撰文:杨惠萍(西北政法大学)

01 引言

区块链和加密资产的跨境流动性,使各国监管者面临如何在鼓励金融创新与防范系统性风险之间保持平衡的课题。在此背景下,不同法域逐步勾勒出若干不可逾越的「监管红线」,以规制公链资产交易活动并保护投资者权益。例如,反洗钱(AML)与客户身份识别(KYC)要求几乎成为全球共识,各主要司法管辖区普遍将虚拟资产服务商(VASPs)纳入反洗钱法律框架[1]。再如,交易平台对客户资产实行独立托管与隔离,确保客户资产在破产时不致受第三方债权人侵害,也被视为监管底线要求。此外,防范市场操纵、遏制内幕交易,以及避免交易平台与关联方之间的利益冲突,已成为各国监管机构维护市场完整性和投资者信心的共同目标[2][3]。

尽管在上述关键领域出现了监管收敛,但各法域在某些新兴议题上分歧明显。稳定币监管便是典型一例:有的国家将稳定币发行限定于持牌银行等机构并施加严格储备要求,有的则仍在立法探索阶段[4][5]。加密衍生品方面,少数司法管辖区(例如英国)直接禁止面向散户销售此类高风险产品[6];而有的国家则通过许可制度和杠杆限制来规范交易。隐私币(匿名加密货币)的合法地位也存在巨大差异:一些国家明令禁止交易所支持隐私币交易 ,而另一些地区尚未立法禁绝但通过严控合规要求间接打压隐私币流通[7]。另外,在实物资产代币化 (Real-World Assets, RWA) 与去中心化金融 (DeFi) 的监管路径上,各法域态度不一:有的积极建立沙盒试验和专项法规以纳管此类创新,有的则倾向于将其纳入现有证券或金融法规框架加以约束。

为系统分析上述收敛与分歧,本文选取美国、欧盟 / 英国、东亚等具有代表性的法域展开跨法域监管制度比较。第二章至第五章分别聚焦监管红线共识和制度分歧的具体议题,通过引用真实法规条文编号、监管机构发布的官方文件内容,以及典型机构实践或案例,阐明不同法域的监管规定[2][8]。第六章在此基础上总结各法域监管经验的异同,并讨论这种监管版图对全球加密资产市场的制度含义和影响。文章最后的结语部分提出对未来国际监管协调与行业合规发展的思考。

通过上述研究,本文旨在为加密资产机构和合规研究者提供详实的信息参考,助力其理解各法域监管「红线」底限和差异所在,从而在跨境经营中更好地管控合规风险,亦为政策制定者提供比较视角,探索在全球层面推进监管协同的可能路径。

02 监管红线共识之资金合规与资产安全

本章探讨全球监管最为一致的前两条底线:反洗钱(KYC/AML)与客户资产隔离。尽管大方向趋同,但在具体执行路径上仍存在值得注意的细节差异。

2.1 客户身份识别与反洗钱(KYC/AML)的全球基准

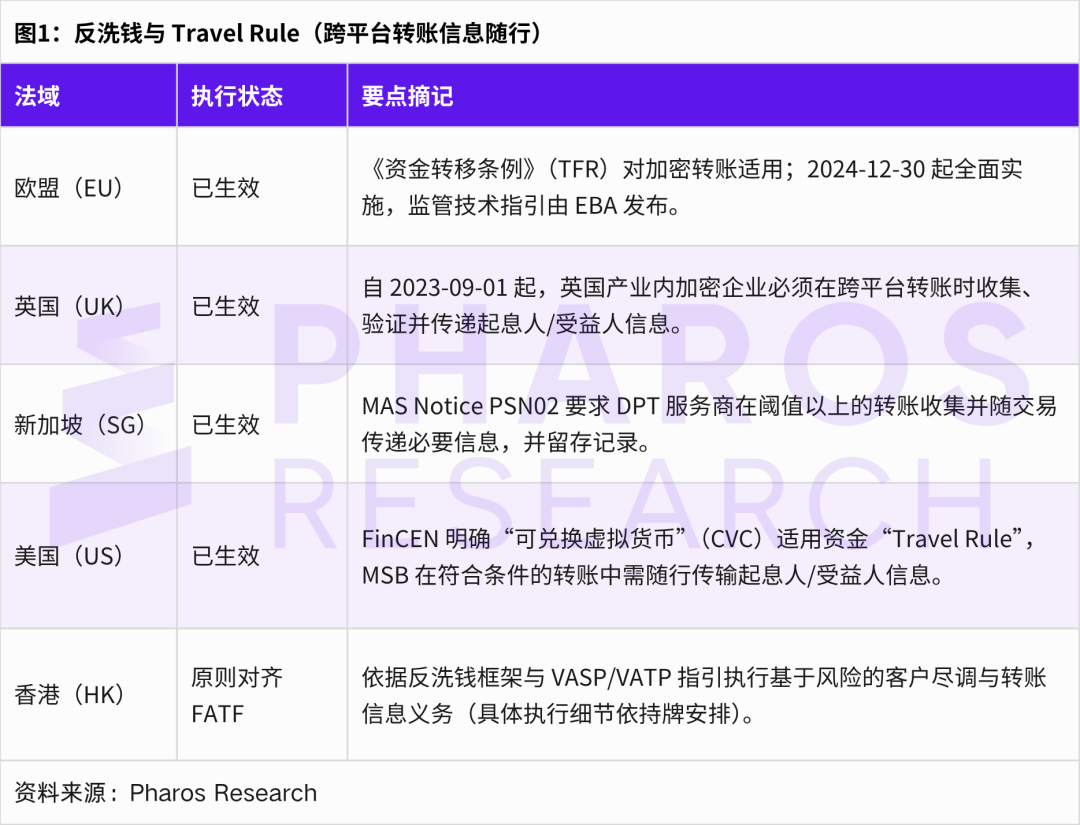

自 2018 年以来,反洗钱(AML)与打击恐怖融资(CFT)要求全面延伸至加密资产领域已经成为全球监管共识。在国际层面,金融行动特别工作组(FATF)于 2019 年修订第 15 号建议,将虚拟资产服务提供商(VASPs)纳入与传统金融机构同等严格的 AML/CFT 义务范围[1]。FATF 并推出「旅行规则」(Travel Rule),要求 VASPs 在大额加密交易时收集并向对方机构传送交易发起人和接受者的身份信息[13]。这一全球标准为各国国内立法树立了基准。时至 2025 年,绝大多数主要司法辖区已将 VASPs 纳入本国反洗钱监管体系,建立起客户身份识别(KYC)、可疑交易报告等制度。据 FATF 最新报告,全球已有 99 个司法管辖区颁布或推进相关法规落实旅行规则,加强虚拟资产跨境交易透明度[14]。

在美国,反洗钱义务主要由《银行保密法》(Bank Secrecy Act, 1970) 及其配套法规确立。财政部下属的金融犯罪执法网络(FinCEN)自 2013 年起明确认定,大多数加密货币交易平台属于「货币服务业务」(MSB)范畴,须在 FinCEN 注册并遵守 BSA 规定[2]。具体要求包括:实施书面的客户身份识别(CIP)程序,收集并核实姓名、地址、身份证号等基本信息;开展客户尽职调查(CDD),识别法人客户的实益所有人并了解客户交易目的[15];保存交易记录并向当局报告可疑活动(SAR)等。此外,美国于 2021 年《基础设施法案》中加入了针对加密交易的税法报告义务,并正考虑立法强化对非托管钱包交易的信息收集。执法层面,美国当局已多次对违反 AML 规定的加密企业提起诉讼和处罚:例如知名衍生品交易所 BitMEX 因未落实 KYC/AML 被认定构成「洗钱平台」,其创始人承认违反 BSA 并支付了 1 亿美元罚款[16][17];另一案例是 Coinbase 前员工因涉嫌内幕交易被控「绕过 KYC 监管牟利」的刑事案件,凸显监管部门对加密行业洗钱和欺诈行为的打击力度。

欧盟自 2018 年通过第 5 号反洗钱指令(5AMLD)起,将虚拟货币交易所和托管钱包服务提供商纳入反洗钱监管范围,要求其登记执照并履行 KYC/AML 义务[18]。各成员国据此修订国内法规(如德国《反洗钱法》、法国《货币金融法典》等),对加密服务商实施身份审查和可疑报告。2023 年欧盟正式通过《加密资产市场监管条例》(Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation, MiCA,法规编号 (EU)2023/1114),确立统一的加密资产服务提供商(CASP)授权制度[19]。MiCA 本身主要聚焦市场规范和投资者保护,但与之并行,欧盟在 2024 年达成了《反洗钱规章》(AMLR)及第 6 号反洗钱指令 (6AMLD) 修订案,对包括 CASP 在内的义务主体提出更高的尽职调查和受益所有人识别要求[20]。此外,欧盟拟成立专门的反洗钱局 (AMLA) 加强跨国监督协调。这意味着在欧盟境内运营的每一家加密交易平台都必须建立严谨的 KYC 程序、持续监控客户交易,并配合执法机关打击洗钱活动,否则将面临牌照吊销和高额罚款等处罚。

亚洲金融中心同样紧随国际标准,建立了针对加密资产的 AML 制度框架。中国香港、新加坡、日本等亚洲法域的监管机构均强调,无论中心化交易所还是其他类型 VASPs,均须建立完备的 AML 合规机制,不得沦为洗钱和非法资金流动的通道。

