVM alliance to presign, ensuring that these deposits can only be legitimately claimed by the Operator.

In summary, the BitVM bridge adopts a similar approach to channels and the Lightning Network, allowing users to "verify by yourself" and preventing the BitVM alliance from manipulating the deposit pool on its own through presigning. The funds in the deposit pool can only be used for reimbursing the Operator. If the Operator falsely reports the amount advanced, anyone can publish a fraud proof and challenge it.

If the above solution can be implemented, the BitVM bridge will become one of the safest Bitcoin withdrawal bridges: this bridge does not have security issues, only availability/liquidity issues. When users attempt to deposit funds into BitVM, they may face scrutiny or lack of cooperation from the BitVM alliance, leading to the inability to deposit funds smoothly, but this is not related to security and falls under the category of availability/liquidity issues.

However, the implementation difficulty of the BitVM bridge is quite high, and it also cannot meet the needs of large holders who require high transparency of funds: these individuals may be involved in anti-money laundering issues and may not want to mix their funds with others. However, the BitVM bridge consolidates the deposits of depositors, to some extent creating a pool of mixed funds.

To address the availability issues of the BitVM bridge and provide a clean and independent fund entry and exit channel for those with specific needs, the BitLayer team has additionally added a cross-chain bridge solution called OP-DLC, which, in addition to the optimistic bridge of BitVM2, adopts a DLC bridge similar to DLC.link. This provides users with two entry and exit points for the BitVM bridge and OP-DLC bridge, reducing dependence on the BitVM bridge and even the BitVM alliance.

DLC: Discreet Log Contracts

DLC (Discreet Log Contracts) is a privacy-focused smart contract proposed by MIT's Digital Currency Initiative. This technology was initially used to implement a lightweight smart contract on Bitcoin without needing to put the contract's content on the chain. It achieves privacy-protected smart contract functionality on the Bitcoin chain through off-chain interactive communication and presigning methods. Below, we will explain the working principle of DLC through a sports betting example.

Assuming Alice and Bob want to bet on the outcome of the Real Madrid vs. Barcelona match taking place in 3 days, with each of them putting in 1 BTC. If Real Madrid wins, Alice can receive 1.5 BTC, and Bob can only get back 0.5 BTC, which means Alice gains 0.5 BTC and Bob loses 0.5 BTC. If Barcelona wins, Alice can only get back 0.5 BTC, while Bob can take 1.5 BTC. If it's a draw, both of them can get back 1 BTC each.

If we want to make the above betting process trustless, we need to prevent either party from cheating. Using a simple 2/2 or 2/3 multisig is obviously not enough to achieve trustlessness. DLC provides its own solution for this (which relies on a third-party oracle). The entire workflow can be roughly divided into four parts.

Taking the example of Alice and Bob mentioned earlier, first, both parties create a fund transaction off-chain, which locks each other's 1 BTC in a 2/2 multisig address. If this fund transaction is executed, the 2 BTC in the multisig address will require authorization from both parties to be spent.

Of course, this fund transaction is not broadcasted to the chain at first, but is kept locally in the clients of Alice and Bob off-chain. They both know the consequences if this fund transaction is executed. At this point, both parties are only engaging in theoretical deduction and then reaching a series of agreements based on the deduction results.

In the first stage of DLC creation, what can be determined is that both parties will lock their respective 1 BTC in a multisig address in the future.

Secondly, both parties continue to deduce possible events and outcomes in the future: for example, after the match results are announced, there could be various possibilities such as Alice winning and Bob losing, Alice losing and Bob winning, a draw, and so on, leading to different distribution results of the bitcoins in the aforementioned 2/2 multisig address.

Different results require different transaction instructions to be triggered. These "transaction instructions that may be broadcasted to the chain in the future" are called CET, which stands for Contract Execution Transaction. Alice and Bob need to deduce all possible CETs in advance and generate a dataset containing all CETs.

For example, based on the various possible results of the bet between Alice and Bob mentioned earlier, Alice creates the following CETs:

CET1: Alice can receive 1.5 BTC from the multisig address, and Bob can receive 0.5 BTC;

CET2: Alice can receive 0.5 BTC from the multisig address, and Bob can receive 1.5 BTC;

CET3: Both parties can receive 1 BTC each.

