Original Title: "A Comprehensive Interpretation of the Singapore Monetary Authority's RWA Issuance Guideline Framework! Detailed Explanation of Seventeen Token Cases! Can Hong Kong Copy the Homework?"

Written by: Spinach Spinach

Introduction

In November 2025, during Hong Kong FinTech Week, I participated as a guest in the Stablecoin and RWA Regulatory Forum hosted by The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The host asked me a question: "What do you think is the biggest challenge facing RWA right now?"

"The biggest challenge facing RWA is not a technical issue, but a regulatory and legal issue—we lack clear rules and a regulatory framework."

This answer is not just my personal observation, but a consensus reached after years of deep engagement in the RWA sector, communicating with countless project parties, investors, and lawyers.

This also reflects the true state of the RWA industry in 2025—it's not a lack of technology or funding, but a lack of a regulatory framework that everyone can understand, operate within, and that can truly be implemented.

Just when everyone was troubled by this issue, Singapore took action again.

On November 14, 2025, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) quietly released a 34-page document—the "Guidelines on Tokenization of Capital Market Products," which includes detailed case studies of 17 different types of tokens.

The last time Singapore influenced the entire Asian Web3 industry was in May this year with the DTSP new regulations—a "major cleanup" of non-compliant Web3 businesses.

This time, Singapore is providing a standard model for RWA regulation across Asia.

What does this mean? Singapore has not abandoned digital assets and blockchain; rather, it is undergoing a strategic transformation—shutting down speculative, high-risk Web3 businesses and opening up the compliant, economically valuable RWA sector.

In this article, Spinach will break down the core points of this guideline document and the 17 specific cases to help you understand Singapore's regulatory philosophy behind this guideline.

Table of Contents

Global RWA Regulatory Dilemma: How Regulatory Uncertainty Stifles Innovation

Singapore's Solution: Technology Neutrality Principle and Economic Substance Analysis

Core Concepts: CMPs, SFA, and Regulatory Philosophy

Judging Criteria: Penetrating from Form to Substance

- Detailed Explanation of Token Types Constituting CMPs

Equity Tokens: Digital Representation of Ownership

Bond Tokens: Four Structures and Regulatory Boundaries (Lending Type/Repurchase Type/Stabilized Type/Packaged Type)

CIS Unit Tokens: Compliance Path for Fund Tokenization

Derivative Tokens: Regulatory Qualitative Analysis of Synthetic Assets

- Boundaries of Tokens Not Constituting CMPs

Functional Tokens, Governance Tokens, and Meme Coins

Compliance Space for NFTs and Data Recording Tokens

Cross-Border Regulatory Coordination: Limitations of the Howey Test

- Three Major Regulatory Innovations and Industry Impact

Disclosure Requirements: From Financial Transparency to Technical Transparency

Definition of "Control": Regulatory Trigger Mechanism for Custodial Services

Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: Failure of Offshore Structures

- Conclusion: Certainty is the Soil for Innovation

1. Global RWA Regulatory Dilemma: How Regulatory Uncertainty Stifles Innovation

This issue is not just my concern.

Under the existing regulatory framework, RWA tokens face a fundamental dilemma: these tokens often cannot directly represent the assets themselves, and true ownership still relies on off-chain mechanisms, while the industry lacks a standardized issuance framework.

Want to tokenize a commercial property worth HKD 100 million? You cannot simply divide the ownership into 100 million tokens because local real estate registration systems do not recognize on-chain records. Want to tokenize Apple Inc. stock? You also cannot directly convert the shares registered on NASDAQ into on-chain tokens—Apple's shareholder register will not show an Ethereum address like "0x123…abc."

So what to do? The only way is to establish a Cayman SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle), find a way to put the asset into this SPV, and then issue tokens representing "claims against the SPV."

Investors are not buying the building itself or Apple’s stock itself, but rather a debt or equity interest in a Cayman shell company, which just happens to hold that building or those stocks.

This is the fundamental paradox of RWA:

"We use on-chain tokens to 'represent' off-chain assets, but the law only recognizes off-chain property registrations, contracts, and custodial agreements, which have no direct legal binding on on-chain assets, and we have to use a complex legal framework to circumvent the existing regulatory framework to issue so-called RWAs."