中国香港于 2022 年修订《打击洗钱及恐怖分子资金筹集条例》(AMLO),自 2023 年 6 月起实施虚拟资产服务提供者(VASP)强制发牌制度[21]。根据该条例及证监会指引,交易平台必须严格执行客户身份识别、风险评估、交易监测和定期审核等措施,并遵守旅行规则要求,将客户和交易信息及时报送给对手方机构[21]。

新加坡通过 2019 年《支付服务法》(PSA) 将数字支付代币服务商纳管,并由金融管理局(MAS)发布《通知》(PSN02)细化 AML/CFT 要求,包括对等值超过 1500 新元的虚拟资产转账适用旅行规则,以及对非托管钱包交易实行加强型尽职调查[22]。

日本则早在 2017 年修改《资金结算法》和《犯收法》(反有组织犯罪收益法),要求加密资产交换业者在金融厅注册并履行 KYC 与反交易洗钱义务[23]。日本规定交易所为客户开立账户时必须验证姓名、住所等信息,监控交易并在超过一定金额(如相当于 10 万日元)的交易时执行额外审查[23]。值得一提的是,日本也是旅行规则的积极推动者之一,已将该要求纳入国内法,对超过 100,000 日元的虚拟资产转账要求传输收发方信息[24]。

通过以上比较可以发现,KYC/AML 监管已成为全球加密资产交易领域的「底线」共识:各法域尽管立法技术和实施力度略有不同,但都承认加强客户身份审查和交易透明度是保障金融体系免受犯罪滥用的首要环节[1]。这一共识的形成,使得跨境加密业务在某种程度上迎来统一的合规门槛——全球性机构必须满足各辖区 KYC 标准并配合可疑资金监控,否则将难以获得营运许可。然而与此同时,不同法域执法力度和具体规则仍存在差异(例如美国针对违规者的刑事追诉、欧盟高度侧重统一规制、亚洲地区偏重牌照管理等),这要求企业在制定全球合规策略时兼顾各地监管细节。

2.2 客户资产独立托管与隔离制度

客户资产隔离(segregation of client assets)是金融监管中保护投资者利益、防范机构破产风险传导的核心制度之一。在传统证券期货领域,各国早有成熟规则(如美国 SEC 的客户资金保护规则、英国 FCA 的《客户资产规则》等)确保经纪商将客户资金与自有资金分开保管。对于加密资产交易平台而言,近年来的一系列事件(包括 2022 年末某全球交易所因挪用客户资金而轰然倒闭)愈发凸显客户资产隔离的重要性。各法域监管者普遍认识到,平台不得将用户托管的数字资产与自身资产混同,更严禁擅自动用客户资产进行借贷、投资,否则一旦平台发生财务危机将严重损害投资者权益。这已成为各主要司法管辖区的监管红线之一。

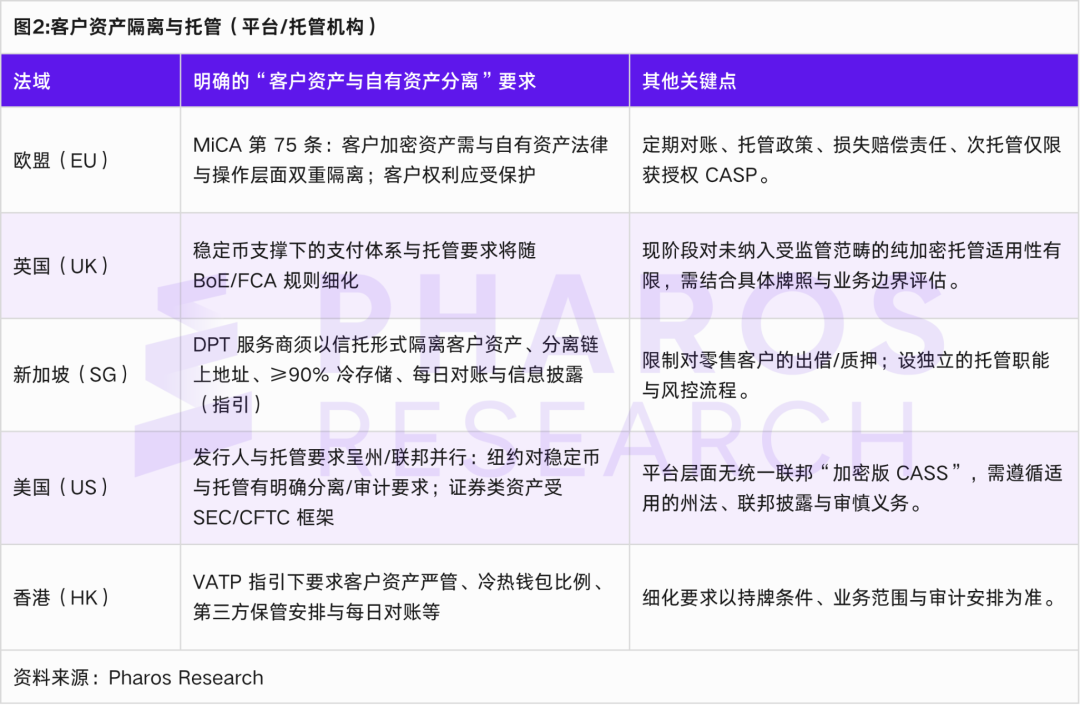

欧盟在《加密资产市场监管条例》(MiCA)中对客户加密资产的托管和隔离提出了明确要求。MiCA 规定,获得授权的加密资产服务商(CASP)在替客户持有加密资产时,必须将客户资产与自身资产进行法律上和运营上的隔离[3]。具体而言,CASP 应在分布式账本上清晰标识客户资产,并确保账上记录将客户持有的代币同公司自有代币区分开来[3]。MiCA 进一步强调,客户资产在法律上独立于 CASP 的财产,即使平台破产清算,其债权人无权对客户托管的加密资产提出索赔[25]。换言之,客户对其托管资产享有所有权或受益权,不因平台破产而转为一般债权。这一规定与欧盟证券领域已有的投资者资产隔离原则一脉相承。在 2023 年 6 月公布的 MiCA 正式文本(Regulation (EU) 2023/1114)第 67 条、第 68 条中,详细列明了 CASP 的托管义务和资产隔离措施,包括在技术和运营层面实现客户资产与自有资产分账管理,以及建立相应内部控制和审计机制以保障隔离有效[26][27]。欧盟此举旨在吸取过往加密平台破产事件教训,消除法律上对客户资产归属的不确定性,为投资者提供类似传统金融中的破产隔离保护。

在美国联邦层面,目前尚无专门针对加密资产托管的统一法律条文,但部分州和监管机构已开始行动。其中,以监管较严著称的纽约州金融服务厅(NYDFS)于 2023 年 1 月发布了针对持有加密资产托管牌照机构(即持有纽约 BitLicense 或信托执照的公司)的指导声明。NYDFS 明确要求,加密资产托管人应「单独核算并隔离客户虚拟货币,与自身持有的虚拟货币分开」。可以采用为每位客户建立独立钱包、内部分类账分户,或将所有客户资产放入与自有资产严格区隔的总账户的方式。但无论采取何种形式,托管机构必须确保不会将客户资产归入自身资产负债表项下,也不得将其用于除安全保管以外的任何目的。NYDFS 同时重申,托管机构不得在未经客户明确指示下挪用、出借或挤占客户资产。此项指导被视为 NYDFS 对近期行业丑闻(如 Celsius 和 FTX 案件)作出的监管回应——这些案件中,法院对客户存放加密资产究竟属于客户财产还是破产财产发生争议,导致客户蒙受损失。NYDFS 的规定从监管上确立了客户资产优先于其他债权受偿的地位。虽然 NYDFS 指引仅适用于与纽约有业务关联的实体,但鉴于纽约在加密监管领域的示范作用,该指引被广泛视为美国实践中客户资产隔离的标杆。其他州如怀俄明等通过《数字资产法》也有类似条款,确认托管的数字资产法律属性为客户所持有的资产,从而提供破产隔离保护。

香港证券及期货事务监察委员会(SFC)在其 2023 年发布的《虚拟资产交易平台营运者指引》中,将「妥善的资产托管」列为持牌平台必须遵循的核心原则之一[5]。根据该指引,平台应采取措施确保客户虚拟资产的安全保管,包括使用高安全等级的冷钱包存储绝大部分客户资产,以及对热钱包设定严格的提款限额和多重签名权限等。此外,指引要求「分开持有客户资产」,即平台需将客户的虚拟资产与自身资产明确区分。实践中,香港持牌平台通常会将客户法定货币资金存放于独立的信托账户,客户加密货币资产保存在专属钱包地址或托管账户,以达到法律和操作上的隔离效果。例如,某些平台声明 98% 的客户资产存放冷钱包且由独立托管人管理,仅 2% 用于满足日常提取需求,并定期向监管报告资产储备情况。这些措施旨在防止平台挪用客户资产自营或作其他用途,并在平台破产、被黑客攻击等极端情形下降低客户损失风险。2023 年年底,SFC 进一步发布通告强调客户资产托管需要强有力的治理和审计,要求高管定期审阅托管安排和私钥管理流程,并引入外部审计核查客户资产存量,提升透明度。这些要求凸显香港监管者对客户资产安全的重视,力图以严谨的制度避免重蹈海外平台爆雷覆辙,维护香港作为合规加密市场的信誉。