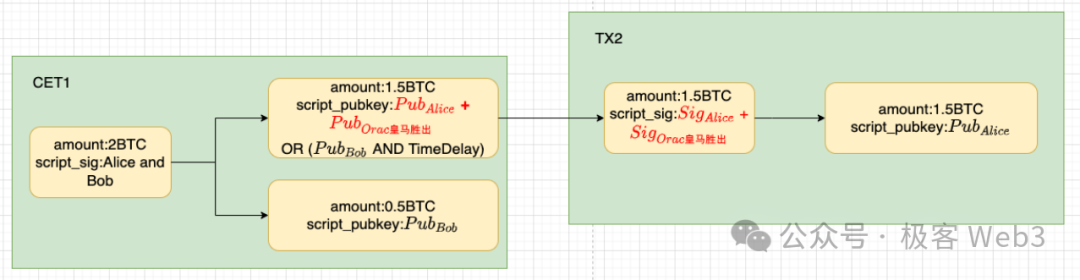

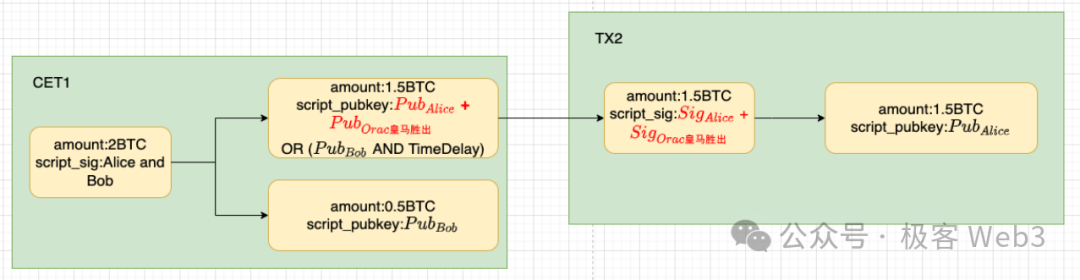

Taking CET1 as an example (Alice gets 1.5 BTC, Bob gets 0.5 BTC):

This transaction means that the 1.5 BTC from the multisig address is transferred to a Taproot address triggered jointly by Alice and the oracle's output result, and the remaining 0.5 BTC is transferred to Bob's address. At this point, the corresponding event is: Real Madrid wins, Alice wins 0.5 BTC, and Bob loses 0.5 BTC.

Of course, to spend this 1.5 BTC, Alice must receive the "Real Madrid wins" result signature from the oracle. In other words, only when the oracle outputs the message "Real Madrid wins," can Alice transfer the 1.5 BTC. As for the content of CET2 and CET3, we can follow a similar process, which will not be elaborated here.

It is important to note that CET is essentially a pending transaction waiting to take effect on the chain. What would happen if Alice broadcasts CET1 in advance or still broadcasts CET1 after "Barcelona wins"?

As mentioned in the previous diagram, when CET1 is broadcasted, the 2 BTC locked in the original multisig address will be transferred, with 0.5 BTC going to Bob, and 1.5 BTC going to a Taproot address. After the oracle outputs "Real Madrid wins," Alice can unlock the BTC locked in the Taproot address. The effect is shown in the following diagram.

At the same time, this Taproot address is subject to a time lock restriction. If Alice cannot successfully withdraw the 1.5 BTC within the time lock period, Bob has the right to take the money directly.

So, as long as the oracle is honest, Alice cannot take the 1.5 BTC, and when the time lock period expires, Bob can take the 1.5 BTC. Adding the 0.5 BTC directly transferred to Bob when CET1 is broadcasted, in the end, all the money will belong to Bob.

For Alice, regardless of whether she ultimately wins or loses, the most advantageous approach is to broadcast the correct CET to the chain. Broadcasting an incorrect CET would result in greater losses for her.

In fact, when constructing the aforementioned CET, improvements have been made to the Taproot's Schnorr signature, which can be understood as using the oracle's public key + event result to construct independent addresses for different results. Later, when the oracle publishes a signature corresponding to a certain result, the BTC locked in the address corresponding to that result can be spent.

Of course, there is an additional possibility. If Alice knows she has lost, she might simply not broadcast the CET1 she constructed. How would this be handled? This is easily resolved because Bob can construct a custom CET for "Alice loses, Bob wins," which achieves the same effect as the CET constructed by Alice, with only minor differences in the specific details, but the result is the same.

The above describes the most crucial process of constructing CET. The third step of DLC involves both Alice and Bob communicating, checking the CET transactions constructed by the other party, adding their own signatures to the CET, and trusting each other. They then each put in 1 BTC and lock it in the 2/2 multisig address mentioned earlier, and then wait for a CET to be broadcasted to the chain, triggering the subsequent process.