Once a dispute arises, investors' rights cannot be guaranteed, and the end result is that these RWA projects become "pointless endeavors"—spending a lot of legal costs to build complex structures, but investors are not interested, resulting in no liquidity; claiming "tokenization," but true rights still depend on the traditional off-chain legal system, and even free circulation needs to consider regulatory risks.

What truly stifles innovation is not regulation itself, but uncertainty. Only by providing a clear and definite regulatory framework, telling the industry "what can be done, what cannot be done, and how to comply," can the entire RWA sector potentially experience explosive growth.

And Singapore's release of this guideline is a direct response to this dilemma.

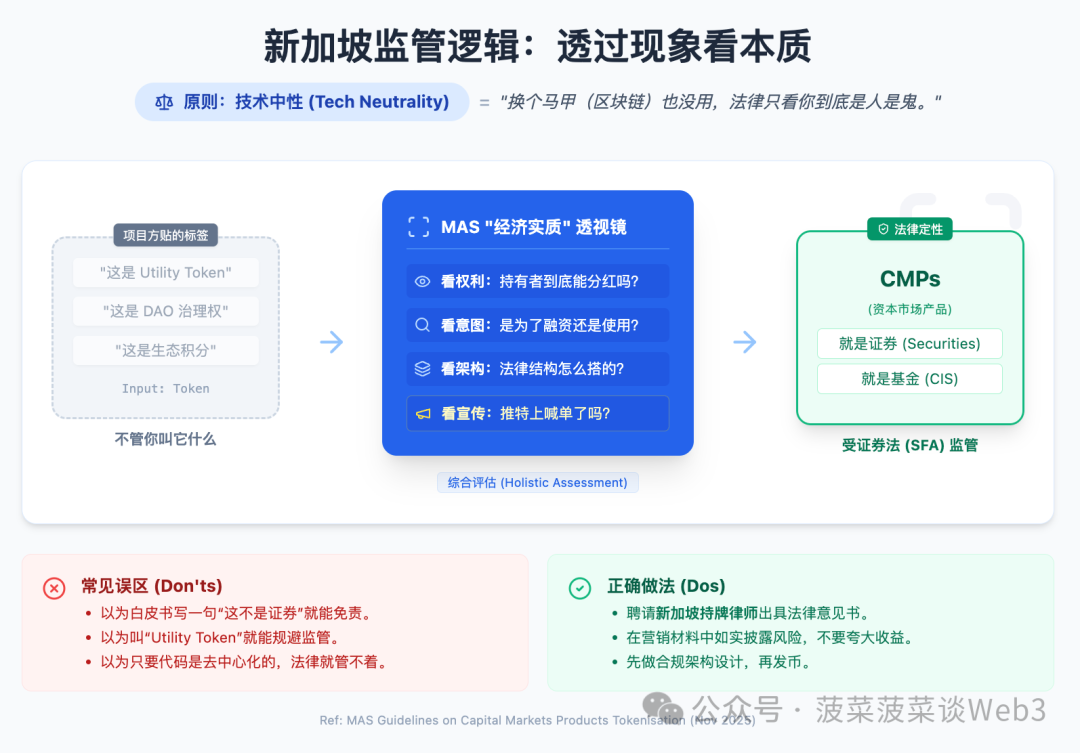

2. Singapore's Solution: Technology Neutrality Principle and Economic Substance Analysis

Core Concepts: CMPs, SFA, and Regulatory Philosophy

Before dissecting Singapore's guideline, we need to clarify a few basic concepts.

What are CMPs?

CMPs (Capital Markets Products) are financial investment products defined in Section 2(1) of Singapore's Securities and Futures Act (SFA), including:

Securities: Shares, bonds, business trust units, etc.

Units in a Collective Investment Scheme (CIS): Similar to fund shares

Derivatives Contracts: Including derivatives based on securities

Spot Foreign Exchange Contracts for Leveraged Trading

Other products specified by MAS

In simple terms, CMPs are financial investment products that need to be regulated under securities law within Singapore's regulatory framework. The core question of this guideline is: what kind of digital tokens will be considered CMPs?