新加坡 MAS 在数字支付代币服务商的牌照审批中,同样考察申请人是否具备可靠的托管方案和内部控制,以确保客户资产不被滥用。虽然新加坡暂未颁布专门的客户资产隔离法规,但 MAS 通过指引建议持牌机构将客户代币存放于独立链上地址,与运营资金分离,并建立每日对账与资产证明机制。日本方面,金融厅早在 2018 年就督促加密交换业者执行客户资产「信托化」,即将客户法币存款委托第三方信托机构保管,同时要求至少 95% 的客户加密资产存放于离线环境。2019 年日本修法(《金融商品交易法》修正)更将加密资产纳入金融商品范畴,并正式规定交易业者须每日核对客户资产,确保客户资产数量不低于应有量,一旦低于须立即向监管报告。这实际上建立了客户资产准备金制度,也是一种特殊形式的隔离要求。

综合而言,客户资产隔离已成为各法域监管的共同底线。无论欧美或亚太,监管机构均以明文法规或行政指引的形式,要求加密资产交易平台对客户资产进行独立托管、分账管理,不得将其视为公司财产或挪作他用[25]。这一要求的落实,有助于保护投资者免受平台内部人侵占或债权人瓜分资产的风险,提升市场信心。不过,在跨法域运营时,机构仍需注意不同地区的具体合规细节差别。例如,有的地区要求引入第三方独立托管人,有的允许平台自行保管但要满足资本金或保险要求等。这些差异将在后文相关章节有所讨论。但无论如何,「不挪用客户资产」已是红线中的红线,任何偏离都可能招致严厉的监管惩处甚至刑事责任。

03 监管红线共识之打击市场操纵与利益冲突防控

本章探讨涉及市场公平性的两条底线:反市场操纵与利益冲突防控。

3.1 反市场操纵:市场诚信与操纵防范

加密资产市场的价格波动性和相对缺乏传统市场基础设施,使其容易受到操纵行为侵扰,包括虚假交易(Wash Trading)、拉高出货(Pump and Dump)、内幕交易、蛊惑市场等。如果任由市场操纵泛滥,不仅侵害投资者权益,更可能破坏市场定价功能,削弱公众对加密市场的信任。因此,各主要法域监管机构普遍将打击市场操纵和内幕交易作为监管红线,要求交易平台和相关中介采取措施监测、防范可疑交易活动,必要时向监管部门报告,确保市场公平有序[4]。在法律上,许多国家将严重的市场操纵行为列为刑事犯罪,适用传统金融市场的处罚尺度。

在美国,针对证券和衍生品市场的反操纵法制较为完备。对于被归类为证券的数字代币,适用 1934 年《证券交易法》第 10(b) 条及 SEC 第 10b-5 规则禁止任何操纵市场或证券欺诈行为;内幕交易也在联邦证券法和判例法框架下被禁止和惩处。对于被视为大宗商品的数字资产(如美国监管机构认定的比特币、以太坊),《商品交易法》(CEA) 赋予商品期货交易委员会(CFTC)管辖衍生品市场的操纵,并可对涉及现货市场的欺诈操纵采取执法行动。近年来,美国执法部门积极利用这些法律打击加密市场不法行为:例如,2021 年美国司法部起诉了一起涉及加密货币的内幕交易案,指控某交易所员工利用上币消息先行买入代币获利;SEC 平行提起证券欺诈指控,认为相关代币属于证券。这是首例加密领域「内幕交易」执法,彰显出美国不会因资产形式不同而放松对不公平交易的惩治。同样值得注意的是,CFTC 在 2021 年对一家加密交易平台的高管提起诉讼,指控其默许用户刷量交易,从而制造虚假流动性误导市场,并依据《商品交易法》中的反操纵条款追究责任。虽然美国尚未有专门针对加密现货市场操纵的立法,但监管机构借助既有法律(证券法、商品法和反欺诈条款)已开展多起执法行动。同时,纽约等州检察长办公室也运用《马丁法案》等广泛的反证券欺诈授权,对涉嫌操纵的交易平台展开调查(如 2018 年 NYAG 对多家交易所的交易量造假进行的调查报告)。总体而言,美国强调「法律适用中性」原则,即便是新兴加密资产,只要发生类似传统证券 / 商品的操纵行为,亦可能面临相应法规制裁。

欧盟在传统证券领域通过《欧盟市场滥用规章》(Market Abuse Regulation, MAR)建立了全面的内幕交易和市场操纵禁令。但 MAR 的适用对象主要是受监管市场上的金融工具,不直接涵盖大部分加密资产。为了弥补这一真空,欧盟在 MiCA 中引入了针对加密资产的市场诚信义务。MiCA 第 80 条等规定要求,任何人在专业从事加密交易时,不得利用内幕信息交易相关资产,不得进行操纵行为。同时,MiCA 要求运营交易平台的 CASP 建立市场监测机制,具备识别和处理市场滥用行为的能力[4]。具体措施包括:交易系统需内置监控算法,能够检测异常的大额订单、频繁报撤单等可能的操纵迹象;对价格急剧波动时的平台交易秩序维护,防范有人操纵市场行情;设置涨跌幅度或交易量阈值,自动拒绝超出合理范围的指令;并在发现可疑操纵或内幕交易时及时向主管当局报告。此外,MiCA 要求平台将买卖盘报价及深度信息持续公开,以及交易成交数据及时公开,以提高市场透明度,减少暗箱操作空间。这些规定实质上借鉴了欧盟在证券市场的经验,将许多「同样业务、同样风险、同样规则」的原则应用到加密资产交易中。2025 年,欧盟又在酝酿新的反洗钱规章 (AMLR) 中提及,拟禁止匿名交易和隐私币(见后文),这也是防范市场暗箱操纵的一环(提高可追踪性)。在执法方面,随着 MiCA 生效,各成员国证券监管机构(如法国 AMF、德国 BaFin 等)将有明确授权来查处加密市场的操纵行为。例如,若某人在 Telegram 群组煽动集体买入某代币抬高价格后抛售牟利,可能被认定违反市场操纵禁令而受罚。由此可见,欧盟正逐步将市场滥用监管扩展到加密领域,实现监管的延伸和公平一致。

香港证监会在发放虚拟资产交易平台牌照时,要求持牌平台建立市场监控部门或系统,实时监察异常交易。根据香港 SFC 指引,平台应及时识别并阻止企图操纵市场的交易,例如通过关联账户对倒成交、虚假申报撤单等,并保留日志以备监管查询。如果发现重大可疑操纵行为,平台需向证监会和执法部门报告。虽然目前香港并未将加密资产纳入《证券及期货条例》下的市场操纵罪名(因大多数加密资产不被定义为证券),但持牌平台仍有合规义务确保市场公平。这是一种「以牌照条件落实监管目的」的做法。新加坡方面,MAS 对于在受规管市场(如认可交易所)上市的数字代币,如果其被认定为证券或衍生品,则适用《证券与期货法》(SFA) 的市场操纵和内幕交易条款。但对于未纳入金融工具定义的纯加密资产交易,新加坡目前主要通过行业指南要求交易商自律监测。不过,MAS 已多次发出警示,强调加密市场存在洗钱和操纵风险,提醒投资者警惕。今年(2025 年)新加坡也在考虑修改相关法律,将某些涉及公众利益的代币交易行为纳入《金融市场行为法》调整,如禁止传播虚假或误导性信息影响代币价格等,以弥补执法依据不足的问题。

值得注意的是,为辅助监管和平台履行监控义务,一些专业区块链分析公司和市场监管科技 解决方案开始应用于反操纵。比如某些交易平台使用链上分析工具监测资金在多个账户间轮转,以判断是否存在「多账户合谋操纵」;也有机构开发了 AI 模型,能识别异常价格形态和订单簿行为。监管机构也日益依赖此类技术提升监测效率。例如,美国 SEC 设立了专门的加密资产监察团队,利用大数据分析交易所交易记录,发现异常波动并调查背后是否有人为操纵。欧盟 ESMA 和各国监管者亦在探讨建立跨平台的加密交易报告库,以便识别跨市场操纵行为。

综上,打击市场操纵与内幕交易是各法域共同的监管红线,只是在具体执行方式上因监管范围和法律授权不同而有所差异。从趋势看,随着加密市场与传统金融融合加深,各国将越来越倾向于将加密交易行为纳入现行市场监管框架,实现同等约束。例如,金融稳定理事会(FSB)2023 年提出的建议就强调,各国应确保对加密资产市场实施「有效的监管与监督,以维护市场完整性」,包括配备足够的执法工具遏制操纵和欺诈。这一全球指导原则预计将在各司法辖区转化为更明确的监管要求,使得无论在纽约、伦敦还是新加坡,操纵加密市场都将面临法律追责。对于市场参与者而言,这意味着营造一个更公正透明的交易环境,也是行业长期健康发展的必要条件。

3.2 利益冲突防控:业务隔离与内部治理

利益冲突防控是确保金融机构履行受托责任、维护客户利益的基本要求。在加密资产交易领域,潜在的利益冲突情形包括:交易平台既充当市场运营方又从事自营交易或控制关联做市商,可能利用客户订单信息谋利;平台发行自有代币并将其上架交易,存在价格维护和信息不对称问题;高管或员工掌握敏感市场信息从事个人交易(内幕交易)等。如果不加以规制,这些利益冲突将损害客户利益和市场公平,甚至引发系统性风险(正如某些交易所因关联公司从事高风险交易侵占客户资产而倒闭)。各国监管机构因此将防范和管理利益冲突视为红线之一,要求加密资产服务商建立内部控制和制度安排来识别、减轻并披露潜在冲突。

