1. The Institutional Ceiling of Complete Anonymous Privacy: Advantages and Dilemmas of the Monero Model

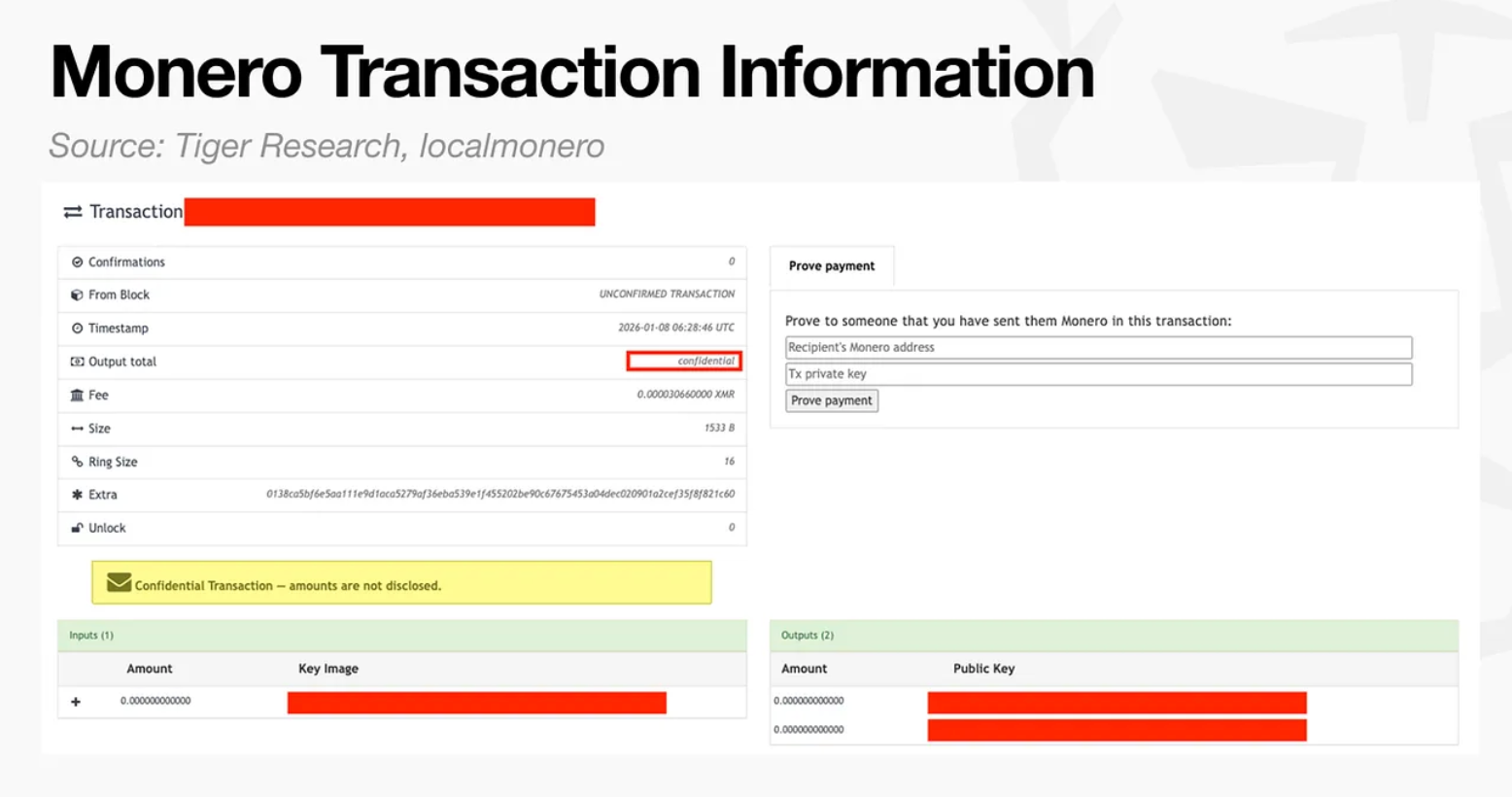

The complete anonymous privacy model represented by Monero constitutes the earliest and most "pure" technical route in the privacy race. Its core goal is not to balance transparency and privacy, but to minimize on-chain observable information, cutting off third parties' ability to extract transaction semantics from public ledgers as much as possible. To achieve this goal, Monero employs mechanisms such as ring signatures, stealth addresses, and RingCT to obscure the three key elements: sender, receiver, and amount. External observers can confirm that "a transaction has occurred," but it is difficult to deterministically reconstruct the transaction path, counterparties, and value. For individual users, this experience of "default privacy, unconditional privacy" is highly attractive—it transforms privacy from an optional feature into a systemic norm, significantly reducing the risk of "financial behavior being tracked long-term by data analysis tools," and providing users with near-cash anonymity and untraceability in payments, transfers, and asset holdings.