Finally, when the oracle publishes the result and provides the signature for the result, either party can broadcast the correct CET to the chain, causing the 2 BTC locked in the multisig address to be redistributed. If the loser broadcasts an incorrect CET first, they will lose all their money. If they broadcast the correct CET, the loser can still get back 0.5 BTC.

Some may ask, how is DLC different from a regular 2/3 multisig? First, under a 2/3 multisig, any two parties conspiring together can steal all the assets. However, with DLC, by pre-constructing a set of CETs, it restricts all possible scenarios between the opposing parties. Even if the oracle participates in a conspiracy, the resulting losses are often limited.

Secondly, in a multisig, all parties need to sign specific transactions to be broadcasted to the chain, while in the context of DLC, the oracle only needs to sign the result of a specific event and does not need to know the content of the CET/pending transactions, or even the existence of Alice and Bob. It only needs to interact with users like a regular oracle.

We can consider that DLC essentially shifts the trust from the multisig participants to the oracle. As long as the oracle does not engage in malicious behavior, the protocol design of DLC can be trusted. In theory, DLC can use a more mature and reliable third-party oracle to prevent malicious behavior. DLC.link and BitLayer utilize this feature of DLC, shifting the trust issue of the bridge to a third-party oracle.

In addition, BitLayer's DLC bridge also supports self-built oracle nodes, adding a layer of fraud proof. When a self-built oracle broadcasts an invalid CET, anyone is allowed to challenge it. The principles of its OP-DLC bridge will be further explained below.