MiCA 对 CASP 的利益冲突管理提出了明确且强制性的规定。根据 MiCA 第 72 条[28],加密资产服务提供商必须制定和维护有效的政策和程序,以识别、预防、管理并公开潜在的利益冲突。这些冲突可能发生在:(a) 服务商与其股东、董事或员工之间;(b) 不同客户之间;或 (c) 服务商及其关联方开展多种业务功能时。MiCA 要求服务商至少每年评估并更新利益冲突政策,并对冲突情况采取一切适当措施加以解决。同时,服务商须在官网醒目位置披露一般性利益冲突的性质、来源以及其缓解步骤,让客户知情。对于运营交易平台的 CASP,MiCA 更进一步规定,应有特别完善的程序避免自身与客户在交易上的利益冲突,包括在撮合系统上防范与自营单对手成交的情形,以及限制平台人员利用未公开信息交易等。MiCA 也授权监管技术标准细化披露形式等,这显示欧盟将利益冲突视作需要强监管干预的重点领域。MiCA 的背景考虑之一正是吸取过往一些交易所自营及关联交易引发的风险,确保「同场公平」:平台不能一边开赌场一边自己下注而蒙蔽其他赌客。值得一提的是,MiCA 不仅要求服务商自身管理冲突,对于资产参考稳定币发行人等也有类似条款(如要求披露管理储备资产可能产生的利益冲突 ,体现欧盟监管对各类主体统一要求建立利益冲突防火墙。

美国传统金融市场早有应对利益冲突的制度(如交易所与经纪自营分离、银行的防火墙规定等)。针对加密领域,目前没有专门法规强制交易平台进行业务拆分或禁止自营,但监管官员多次表达对「垂直整合」风险的担忧。例如,美国商品期货交易委员会(CFTC)一位委员在 2024 年公开声明中指出,像 FTX 那样交易所与经纪商、做市商、托管等多重角色合一,且缺乏外部监管,酿成巨大利益冲突和风险,监管层应制定规则限制此类纵向整合结构。该声明提到 FTX 崩盘「凸显了利益冲突监管缺位带来的严重危害」。尽管 FTX 当时未在美受全面监管,但其倒闭促使美国立法者和监管者反思:是否需要针对加密交易所制定类似《证券法》中「交易与顾问业务分离」等规定。目前,美国国会一些提案(如 2022 年的《数字商品消费者保护法案》草案)曾考虑禁止加密交易平台开展与客户利益相冲突的某些活动,例如禁止交易所借出客户资产或限制其关联方参与平台交易,但这些法案尚未通过。另一方面,美国监管机构已通过执法倡导利益冲突防控。例如,美国证券交易委员会(SEC)在对 Coinbase 等平台的警示中提及,其允许高管提前出售代币、平台自身投资上架代币项目等行为,可能构成利益冲突且损害投资者,应进行充分的信息披露和管控。又如,美国司法部起诉某些从业者涉嫌使用未公开上币信息交易获利,也属于内部人冲突行为的惩戒。此外,在许可层面,美国纽约州金融服务厅要求 BitLicense 持牌企业提交利益冲突政策,列明董事、高管的个人交易限制以及公司多重业务潜在冲突的缓释措施。这些举措表明美国虽然没有 MiCA 式的一揽子规范,但执法和监管动作正逐步将利益冲突纳入加密平台合规重点。

香港 SFC 在《虚拟资产交易平台指引》中明确要求持牌平台避免利益冲突。具体措施包括:平台不得为自身账户进行任何形式的自营交易(即不做「庄家」);若平台集团内有附属公司从事做市业务,必须向 SFC 报告并确保有严格的资讯隔离墙(Chinese Wall)以防内幕信息泄露;平台高管和员工的个人加密交易也受到约束,需申报和经内部合规审批。此外,平台若打算上线与自身有利益关系的代币(例如平台投资的项目代币或平台发行的原生代币),SFC 要求提供充分披露,并可能视情况不予批准上架,以免平台「左手上市右手割韭菜」。香港这一做法与其证券市场监管惯例一致,如券商自营与经纪分账、避免代理交易与自营冲突等。2023 年 SFC 发牌后,香港首批持牌平台纷纷在公开资料中声明其不从事自营交易、不与客户争利,以博取投资者信任。这在制度上塑造了一道红线:平台只作为中介撮合者,而非市场对手方,从机制上减少利益冲突。

国际组织亦关注此问题。金融稳定理事会(FSB)在 2023 年 7 月发布的加密监管高层建议中明确指出,各司法管辖区应「确保合并多种职能的加密资产服务商受到适当监管监督,包括针对利益冲突和某些职能隔离的要求」[26]。这等于在全球层面呼吁各国对加密交易平台的业务模式进行规范,必要时强制分拆某些冲突职能(例如交易与托管分离、经纪与做市分离等),以免一家机构既当运动员又当裁判。FSB 的立场得到 IOSCO 等机构支持:IOSCO 在 2022 年咨询报告中也建议,监管者应要求加密交易所披露自营交易情况、限制员工不当交易,并可能借鉴传统金融的结构性分业监管经验,以降低利益冲突。可以预见,在 FSB 和 IOSCO 的推动下,「同样的风险、同样的功能、同样的规则」将逐步落实于利益冲突管理领域,统一的国际标准可能在不久将来出现。

总之,利益冲突防控已被纳入各国对加密资产行业监管的基本要求。从欧盟 MiCA 的强制规则到香港、新加坡等地的牌照条件,再到美国监管者的表态和执法,无不传递出明确信号:交易平台等中介机构必须建立健全的内部控制机制,杜绝利用客户不利信息牟取不当利益的行为,一旦发现必须及时披露和制止。这条红线的设立,有助于恢复因若干丑闻而受损的市场信心,促进行业朝更透明、诚信的方向发展。对于运营机构而言,则需要在内部治理上投入更多资源,例如引入独立合规长监督交易、定期进行利益冲突风险评估、培训员工伦理规范等,才能符合各地监管期望并维护自身声誉。

04 监管制度分歧之稳定币监管路径差异

稳定币(Stablecoins)作为锚定法币或其他资产价值的加密代币,在全球范围内迅速发展,引发各国监管机构的高度关注。一方面,稳定币有望提升支付效率和普惠金融,但另一方面,其广泛使用可能冲击金融稳定、货币主权,特别是当稳定币发行缺乏足额储备或透明度时更潜藏崩盘风险(如 2022 年算法稳定币 UST 的坍塌事件)。因此,各国纷纷探索对稳定币的监管路径。然而,由于立法理念和金融体系差异,稳定币监管成为目前跨法域分歧最大的议题之一。主要分歧体现在:发行许可主体、储备金和资本要求、投资者保护措施以及交易使用限制等方面。

4.1 法定货币稳定币的许可与限额

欧盟在 MiCA 中将稳定币区分为两类:一是电子货币代币(EMT),即锚定单一法定货币的稳定币;二是资产参照代币(ART),锚定一篮子资产或非法币价值的稳定币。MiCA 对这两类均实施严格的准入和监管。对于 EMT,发行人必须取得信用机构(银行)或电子货币机构牌照,并在监管机构许可下发行。发行人需持有与发行代币等值的高流动性储备资产(主要为对应法币存款或高质量国债),以确保 1:1 偿付能力。MiCA 还规定,禁止向 EMT 持有人支付利息,以防其与存款竞争。最具特色的是,欧盟为防范欧元区以外的稳定币冲击货币政策,MiCA 引入了交易使用上限:对于非欧元锚定的稳定币(例如锚定美元的 USDT),其每日交易量不得超过 2 亿欧元或不超过 100 万笔交易,否则发行人必须采取措施限制使用(必要时暂停发行或赎回)。这一「2 亿欧元 / 日」以及「100 万笔 / 日」的双重阈值旨在防止某种单一稳定币过度流行、取代欧元进行支付。这是欧盟独有的预防性监管措施,引起业界极大关注(被称为「稳定币交易硬帽」)。此外,MiCA 对被认定为重要稳定币(Significant EMT/ART)的发行人施加更高要求,包括更频密的报告、更严格的流动性管理和储备托管规则等。2024 年起,MiCA 关于稳定币的规定将率先生效,发行人在过渡期后须全面合规,否则不得在欧盟境内提供稳定币相关服务。欧盟此套框架可谓当前全球最全面严苛的稳定币监管,对标的是传统金融中电子货币机构和银行对于支付工具发行的监管标准。

相较欧盟,美国迄今没有联邦层面的稳定币专门法规,这成为重大监管真空。近年来,美国国会曾围绕稳定币发表多份报告和法案草案。2021 年总统金融市场工作组 (PWG) 报告建议,稳定币发行应限制在受监管的存款类机构(如银行),并呼吁国会立法。此后,《稳定币透明度与保护法案》《数字商品稳定币法案》等多项提案诞生,但因政见不一均未通过。结果是在现行法律下,稳定币发行人只能套用现有框架:一些受信托章程监管的公司(如 Paxos、Circle 通过州信托牌照)发行稳定币,接受州金融监管局的监管;其他无牌照的境外公司(如 Tether)发行的 USDT 则游离于美国监管之外,仅因其银行托管账户受美国法规影响而接受部分约束。联邦监管机构只能间接施压,例如美国货币监理署 (OCC) 在 2021 年允许国民银行发行稳定币但附加审慎条件,美联储和 FDIC 警示银行谨慎参与稳定币储备业务等。州级方面,纽约金融服务厅 (NYDFS) 率先对受其监管的稳定币(如 NYDFS 认可的 BUSD、USDP)实施储备和审计要求,2022 年 NYDFS 发布指引要求纽约发行的美元稳定币必须 100% 储备于现金或短期美债,且每日兑付,无利息。怀俄明州则通过创新法律,允许数字资产储备银行(SPDIs)和新设的稳定币机构发行稳定币,但尚无成功案例。