On a technical level, the value of complete anonymous privacy lies not only in "hiding" but also in its systematic design to counter on-chain analysis. The greatest externality of transparent chains is "composable surveillance": the public information of a single transaction can be continuously pieced together, gradually linking it to real identities through address clustering, behavioral pattern recognition, and off-chain data cross-validation, ultimately forming a "financial profile" that can be priced and abused. The significance of Monero is that it raises the cost of this path to a level that can change behavior—when large-scale, low-cost attribution analysis is no longer reliable, the deterrent effect of surveillance and the feasibility of fraud both decline. In other words, Monero does not only serve "bad actors"; it also responds to a more fundamental reality: in a digital environment, privacy itself is part of security. However, the fundamental issue with complete anonymous privacy is that its anonymity is irrevocable and unconditional. For financial institutions, transaction information is not only essential for internal risk control and auditing but also serves as a legal obligation under regulatory requirements. Institutions need to retain traceable, explainable, and submitable evidence chains within the frameworks of KYC/AML, sanctions compliance, counterparty risk management, anti-fraud, taxation, and accounting audits. Complete anonymous systems "permanently lock" this information at the protocol level, leading to a structural inability to comply even if institutions subjectively wish to do so: when regulators require explanations of the source of funds, proof of counterparty identity, and provision of transaction amounts and purposes, institutions cannot restore key information from the chain, nor can they provide verifiable disclosures to third parties. This is not a case of "regulators not understanding technology," but rather a direct conflict between institutional goals and technical design—the bottom line of the modern financial system is "auditable when necessary," while the bottom line of complete anonymous privacy is "not auditable under any circumstances."

The external manifestation of this conflict is the systematic exclusion of strong anonymous assets by mainstream financial infrastructure: exchanges delisting them, payment and custody institutions not supporting them, and compliant funds being unable to enter the market. It is worth noting that this does not mean that real demand has disappeared. On the contrary, demand often migrates to more concealed and higher-friction channels, creating a "compliance vacuum" and the prosperity of "gray intermediaries." In the case of Monero, instant exchange services have at times accommodated a large amount of purchasing and exchanging demand, with users paying higher spreads and fees for availability, while also bearing the costs of fund freezes, counterparty risks, and information opacity. More critically, the business models of such intermediaries may introduce ongoing structural selling pressure: when service providers quickly convert the Monero fees they collect into stablecoins and cash out, the market experiences passive selling that is unrelated to real buying, thus suppressing price discovery over the long term. Thus, a paradox emerges: the more compliance channels exclude them, the more demand may concentrate on high-friction intermediaries; the stronger the intermediaries, the more distorted the prices; the more distorted the prices, the harder it becomes for mainstream funds to assess and enter using "normal market" methods, creating a vicious cycle. This process is not a matter of "the market not recognizing privacy," but rather a result shaped by institutional and channel structures.

Therefore, evaluating the Monero model should not remain in moral debates but should return to the reality constraints of institutional compatibility: complete anonymous privacy is "default safe" in the personal world, but "default unavailable" in the institutional world. The more extreme its advantages, the more rigid its dilemmas become. In the future, even if the narrative of privacy heats up, the main battleground for complete anonymous assets will still primarily be among non-institutional demand and specific communities; while in the institutional era, mainstream finance is more likely to choose "controllable anonymity" and "selective disclosure"—protecting business secrets and user privacy while being able to provide the evidence required for audits and regulation under authorized conditions. In other words, Monero is not a technical failure but is locked into a usage scenario that institutions find difficult to accommodate: it proves that strong anonymity is technically feasible, but it also clearly demonstrates that when finance enters the compliance era, the competitive focus of privacy will shift from "whether everything can be hidden" to "whether everything can be proven when needed."