MAS provides a very clear answer: it does not look at the technical form, but at the economic substance.

In the words of the guideline: "same activity, same risk, same regulatory outcome."

What does this mean?

Regardless of whether you use blockchain, smart contracts, or traditional databases, as long as the economic substance of the token constitutes securities/CIS units/derivatives, it must be regulated according to the corresponding rules. Tokenization does not change the legal nature; technological innovation does not equal regulatory exemption.

This "technology-neutral" regulatory philosophy is not new—similar principles have been emphasized by the U.S. SEC and the EU's ESMA. But Singapore's brilliance lies in that it not only states the principle but also provides detailed operational guidelines and 17 specific cases.

Judging Criteria: Penetrating from Form to Substance

So, how does MAS determine whether a token constitutes CMPs?

The guideline provides a clear analytical framework: a comprehensive, economic substance-based assessment must be conducted on the token.

Specifically, it needs to examine:

The characteristics of the token: What rights does the token confer to the holder?

The intent of the issuer: What is the purpose of issuing the token?

The structure of the overall arrangement: How is the legal framework designed?

The bundle of rights attached to the token: What specific rights can the holder obtain?

The key point is that MAS will penetrate the surface form of the token to see what its economic substance truly is.

You cannot evade regulation by simply changing a name or phrasing. If the economic substance of your token is equity, then it will be regulated as equity; if the substance is debt, then it will be regulated as bonds; if the substance is fund shares, then it will be regulated as CIS.

The guideline particularly emphasizes an important principle: the assessment must be based on all relevant materials, including legal documents, issuance documents, and marketing materials.

This means:

Saying "this is not a security" in the white paper is useless; the actual rights structure must be examined.

Promoting "investment returns" or "dividend income" during marketing, even if not written in legal documents, will still be considered.

Public statements and social media comments from the project party may also become judgment criteria.

Moreover, MAS clearly states: it does not use industry terms like "utility token," "security token," or "native token" for classification.

Why? Because these labels are inherently vague and can be misused. MAS's attitude is very clear: no word games; I only look at economic substance.

Finally, the guideline includes a very practical reminder: all entities must obtain independent legal opinions from qualified lawyers in Singapore.

In other words, do not guess blindly, and do not take the project party's word for it. Want to issue tokens in Singapore? First, find a reliable Singapore lawyer to conduct compliance analysis based on MAS's framework.

This analytical framework may seem simple, but it addresses the most troublesome issue in the RWA industry: it provides a clear, actionable judgment standard.

No longer are there ambiguous answers like "maybe" or "needs specific analysis," but rather "based on these factors, following this logic, we arrive at this conclusion."

Next, let's see how MAS applies this framework to the 17 specific cases.

3. Detailed Explanation of Token Types Constituting CMPs

MAS provides 9 cases of "constituting CMPs" in the guideline, covering four major types: equity tokens, bond tokens, CIS unit tokens, and derivative tokens.

This section is the core of the entire guideline and contains the most practical value for RWA project parties.

Equity Tokens: Digital Representation of Ownership

Case 1: Tokens Representing Company Ownership

Imagine Company A is a real estate developer that wants to raise funds for a new shopping center project by issuing Token A. Token A is designed as a "digital form representing shares of Company A," granting holders corresponding ownership, dividend rights, and voting rights.

MAS's determination is very straightforward: Token A is a share and must operate according to all regulations regarding share issuance in the Securities and Futures Act.

This means:

A prospectus must be prepared and registered with MAS.

A "securities trading" license under the Capital Markets Services License is required.

Compliance with anti-money laundering/anti-terrorism financing (AML/CFT) requirements is necessary.

If investment advice is to be provided to investors, a financial adviser license is also required.

Of course, if certain conditions are met, the prospectus requirement can be waived:

Small offerings: Raising no more than SGD 5 million (approximately RMB 26 million) within 12 months.

Private placements: Selling to no more than 50 people within 12 months.

Sales only to institutional investors.

Sales only to accredited investors.

However, even if the prospectus requirement is waived, other regulatory requirements (licenses, AML/CFT, etc.) still apply.