在没有统一规则情况下,美国稳定币市场高度分化:大者如 Tether、Circle 皆自律维持高储备并定期披露资产证明,但漏洞依然存在(如 TerraUSD 算法币在监管真空下做大终至崩盘)。这种监管缺位引发美国立法者警觉,2023 年下半年国会再次尝试推动《稳定币监管法案》,试图建立联邦牌照制度并赋予美联储对非银行稳定币发行的监督权。然而立法进程仍充满不确定。在此背景下,美国当局暂以执法手段管理风险:例如 SEC 对某些涉嫌证券的稳定币(如某社交媒体发行的美元稳定币)发出警告,商品期货交易委员会 (CFTC) 则称主流稳定币为商品资产并保留执法权。整体而言,美国稳定币监管目前处于「法规滞后、各州自行为政、联邦散见指导」的状态,显著不同于欧盟的全面立法模式。

日本在稳定币监管上采取相对保守的路线。2022 年 6 月,日本国会通过对《资金结算法》等法律的修正案,首次明确了稳定币的法律地位和发行资格。新法将稳定币归类为「电子支付手段」,要求只能由受监管的法定机构发行:包括日本的注册银行、受限汇款业者(须具备高资本)或信托公司[6]。这一规定将一般私人企业排除在外,意味着像 Tether 这样的主体无法在日本境内合法发行稳定币。新法还规定,合资格的稳定币必须与日元或其他法币挂钩,可被持有人以面值赎回。同时,禁止发行算法稳定币等非担保形式。对于储备,要求 100% 法币保证金存款于受监管机构。

此外,日本金融厅对于境外稳定币进入日本市场非常谨慎,目前日本交易所基本未上市海外主要稳定币(USDT 等),而由信托公司发行的 JPY 锚定币(如三菱 UFJ 信托计划发行的「Progmat Coin」)正在测试中。2024 年日本又在讨论进一步限制:例如金融厅提出不允许普通银行在公有链上直接发行稳定币(认为风险较高,仅信托银行等可发行),要求对稳定币转账全面应用 KYC/ 旅行规则等。日本模式下,稳定币更像银行存款的替代形式,受银行法及支付条例严格约束,体现了对金融稳定和消费者保护的高度重视。这种模式优点是安全性高,但缺点是抑制了非银行创新动力。目前日本尚未出现大规模稳定币流通,但若各大银行计划发行日元稳定币,则将完全在监管视野内运行,风险相对可控。

香港金管局在 2022 年发布讨论文件,明确提出不允许算法稳定币,并计划重点监管以法币为参考的支付型稳定币。2023 年《稳定币条例》(草案名称)起草完成,并于 2025 年 8 月立法生效[7]。该条例要求凡在香港发行或流通的与法定货币挂钩的稳定币,发行人必须取得香港金融管理局(HKMA)颁发的牌照。牌照申请需满足严格条件:包括在香港设立实体、具备一定法定资本、落实风险管理和技术审核等。条例要求发行人持有 100% 准备金资产(限定为高流动性资产),并在持有人提出时以面值赎回稳定币。同时赋予 HKMA 监督检查权,可审阅储备状况及运营。香港监管的特别之处在于,其不局限银行发行,但确保任何发行人都受到类似银行的审慎监管。这可能为非银行金融科技公司发行稳定币留下一定空间,但监管成本亦不低。香港计划 2024-25 年完成首批牌照审批,强调先行少量发牌、稳步推进。值得注意的是,香港条例将稳定币纳入打击洗钱条例适用范围,要求发行人和经销商落实 KYC/AML 义务。香港此举意味着在亚洲区又一金融中心建立起稳定币监管标杆,有别于新加坡尚未立法而主要通过指导的状态。对市场而言,香港的框架提供了一条合规发行和运营稳定币的路径,有望吸引希望持牌经营的稳定币发行商前来申请。

4.2 非法定资产支撑稳定币(资产锚定代币)的资本与储备要求

除了锚定单一法币的稳定币外,一些稳定币以一篮子法币、商品或加密资产作为支撑(如早期设想的 Libra,即锚定多种储备资产),或以算法加抵押方式维持锚定。这类被称为「资产参考代币」(ART)的稳定币,其价值稳定机制更复杂,风险也更高。各国监管者对于 ART 往往持更谨慎态度。尤其在 Libra 项目(后改名 Diem)于 2019 年引发全球监管反弹后,多数法域明确表示此类跨国篮子币可能威胁金融主权和稳定,应受到严格管制。

欧盟 MiCA 将资产参考代币 (ART) 纳入监管范围,要求发行人取得牌照并遵守与 EMT 相似的一系列要求,包括白皮书披露、储备托管、资本金和流动性计划等。但鉴于 ART 锚定非单一法币,MiCA 对其监管更为严格:首先,ART 发行人必须持有相对更高的最低资本金(至少 35 万欧元或储备 2% 的价值),高于 EMT 发行人要求。同时,ART 发行人须建立清晰的储备资产托管政策,确保储备资产与发行人自有资产完全隔离,并不得挪用。MiCA 规定储备资产可以由合格的托管机构(如受许可的 CASP 托管人或银行)保管,并要求储备高度分散以降低相关性风险。此外,ART 发行人必须设立定期审计机制,每季度披露储备构成和审计报告,以增进透明度。对于重大 ART,MiCA 授权监管机构可施加额外要求,如限制业务规模或要求提供更详细的风险分析。欧盟在 MiCA 中还禁止发行人向 ART 持有人提供任何额外利润激励,意在防止 ART 变相成为投资性产品。综合看,MiCA 对 ART 的要求涵盖治理、风险管理和用户保护多方面,寄望将其风险收敛至可控水平。

美国在 Libra 事件后由多部门联合对其施压,迫使项目修改设计甚至终止。虽然没有出台专门法律,但可以推测,若有类似 Libra 的 ART 问世,美国可能动用《多德 - 弗兰克法》第 I 编(系统重要性支付工具)或证券法对其监管。例如,若 ART 涉及一篮子证券作为储备,SEC 可能认定其为 ETF 基金份额,需要注册;若涉及支付功能且规模巨大,金融稳定监督理事会 (FSOC) 可能将发行人列为系统重要机构受美联储监管。目前美国市场上尚无大规模 ART 运行(主流稳定币多为单币锚定),因此监管分歧主要体现在立场上。美联储官员曾表态,多币种稳定币可能需要央行特别审核。一些美国智库建议,将此类稳定币视为「影子银行货币」,应要求其发行人像货币市场基金一样遵守严格资产组合限制和备付金要求。但由于欠缺实践案例,美国对此未形成固定路径。而在执法方面,如果 ART 引发投资损失,监管机构可能祭出商品或证券法。例如,算法稳定币 Ampleforth 曾被 SEC 调查是否通过 ICO 销售证券,其算法性(锚定与篮子资产或算法公式)未豁免证券法约束。这些都体现美国监管的「原则驱动」:没有专法但会因事制宜套用相关法律。

新加坡在 2022 年曾就稳定币咨询公众,提出为单一货币稳定币设置规则(如主要参考币种须是 G10 货币、最低储备资产质量要求等),但对多资产支撑稳定币则倾向于暂不鼓励。MAS 的思路是先监管好单币种稳定币,再根据国际共识决定是否允许更复杂的结构。香港目前条例主要针对法币锚定币,对于非法币锚定的代币(如算法稳定币、商品支持币)直接不予考虑许可。韩国金融服务委员会 2023 年声明,不允许交易所交易算法稳定币,并对任何带收益或复杂机制的稳定币持否定态度。日本因为只允许锚定法币,自无 ART 空间。综上,在稳定币监管上,欧美差异较大:欧盟已通过 MiCA 建立了一套详尽规范,尤其对国际篮子币明订要求;美国则还在讨论摸索,短期更关注单币稳定币立法。亚洲主要经济体大多谨慎,从紧定位。这种差异意味着,从事稳定币业务的企业在全球扩张时,需应对截然不同的合规要求。在欧盟市场运营,需要取得许可并每日监控交易量不超阈值;在美国市场,虽然没有明确牌照要求,但面临不确定的监管风险和潜在执法;在日本、香港等地区,可能直接面临牌照限制或禁令。因此,监管分歧在此领域表现得尤为明显,也成为未来国际监管协调的一个重点难题。

05 监管制度分歧之市场准入与创新边界

本章讨论另外三个存在显著跨法域监管差异的议题:加密衍生品交易监管、隐私币的合法性,以及实物资产代币化(RWA)与去中心化金融(DeFi)的监管探索。这些领域由于涉及投资者保护、刑事执法、技术匿名性和金融创新边界,各国采取了不同策略,尚未形成统一的国际准则。

5.1 加密衍生品的市场准入与投资者保护

加密衍生品指基于加密资产价格的期货、期权、差价合约 (CFD) 等合约产品。这类产品可用于对冲和投机,放大收益也放大风险。高杠杆、高波动使其对普通投资者极具危险性。传统金融市场对衍生品交易有严格准入(交易所、清算所牌照等),而过去几年大量加密衍生品平台在境外无照运营,吸引全球用户。各国监管机构对此态度不一:有的允许并纳管,有的限制零售参与,有的完全禁止。这成为加密市场监管差异最直观的体现之一。

