The Starting Point of Privacy — From Human Society to Digital Economy

Over the past century, humanity's understanding of "privacy" has continuously evolved. It is not just the right to be "hidden," but a deeper social consensus: we have the right to decide who can see our information, how much they can see, and when they can see it. This concept predates the internet and far predates blockchain.

In traditional society, privacy is primarily related to "trust." Banks are a typical example: when people deposit money in a bank, they are essentially handing over a part of their "life's secrets" to the institution — income, spending, debts, and even family structure. For this reason, Swiss banks established strict confidentiality systems in the last century, prohibiting any external entity from accessing customer information without permission. For the wealthy, this means asset security; for ordinary people, it is a matter of respect: my finances and information belong to me, not to the system.

Before the advent of digital currency, the ideal "privacy payment" tool was actually cash. Cash transactions have no identity, no trace, and no database — you give me 100 yuan, and no one else knows about it. Its anonymous nature brings both freedom and responsibility. For this reason, cash has always been retained in the global financial system, symbolizing a decentralized trust — interpersonal credit that does not require third-party endorsement. However, with the electronic and online nature of payments, this anonymous freedom is gradually being eroded.

Entering the internet era, data has become the new "oil." Every click, payment, and location can be collected. We exchange "free" applications, cashless payments, and convenient cloud services for efficiency, but we also trade away our privacy. In this sense, privacy is no longer a right but a commodity to be bought and sold. In 2018, Europe launched the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), requiring companies to obtain explicit consent before collecting personal data, with the core logic being: privacy is not an accessory, but an individual's ownership of their own information. However, this institutional protection still remains within a centralized framework — data is still controlled by platforms, and users can only "authorize" but cannot truly "control."

The meaning of privacy has become unprecedentedly complex in the digital world. We want to publicly identify ourselves to participate in transactions while also hoping to retain a space that is not subject to scrutiny. This is the core contradiction of the digital economy: systems require transparency to prevent fraud, while individuals desire privacy for security. Thus, people begin to rethink how to find a new balance between transparency and protection.

BenFen public chain has emerged in this context, viewing privacy payment as a core native capability, aiming to restore users' control over digital assets.

From Trust to Transparency — The Original Logic of Blockchain Design

If privacy is the right of "self-control" in human society, then transparency is the mechanism for establishing "common trust" in the blockchain world. To understand the root of privacy loss in blockchain, we must return to its original design logic — why it chose a "completely open" ledger structure.

In traditional financial systems, the source of trust is institutions. Banks, payment companies, clearinghouses, and other centralized entities are responsible for recording and verifying every transaction. In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto proposed a new trust architecture in the Bitcoin white paper: allowing people to conduct peer-to-peer value transfers without relying on financial institutions. In the absence of a central authority, how does the system maintain order? The answer is transparency: the ledger is public, transactions are verifiable, and history is traceable.

Blockchain enables each node to independently verify the authenticity of transactions through consensus mechanisms and cryptographic technology. Each transaction is packaged into a block, which is then linked in a chain structure via hashing, making it nearly impossible to tamper with. Thus, trust no longer relies on institutions but stems from the transparency of algorithms and the openness of rules. This design brings unprecedented security and verifiability, forming the trust foundation of the crypto economy.

The power of transparency has been fully demonstrated in practice. All historical transactions of public chains like Bitcoin and Ethereum can be publicly queried; anyone can verify transactions and trace the flow of funds through block explorers. For users, transparency brings fairness — there are no hidden ledgers or privileged transactions; for developers, it allows smart contracts to be externally audited; for the entire ecosystem, transparency builds a public layer of trust, enabling collaboration between strangers without relying on intermediaries. The prosperity of decentralized finance (DeFi) is a natural extension of this logic: every operation in the system can be verified, and trust is guaranteed by code rather than institutional endorsement.

The Cost of Transparency — The Real Issues of Privacy Loss

Transparency does not come without a cost. The public ledger of blockchain, while establishing trust and security, also conceals the deep cost of privacy loss. Every transaction and every address is permanently recorded on the chain, and this "complete transparency" structure means — as long as someone is willing to analyze, they can piece together wealth distribution, behavioral trajectories, and even personal identities.

In an ideal state, on-chain addresses are anonymous. However, in reality, the distance between anonymity and real identity is often just a few steps. Analysis companies like Chainalysis and Arkham have demonstrated how to associate multiple wallets with the same entity through transaction clustering and address profiling. Once combined with external data such as social media, email registrations, or NFT transaction records, identities are no longer secret.

This risk has already caused harm in reality. In a 2025 crypto kidnapping case in Manhattan, New York, an Italian man was lured and coerced by two crypto investors to hand over his Bitcoin wallet password. The suspects inferred that the victim held a large amount of digital assets through publicly available on-chain data and identity clues, making him a target. Such incidents indicate that when wealth and transaction behavior are publicly traceable on-chain, transparency can be exploited by criminals, posing real-world threats.

Transparency also brings economic unfairness. In decentralized finance, the so-called "Maximum Extractable Value (MEV)" phenomenon allows certain high-frequency traders to front-run or arbitrage before ordinary users by listening to transaction pool information. Transparency here becomes a tool for plunder rather than a guarantee of trust. Meanwhile, on-chain activities of enterprises may leak trade secrets, supply chain information, or salary structures, while personal account transaction records expose consumption habits and investment preferences, creating new data risks.

Therefore, a transparent ledger is not purely good. It solves the "trust issue" but creates a "privacy crisis." More and more users and institutions are beginning to realize that a transparent system without privacy protection cannot support the complex economic activities of the real world. BenFen privacy payment thus emerges: achieving transaction anonymization without sacrificing verifiability, allowing users to retain true privacy sovereignty on-chain. Privacy payment is therefore not just a functional innovation but a necessary prerequisite for the sustainable development of blockchain — only in a system where security and privacy are compatible can trust truly be solidified.