OP-DLC Bridge: DLC Channel + Fraud Proof

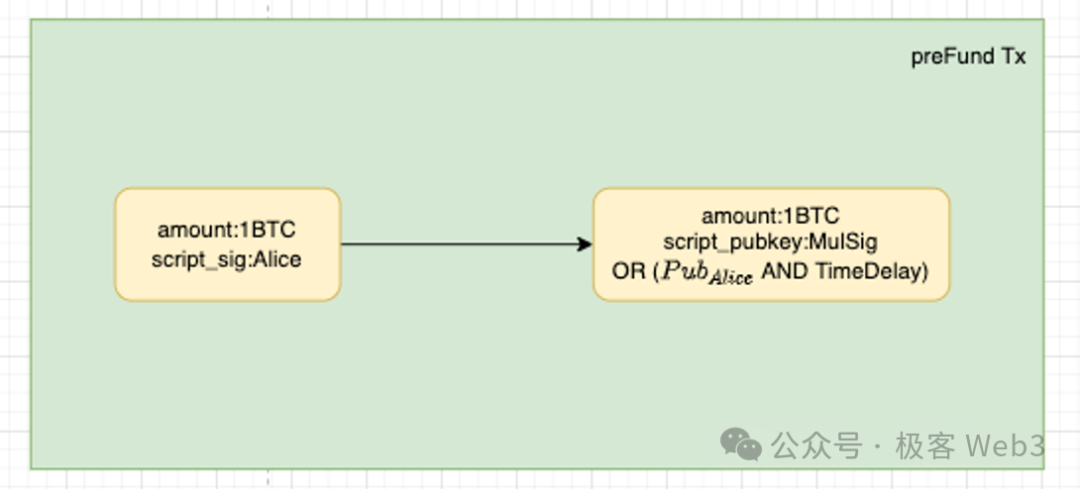

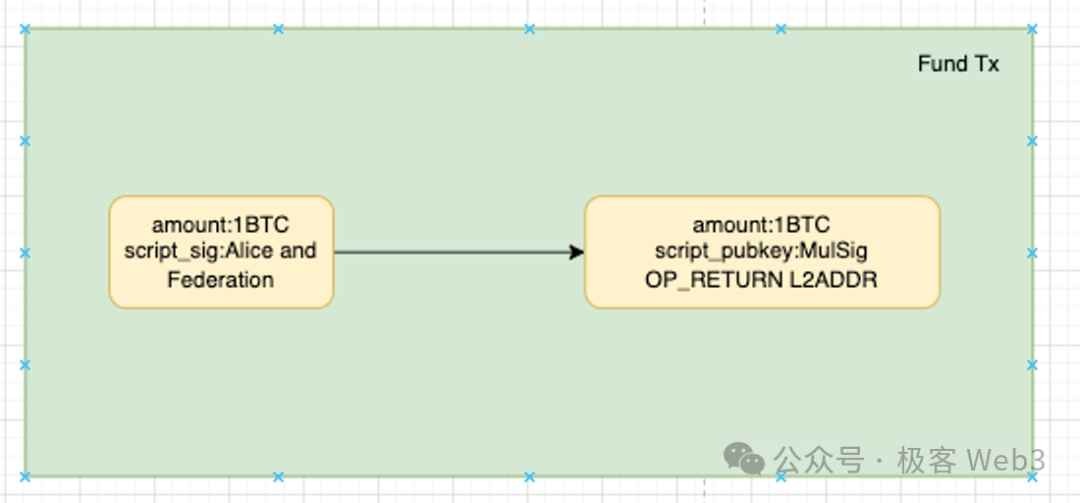

We will explain the operation of the OP-DLC bridge by going through the entire process of deposits and withdrawals. Let's assume that Alice is depositing 1 BTC to L2 through the OP-DLC bridge. According to the two-step transaction mechanism, Alice first generates a pre-fund transaction, as shown in the following diagram:

This actually involves transferring 1 BTC to a Taproot address jointly controlled by Alice and BitVM alliance members, and then initiating a series of processes to create CETs. If the BitVM bridge alliance members refuse to cooperate with Alice's deposit request, Alice can withdraw the money immediately after the time lock expires.

If the BitVM alliance members are willing to cooperate with Alice, both parties can communicate off-chain to first generate the formal Fund deposit transaction (not broadcasted to the chain yet), as well as all the CETs for withdrawal scenarios. After the generation and verification of the CETs, both parties can submit the Fund transaction to the chain.

In the Witness/signature data of the Fund transaction, Alice will specify her receiving address on Layer2. After the Fund transaction is broadcasted to the chain, Alice can submit the above fund transaction data to the bridge contract on Layer2, proving that she has completed the deposit action on the Bitcoin chain and is eligible to have the tokens released to the specified receiving address by the L2 bridge contract.

After the Fund transaction is triggered, the deposit is actually locked in a Taproot multisig address jointly controlled by Alice and the BitVM alliance members. However, it's important to note that this multisig address can only be unlocked by CET, and the BitVM alliance cannot simply transfer the money without cause.