美国将比特币、以太坊等归类为大宗商品,因此其期货、期权均属于商品衍生品,受《商品交易法》(CEA) 管辖。CFTC 是主要监管者,要求任何向美国人提供加密衍生品交易的设施必须在 CFTC 注册为期货交易所 (DCM) 或掉期执行设施 (SEF),经纪商需注册为期货佣金商 (FCM) 等。同时,平台和中介需遵守客户资产保障和交易报告等规定。迄今,美国已批准少数合规交易所提供加密期货(如芝加哥商品交易所 CME 的比特币期货于 2017 年上线),但这些市场主要面向机构和专业投资者,且交易规模相对有限。绝大部分散户更倾向于访问未注册的平台(如过去的 BitMEX、Binance 等),这违反美国法律。CFTC 过去数年对这类平台展开严厉执法:2021 年,CFTC 和 FinCEN 联手处罚 BitMEX 称其非法向美提供交易并违反 AML 规则;2023 年,CFTC 起诉币安 (Binance) 及其 CEO,指控其多年规避美国法规、默许美国用户交易高杠杆衍生品,并未履行客户身份审查和操纵监控义务。这些行动表明美国将「离岸平台执法」作为保护本国投资者的重要手段。值得一提的是,美国也限制零售参与高度复杂的衍生品:例如 SEC 不允许散户购买加密资产关联的差价合约或某些场外衍生品,CFTC 亦未向零售推广复杂掉期。总体上,美国模式是允许加密衍生品,但交易必须在监管框架内进行,任何企图绕过监管的将被严惩。这种模式与美国对其它金融衍生品一致(「法无许可即违法」)。然而,对于未纳入商品范围的衍生产品(如基于证券型代币的期权),SEC 也可能介入。例如 SEC 曾警告某些平台提供基于未注册证券代币的 swap 合约涉嫌违法。可见,美国将不同监管归口视标的属性而定,但核心是所有衍生品均需牌照,没有监管套利空间。

英国金融行为监管局(FCA)在评估了加密衍生品对消费者的风险后,于 2020 年 10 月宣布禁止向零售客户销售、分销任何参考不受监管加密资产的衍生品和 ETN[8][9]。该禁令自 2021 年 1 月生效,范围涵盖差价合约 (CFD)、期货、期权以及交易所交易票据 (ETN) 等。这一举措在当时属于全球首例:英国监管者认为由于加密资产无法可靠估值、市场操纵频发、波动剧烈且消费者缺乏理解,这类产品不适合散户。禁令预计每年为英国散户避免约 5,300 万英镑损失。禁令实施后,英国零售客户被禁止通过英国公司获取任何加密衍生品敞口。FCA 警告称,任何公司提供此类服务给英国散户都属违法,将被视作骗局处理。然而,到 2025 年 10 月,FCA 出于增强金融中心竞争力的考虑,宣布解除对加密资产 ETN 的零售禁令,但对 CFD 等衍生品仍维持禁售。即英国允许有监管的场所销售一些经过审批的加密 ETN 给散户,但高度杠杆的衍生品仍禁止。这个政策变化体现英国在保护投资者与创新竞争力间寻求平衡。截至目前,英国散户若想交易比特币期货期权,依然无法通过英国本地平台进行,只能经海外渠道。英国对衍生品的强硬立场在主要经济体中较突出,也导致部分活跃交易者转移到欧洲或其他市场。展望未来,英国可能待欧盟 MiCA 效果明朗后,再决定是否调整策略。但短期内,保护散户免受复杂高风险衍生品损失仍是英国监管的优先目标。

在欧盟,MiCA 本身不直接规范衍生品,因为 MiCA 针对的是现货市场和发行领域。加密衍生品若以实物结算且标的非金融工具,理论上可能游离于现行金融指令外。但许多成员国已将加密衍生品视为金融工具的一种。例如,德国 BaFin 认定加密 CFD 和期货属于《第二版金融工具指令》(MiFID II) 下的金融衍生品,需要牌照经营。法国 AMF 也要求任何提供加密衍生合约交易的平台取得相应投资服务提供商资格。ESMA 在 2018 年将加密 CFD 纳入其针对差价合约的产品干预措施,设置了 2:1 的杠杆上限(相比外汇 30:1 更低),以保护投资者。这表明欧盟整体倾向于允许受规管提供,但加强风险管控。个别成员国曾考虑更严措施,如比利时曾短暂禁止分销加密衍生品给散户。欧盟层面目前无如英国般的统一禁令,MiFID 框架和各国监管实践实际上提供了衍生品合规路径。因此,欧盟散户可以通过在塞浦路斯等有牌照券商交易受限杠杆的加密 CFD,或通过欧洲期货交易所 (Eurex) 交易现金结算的比特币 ETN 等。预计随着 MiCA 实施和欧盟金融法规更新,可能会专门针对加密衍生品出台统一规定(ESMA 已在研究这方面)。但就现状而言,欧盟属于谨慎开放态度:监管下可以有,但要防止滥用和过高杠杆,并赋予投资者充分风险警示。

亚洲各国对于加密衍生品的监管呈现截然不同的取态。日本于 2019 年修订《金融商品取引法》,将加密资产衍生品纳入金融商品类别,并对从事加密差价 / 期货交易的业者实施注册监管。日本交易所可为客户提供加密保证金交易,但日本自律规则已将最大杠杆率从 25:1 大幅调降至 2:1。因此,日本用户仍可交易小杠杆的比特币合约,但市场规模受限。韩国则干脆禁止本国交易所提供任何形式的加密期货或期权,认为散户风险过高;韩国投资者如要交易,只能借道海外平台,但韩国政府近年加强监控,要求银行限制对海外加密衍生品平台的汇款。香港在 2023 年推出持牌制度时,明确不允许向散户提供加密衍生品交易,只能提供标的现货交易;专业投资者是否可以通过香港平台参与衍生品也受严格限制。香港仅允许经证监会批准的资产管理公司发行挂钩加密的结构性产品或 ETF 在受监管市场交易(如香港交易所上市的加密资产期货 ETF,面向公众)。新加坡 MAS 对衍生品持谨慎态度,2019 年批准新交所 (SGX) 上市比特币、以太坊掉期合约,但规定零售不能直接参与,仅开放给机构和专业投资者。此外,MAS 在 2022 年强化投资者保护指引中,限制零售获取高风险加密产品,包括衍生品,并要求本地服务商不得通过 ATM 或广告轻易向公众推广任何加密交易服务。总体看,亚洲主流市场多限制零售接触加密衍生品:日本允许但监管严、杠杆低;香港、新加坡、韩国几乎禁止散户参与,只对机构 / 专业开放有限渠道。这与部分西方市场的开放形成对比。

加密衍生品监管分歧带来的直接影响是全球市场流动性的「监管套利」。在严监管或禁令地区(如美国、英国、香港),大量用户仍通过 VPN 和海外账户使用未合规的平台,造成执法难题。相应地,交易量集中在监管薄弱地区的一些大型平台上,这加大了风险集聚。国际监管层意识到这一问题,2023 年金融稳定理事会 (FSB) 发布全球加密监管框架建议时,就强调应加强跨境执法合作,要求各国共同遏制无证加密衍生品活动。另外,IOSCO 于 2023 年发布了关于加密资产交易平台的政策建议,也包含针对衍生品业务的监管标准,如平台应披露杠杆设置、强平机制等。可以预见,未来全球将趋向缩小差异:可能禁止散户高杠杆已成共识,而专业市场则通过许可稳步发展。英国近期解除 ETN 禁令表明,在保护和发展的平衡中,适度开放经过审查的产品可能成为趋势。欧盟也许不会像英国那样禁绝,而是在 MiFID 等体系内加强投资者保护要求,比如强制负余额保护、标准化风险警示等。亚洲部分地区或在适当时机调整,例如香港若验证专业市场安全,未来不排除有限开放零售参与经过审批的衍生品(配套教育)。总之,加密衍生品监管正在从分野走向收敛,以国际监管标准框架为基础,各法域逐步收紧对非法平台的围堵,并在合规渠道内平衡市场需求。

5.2 隐私币的合法地位与监管挑战

隐私币(Privacy Coins)指通过技术手段(如环签名、零知识证明等)实现交易匿名和地址隐匿的加密货币,代表有门罗币 (XMR)、大零币 (ZEC)、达世币 (DASH) 等。其支持者认为隐私币保障金融隐私权,但监管者则担忧它们被广泛用于洗钱、逃避制裁等非法活动,因为传统链上分析对其交易流向几乎失效。围绕隐私币,各国监管政策分化明显:有的明令禁止,有的严格限制流通,有的尚未采取直接行动但通过 AML 规则间接打击。

日本是最早禁止隐私币交易的国家之一。2018 年,受 Coincheck 交易所被黑事件(黑客利用匿名币清洗资产)等影响,日本金融厅 (FSA) 要求国内注册交易所下架所有具高度匿名特征的币种,包括门罗币、达世币等。这一要求通过自律组织(日本加密资产交易协会 JVCEA)的规定落实,新申请的交易所牌照也不得上市匿名币。FSA 官员明确表示,匿名币违反了日本反洗钱制度的「可追踪」原则,不应在合规市场存在。同样地,韩国在 2021 年 3 月《特定金融信息法》修订后,金融服务委员会 (FSC) 发布指南禁止虚拟资产服务提供商处理「无法识别交易记录的匿名数字资产」,各韩国交易所遂相继下架隐私币[10]。韩国还禁止通过混币服务来隐藏交易来源。迪拜等中东地区也跟进:阿联酋迪拜 2023 年虚拟资产法规中规定禁止发行或交易增强匿名功能的加密货币。这些法域采取的策略是直接取缔,认为此类资产弊大于利,不应允许。