The Definition and Value of Privacy Payment

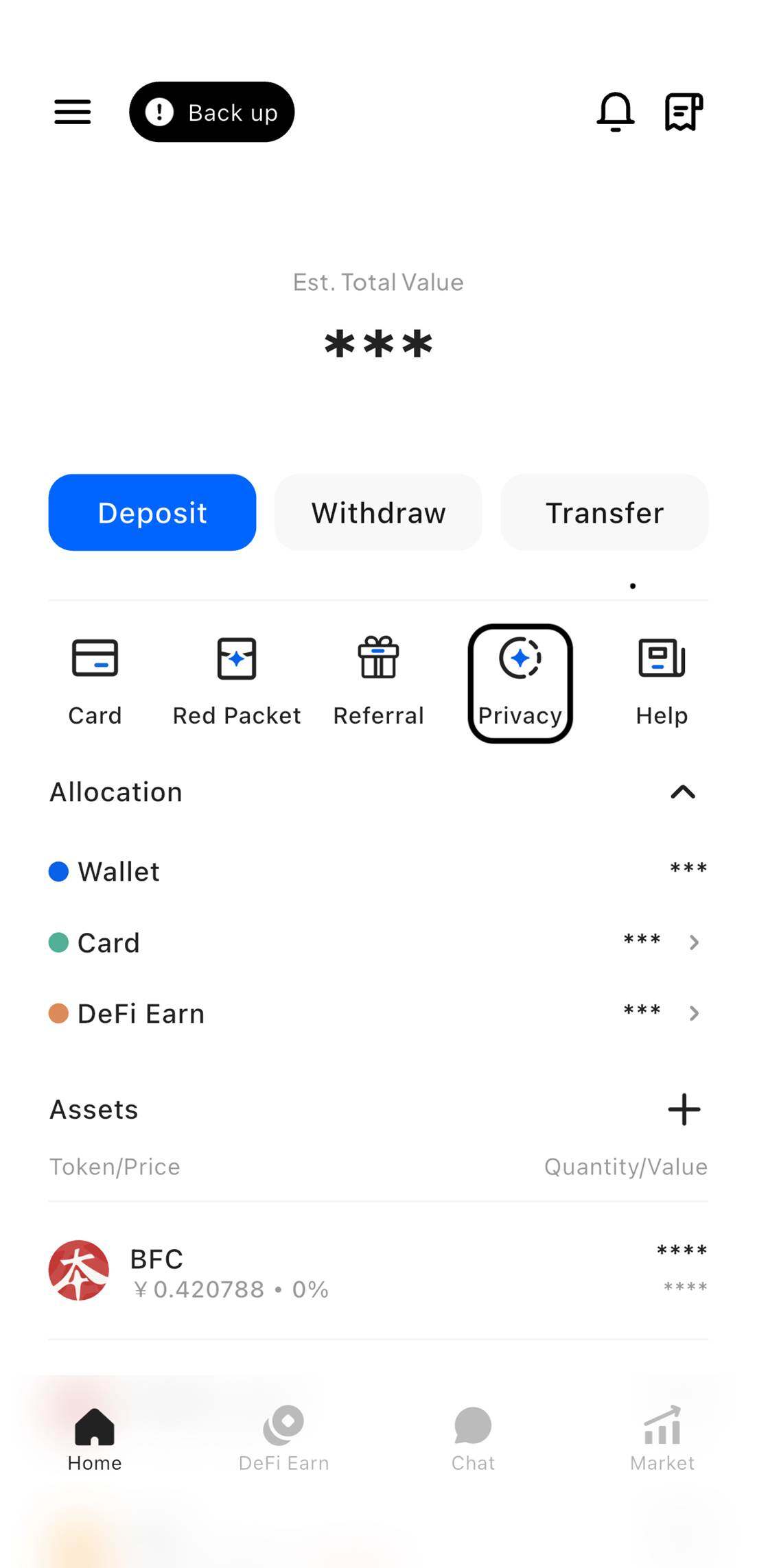

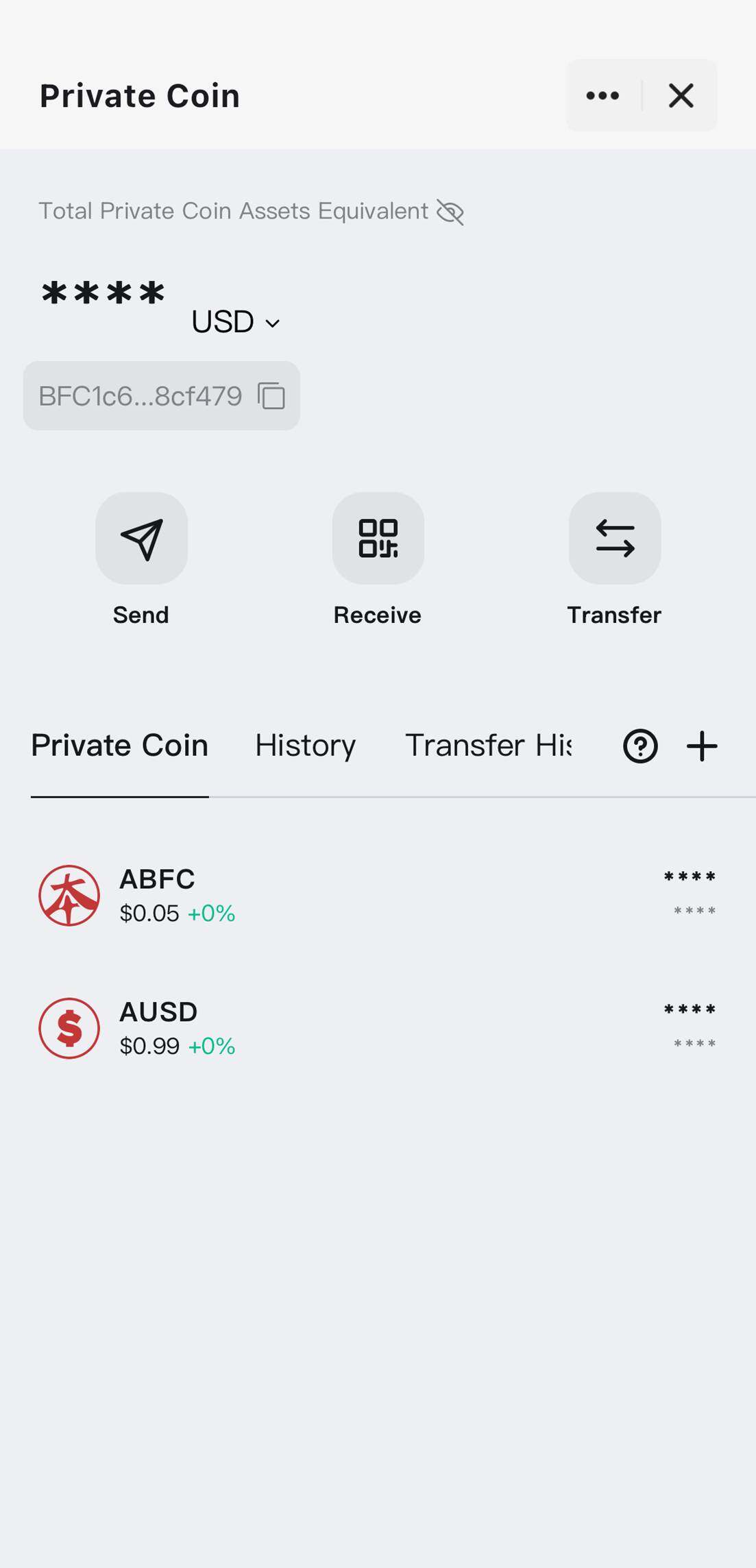

Before understanding privacy payment, we must distinguish between two concepts: privacy transaction and user privacy. Privacy transaction refers to the protection of information for a single transaction, such as hiding the source of a transaction in Bitcoin through mixing techniques, preventing that payment from being traced on-chain. User privacy is broader, referring to the protection of the entire account or user behavior, including long-term transaction patterns, asset distribution, and identity information. Imagine an ordinary consumer: they use a digital wallet to buy coffee, pay rent, or order takeout in daily life. If every transaction can be fully tracked, not only are consumption habits exposed, but it may also indirectly reveal income status or family structure. The goal of privacy payment is to ensure that user behavior patterns and personal information are not recorded and analyzed long-term while ensuring the validity and legality of transactions.

Privacy has three core value dimensions in payment networks. First is identity privacy, which ensures that user identities are not directly linked to transactions. A relatable example is that when users pay friends or merchants, they do not want their names, addresses, or contact information to be known by unrelated third parties. Second is amount privacy, which protects transaction amounts from being disclosed. For instance, if someone pays a gift or investment amount from their digital wallet, exposing the amount could lead to targeted scams or social pressure. Finally, there is transaction relationship privacy, which avoids external analysis of transaction patterns. For example, if payments to a certain supplier are consistently tracked, it could leak business strategies, supply chain layouts, or personal consumption preferences.

The social and commercial value of privacy payment is reflected on multiple levels. For ordinary users, it reduces the risk of identity misuse or precise location tracking, making digital payments safer and freer; for merchants and small businesses, privacy payment can protect customer information and transaction data, preventing competitors from spying on sales figures or supply chain arrangements; for cross-border enterprise payments, privacy payment can meet regulatory compliance requirements without disclosing transaction amounts or counterpart information, thus reducing operational costs. For example, a cross-border trading company can complete settlements with overseas suppliers through privacy payment, avoiding exposure of profit margins and payment frequencies while ensuring tax compliance. In daily life, a user making anonymous payments for subscription fees or online shopping in a digital wallet can enjoy similar protections, preventing consumption habits from being captured and analyzed by advertisers or social platforms.

Privacy payment not only helps protect personal information but also enhances network activity and trust. People are more willing to transact in a secure network that can protect behavioral patterns, which directly affects the adoption rate and economic vitality of payment networks. Research shows that digital payment users are significantly more willing to use a network that supports privacy protection. This trust comes not only from technological guarantees but also from users' awareness of data control rights. In other words, privacy payment is not just about anonymizing a single transaction but is a form of long-term, systematic protection of behavioral patterns.

It is important to emphasize that privacy payment does not mean it cannot be regulated or does not comply with legal requirements. Through zero-knowledge proofs, multi-party computation, and consent disclosure mechanisms, transaction networks can achieve audit and compliance requirements without exposing sensitive information. While users enjoy privacy protection, necessary information can still be authorized for disclosure to regulators or auditors, ensuring that payment behaviors are legal, transparent, and controllable. This design not only resolves the contradiction between privacy and compliance but also provides a foundation for the widespread application of blockchain payment networks.

BenFen is a typical practitioner of this concept: its privacy payment combines zero-knowledge proofs and multi-party computation mechanisms to achieve comprehensive concealment of transaction amounts, sender and receiver addresses, while supporting regulatory authorities to conduct selective audits through a view key, ensuring compliance without sacrificing user privacy.

The Evolution of Blockchain Privacy — From Anonymous Coins to Modular Infrastructure

Anonymous Coin Stage: Initial Practice of Privacy Concepts

The earliest attempts at blockchain privacy were anonymous coins, whose core goal was to protect the identities of both parties in a transaction and the transaction amounts. Monero, released in 2014, is one of the first cryptocurrencies to achieve on-chain privacy transactions, with core mechanisms including ring signatures and stealth addresses. The sender's input for each transaction is mixed with multiple historical inputs to generate a ring signature, thus hiding the true sender and avoiding direct association of the transaction parties on-chain. The receiver uses a one-time stealth address to receive funds, ensuring that the payment path cannot be directly identified by external observers. Nevertheless, if on-chain information is combined with off-chain data (such as exchange KYC information, social media, or NFT transaction records), there may still be some tracking risks. Its limitations are also quite evident: the transaction data size is large, and block bloat is significant (the size of a single transaction is significantly larger than that of a Bitcoin transaction); at the same time, Monero does not support complex smart contracts, limiting its usability in decentralized finance (DeFi) and other application scenarios.

Zcash introduced zero-knowledge proofs (zk-SNARKs) in 2016, allowing users to generate mathematical proofs that verify the legality of transactions while hiding transaction amounts and participant identities. Unlike Monero, Zcash offers a "selective transparency" mechanism, meaning users can choose shielded transactions for privacy protection. This technology theoretically guarantees both transaction validity and privacy, but generating proofs requires high computational resources, leading to noticeable transaction delays, which poses challenges for ordinary user experience. Early adoption rates were also relatively low, reflecting the trade-off between privacy protection and usability.

The anonymous coin stage laid the conceptual foundation for blockchain privacy: it directly and clearly proposed the idea of "protecting user security by hiding information," providing technical and conceptual references for subsequent protocol layer privacy and privacy computing stages. At the same time, this stage also exposed the contradictions between privacy protection and scalability, user experience, prompting designers to find a balance between privacy, security, and usability.

Protocol Layer Privacy: Meeting Smart Contract Needs

With the rapid development of smart contracts and decentralized finance (DeFi), the limitations of early anonymous coins in privacy protection gradually became apparent. While anonymous coins like Monero or Zcash can effectively hide the identity and amount of a single transaction, they cannot be directly applied in scenarios involving smart contract interactions, complex asset management, and multiple transaction aggregations. To meet the privacy needs of complex on-chain applications, protocol layer privacy tools emerged.

Tornado Cash is a mixing protocol based on Ethereum that disrupts transaction paths through mixing pools and zero-knowledge proofs, achieving decoupling of senders and receivers, making the flow of funds difficult to trace. It provides users with a practical case of on-chain privacy transactions. However, Tornado Cash also faces real regulatory risks: in 2022, the U.S. Treasury placed it on the sanctions list, indicating that protocol layer privacy faces compliance challenges. Additionally, Tornado Cash only mixes transactions and does not support privacy operations for complex smart contracts.

Railgun provides DeFi users with multi-asset privacy trading and smart contract interaction capabilities, supporting token types such as ERC-20 and ERC-721. Users can hide their identity, amount, and transaction relationships while meeting some audit and compliance needs through authorized interfaces. However, Railgun's cross-chain support is limited, primarily focusing on EVM-compatible ecosystems, and its usage threshold is relatively high.

Overall, the core significance of the protocol layer privacy stage lies in enhancing privacy protection in on-chain applications, making the flow of funds and user behavior in smart contracts and DeFi scenarios difficult to trace. The limitations of this stage mainly include operational complexity, high computational and gas costs, limited cross-chain support, and real regulatory risks. These constraints provide clear directions for the development of subsequent privacy computing and modular privacy infrastructure, highlighting the inevitability of the evolution of blockchain privacy technology from single transaction protection to a verifiable, multifunctional privacy system.

In the evolution of this stage, BenFen's privacy payment function focuses on achieving efficient on-chain anonymous transactions, supporting users in seamlessly transferring funds while hiding their identity and amount, aiming to solve the convenience issues of traditional anonymous coins in mobile payments and daily use, further expanding the application of anonymous coins in payment scenarios.

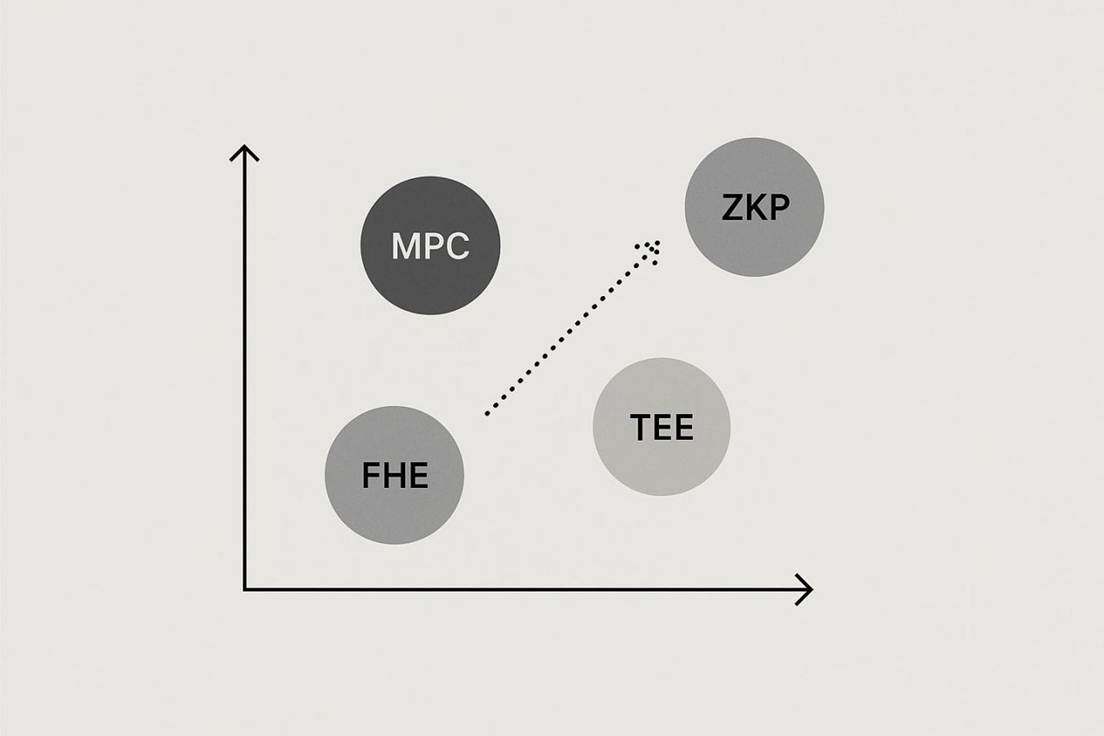

Privacy Computing Stage: Verifiable + Privacy

Protocol layer privacy focuses more on hiding transaction data, while the emergence of privacy computing allows blockchain to transition from "information concealment" to "computational verifiability." It ensures that data remains confidential while allowing the correctness of results to be verified by completing computations in an encrypted state, making privacy protection for complex smart contracts, multi-party collaboration, and cross-chain operations possible. Current major privacy computing technologies include zero-knowledge proofs (ZK), trusted execution environments (TEE), and secure multi-party computation (MPC), each representing different technical paths and methods for implementing privacy payments, which will be detailed later.

Trusted Execution Environment (TEE)

Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) relies on hardware isolation mechanisms to execute sensitive computations within a secure area of the CPU, making data inaccessible from the outside, thus achieving hardware-level privacy. Representative projects include Oasis Network, Secret Network, and Phala Network.

Oasis Network: A Privacy Computing Platform with a Flexible Architecture

Development Timeline: The project mainnet officially launched in November 2020. An important milestone was the launch of Sapphire ParaTime in 2022, which is an EVM-compatible privacy blockchain that significantly lowers the development threshold.