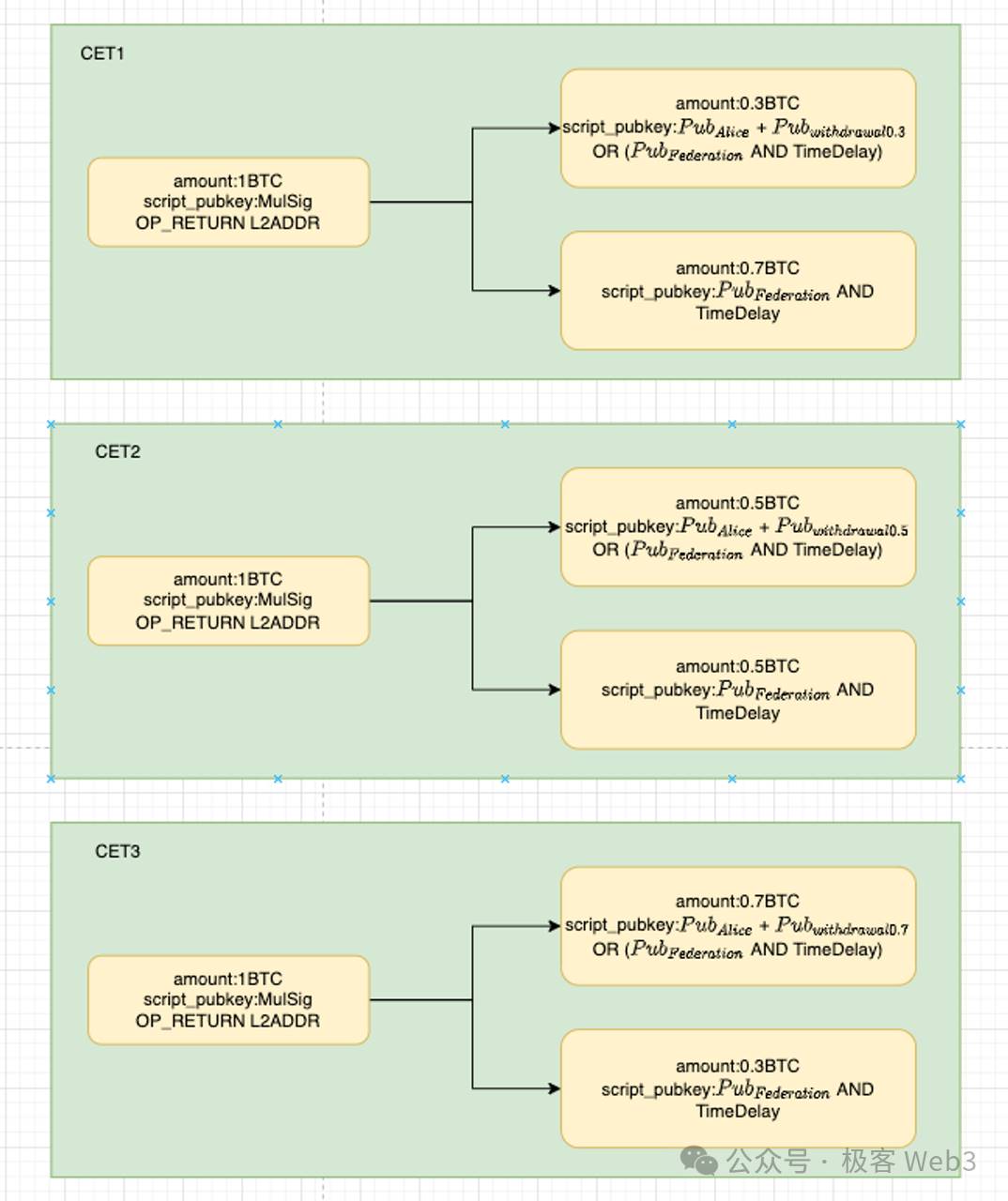

Next, let's analyze the CETs pre-constructed by Alice and the BitVM alliance. These CETs are used to meet potential withdrawal scenarios, such as Alice depositing 1 BTC but only withdrawing 0.3 BTC for the first time, with the remaining 0.7 BTC being allocated to the BitVM alliance's public fund pool. However, any further withdrawals can only be done through the BitVM bridge as mentioned earlier; or simply using the 0.7 BTC to initiate a new pre-fund deposit, as a new asset injected into the DLC bridge, repeating the previously mentioned fund transaction and CET construction process.

The above process is not difficult to understand. It essentially involves having the depositor Alice and the BitVM alliance act as opponents to each other, creating CETs for withdrawal of different amounts, and then having the oracle read Alice's withdrawal declaration on Layer2, determining which CET Alice wants to trigger (how much she wants to withdraw).

The risk here is that the oracle may conspire with the BitVM alliance. For example, Alice declares a withdrawal of 0.5 BTC, but the oracle forges the withdrawal declaration, ultimately causing an incorrect CET to be broadcasted, resulting in "Alice receiving 0.1 BTC, and the BitVM alliance receiving 0.9 BTC."

There are several ways to address this issue. Firstly, a more robust third-party oracle design can be adopted to prevent such conspiracies (making it extremely difficult for the BitVM alliance to conspire with the oracle), or the oracle can be required to stake. The oracle needs to regularly publish Commitments on the Bitcoin chain, declaring that it has honestly processed the withdrawal requests of the depositors. Anyone can challenge the Commitment through BitVM's fraud proof protocol, and if the challenge is successful, the malicious oracle will be slashed.

With the design of the OP-DLC bridge, users can always have a say in their assets, preventing the BitVM alliance from misappropriating the assets. This channel-like design gives users more autonomy and does not require their funds to be mixed with others, resembling a peer-to-peer deposit and withdrawal solution.

Furthermore, considering that the BitVM solution will take some time to materialize, compared to a simple multisig solution, DLC bridges are a more reliable bridging processing model. This solution can also serve as one of the two major deposit and withdrawal gateways used in parallel with the BitVM bridge. If one gateway fails, users can use the other gateway, serving as a good fault-tolerant method.

In summary

BitLayer and Citrea's BitVM bridge solution essentially operates on a "pay first - reimburse later" model, with a dedicated Operator node to pay the withdrawal users, and the Operator can periodically request reimbursement from the public deposit address. If the Operator submits false reimbursement requests, anyone can challenge and slash them.

BitVM2's solution introduces presigning, combining the concept of channels, allowing users to limit the post-deposit processing before the actual deposit, preventing the official cross-chain bridge from misappropriating user deposits.

This bridge theoretically has no security issues but has liveness/availability issues, and cannot meet specific user needs for fund independence and anti-money laundering (essentially still a fund pool model), and has a high difficulty in implementation.

To address this, BitLayer has introduced the OP-DLC bridge solution, which is similar to DLC.link, introducing fraud proof on top of channels and DLC to prevent malicious behavior by the DLC bridge's oracle.

However, due to the high difficulty in implementing BitVM, the DLC bridge will be the first to be implemented and serve as a temporary substitute. As long as the trust risk of the oracle is resolved and a more reliable and mature third-party oracle is integrated, the DLC bridge can become a more secure withdrawal verification solution than a multisig bridge at the current stage.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。