欧盟目前尚未完全禁止隐私币,但正朝该方向迈进。欧盟议会和理事会就《反洗钱规章 (AMLR)》达成的政治协议(2023 年),提出自 2027 年起,禁止加密服务提供商与匿名钱包或匿名币交易往来[12]。根据 2025 年 5 月 9 日公布的信息,欧盟将要求从 2027 年 7 月起,虚拟资产服务商不得提供涉及匿名币的交易服务,且须对私人托管钱包交易超过 €1000 执行严格身份核验。亦即,届时在欧盟经营的交易所将不能上市门罗、ZEC 等隐私币。此外,欧盟已有成员国采取临时措施:如比利时金融监管当局 2022 年要求当地交易商报告任何涉及匿名币的交易并建议停止支持。法国 AMF 在许可严格管制,尚无隐私币被批准。欧洲执法机构 Europol 也频繁示警隐私币对追踪犯罪资金之阻碍。欧盟此举遭到加密行业一些人士批评,认为此举损害个人隐私权。然而,从监管角度看,匿名币的存在确实令 AML/CFT 框架难以执行,FATF 也在多个报告中点名匿名增强技术的风险。可以预期,欧盟在实施禁令前这几年,会通过软性措施逐步压降隐私币使用,如将其纳入高风险交易类别,要求提高尽职调查程度等,为 2027 年正式禁令做好铺垫。一旦禁令生效,欧盟将成为继美日韩之后又一主要司法区排斥隐私币。

美国目前没有法律禁止持有或交易隐私币,主要的合规交易所(Coinbase 等)基于自身风控政策也大多不支持这些币。然而,美国监管机构通过其他手段打击隐私交易,比如 2022 年美国财政部海外资产控制办公室 (OFAC) 直接制裁了加密货币混币服务 Tornado Cash,这是针对匿名化工具的重大举措。尽管 Tornado Cash 不是代币,但这一行动释放出强烈信号:美国不容忍完全匿名的加密交易渠道。不少行业观察者据此推测,若隐私币广泛用于非法活动,美国也可能考虑类似手段,比如将特定隐私币地址列入制裁名单等。另外,美国司法部和国税局多年来投资于隐私币的链上分析工具研发,希望提升破案能力。交易所方面,2019 年美国交易所 Kraken、ShapeShift 等主动或被迫下架了门罗、达世币,以免监管麻烦。美国态度可概括为「技术中立但风险导向」:不直接立法禁之,但如发现滥用就严查。新加坡亦无明文禁令,MAS 主要通过 AML 指引要求 VASPs 对匿名交易采取高强度审查,不符合审查的交易不得进行。这实际上使得新加坡持牌机构也无法方便地支持隐私币。2020 年,大型交易所币安(当时在新加坡运营)就停止了门罗等币的交易。其他如澳大利亚正考虑紧随欧盟脚步,有消息称澳政府有意禁止匿名币兑换法币活动。总的来说,在未明确立法的法域,市场力量已部分自行调整:主流合规平台普遍回避隐私币,以满足银行和监管的合规期望。

隐私币监管的分歧反映出隐私权 vs. 合规的冲突。一方面,金融隐私是个人权利,过度金融监控可能有侵犯嫌疑;另一方面,完全匿名使执法陷入黑暗。少数国家(如瑞士)在讨论是否能通过强制链上可审计性等方法折中,比如要求隐私币设「观测钥匙」供有权限者查看,但技术上尚无成熟方案。因此目前看,各国倾向牺牲隐私币的存在以换取 AML 合规完整性。FATF 在对各国评估中也将匿名技术视为高风险因素,导致多数合规机构不愿触碰隐私币。在这种环境下,隐私币的生存空间越来越小,用户群也转入地下或限于高技术极客圈。跨境影响也值得注意:由于日本、欧盟等禁止,隐私币交易更多流向无监管的市场,形成监管真空的风险传递。国际合作可望减少此漏洞,例如各国联合共享可疑地址情报,加强对法币出入口的监控。总体预测是,隐私币将在更多法域受到限制甚至禁用,直至出现足以平衡隐私与监管的新技术方案。这一领域的监管分歧实际上在逐渐缩小,因为曾经观望的欧美国家正追随东亚国家的严格态度。而对投资者和行业而言,这意味着隐私币将难以融入主流金融,相关业务须慎重考虑地域合规风险。

5.3 实物资产代币化(RWA)与去中心化金融 (DeFi) 的监管探索

实物资产代币化 (RWA) 指将现实世界的资产(如债券、股票、不动产、商品等)以区块链代币形式表示和交易的过程。去中心化金融 (DeFi) 则是一系列无需中介、通过智能合约提供金融服务(如借贷、交易、衍生品等)的应用生态。RWA 和 DeFi 被视为区块链金融创新的前沿,可能带来交易效率提升和金融包容性,但也给传统监管框架带来巨大挑战。如何将这些去中心化或跨界的新模式纳入监管,是各国目前分歧最大且仍在探索的议题。

美国对 RWA 和 DeFi 采取以现有监管框架执法为主的策略。对于 RWA,只要代币代表传统金融资产(如股票、债券),SEC 一概视其为证券,要求符合法规发行和交易。例如在 2018-2020 年间,美国出现一些试图代币化股票的平台(如 DX.Exchange、Uniswap 上的股票代币),SEC 迅速出手叫停,认为其违反证券法。即使代币化资产是实物(如黄金、不动产权益),若公众投资且期待收益,也可能被 SEC 纳入证券范畴。同样,CFTC 则关注代币化商品衍生品,已对一些 DeFi 协议提供的商品掉期交易提起诉讼。典型案例如 2022 年 CFTC 起诉 Ooki DAO,这是首例针对 DeFi DAO 的执法,指控其无牌经营杠杆交易平台,最终通过缺席判决处罚 DAO 资产。美国财政部亦在 2023 年发布《DeFi 非法金融风险评估报告》,指出许多 DeFi 服务未遵守 BSA 义务,未来将加强监管和立法推动。另一方面,美国也有鼓励创新声音,如怀俄明州立法承认 DAO 合法身份、国会一些议员倡议建立「沙盒」给予合规试验空间。但整体联邦层面尚未出现专门针对 DeFi 的法规,大多数活动落入灰色地带,由监管机构以现行法律来「硬套」。这导致美国 DeFi 从业者面临极大合规不确定性,不少项目选择迁往海外。尽管如此,美国仍通过长臂管辖打击其认为非法的 DeFi 活动,如对海外混币服务、去中心化交易所的人员进行制裁或指控。可以说,美国目前在 RWA/DeFi 监管上呈强执法 - 弱立法态势。

欧盟 MiCA 未直接涵盖 DeFi 协议和完全去中心化的发行活动(如无主体的 DAO),这是立法时刻意的留白。欧盟官员表示,将在 MiCA 实施后再评估如何监管 DeFi。2023 年,欧盟委员会发布了对 DeFi 的研究报告,倾向于技术驱动的监管:通过监控区块链数据(所谓「嵌入式监管」)来实现对 DeFi 活动的监督,而非完全沿用传统中介监管模型。这种思路源自 BIS 及法国等专家建议,让监管节点嵌入到 DeFi 网络中自动收集所需数据。立法上,欧盟或将借即将成立的欧洲反洗钱局 (AMLA) 对 DeFi 实施一定的 AML 要求,例如若智能合约有可识别开发者 / 控制人,则将其视为 VASPs 须登记。这在欧盟《第 6 号反洗钱指令》草案中已有端倪。关于 RWA,欧盟已经推 DLT 试点监管框架 (Regulation (EU) 2022/858),允许受监管机构在受控沙盒环境下发行和交易证券型代币。该试点自 2023 年 3 月起实施,为期 6 年,已有多家交易所和央行参与,用于测试债券、基金份额的链上发行和交易。目标是为未来修改金融法打下基础。这表明欧盟对 RWA 持较开放和积极的态度,希望占领先机。但对于去中心化程度高的 DeFi,欧盟仍抱谨慎,等待更清晰国际方案。近期欧盟在 G20 场合支持 FSB 对加密和 DeFi 的框架性原则,但国内尚未有硬性规定。可总结为:欧盟拥抱 RWA 创新(在监管下),暂时观望纯 DeFi。

新加坡 MAS 相对前瞻,早在 2022 年便推出 Project Guardian,联合金融机构探索 DeFi 在批发金融市场的应用,包括代币化债券及银行间借贷等。2023 年,新加坡星展银行等成功通过 DeFi 协议完成了国债代币化交易试验。这些在 Sandbox 中进行的项目,受 MAS 观察,以评估监管需求。新加坡还设立了金融科技监管沙盒,少数 DeFi 初创可以申请在有限范围免除部分规则测试业务。然而在普遍规则上,MAS 仍强调 DeFi 应用如涉及受监管活动,则相关参与者必须持牌。如 DEX 运营者若有中央参与,则视为市场设施,需要遵守 SFA 许可;DeFi 借贷若涉及证券借贷亦受规管。香港在 2023 年也展现出对 DeFi 日益兴趣:金管局的 e-HKD 实验探讨 DeFi 支付,证监会官员在公开场合表示会研究 DeFi 治理机制。如果说香港在零售加密上谨慎,那么对机构级 RWA 项目及合规 DeFi 可能持开放态度,尤其期望巩固国际金融中心地位的一部分。在内地,中国人民银行等机构 2021 年明确表态禁止任何境内加密交易和 DeFi 活动,但近年也通过 BSN 项目支持「开放许可链」,探索联盟链环境下的资产数字化,属于另辟路径。