Core Features and Architecture:

○Separation of Consensus and Execution: This is the core innovation of Oasis. The network is divided into a consensus layer and multiple parallel ParaTime execution layers. The consensus layer is operated by validators, responsible for security and stability; the ParaTime layer is operated by independent node operators, responsible for handling smart contracts and other computational tasks. This design allows multiple ParaTimes to process transactions in parallel, greatly enhancing scalability.

○Sapphire ParaTime: As a key product in the privacy track, it allows developers to use standard tools like Solidity to write smart contracts that can encrypt states and private transactions, achieving "out-of-the-box" privacy functionality.

Applications and Ecosystem: With its flexible architecture, Oasis has a profound layout in the field of data tokenization, aiming to build a responsible data economy. Collaborative cases include developing data spaces in partnership with BMW Group and protecting user genetic data privacy in collaboration with Nebula Genomics.

Challenges: Its TEE implementation relies on specific hardware (such as Intel SGX), posing risks of data leakage due to chip vulnerabilities; at the same time, its cross-chain ecosystem is still in the construction phase compared to leading public chains.

Secret Network: A Smart Contract Public Chain with "Default Privacy" Features

Development Timeline: Its predecessor, Enigma, was launched in 2017, and the mainnet started in September 2020, being the first blockchain with privacy-protecting smart contracts. Later, its Secret Ethereum Bridge was launched, enhancing cross-chain capabilities.

Core Features: As the first blockchain in the Cosmos ecosystem to emphasize "default privacy," its "Secret Contracts" ensure that contract states and input data are processed in an encrypted state, viewable only by authorized parties. BenFen implements similar default privacy on Move VM, hiding amounts and balances during transfers and providing temporary visible authorization.

Applications and Ecosystem: Naturally suitable for privacy DeFi, privacy NFTs, and privacy transfers, its ecosystem applications inherently possess privacy protection attributes from inception.

Challenges: It faces hardware trust and vulnerability risks associated with Intel SGX. Additionally, its primary challenge lies in attracting more developers to build a more prosperous ecosystem to demonstrate the widespread value of "default privacy."

Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZK)

Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) allows users to prove the truth of a statement to the outside world without revealing the original information. It was first proposed in academia but has been widely used in blockchain for privacy payments and scalability design. Typical representatives include Aleo and Aztec.

Aleo: Off-Chain Computing and Privacy Smart Contracts

Development Timeline: The project was launched in 2019, with the mainnet set to go live in 2024. Aleo is one of the first public chains to apply ZK technology to the privacy computing layer.

Core Features: All computations are completed off-chain, with only zero-knowledge proofs verified on-chain, protecting data privacy while reducing blockchain load. Its dedicated programming language Leo allows developers to easily build applications for privacy payments, DeFi, identity verification, etc., lowering the development threshold.

Applications and Ecosystem: After the mainnet launch, the community saw the emergence of private payment wallets, anonymous voting, and private DeFi prototype applications.

Challenges: The high computational overhead of generating zero-knowledge proofs makes it difficult to run on mobile and low-power devices, and the ecosystem is still in its early stages.

Aztec: Privacy Payments in the Ethereum Ecosystem

Development Timeline: The Aztec project was launched in 2017, with version 2.0 going live on the mainnet in 2021.

Core Features: By combining zkSNARK and rollup technology, multiple private transactions are packaged to generate a unified proof, which is then submitted to the Ethereum mainnet, achieving privacy protection and reducing gas costs.

Applications and Ecosystem: Aztec Connect once supported users in making anonymous payments and yield farming operations on Ethereum but suspended operations in 2023.

Challenges: There remains a trade-off between privacy, regulation, and performance, while the developer ecosystem needs further improvement.

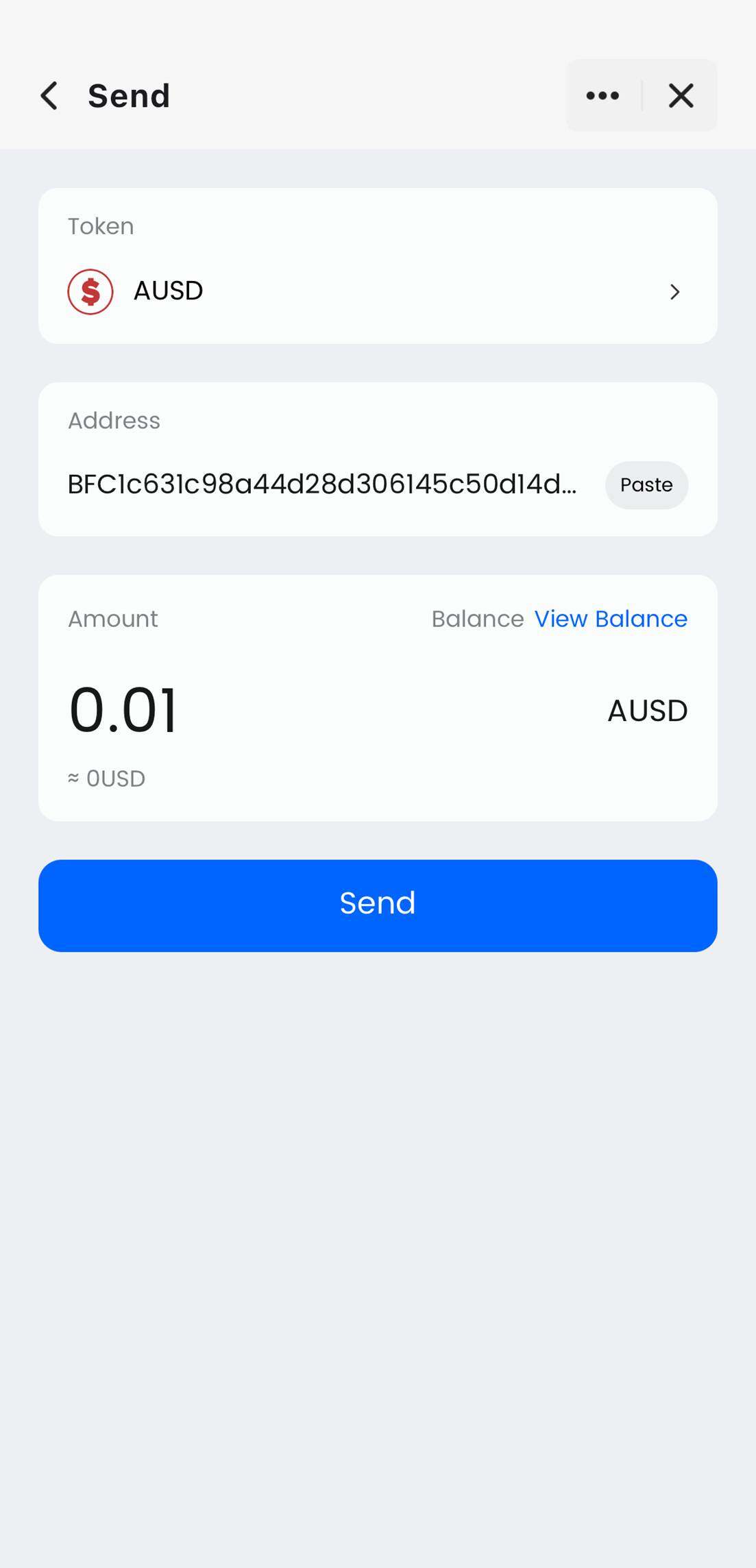

Overall, the ZK technology route possesses high security and mathematical verifiability in privacy payments, making it particularly suitable for payment systems that require high privacy protection and verifiability. Its development history demonstrates a gradual transition from academic prototypes to commercial applications, providing a technical foundation for subsequent Layer 2 privacy payments and complex smart contracts. BenFen's privacy payment function further evolves on this basis: by deeply integrating MPC protocols, zero-knowledge proofs, and the native privacy coin AUSD, it collaboratively generates private transactions off-chain. The system converts core elements such as input amounts, output amounts, sender/receiver addresses, and asset types into encrypted commitments or privacy states, using AUSD as the carrier of hidden assets, ensuring that the flow of funds in transactions cannot be identified externally. Only the final verified state changes are synchronized on-chain, with nodes only verifying the correctness of the transformations, thus preventing the reverse derivation of original information, fundamentally blocking on-chain data analysis and achieving stronger asset and identity privacy protection.

Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC)

Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC) allows multiple parties to jointly compute a function and obtain results without revealing their individual input data. It is currently one of the technologies closest to commercial application in the field of privacy payments. Unlike ZK (which typically requires trusted setup) and TEE (which relies on specific hardware), MPC primarily achieves privacy protection through distributed algorithms, usually not depending on complex pre-existing trust assumptions. Representative projects include Partisia Blockchain and Lit Protocol.

Partisia Blockchain: A Public Chain Featuring MPC

Development Timeline: Partisia is one of the earliest projects to systematically apply MPC technology to the underlying architecture of blockchain.

Core Features: Its goal is to build a public chain with MPC as its core functionality. By combining threshold signatures (a specific application of MPC) and secret sharing, it distributes transaction signatures and complex computational tasks across different nodes, thereby avoiding single-point privacy leaks. The algorithm employs a hybrid MPC model and optimizes efficiency using homomorphic encryption and other solutions.

Applications and Ecosystem: Its MPC payment protocol has been piloted in scenarios such as decentralized advertising settlement, supporting verification and accounting without disclosing sensitive business data (such as specific amounts). This design makes it an ideal choice for cross-institutional data collaboration and enterprise-level payment solutions.

Challenges: The main bottleneck of MPC lies in high computational and communication overhead, as multi-party computation protocols require frequent inter-node interactions, leading to high latency and strict network conditions. Even though Partisia has optimized algorithm efficiency, it still faces performance challenges in large-scale public chain environments that require low latency.

Overall, the MPC route represents a profound shift from institutional trust to algorithmic trust. It is not only used for payment signatures and settlements but is also gradually expanding into identity verification, data sharing, and cross-border payment fields. To overcome performance bottlenecks, the industry is also exploring "hybrid privacy architectures," such as combining MPC with ZK to use ZK proofs to compress verification steps, thereby accelerating the final confirmation process while ensuring privacy. BenFen has successfully broken through performance bottlenecks through the MPC+ZK hybrid architecture, becoming a new generation of public chain infrastructure that combines privacy protection with high-performance execution capabilities.

Compared to ZK's "zero-knowledge proof" and TEE's "hardware black box," the core advantage of MPC lies in "decentralized collaboration." It is most suitable for privacy payment systems that require multi-party participation, complex account management, and compliance audit needs. Therefore, MPC plays a role as a "bridge connecting traditional finance and the crypto world" in the evolution of privacy payments, providing a solid foundation for subsequent technical solutions.