This case seems simple, but MAS emphasizes a key question: how to determine if a token "constitutes or represents" shares?

The answer lies in three factors:

Ownership interest in a corporation: Does the token represent ownership in the company?

Liability of the token holder: Does the holder bear shareholder responsibilities?

Mutual covenants inter se: Is there a shareholder relationship among the holders?

If your token involves all three factors, then it is a share and cannot escape securities law regulation.

But if your token only grants holders a "voting right in company governance" without involving share transfer, dividends, or liquidation rights, it may not be considered a share—this leaves operational space for "governance tokens."

Bond Tokens: Four Structures and Regulatory Boundaries

Bond tokens are one of the most common structures in the RWA field and also the area with the most regulatory divergence. MAS provided four cases this time, covering almost all mainstream bond token designs.

Case 2: Lending-Based Tokens (Lending Type)

Company B has built a "decentralized lending platform," but the actual operation is as follows:

Establish an SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) for each startup.

Investors provide loans to the SPV.

The SPV issues Token B as proof of the loan.

Token B can be traded on Company B's platform in the secondary market.

MAS's determination: Token B is a bond. Because it "constitutes or proves the issuer's (SPV) debt to the token holders."

The brilliance of this case lies in its ability to shatter many project parties' illusions—one cannot evade securities law regulation through a "decentralized" narrative. As long as the economic substance is a debt relationship, no matter how many SPVs you use or how complex the smart contracts are, it does not change the fact that Token B is a bond.

Moreover, MAS specifically pointed out that Company B's platform may constitute an "organized market," requiring application to become an approved exchange or recognized market operator.

This means that if you want to create a "tokenized bond secondary trading platform," not only must the issuer comply, but the platform operator must also obtain a license.

Case 3: Platform Tokens with Buyback Clauses (Repurchase Type)

Company C developed a "diamond tokenization platform" and issued Token C to raise funds. The characteristics of Token C are:

Holders have the right to use the platform.

Holders can sell Token C back to Company C at a fixed price at any time.

Besides the platform usage right and buyback right, there are no other rights.

This design is quite cunning—on the surface, Token C is merely a "platform usage certificate," not involving equity or debt.

But MAS's determination left many project parties in a cold sweat: if Token C represents Company C's obligation to repay a certain amount to the holders, it may constitute a bond.

The key lies in the "buyback clause." If the company promises to "buy back at a fixed price at any time," this essentially constitutes a "commitment to future payment," aligning with the legal definition of a bond.

The impact of this case on the industry is profound—many project parties are accustomed to writing "buyback mechanisms" or "redemption mechanisms" in their white papers to enhance token attractiveness, but this may precisely turn the token from a "utility token" into a "security token."

Case 4: Regulatory Boundaries of Stablecoins (Stablecoin)

Company D issued Token D, pegged at 1 USD per token, aiming to maintain a 1:1 link with the US dollar. The implementation method is:

Only accepting USD electronic deposits to purchase Token D.

These deposits serve as "reserves" supporting the value of Token D.

Holders can exchange Token D for 1 USD at any time with Company D.

Isn't this the model of USDC/USDT?

MAS's determination is very nuanced: Token D may constitute a bond because Company D has the obligation to buy back the token at the price of 1 USD/Token D.

However, the guideline immediately adds a crucial caveat: if Token D falls under the definition of "e-money" in the Payment Services Act, MAS's general regulatory stance is not to regulate Token D as a bond.

This statement carries significant implications. It means:

The regulatory classification of stablecoins depends on the specific design: if primarily used for payments, it falls under the PS Act; if primarily for investment, it falls under the SFA.

The "payment function" is the key to distinguishing regulatory tracks: if your stablecoin is intended for daily payments in collaboration with retailers, it may not be considered a security; if it is merely transferring value between exchanges, it is likely to be considered a bond.

Regulatory arbitrage space still exists, but the boundaries are becoming clearer.

Case 5: Packaging Structure of Tokenized Bonds (Packaged Type)

Company E has created a more complex design:

Establish a trust, with Company E as the trustee.