鉴于 DeFi 和 RWA 跨境属性强,全球标准制定机构亦开始行动。金融稳定理事会 (FSB) 2023 年 2 月发布报告,指出 DeFi 目前和传统金融高度关联,许多所谓 DeFi 其实有集中节点,应纳入监管。报告建议加强对稳定币和加密集中平台的监管,从外围削减 DeFi 风险。国际证监会组织 (IOSCO) 在 2023 年其加密建议中也覆盖了一些 DeFi 场景,强调应「同功能同规」,例如若某 DeFi 提供类似证券交易功能,则应该有实体对其负责监管。可以预见未来几年,国际层面将逐步提出 DeFi 监管原则,如要求设置合规代理人负责 KYC/ 审计,或鼓励代码自带监管访问等。

RWA/DeFi 监管目前是探索阶段,多元实践并存。美国强化执法维护现行法规权威,欧盟采取试验和新思路并举,亚洲部分地区主动创新但小心控制范围。这一领域的监管分歧源于各方对创新和风险的不同权衡,但随着技术成熟和事件反馈,可能逐步形成一定共识。例如,对 RWA 的主流态度是欢迎创新但确保托管和投资者权利(如通过沙盒磨合法律),对 DeFi 的共识苗头是凡是「假去中心化」实为有主体的,都应依法监管;真分散无主体的,则应研究新机制。监管工具可能创新,如代码监管、DAO 登记等。但在实现之前,跨境监管难题仍突出,尤其 DeFi 无国界,这需要各国监管机构加强信息共享和联合行动。目前已有实例:2023 年美韩荷兰三国合作打掉了一个利用 DeFi 协议洗钱的朝鲜黑客集团资产。这种执法合作或许预示着未来对不受控 DeFi 行为的围堵将超越单一法域界限。对于市场参与者而言,在 RWA 领域,选择适当司法管辖并取得所需牌照将是关键;在 DeFi 领域,若要走合规路线,需密切关注法规动态,可能要为 DAO 找法律代理或为智能合约嵌入合规接口等,以适应未来监管方向。

06 监管收敛的意义与分歧的制度含义

通过上述对比分析,可以看到全球加密资产交易监管出现了「共识趋同」与「制度分野」并存的格局:

一方面,各主要法域在基本风险防控原则上高度一致,逐步形成了一套事实上的监管底线(红线)共识——反洗钱 /KYC、客户资产隔离、反市场操纵、利益冲突防控等四大领域成为监管标配。这些共识的形成,有赖于国际标准组织(如 FATF、FSB、IOSCO)近年来针对加密资产的框架性指导,也反映出各国监管者在吸取多起市场乱象和风险事件教训后的理性选择。例如:FATF 标准推动下全球 AML 法规同步升级,使「匿名无识别」的加密交易模式难以立足[1];大型交易所倒闭案例促使各国竞相完善客户资产保护规则(欧盟 MiCA、纽约指引、香港 SFC 指引皆有体现)[25];市场操纵和内幕交易行为引发的执法行动在不同法域此起彼伏,从而强化了行业对于市场诚信的重要认知[4];利益冲突带来的灾难性后果(如 FTX 事件)更是在全球范围敲响警钟,各国纷纷填补监管空白,加强功能隔离和内控要求[5]。这些收敛反映出,加密资产越发融入主流金融监管范畴:各国正尝试将传统证券、期货、银行监管的成熟经验移植到加密领域,确保「同样业务、同样风险、同样监管」。这种收敛对于跨国经营的加密机构是利好,因为逐渐统一的监管标准有助于减少合规不确定性和降低在多地运营的制度摩擦。当 KYC、AML、反欺诈等成为普世要求时,合规经营者可以按一套高标准来设计全球业务流程,而不必面对截然相反的要求。同时,监管共识的形成也意味着市场进入门槛提高:不符合这些底线的业务模式(如匿名交易所、无托管隔离的平台)将难以存续,从而净化市场环境,保护投资者免受极端风险。

另一方面,在具体制度和新兴议题上,各法域现阶段仍存在明显分歧。稳定币、衍生品、隐私币、RWA/DeFi 四大领域的监管分野,体现了各国在法律传统、风险承受度和政策优先目标上的差异:欧盟采取立法先行的严管模式(MiCA 对稳定币和 CASP 全覆盖,并未雨绸缪限制稳定币规模),美国则立法滞后更多依赖监管和司法实践(联邦稳定币法久未通过,靠州监管和执法权宜维持);英国干预主义色彩浓烈(如率先禁止散户衍生品[8]),而欧陆相对平衡考虑(限制杠杆但未完全封杀);亚洲一些国家态度更保守(日本韩国直接禁隐私币、香港严控散户交易),而另一些则勇于试验(新加坡沙盒 DeFi、瑞士探索数字证券等)。这些分歧短期内难以完全弥合,因为它们涉及各国对金融创新与稳定的不同立场。特别是 DeFi 等课题,不确定性极高,各法域观望与尝试并存,料将持续一段时间的探索。

对于加密资产机构来说,监管分歧既意味着套利空间,也意味着风险集中。过去,不少机构利用不同法域规则差,选择宽松地区设立,向限制地区用户提供服务,实现业务扩张。然而,随着共识红线的建立和跨境协作加强,这种套利空间正受到挤压。例如,未取得美国许可的平台即便身处海外也难逃法律追究(BitMEX、币安案);隐私币即使在某些国家合法,但一旦主要经济体封禁,其全球流动性和价值也会大幅受限。不仅如此,「监管短板效应」开始显现:风险活动容易向监管洼地集中,反而引来更严厉打击和尾部风险。正如 FSB 所警告的,如果某国法规宽松导致其成为违规业务避风港,长远看本国投资者和声誉都会受损,国际合作压力也会增加。因此,合规经营者逐渐认识到,与其钻空子不如主动提高标准,提前适应未来更统一严格的监管环境。这也是近期许多大型交易所主动申请多国牌照、完善透明度的动因。

从制度含义看,监管收敛部分体现出传统金融监管逻辑在新领域的有效性:例如,银行业沿用多年的 KYC/AML 机制,仍然是治理加密非法资金的有效手段[1];证券市场养成的市场操纵监测技术,同样适用于发现异常的加密交易[4]。这说明金融活动尽管形式变化,其风险本质有相通之处,监管经验可以跨界迁移。这为监管机构应对金融创新增强了信心,也指明了方向:未来制度完善应着眼于功能监管,以活动和风险为基础,而非法律形式。FSB、IOSCO 等的原则都在强调技术中立和功能导向。另一方面,监管分歧部分反映出现有法律框架的局限:当创新超出既有概念,如完全去中心化的协议、全球通用的稳定币,传统基于中心中介的监管模式便面临抓手缺失,各国才会各谋对策,甚至干脆禁止。这暴露出现行国际金融监管体系在应对无国界、无主体的金融现象时的困难。由此带来的制度启示是:未来可能需要全新的国际规制工具。例如,针对全球稳定币,G20 已支持 FSB 提出的统一监管框架,要求发行人在主所在国和参考货币国都需许可;针对 DeFi,探索跨境监管沙盒或技术嵌入式审计,让代码承担部分监管职能。这些都是各国主管机关接下来需要合作攻坚的方向。

最后,从国际协调角度,逐渐收敛的监管红线为推进跨境互认与协作奠定基础。例如,反洗钱方面已有 FATF 标准,各国可依据等效原则互认对方的 VASPs 监管,高风险交易情报交换更加顺畅;客户资产保护若有共通原则,则跨境托管和破产处置可参照合作(目前欧盟就考虑与他国签协议确保客户资产跨境返还);打击市场操纵则需要交易数据共享、执法协助,FSB 已倡议建立全球加密风险监测机制。这些合作都有赖于各国规则相近乃至统一,否则难有共识。可见,在红线共识基础上深化国际协同将是趋势。相应地,对于跨国机构而言,未来合规运营的模式可能出现:在多个主要司法区获取牌照,遵守类似的高标准规则,在监管范围内开展业务,并利用各地监管互认降低重复成本。监管的趋同让这样的模式成为可能,也使得合规机构相较不合规者拥有更公平的竞争环境。

总而言之,当下全球加密资产交易监管呈现「基础规则趋同、前沿问题各探」的状态。这既是传统监管体系对新金融事物的主动延伸,也是各法域根据自身国情进行制度创新的表现。对于行业和监管者来说,都需要在这收敛与分歧并存的环境中保持敏锐:一方面坚守底线,共筑安全规范的市场秩序,另一方面包容合理试验,为新的国际制度安排积累经验。只有这样,才能既防范风险又不扼杀创新,使公链资产交易真正融入可持续的金融发展轨道。

07 结语

公链资产交易作为 21 世纪金融创新的前沿,在短短十余年间经历了野蛮生长与强力规制的交织。在全球范围内,各国监管从最初的莫衷一是,到如今逐步勾勒出共同的红线与规范,也是在探索中不断试错、纠偏的结果。监管的收敛为市场确立了秩序和信心,但监管的分歧亦提醒我们:法律与创新的博弈从未停歇,制度演进永无止境。对于投机型加密资产机构而言,理解并尊重各法域监管红线,是合规经营的基本前提;审慎研判制度分歧下的机遇与风险,则是全球战略布局的必修课。本文通过跨法域比较,为读者梳理了当前监管版图的全景,也为未来政策和学术讨论提供了素材和启示。展望未来,随着国际合作深化和技术手段进步,我们或将看到更多监管差异的弥合与新规则的诞生。监管者与从业者唯有持续对话、相向而行,方能在保障金融安全与推动创新发展之间取得更加成熟的平衡。监管红线的收敛与分歧,是当下的写照,更是走向未来的起点。我们期待一个既秩序井然又充满活力的全球加密资产市场在各方努力下得以实现。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。