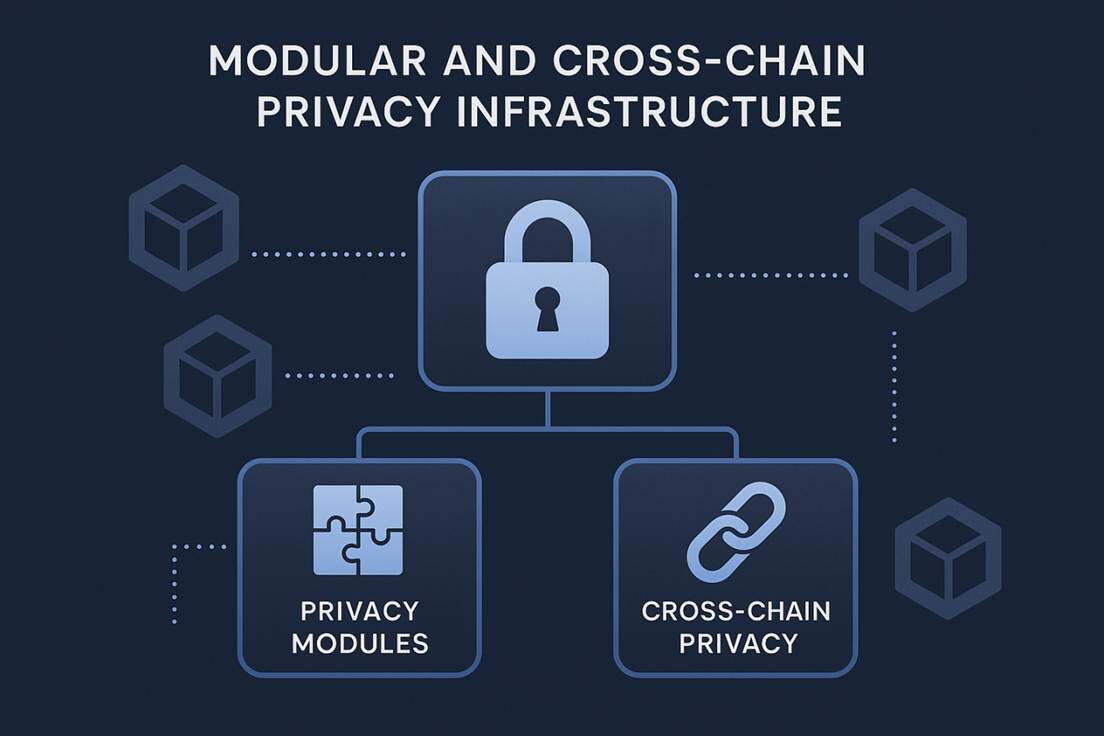

Modular and Cross-Chain Privacy Infrastructure

With the development of blockchain privacy technology, a trend of modular and cross-chain privacy infrastructure has emerged. Modular privacy infrastructure abstracts privacy functions from single chains or applications into reusable components, lowering development thresholds and enabling developers to easily build privacy applications. For example, Aleo provides reusable privacy smart contract modules to implement private transactions and privacy smart contract functionalities. Cross-chain privacy attempts to achieve the transfer of privacy assets and partial contract interactions between different blockchains, with Oasis's Privacy Layer designed to allow other chains/dApps to access privacy functions (through bridging/message layers) to utilize its privacy ParaTime capabilities. However, the protocol is complex, and cross-chain security and standardization still need improvement.

This trend indicates that privacy is rising from single transaction protection to infrastructure-level capabilities, capable of supporting diverse scenarios such as DeFi, privacy payments, data trading, and digital identity. However, modular and cross-chain privacy still faces challenges such as small ecosystem scale, insufficient standardization, cross-chain security risks, and interoperability limitations. Despite the enormous technical potential, continuous improvement and validation are still needed before large-scale applications can be realized.

Technical Route Comparison: How to Achieve Privacy Payments?

Zero-Knowledge Proof

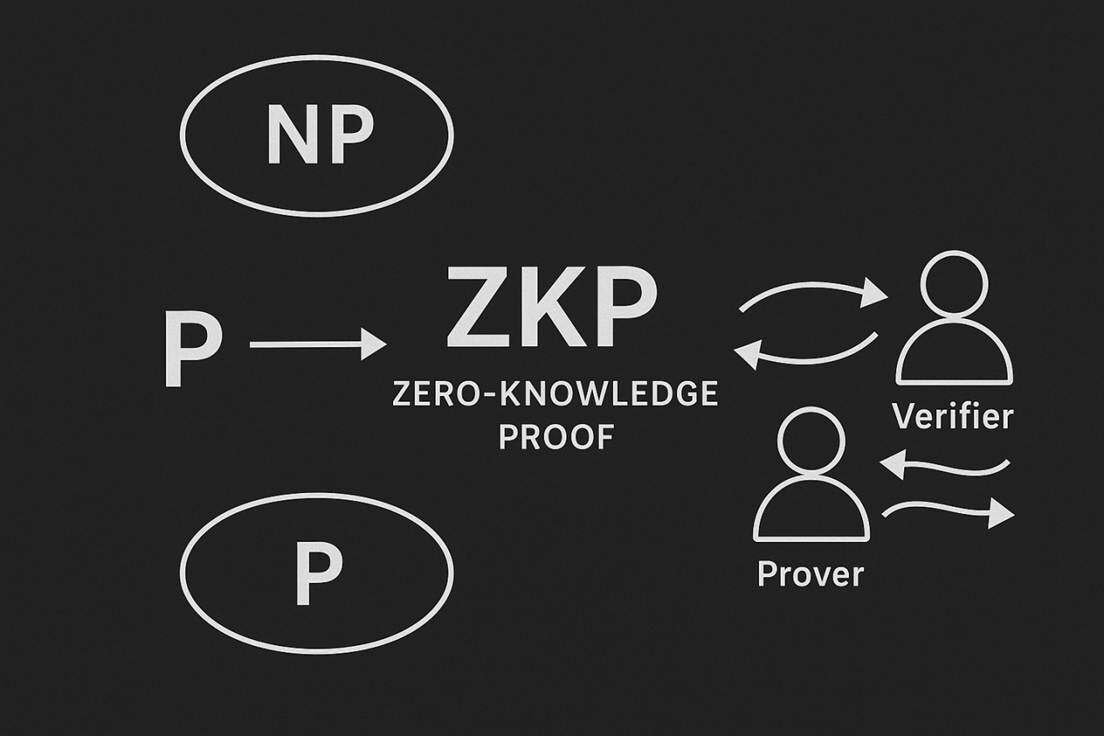

Zero-knowledge proofs are closely related to NP problems, so before entering this module, please allow me to introduce a mathematical problem: P vs NP.

As the foremost of the seven Millennium Prize Problems, P vs NP is widely known, but due to the simplicity of its expression, most people do not understand what P=NP means. P stands for Polynomial Time, which can be simply understood as problems that can be solved quickly. NP stands for Nondeterministic Polynomial Time, which can be simply understood as problems that can be verified quickly. Therefore, the actual statement of the P vs NP problem is whether there exists a hidden method to quickly solve a problem that can be verified quickly, and whether these two capabilities are equivalent. If P=NP, then problems that currently seem difficult to solve, such as combinatorial optimization problems in logistics scheduling, could be solved by a very amusing algorithm. However, correspondingly, this would deal a fatal blow to the field of cryptography based on large integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems, as hackers would always find a fast algorithm to crack private keys or reverse-engineer ciphertexts. The current mainstream view is that P and NP are not equivalent, meaning we must accept that many problems in the world simply do not have efficient algorithms, and we must continuously approximate, never finding the optimal solution.

The traditional NP verification approach is very straightforward, consisting of only two steps:

Provide a certificate: For an instance of an NP problem, if its answer is "yes," there must exist a short, efficiently checkable "evidence," which is the certificate.

Run the verification algorithm: There exists a deterministic algorithm that takes the problem instance itself and the candidate certificate as input. If the certificate is indeed a valid solution to the problem, the algorithm will output "yes" in polynomial time; otherwise, it will output "no."

However, this verification approach has two significant drawbacks: the privacy leakage of certificate information and the one-time passive acceptance of the certificate.

To address these issues, zero-knowledge proofs emerged. The concept of zero-knowledge proofs was formally proposed and defined in the 1985 paper "The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof Systems," and the final version was published in the Journal of the ACM in 1989. In this paper, authors Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Charles Rackoff (GMR) introduced two revolutionary concepts: interactive proof systems and knowledge complexity.

Traditional NP verification is static, one-time, passive, and deterministic. In contrast, interactive proofs are dynamic, multiple, active, and probabilistic. In this system, there is a prover P and a verifier V, where V randomly challenges P multiple times to ensure with high probability that P is correct. The logic is that if P's proposition is correct, then P can answer any question related to that proposition. If V's questions to P are all accurately answered, then V will likely believe that P's proposition is correct. Interactive proof systems must possess completeness and soundness, meaning that if the statement is true, an honest P can interactively convince V to accept with a very high probability, while if the statement is false, any P has a negligible probability of convincing V to accept after interaction.

In traditional proofs, people only care about whether the proof is valid and the logic is correct, but GMR raised a deeper question: when a verifier believes a statement to be true, what additional knowledge does he gain beyond this binary conclusion? That is, how much information is leaked during the proof process itself. Knowledge complexity is proposed as a metric to quantify this information leakage. Notably, a knowledge complexity of zero means that the verifier gains no additional information beyond the accuracy of the statement, hence "zero knowledge."

zk-SNARK: Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge

The interactive proof system proposed by GMR revolutionized the understanding of the concept of proof, but it has its own cumbersome flaws: interactivity requires P and V to be constantly online and continuously transmitting information, and the proof process lacks repeatability, making effective large-scale broadcasting impossible.

To address these shortcomings, Blum, Feldman, and Micali (BFM) proposed a conjecture: Is it possible to replace "interaction" with a method that allows the prover to independently generate a complete proof that anyone can verify? They provided a solution: a one-time, trusted setup phase needs to be introduced. This setup phase generates a Common Reference String (CRS). The CRS is a string of random, publicly available bits that is generated before any proof begins.

The workflow of the BFM scheme is as follows:

Setup Phase: A trusted party randomly generates a CRS and makes it public. This step only needs to be performed once.

Proof Generation: When the prover P wants to prove a statement, he no longer needs to wait for a challenge from the verifier. Instead, he uses the CRS as a source of randomness to simulate the challenges that the verifier might pose. P uses the CRS and his own secret information to independently compute a single, non-interactive proof.

Proof Verification: Any verifier V who receives the proof w uses the same CRS to verify the validity of w. Since the CRS is public, anyone who holds the CRS can act as a verifier.

In traditional verification of a complex computation, a significant amount of time and resources is consumed, which edge devices cannot afford. Therefore, the ideal verification state in people's eyes is that regardless of how complex the original computation is, the time and resources required for verification should be minimal and concise. In the 1990s, Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCP) were proposed, with the core idea being that any mathematical proof that can be verified in polynomial time (i.e., NP problems) can be transformed into a special encoded form. The verifier does not need to read the entire proof; instead, by randomly sampling a very small number of bits from this encoded proof, they can determine the correctness of the entire proof with a very high probability. This theorem is incredibly powerful, proving that there exists a method where the verification workload is essentially independent of the computational scale, which aligns with the pursuit of simplicity in verification. Although PCP and BFM's proposals were progressive, they remained at a theoretical level due to the technological limitations of the time and the lack of relatively mature cryptographic tools to combine with them, making practical application still a distant goal.

In 2012, the first truly realized zk-SNARK was proposed, namely the Pinocchio protocol. This was a groundbreaking breakthrough. The Pinocchio protocol provides an efficient compiler that can convert a piece of C code into the circuits and parameters required for zk-SNARK. It was the first to prove that zk-SNARK could be used to verify real-world computations; although the speed was still slow, it had transformed from a theoretical concept into a working prototype. At the same time, another independent work, GGPR, was also proposed, where the Quadratic Span Programs (QSP) and Quadratic Arithmetic Programs (QAP) introduced by Rosario Gennaro, Craig Gentry, Bryan Parno, and Mariana Raykova became the core technical foundation for most subsequent zk-SNARK systems.

Below is a separate introduction to these two works.