2. The Rise of Selective Privacy

Against the backdrop of complete anonymous privacy gradually reaching an institutional ceiling, the privacy race has begun to shift direction. "Selective privacy" has become a new technical and institutional compromise path, with its core not being to counter transparency but to introduce a controllable, authorized, and disclosable privacy layer on top of a default verifiable ledger. The fundamental logic of this shift is that privacy is no longer seen as a tool for evading regulation but is redefined as an infrastructural capability that can be absorbed by institutions. Zcash is the most representative early practice in the selective privacy path. Its design, which coexists with transparent addresses (t-address) and shielded addresses (z-address), provides users with the freedom to choose between public and private transactions. When users utilize shielded addresses, the sender, receiver, and amount of the transaction are encrypted and stored on the chain; when compliance or audit needs arise, users can disclose complete transaction information to specific third parties through a "viewing key." This architecture is milestone in concept: it explicitly states for the first time in mainstream privacy projects that privacy does not have to come at the cost of verifiability, and compliance does not necessarily mean complete transparency.

From the perspective of institutional evolution, the value of Zcash lies not in its adoption rate but in its "proof of concept" significance. It proves that privacy can be an option rather than a system default state, and it also demonstrates that cryptographic tools can reserve technical interfaces for regulatory disclosures. This is particularly important in the current regulatory context: major global jurisdictions have not denied privacy itself but have rejected "un-auditable anonymity." The design of Zcash precisely addresses this core concern. However, as selective privacy transitions from "personal transfer tools" to "institutional trading infrastructure," the structural limitations of Zcash begin to emerge. Its privacy model essentially remains a binary choice at the transaction level: a transaction is either completely public or entirely hidden. For real financial scenarios, this binary structure is too crude. Institutional transactions involve not only the "two parties" information dimension but also multiple layers of participants and multiple responsible entities—counterparties need to confirm performance conditions, clearing and settlement institutions need to grasp amounts and timing, auditors need to verify complete records, and regulators may only care about the source of funds and compliance attributes. The information needs of these entities are both asymmetric and not entirely overlapping.

In this context, Zcash cannot componentize transaction information and authorize it differently. Institutions cannot simply disclose "necessary information" but must choose between "full disclosure" and "full concealment." This means that once entering complex financial processes, Zcash either exposes too much commercially sensitive information or fails to meet the most basic compliance requirements. Its privacy capabilities thus struggle to be embedded in real institutional workflows and can only remain at the level of marginal or experimental use. In stark contrast is the alternative selective privacy paradigm represented by the Canton Network. Canton does not start from "anonymous assets" but directly takes the business processes and institutional constraints of financial institutions as its design starting point. Its core idea is not to "hide transactions" but to "manage information access rights." Through the smart contract language Daml, Canton breaks a transaction into multiple logical components, allowing different participants to see only the data segments relevant to their permissions, while the remaining information is isolated at the protocol level. This design brings about a fundamental change. Privacy is no longer an additional attribute after a transaction is completed but is embedded into the contract structure and permission system, becoming part of the compliance process.

From a broader perspective, the differences between Zcash and Canton reveal the divergent directions of the privacy race. The former still relies on the crypto-native world, attempting to find a balance between personal privacy and compliance; the latter actively embraces the real financial system, engineering, processing, and institutionalizing privacy. As institutional funds continue to rise in the crypto market, the main battleground of the privacy race will also shift accordingly. The future competitive focus will no longer be on who can hide the most thoroughly, but on who can be regulated, audited, and widely used without exposing unnecessary information. Under this standard, selective privacy is no longer just a technical route but a necessary path to mainstream finance.

3. Privacy 2.0: Upgrading from Transaction Hiding to Privacy Computing Infrastructure

When privacy is redefined as a necessary condition for institutions to go on-chain, the technical boundaries and value extension of the privacy race also expand. Privacy is no longer merely understood as "whether transactions can be seen," but begins to evolve towards more fundamental questions: can the system complete computation, collaboration, and decision-making without exposing the data itself? This shift marks the transition of the privacy race from the 1.0 stage of "privacy assets / privacy transfers" to the 2.0 stage centered on privacy computing, where privacy upgrades from an optional feature to a universal infrastructure. In the privacy 1.0 era, the technical focus was mainly on "what to hide" and "how to hide," that is, how to obscure transaction paths, amounts, and identity associations; while in the privacy 2.0 era, the focus shifts to "what can still be done in a hidden state." This distinction is crucial. Institutions do not only need private transfers; they need to complete complex operations such as transaction matching, risk calculation, clearing and settlement, strategy execution, and data analysis under the premise of privacy. If privacy can only cover the payment layer but cannot cover the business logic layer, then its value to institutions remains limited.