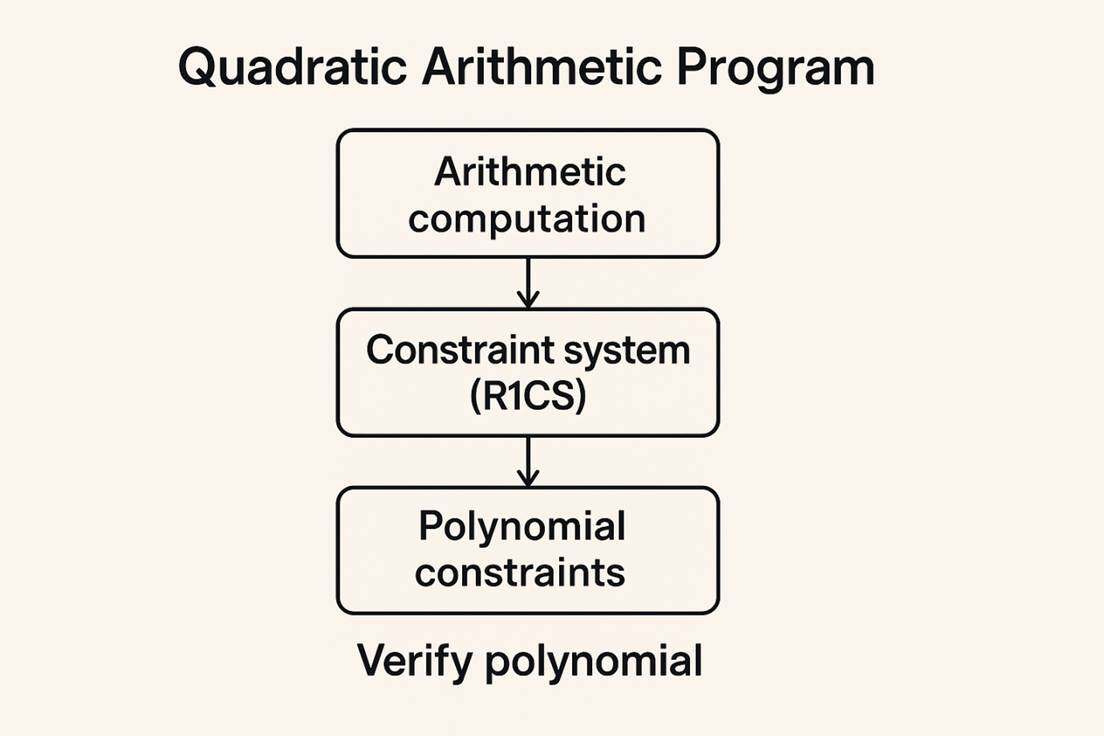

The purpose of both QSP and QAP is to transform different computational problems into polynomial problems, but as an improved version of QSP, QAP is more concise, more standardized, and has a broader application range, so we will focus only on QAP. QAP has a strong assumption that any computational problem solvable on a deterministic Turing machine within certain computational resources can be transformed into an equivalent arithmetic circuit concerning polynomial divisibility. The core process of QAP is as follows:

Decompose any computation into the most basic addition and multiplication operations.

Construct a constraint system (R1CS), establishing a set of quadratic equation constraints for each logic gate, i.e.,

Use Lagrange interpolation to transform R1CS into a continuous constraint concerning polynomials.

Verify the correctness of the polynomial.

In this way, we transform the proof of a computational problem into a polynomial problem, where the prover only needs to prove to the verifier that he knows the final constructed polynomial to complete the proof.

Based on the theoretical foundation of QAP, the Pinocchio protocol was constructed, which is a truly nearly practical verifiable computing system. It optimized the previous theoretical constructs and realized the first high-performance, general-purpose zk-SNARK prototype system, establishing the basic paradigm of modern zk-SNARK. In October 2016, the cryptocurrency Zcash was launched, which, by using zk-SNARKs, can be both public like Bitcoin and shielded, hiding the sender, receiver, and transaction amount.

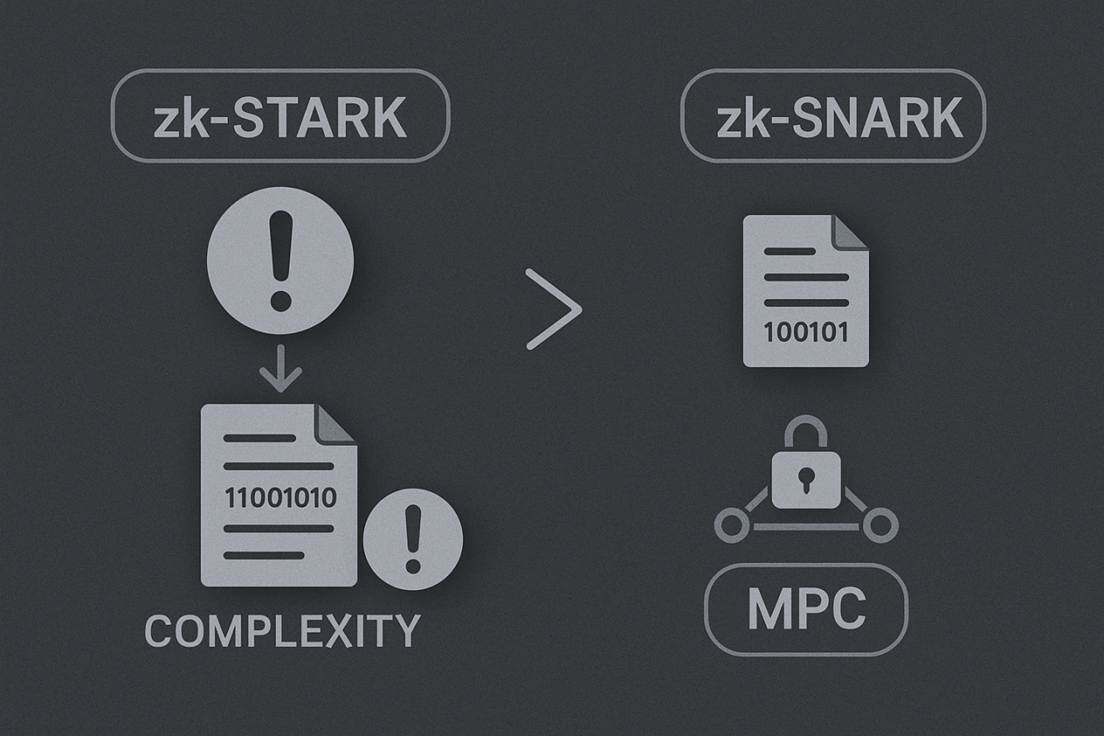

zk-STARK: Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge

Although Zcash achieved significant success, it also exposed some issues with zk-SNARK: the need for a trusted setup, poor scalability, and vulnerability to quantum computing, among others. Therefore, to address this series of problems, in 2018, Eli Ben-Sasson and others defined a brand new zero-knowledge proof construction called zk-STARK (Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge) in the paper "Scalable, Transparent, and Post-Quantum Secure Computational Integrity," where the three words in its full name correspond to three major innovations.

Transparency - How to eliminate the trusted setup?

Technical Core: Use a public random source (hash function) instead of a trusted setup.

Problem with zk-SNARK: Its security relies on a structured public reference string generated in a trusted setup. If this string is leaked by participants, it can be used to forge proofs.

Solution of zk-STARK:

- Completely discard elliptic curve pairings and structured reference strings.

- Use collision-resistant hash functions (such as SHA-256) as the only cryptographic primitive.

- All public parameters of the system (especially the "randomness" used for queries) are publicly and reproducibly derived during the proof generation process from the verifier's challenges and the hash function. No prior secret setup phase is needed.

Scalability - How to achieve logarithmic verification efficiency?

a. Algebraize the computational problem (AIR)

First, the paper introduces a method called Algebraic Intermediate Representation. It encodes the computation that needs to be proven as a set of polynomial constraints. These constraints describe the mathematical relationships that the program's state must satisfy at each step of the computation.

b. Use the FRI protocol for efficient verification

This is key to achieving "scalability." The FRI protocol is used to prove that a function is indeed a "low-degree polynomial." The entire process can be simplified into a multi-interactive "challenge-response" process.

Knowledge Proof - How is security guaranteed?

Meaning of "Knowledge Proof": In cryptography, "proof" usually refers to computationally sound proofs, meaning security relies on computational hardness assumptions. In contrast, information-theoretically sound "proofs" are unconditionally secure.

Security Model of zk-STARK:

- Its security is based on the computational hardness assumption of collision resistance of hash functions.

- It is a "knowledge" proof, meaning that if the prover indeed knows the "evidence" that satisfies the conditions, the verifier will accept the proof; if the prover does not know, the probability of successfully forging the proof is extremely low.

In the same year, Eli Ben-Sasson and others founded StarkWare to commercialize zk-STARK technology, developing a new programming language called Cairo and launching two core products, StarkEx and StarkNet, along with the issuance of the STRK token. After completing a Series D funding round in July 2022, StarkWare's valuation reached $8 billion.

Of course, zk-STARK also has its own issues. To achieve "transparency" (without a trusted setup), zk-STARK relies on cryptographic primitives such as hash functions and Merkle trees, resulting in a larger amount of data generated during the interactive proof process, with the size of the generated proof files typically in the hundreds of KB, which is much larger than zk-SNARKs' proofs (which are usually only a few hundred bytes). This significantly impacts on-chain transaction costs and transmission overhead. Additionally, since the proof generation process involves complex mathematical operations, the computational complexity is very high, requiring a large amount of computational resources to generate a zk-STARK proof, which indirectly raises the usage threshold for users.

Furthermore, it is important to note that both Zcash and StarkNet are based on zero-knowledge proof technology, but zero-knowledge proofs can only guarantee the privacy of transactions. There is actually no good solution for issues such as private key management, asset configuration, and recovery after unexpected events. The inherent flaws of ZKP mean that we must use other technologies in conjunction with ZKP to compensate for its shortcomings. Fortunately, MPC can provide an almost perfect solution, and the integration process with ZKP does not require a significant cost. Therefore, combining with MPC is a necessary path for ZKP, and we will further introduce relevant knowledge of MPC and provide specific integration solutions later.

Mixers & Ring Signatures

In short, mixers anonymize assets, obfuscating the source of funds, while ring signatures anonymize the sender of transactions, obscuring the true signer, but the implementation methods of the two are entirely different.

Mixers

a. Deposit (Commitment)

The user generates a secret s and computes its hash value commitment = Hash(s).

The funds are deposited into the contract along with the commitment. The contract publicly records the commitment.

b. Wait (Mixing)

- The user waits for other users to deposit funds to mix their transaction into a large "anonymous set."

c. Withdrawal (Proof)

The user wants to withdraw funds to a new address.

She generates a zero-knowledge proof to prove to the contract: "I know the secret s corresponding to a commitment in the list, and I have not double spent."

At the same time, she publicly reveals the nullifier = Hash(s) (the same as the deposit receipt) to prevent double spending.

d. Verification and Issuance

The contract verifies the validity of the zero-knowledge proof and checks whether the nullifier has not been used.

After verification, the contract sends the funds to the new address specified by the user and marks the nullifier as used.

Ring Signatures

To address the issue of anonymity leakage, in 2001, Ronald Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Yael Tauman jointly proposed the concept of ring signatures. Over the following years, it rapidly developed, giving rise to various variants for different environments, such as linkable ring signatures, threshold ring signatures, and traceable ring signatures. Linkable ring signatures can prevent the same private key from signing multiple times within the ring, primarily used to prevent double spending in digital currencies like Monero. Traceable ring signatures can reveal the signer under specific conditions, mainly used in anonymous systems that require accountability. Threshold ring signatures require multiple parties to collaborate to generate a signature, mainly used in scenarios like anonymous collaborative authorization. Basic ring signatures can be categorized into two types based on their implementation: RSA and elliptic curves.

Below is a description of a typical elliptic curve-based ring signature scheme (SAG paradigm).

Key Image

The real signer (indexed as (s)) uses their private key (x_s) to compute the key image (I):

where (H_p(·)) is a hash function that maps the input to a point on the elliptic curve.

Initialization and Challenge Chain Start

The signer selects a random number (α) as a seed and computes the initial commitment:

where (H) is a hash function that outputs a scalar, and (G) is the generator of the elliptic curve.

Generate Responses for Other Members (Simulation)

For all positions (i ≠ s) (i.e., non-real signers), the signer randomly generates (r_i) and computes:

Generate Response for the Real Signer (Closing the Ring)

At the real signer's own position (s), they use their private key (xs) to compute the response (rs) to close the ring:

where (l) is the order of the elliptic curve group.

Verification Process

The verifier uses the (c1) and (ri) sequences from the signature to recompute for all (i = 1) to (n):

Finally, the verifier checks whether the ring is closed by verifying the following equation:

If the equation holds and the key image (I) has not been used, the signature is valid.

Specific Implementation

The most famous representative of mixers is Tornado Cash, while the most famous representative of ring signatures is Monero. Both possess strong anonymity; however, due to this, some regulatory agencies in certain countries have required cryptocurrency exchanges to delist Monero because it is difficult to comply with anti-money laundering regulations. In 2022, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control placed Tornado Cash's smart contract address on the sanctions list, citing its use in laundering hundreds of millions of dollars in hacker proceeds, leading to the shutdown of its GitHub repository and the arrest of its developers. Therefore, while mixers and ring signatures are powerful, their untraceable nature faces significant regulatory pressure and legal risks.

Trusted Execution Environment (TEE, Intel SGX)

A Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) is a core technology proposed to protect the secure operation of sensitive programs within computing devices. Its basic principle is to provide a secure execution environment for sensitive programs that is completely isolated from the general computing environment through strict isolation of hardware and software. The birth of TEE technology aims to address the fundamental security issues in traditional computing models, where the operating system or hypervisor, as the highest authority entity, may become a potential attack surface. The BenFen chain draws on the hardware isolation concept of TEE in privacy payments, generating encrypted transactions through off-chain MPC collaboration, only placing state changes on-chain, thus achieving isolation protection of sensitive data and avoiding direct exposure on-chain.

The core goals of TEE are to achieve data confidentiality, integrity, and the trustworthiness of the computation process. By utilizing the built-in hardware security features of processors, TEE can ensure that data remains encrypted in memory during code execution and can only be decrypted and processed within the TEE. This hardware-assisted isolation mechanism is the fundamental characteristic that distinguishes TEE from pure software sandbox environments, providing a more robust root of trust.

The core value of TEE lies in establishing a hardware-assisted trust boundary. Traditional software isolation mechanisms rely on the correctness of the operating system. Once the operating system kernel is compromised, all application data and code running on it will be exposed. However, TEE creates a "secure world" and a "normal world" within the CPU, allowing security-sensitive programs to run in the Secure World, even if the OS or Hypervisor in the Normal World is completely compromised, it cannot directly access or tamper with the data and execution processes in the Secure World.

The implementation of this isolation mechanism typically involves special memory management units, memory encryption engines, and specific CPU instruction sets. For example, Intel SGX ensures that data within the Enclave is always encrypted when it leaves the CPU boundary through encrypted page caching. This design significantly reduces the overall attack surface of the system by narrowing the trust boundary to the Enclave itself. Below is an analysis of mainstream TEE architectures:

ARM TrustZone (TZ) Architecture Analysis

ARM TrustZone is the most widely deployed TEE technology in mobile and embedded devices. It is based on the principle of hardware partitioning, dividing the SoC's hardware and software resources into two independent execution environments: the secure world and the normal world.

Core Principle: Hardware-level isolation is controlled by specific mode bits of the CPU. At system startup, it first enters the Secure World, managed by a secure operating system responsible for managing the TEE environment. The switching between the two worlds is managed by a secure monitor through specific SMC instructions.

Isolation Mechanism and Challenges: The isolation granularity of TrustZone is at the operating system level. This means that security-sensitive applications run on top of a complete secure operating system kernel. While this provides rich functionality, its security model relies on the integrity and vulnerability immunity of the secure operating system itself. The code volume of the secure operating system is much larger than that of Intel SGX's micro Enclave, making its attack surface relatively larger and requiring continuous auditing and maintenance.

Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX) Architecture Analysis

Intel SGX is a fine-grained TEE technology designed for data centers and desktop platforms. It narrows the protection granularity to the application level, allowing developers to encapsulate sensitive code and data within a protected memory area called an Enclave.

Core Principle: SGX achieves isolation through a special instruction set and memory encryption mechanism (EPC). Data in the EPC is encrypted by a memory encryption engine before leaving the CPU chip, preventing OS, Hypervisor, or even motherboard firmware from eavesdropping.

Isolation Mechanism and Challenges: The greatest advantage of SGX lies in its extremely small root of trust. The code inside the Enclave is the only trusted software. However, this deep integration into complex micro-architectures makes SGX a primary target for side-channel attacks. For example, SGX uses caching and paging mechanisms, and these shared resources become perfect channels for attackers to exploit timing differences to steal information. Its remote attestation mechanism is also relatively complex, relying on Intel's signature service to verify the authenticity and integrity of the Enclave.

Although TEE provides strong security guarantees through hardware isolation, its trust model is not flawless. Early TEE architecture designs focused on providing isolation mechanisms for memory and execution logic to resist direct eavesdropping and tampering from high-privilege software environments. However, with the advancement of processor technology and the increasing complexity of micro-architectures, research has found that the characteristic of TEE architecture "only providing isolation mechanisms" makes it ineffective against "software side-channel attacks" that exploit micro-architectural state leakage. Modern CPUs widely adopt shared resources in pursuit of extreme performance. These shared resources create unexpected communication channels between the secure world and the normal world. When sensitive programs execute within the TEE, their memory access patterns can cause measurable changes in the state of shared hardware resources. Attackers operating in the normal world can infer confidential information being processed inside the TEE, such as encryption keys or execution paths of sensitive algorithms, by measuring these changes in micro-architectural states.

There have been several significant TEE security vulnerabilities and attack cases in history; below are two selected for brief introduction:

- Foreshadow (L1TF) - Targeting Intel SGX

Time: Disclosed in 2018

Core Vulnerability: A flaw in the speculative execution mechanism of Intel CPUs, particularly the L1 terminal fault.

Attack Principle: By exploiting the CPU's speculative execution vulnerability, the attacker induces the CPU to load protected data from the enclave into the shared L1 cache of all programs before a fault occurs. The attacker can then probe this data through cache side-channel attacks, thereby stealing any secrets from the enclave, such as keys or passwords.

Severity: Extremely high. It can break SGX's core security promise, extracting arbitrary data from the enclave. Variants targeting the operating system kernel and hypervisor also exist.

- AEPIC Leap - Targeting Intel SGX

Time: Disclosed in 2022

Core Vulnerability: An extremely rare architectural flaw. The memory-mapped I/O of the CPU has a design defect that allows unmapped memory contents to be leaked through the CPU's prefetcher.

Attack Principle: The attacker can construct specific MMIO accesses that cause the CPU prefetcher to load private data from the enclave into the cache, allowing extraction through side channels. Its uniqueness lies in the fact that this is a verifiable architectural vulnerability that does not rely on timing measurements from side-channel analysis, theoretically offering higher reliability and accuracy.

Severity: Extremely high. It indicates that even if the microarchitecture is flawless, oversights in architectural design can lead to catastrophic data leaks.

Therefore, the biggest challenge for TEE technology is not achieving logical isolation but rather addressing the physical/timing shared channels introduced by CPU performance optimizations. This challenge forces security research to shift from purely isolation defenses to complex runtime integrity proofs and side-channel immunity designs.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is an effective method for addressing privacy and security issues. It is a powerful cryptographic tool whose core capability lies in allowing arbitrary homomorphic computations on encrypted data. This means that, theoretically, any complex algorithm can be executed on ciphertext or any computational circuit can be constructed without prior decryption. The FHE-MPC hybrid model adopted by the BenFen chain performs stateful computations at the underlying level, ensuring that data remains encrypted, which aligns with the core concept of FHE.

The development history of fully homomorphic encryption is a process of continuous optimization from theoretical breakthroughs to engineering practice. It began in 2009 with Gentry's first feasible scheme, but this scheme had only theoretical significance due to its extremely low computational efficiency. Subsequently, research quickly shifted to second and third-generation schemes based on lattice hard problems, particularly those relying on Learning With Errors (LWE) and Ring Learning With Errors (RLWE).

Definitions of Homomorphic Encryption (HE) and Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)

An encryption scheme E is called homomorphic encryption (HE) if it supports homomorphism for a specific operation ∘. Formally, if E(m1)·E(m2) = E(m1 ∘ m2) holds, then the scheme is said to have homomorphic properties.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is a more powerful structure that requires the encryption scheme to support two basic homomorphic operations simultaneously. In Boolean circuits, addition and multiplication are sufficient to construct any complex computational function, thus enabling arbitrary homomorphic computations on encrypted data. This capability gives FHE Turing completeness in computation.

Predecessor of FHE: Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE)

Before the advent of FHE, the cryptographic community had developed encryption schemes that support a single operation, known as Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE).

RSA Algorithm: RSA is one of the cornerstones of public-key cryptography. It possesses multiplicative homomorphism. Specifically, for ciphertext E(m1) and E(m2), their product, when decrypted in the ciphertext space, equals the plaintext product modulo N: E(m1)·E(m2) = E(m1·m2 (mod N)). However, RSA cannot perform addition on ciphertext.

Paillier Algorithm: The Paillier algorithm is another widely used PHE scheme that possesses additive homomorphism. The multiplication operation in the ciphertext space corresponds to addition in the plaintext space: E(m1)·E(m2) = E(m1 + m2 (mod N)). This scheme is very effective in scenarios such as secure voting systems, but it cannot perform multiplication on ciphertext.

Key Barrier: The Leap from Partially Homomorphic to Fully Homomorphic

The limitation of partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) schemes lies in their inability to support general computation. Computational circuits need to have both AND and XOR functionalities to achieve arbitrary logic. RSA and Paillier can only provide one of these, thus their application scope is strictly limited. More importantly, because PHE schemes often have a limited number of operations or only support a single operation, they are designed without needing to address the noise accumulation problem that arises during ciphertext operations.

The transition from PHE to FHE not only adds an operation but also crosses the threshold of Turing completeness. Once the requirement is to support arbitrary depth mixed addition and multiplication operations, the noise introduced by the encryption scheme to maintain security becomes a fatal flaw. This demand for complexity makes noise management mechanisms an indispensable core component of FHE architecture.

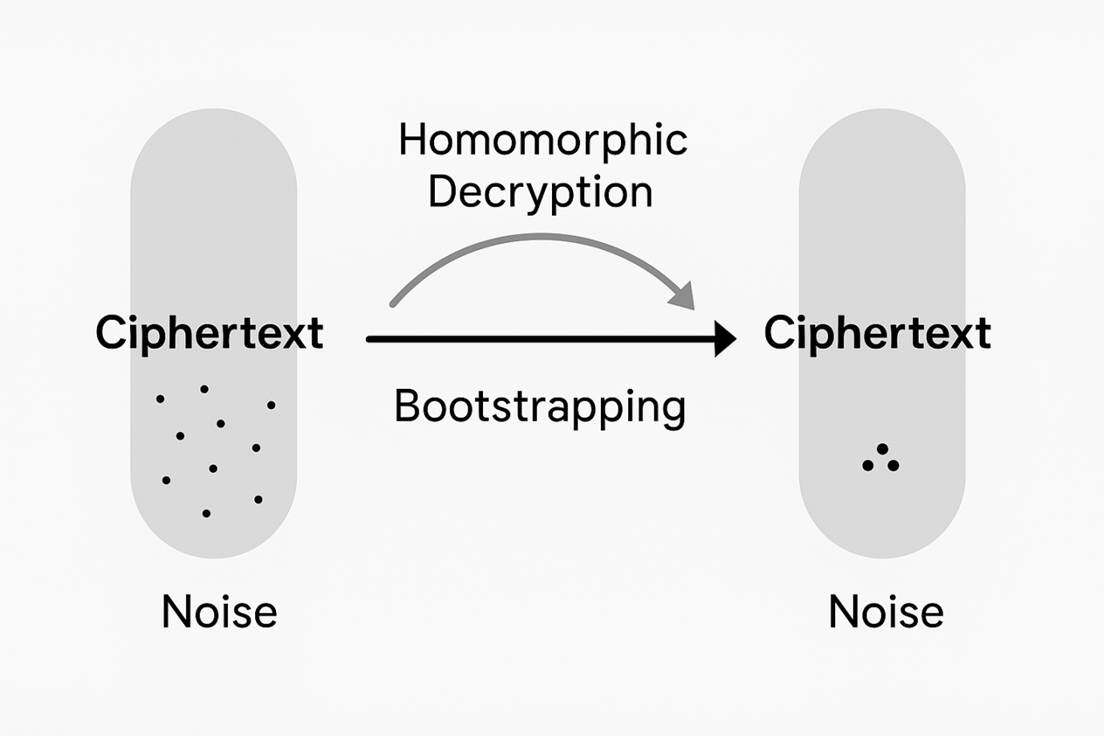

In 2009, Craig Gentry successfully constructed the first feasible fully homomorphic encryption scheme in history based on hard problems in ideal lattices. This was a milestone theoretical breakthrough, marking the transition of FHE from theoretical fantasy to practical possibility.

Gentry not only provided a specific scheme but also proposed a universal theoretical framework for constructing FHE schemes. The core idea of this framework is to decompose the construction of FHE into two steps: first, to construct a scheme that supports a limited number of homomorphic computations (SHE, Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption), and then to elevate the SHE scheme to support unlimited homomorphic operations through a bootstrapping mechanism.