Aztec Network represents the earliest form of this shift within the blockchain system. Aztec does not view privacy as a tool against transparency but embeds it as a programmable attribute of smart contracts within the execution environment. Through a zero-knowledge proof-based Rollup architecture, Aztec allows developers to finely define which states are private and which are public at the contract level, thus achieving a mixed logic of "partial privacy, partial transparency." This capability enables privacy to extend beyond simple transfers to cover complex financial structures such as lending, trading, treasury management, and DAO governance. However, Privacy 2.0 does not stop at the blockchain-native world. With the emergence of AI, data-intensive finance, and inter-institutional collaboration needs, relying solely on on-chain zero-knowledge proofs has become insufficient to cover all scenarios. Consequently, the privacy race has begun to evolve towards a broader "privacy computing network." Projects like Nillion and Arcium have emerged in this context. The common characteristic of these projects is that they do not attempt to replace blockchain but exist as a privacy collaboration layer between blockchain and real-world applications. Through a combination of multi-party secure computation (MPC), fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), and zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP), data can be stored, invoked, and computed in an encrypted state, allowing participants to jointly complete model inference, risk assessment, or strategy execution without accessing the raw data. This capability upgrades privacy from a "transaction layer attribute" to a "computation layer capability," and its potential market expands to areas such as AI inference, institutional dark pool trading, RWA data disclosure, and inter-enterprise data collaboration.

Compared to traditional privacy coins, the value logic of privacy computing projects has undergone significant changes. They do not rely on "privacy premiums" as a core narrative but on functional irreplaceability. When certain computations cannot be conducted in a public environment or would lead to serious business risks and security issues in plaintext, privacy computing is no longer a question of "whether it is needed," but rather "it cannot operate without it." This also gives the privacy race its first potential for a "foundational moat": once data, models, and processes are entrenched in a particular privacy computing network, the migration costs will be significantly higher than those of ordinary DeFi protocols. Another notable feature of the Privacy 2.0 stage is the engineering, modularization, and invisibility of privacy. Privacy no longer exists in the explicit forms of "privacy coins" or "privacy protocols," but is decomposed into reusable modules embedded in wallets, account abstractions, Layer 2, cross-chain bridges, and enterprise systems. End users may not even realize they are "using privacy," but their asset balances, trading strategies, identity associations, and behavioral patterns are protected by default. This "invisible privacy" aligns more closely with the realistic path to large-scale adoption.

At the same time, regulatory focus has also shifted. In the Privacy 1.0 stage, the core regulatory question was "is there anonymity"; in the Privacy 2.0 stage, the question has become "can compliance be verified without exposing raw data?" Zero-knowledge proofs, verifiable computation, and rule-level compliance have thus become key interfaces for privacy computing projects to engage with the institutional environment. Privacy is no longer seen as a source of risk but is redefined as a technical means to achieve compliance. Overall, Privacy 2.0 is not a simple upgrade of privacy coins but a systematic response to "how blockchain integrates into the real economy." It signifies a shift in the competitive dimensions of the privacy race from the asset layer to the execution layer, from the payment layer to the computation layer, and from ideology to engineering capability. In the institutional era, truly valuable privacy projects may not be the most "mysterious," but they will certainly be the most "usable." Privacy computing is a concentrated embodiment of this logic at the technical level.

4. Conclusion

In summary, the core watershed of the privacy race is no longer "whether there is privacy," but "how to use privacy under compliance." The complete anonymous model has irreplaceable security value at the personal level, but its institutional un-auditability determines its difficulty in supporting institutional-level financial activities; selective privacy provides a feasible technical interface between privacy and regulation through disclosable and authorized designs; and the rise of Privacy 2.0 further upgrades privacy from an asset attribute to a foundational infrastructure capability for computation and collaboration. In the future, privacy will no longer exist as an explicit function but will be embedded as a system default assumption in various financial and data processes. Truly valuable privacy projects may not be the most "secretive," but they will certainly be the most "usable, verifiable, and compliant." This is a key indicator of the privacy race transitioning from the experimental stage to the mature stage.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。