In lattice-based encryption schemes, to achieve semantic security (i.e., the same plaintext can be encrypted into different ciphertexts), random noise must be introduced during the encryption process. The presence of noise is the foundation of the security of FHE schemes, but it is also the greatest obstacle to the functionality of FHE schemes. As homomorphic operations, especially homomorphic multiplication, continue, the noise in the ciphertext will accumulate and grow. Once the size of the noise exceeds the threshold set by the scheme parameters, the decryption process will fail to correctly recover the original plaintext, leading to decryption errors. Therefore, it is necessary to design an operation to effectively reduce the noise in ciphertext to ensure the correctness of computations.

Bootstrapping is the core technology in Gentry's framework for addressing the noise accumulation problem. The definition of the bootstrapping operation is: when homomorphic operations reach a point where the ciphertext noise is about to exceed the threshold and further computation cannot continue, the ciphertext undergoes its own homomorphic decryption operation. During the homomorphic decryption process, the private key itself needs to be encrypted. The result of bootstrapping is the generation of a new ciphertext that encrypts the same plaintext but with significantly reduced noise levels, thus allowing subsequent homomorphic operations to continue. Therefore, bootstrapping is considered the only current method for achieving fully homomorphic encryption and is a key and core technology in FHE schemes.

As the representative of the first generation of FHE, Gentry's scheme faces the challenge of how to enable the limited computational capability of the SHE scheme to homomorphically evaluate its own decryption circuit. Gentry successfully compressed the decryption circuit by utilizing sparse subsets and assumptions to preprocess the complex operations in the decryption circuit, allowing it to complete the decryption operation within the homomorphic computation depth it supports, thus achieving bootstrapping.

However, the implementation cost of the first generation of FHE is extremely high. Since it uses Boolean circuits to encrypt key information bit by bit, bootstrapping a single bit of information takes about 30 minutes. This enormous computational overhead made Gentry's scheme merely a theoretical proof of feasibility at the time, rather than a practical technology. The high computational cost became the main performance bottleneck for the industrial application of FHE algorithms.

Transition to Lattice Hard Problems LWE and RLWE

To overcome the inefficiency and complex Boolean circuit structure of the first-generation Gentry scheme based on ideal lattices, researchers began to seek more efficient algebraic structures and more manageable noise models. The second generation of FHE schemes shifted to using Learning With Errors (LWE) and its ring variant, Ring Learning With Errors (RLWE), as the security foundation.

This transition is a key engineering decision in the development of FHE. The structure provided by LWE/RLWE is more conducive to noise management, especially RLWE, which transforms complex matrix operations into faster polynomial operations, laying the groundwork for subsequent optimizations. The BGV (Brakerski-Gentry-Vaikuntanathan) and BFV (Brakerski/Fan-Vercauteren) schemes are typical representatives of this generation of schemes.

BGV and BFV: Levelled Homomorphic Encryption and Noise Management

The second generation of schemes introduced the concept of Levelled Homomorphic Encryption (LHE). LHE schemes pre-determine the maximum number of homomorphic multiplications (i.e., circuit depth) that the scheme can support during parameter settings.

The BGV scheme is one of the first compact FHE schemes based on LWE/RLWE. It introduces a dynamic noise management technique—modulus switching. The modulus switching mechanism does not rely entirely on the extremely costly bootstrapping operation; instead, it proportionally reduces the size of the noise relative to the modulus by decreasing the modulus of the ciphertext after each homomorphic multiplication. This effectively "buys" more computational levels. Only when all preset levels are exhausted and deeper computations are needed does it require a complete bootstrapping operation.

The BFV scheme is primarily used for precise integer arithmetic. Optimizations for BFV focus on reducing initial noise and optimizing the modulus switching process. For example, by precomputing ⌊tq⌋m → ⌊tqm⌋ to reduce initial noise. Another important optimization is to perform modulus switching after the relinearization operation, thereby reducing the dimensions required for modulus switching. Additionally, processing the BFV modulus in layers and switching to a smaller modulus after multiplication can slow down the noise growth rate.

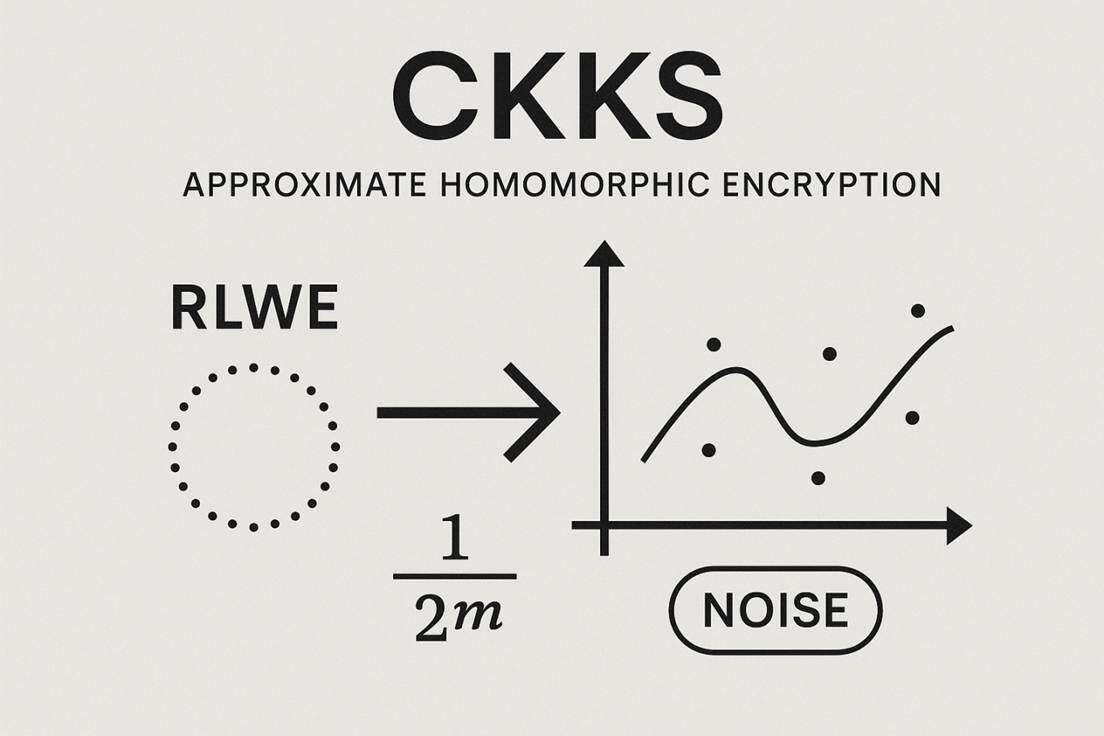

CKKS Class Schemes (Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song): Approximate Homomorphic Encryption

The CKKS scheme is specifically designed for homomorphic computations on real or complex numbers, supporting approximate calculations, which are crucial for statistical analysis, machine learning, and AI applications.

Core Assumption: The CKKS scheme is built on the algebraic structure of RLWE, thus it naturally supports SIMD parallel operations.

Noise Handling and Precision: CKKS is designed to allow for controllable errors, which are used to encode the precision of floating-point numbers. Therefore, the optimization focus of CKKS is on improving computational precision after bootstrapping. Researchers achieve precise modulus reduction operations by using different approximation functions. Depending on the technical route, the bootstrapping precision range of CKKS class schemes varies widely, from 24 bits to the current maximum of 255 bits.

FHE provides unique advantages in addressing modern data privacy challenges:

Data Sovereignty and Privacy Protection: The core value of FHE lies in its ability to perform computations on sensitive data in untrusted environments without exposing the data content to service providers. This greatly enhances the protection of data privacy and supports the separation of data ownership and control.

Support for Arbitrary Computation: FHE achieves Turing completeness for arbitrary complex functions by supporting both addition and multiplication as basic operations. This enables FHE to be applied in general scenarios such as complex machine learning model evaluation, genomics analysis, and financial modeling, which are beyond the reach of partially homomorphic encryption schemes.

Theoretical Quantum Resistance: Modern FHE schemes (based on LWE/RLWE) rely on hard problems in lattices. These problems are widely regarded in the cryptographic community as having the potential to resist quantum attacks, providing FHE with long-term security advantages that surpass traditional public key algorithms like RSA and ECC.

High Throughput (SIMD): Schemes that adopt the RLWE structure (such as BGV and CKKS) achieve SIMD operations through message packing techniques. This allows FHE to process data in batches, significantly compensating for the substantial performance overhead of single homomorphic operations and improving data processing throughput in practical applications.

Despite significant advancements in FHE, its industrial application still faces multiple challenges:

Computational Performance Bottleneck: Although the bootstrapping time has been reduced from 30 minutes to milliseconds since Gentry's scheme, the computational cost of homomorphic operations remains much higher compared to computations performed on plaintext. The computational cost of bootstrapping operations remains expensive, representing the primary performance bottleneck of current FHE algorithms.

Storage Overhead Due to Ciphertext Expansion: FHE ciphertexts are typically much larger than the original plaintext data. This ciphertext expansion leads to significant storage requirements and bandwidth consumption, increasing system complexity and operational costs. For example, LWE/RLWE ciphertexts require multiple high-dimensional polynomials to represent a plaintext in order to resist noise and support relinearization.

Complexity of Key Management: FHE requires managing complex key structures, particularly the evaluation keys needed for relinearization and bootstrapping, which are large in size and difficult to manage.

Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC)

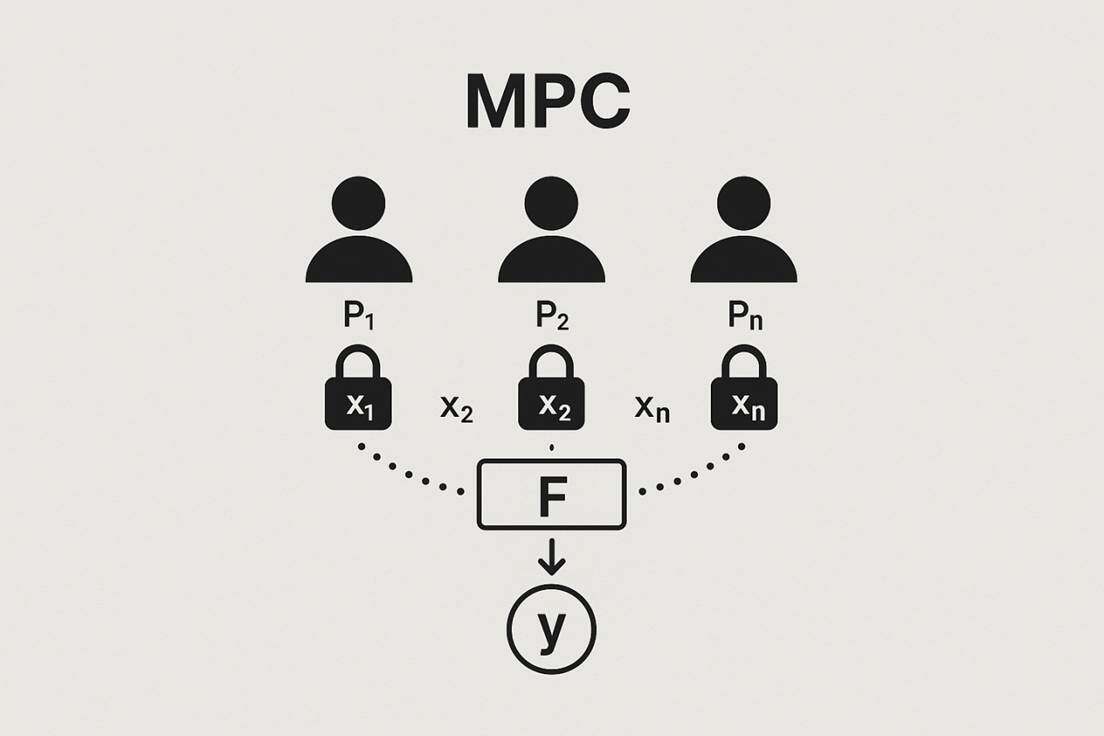

Core Paradigms and Mathematical Definitions of MPC

Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC) is one of the core research areas in cryptography, aimed at resolving the fundamental conflict between data privacy and collaborative computation. MPC allows n mutually distrustful participants P1, …, Pn to jointly compute a predefined function F(x1, …, xn) = y without revealing their private inputs x1, …, xn. This paradigm transforms the function into basic operational units that are easy to encrypt, enabling computations on ciphertext or shared data.

The security of MPC is primarily defined by two core properties: input privacy and result correctness. Input privacy requires that no participant or external attacker can learn any information about other parties' inputs from the execution of the protocol, except for the information contained in the computed result itself. Result correctness ensures that the output y of the protocol must accurately equal the computation result of function F on all inputs, preventing corrupt parties from affecting the validity of the output. Depending on the underlying cryptographic primitives, MPC protocols can be broadly classified into two categories: protocols based on Garbled Circuits (GC) and protocols based on Secret Sharing (SS).

Phased Division of Reports and Overview of Historical Milestones

The development of MPC is not linear but has undergone a transition from abstract mathematical concepts to practical engineering systems. This report divides the evolution of MPC into several key stages, aiming to precisely analyze the construction of its theoretical foundations, the upgrading of security standards, breakthroughs in engineering efficiency, and the eventual industrial implementation:

Theoretical Foundations and Feasibility Proofs: Establishing two foundational protocol paradigms for MPC.

Theoretical Deepening and Model Expansion: Introducing system-level security frameworks.

Efficiency Breakthroughs and Moving Beyond Pure Theory: Transitioning MPC from academic prototypes to engineering feasibility through algebraic optimization and hybrid protocols.

The BenFen privacy payment system embodies the industrial implementation of these stages, with its FAST MPC module initially implementing confidential transaction generation and verification entirely using MPC, while subsequent iterations plan to integrate protocols like FHE to provide more complex functionalities, such as improved MPC and advanced cryptographic fusion architectures, supporting second-level privacy confirmation and zero gas fee experiences.

Theoretical Foundations and Feasibility Proofs

The 1980s marked the beginning of MPC theory, with its core contribution being the proof of the feasibility of universal secure computation and the establishment of two fundamental protocol structures.

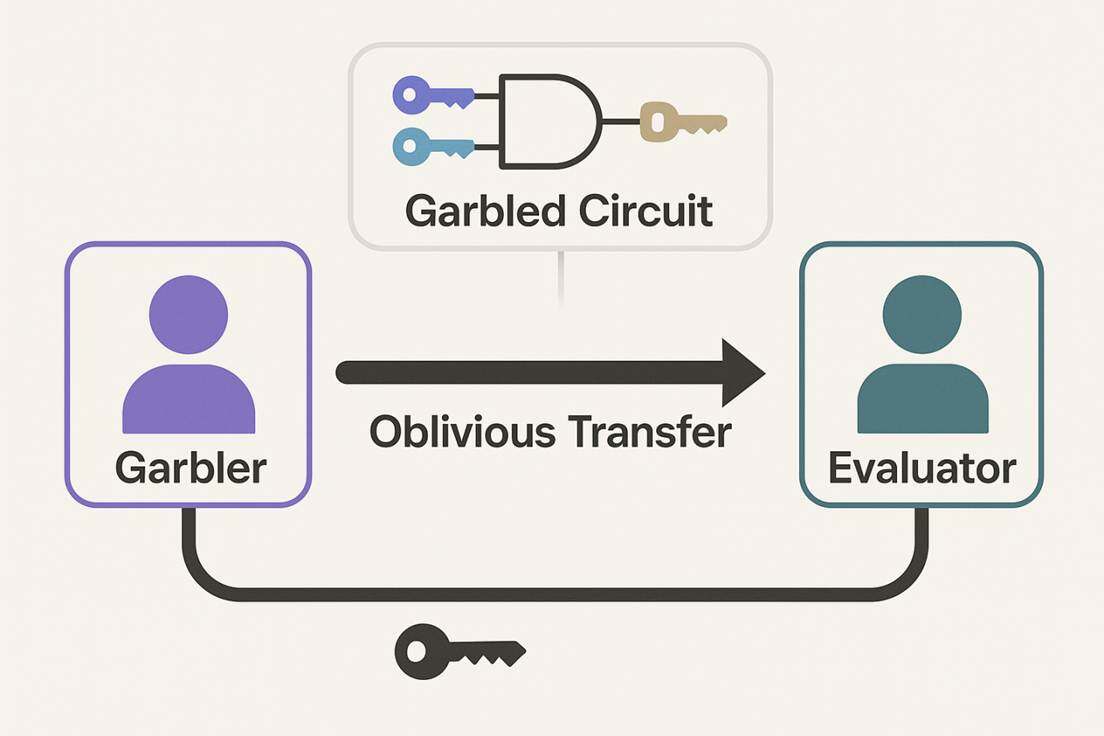

Yao’s Garbled Circuits (GC)

Yao's Garbled Circuits protocol is the most iconic technology in the field of secure computation. Although the initial concept of this technology can be traced back to Andrew Yao's "Millionaires' Problem" proposed in 1982, the complete protocol and its application details were mainly elaborated in subsequent research. The core of the GC protocol lies in bilateral computation, allowing two mutually distrustful parties to securely evaluate a function without a third party.

The mechanism of GC requires transforming any function to be computed into a Boolean circuit. There are two main roles in the protocol: the "Garbler" and the "Evaluator." The Garbler generates a garbled circuit, which contains encrypted gates that replace the truth table with encryption keys. The Evaluator receives the garbled circuit and securely obtains the key labels for its inputs through an Oblivious Transfer (OT) mechanism, then evaluates the circuit based on these keys. A significant advantage of the GC protocol is its constant round communication feature. Regardless of the depth or size of the Boolean circuit, the number of communication rounds is fixed. This is crucial for low-latency applications in wide-area network deployments, as it effectively avoids the costly overhead associated with network delays. However, the original GC protocol is inherently suited for bilateral computation, and extending it to multi-party scenarios requires the introduction of additional and complex mechanisms.

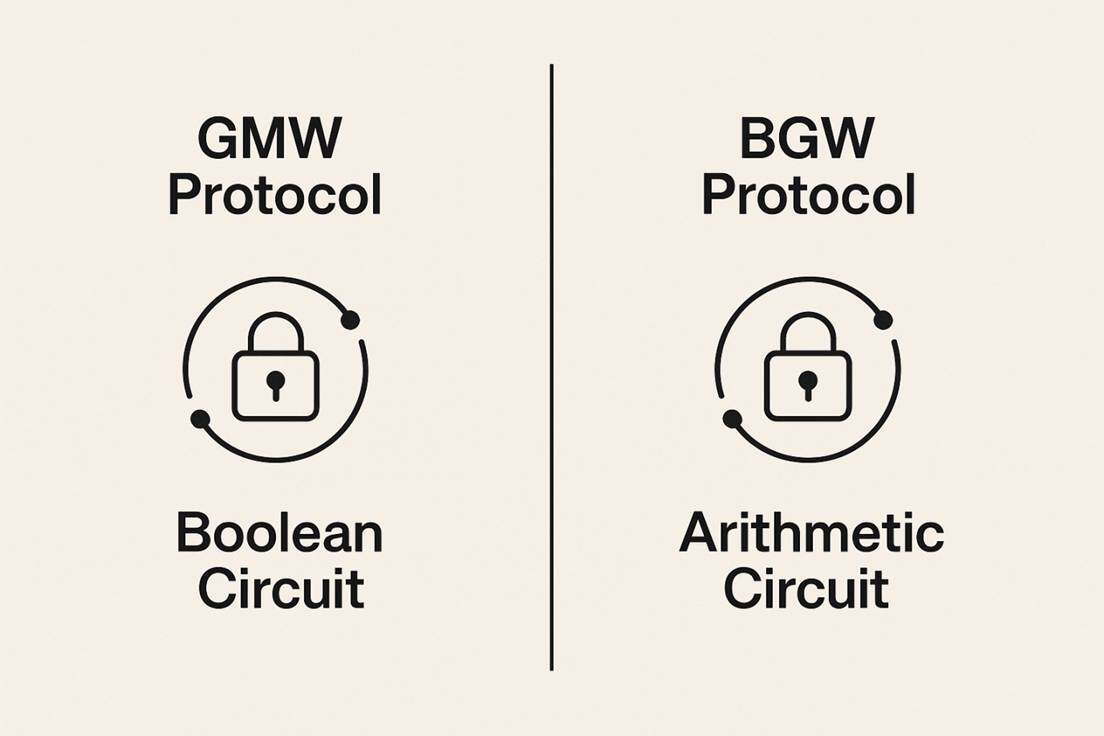

GMW Protocol and BGW Protocol

In contrast to the GC-based secure computation path, the GMW protocol proposed by Goldreich, Micali, and Wigderson in 1987 provides a path for universal multi-party computation based on secret sharing and information-theoretic security.

The GMW protocol operates on Boolean circuits, with its main mechanism relying on sharing inputs as secrets among all participants. Under the GMW protocol, if the number of corrupt parties t satisfies the honest majority condition, the protocol can achieve unconditional security, meaning information-theoretic security without relying on any computational complexity assumptions. This means that even if an attacker has unlimited computational power, they cannot learn the secret inputs from the shared information.

Alongside it is the BGW protocol (Ben-Or-Goldwasser-Wigderson), which is also based on secret sharing but primarily applies to arithmetic circuits rather than Boolean circuits. Unlike GC, the number of communication rounds in GMW and BGW protocols typically depends on the circuit depth of the function to be computed. This characteristic often results in poorer performance in environments with high network latency compared to the constant-round GC protocol.

The theoretical foundation stage of MPC established two independent security paradigms. The GC protocol provides a constant-round, computationally secure solution focused on optimizing low latency, while the GMW/BGW protocols offer information-theoretic security solutions dependent on circuit depth, emphasizing multi-party robustness. This bifurcation is theoretically necessary as it reveals the inherent contradiction between achieving constant rounds and multi-party information-theoretic security without sacrificing computational assumptions.

Although secret sharing itself is not a complete MPC protocol, it serves as a foundational toolbox for multi-party protocols like GMW/BGW, enabling secure function evaluation and resistance to malicious behavior. However, at this stage, the main challenge faced by MPC is the lack of a universal protocol that can simultaneously achieve high efficiency, multi-party support, information-theoretic security, and constant-round communication. The initial implementations of MPC faced significant communication overhead and complexity, limiting their application in practical scenarios.

Theoretical Deepening and Model Expansion

After the feasibility of MPC was proven, research focus shifted to how to define and ensure the security of protocols in complex, dynamic, and composite environments.

Universal Composability (UC) Framework

Around 2001, Ran Canetti proposed the Universal Composability (UC) framework to address security issues of protocols in traditional cryptographic models. Traditional security definitions often focus only on the "stand-alone" security of protocols, neglecting potential vulnerabilities that may arise when protocols are used in parallel or nested as subroutines with other protocols.

The core idea of the UC framework is to define the security of a protocol as its equivalence to an "ideal functionality." The ideal functionality is a theoretically abstract, perfectly secure entity that flawlessly performs the required computations and security guarantees. If a real protocol P cannot be distinguished from this ideal functionality F in any environment, then P is considered UC secure. The UC framework models protocols in the interactive Turing machine model, where these machines activate each other through reading and writing communication tapes, simulating communication and computation in a computational network.

The introduction of the UC framework significantly raised the design standards for cryptographic protocols, becoming the universal language for security analysis of modern cryptographic protocols. However, UC also quickly revealed theoretical limitations. Research under the UC model has shown that achieving UC secure multi-party computation in a "pure model" is impossible. This impossibility result forced researchers to turn to non-pure models, such as those relying on non-malleable commitments or other forms of common setup assumptions. This means that to achieve security in complex system-level environments, MPC protocols must rely on certain infrastructure presets rather than being completely isolated protocols. Additionally, the explicit modeling of asynchronous communication and network delays in the UC framework, such as revealing information leakage through delay mechanisms, has also indirectly driven the continuous optimization of constant-round protocols to improve tolerance to changes in network environments.

Efficiency Breakthroughs and Moving Beyond Pure Theory

MPC reached a critical turning point in the late 2000s, with a series of algorithmic and engineering improvements transforming it from an academic concept into an engineering feasible system.

Early General MPC System Implementation: Fairplay (2004)