The trust purchases bonds issued by Company F.

Issue Token E, granting holders cash flows generated from the trust assets (i.e., Company F's bonds).

However, the debt obligation of the holders is to Company E, not Company F.

This "packaging structure" is common in traditional finance (e.g., CDOs, CLOs), but how does it change in terms of regulatory nature after tokenization?

MAS's determination is very precise: Token E is a bond issued by Company E, distinct from Company F's bonds as two independent financial products.

This means:

Company E needs to prepare a separate prospectus.

Company E's information disclosure requirements are independent of Company F.

Investors need to assess the credit risks of both Company E and Company F.

The lesson from this case is: do not attempt to evade regulation through "packaging"—regulators will penetrate to see the substance.

CIS Unit Tokens: Compliance Path for Fund Tokenization

CIS (Collective Investment Scheme) is the legal term for "funds" in Singapore. In simple terms, it refers to arrangements where "investors' money is pooled together and managed by professionals, with returns distributed according to shares."

Case 6: Standard Tokenized Fund

Company G issued Token G, with funds used to invest in equity of fintech startups, mining equipment, and real estate. Company G is responsible for portfolio management, and holders have no rights to participate in daily decision-making, with profits distributed according to their holdings.

MAS's determination: Company G's arrangement constitutes a CIS, and Token G is a CIS unit.

This means:

A prospectus is required (unless exempt).

The CIS itself needs authorization or recognition.

Compliance with investment restrictions is necessary (e.g., cannot invest more than 10% of assets in a single entity).

Compliance with the Code on Collective Investment Schemes is required.

Company G must hold a fund management license.

The greatest significance of this case is that it clarifies that "tokenized funds" are not something new—if you are pooling investors' money, managing it, and sharing returns, it is a fund, and tokenization does not change this essence.

Case 7: Physical Asset-Backed Token Fund

Company H's design is even more misleading:

Issue Token H, raising funds to purchase physical gold.

The gold is held in trust by Company H for the holders.

Holders have no right to physical delivery of the gold.

Holders gain returns from the increase in gold prices through trading Token H.

Company H's marketing pitch is: "Token H does not represent any rights or value; it is merely a digital collectible."

But MAS's determination is incisive: no matter how you promote it, the economic substance of Token H is "representing a portion of rights in a gold investment portfolio," thus it is a CIS unit.

This case has shocked many project parties involved in NFTs and commodity tokens—one cannot change the legal nature of a token by "rephrasing." If investors buy your token primarily for the returns from rising gold prices, rather than for holding the "digital collectible" itself, it constitutes an investment contract, and it cannot escape securities law regulation.

Case 8: Regulatory Blind Spot for Offshore Funds

Company I is registered in Singapore, but Token I is only sold to overseas investors and not open to Singaporeans.

Can this "offshore structure" evade Singapore's regulation?

MAS's answer is: partially yes. Specifically:

Since Token I is not sold to Singaporeans, Part 13 of the SFA (regarding issuance and fundraising) does not apply.

However, if Company I operates fund management business in Singapore (e.g., the portfolio management team is in Singapore), it still needs to hold a fund management license.

The lesson from this case is: the standard for determining jurisdiction is "where the activity occurs" rather than "where the investors are located." You cannot assume that just because you are only raising funds from overseas, you can operate fund management business in Singapore without a license.

Derivative Tokens: Regulatory Qualitative Analysis of Synthetic Assets

Derivative tokens are the most technically complex and also the area most prone to pitfalls.

Case 9: Price Reference Tokens

Company J issued Token J, which references the stock price of Singapore-listed Company Z. Investors can bet on the rise and fall of Company Z's stock price through Token J without actually holding shares of Company Z. Company J promises to buy back Token J at a future date at a price referencing Company Z's stock price.

MAS's determination: Token J is a securities-based derivatives contract.

The logical chain for this determination is:

The value of Token J references the value of another security (Company Z's stock)—consistent with the definition of "derivative."

Company J has an obligation to fulfill the buyback obligation at a future date—consistent with the definition of "contract."

The underlying asset is a security—therefore, it is a "securities-based derivative."

This means that Company J not only needs a prospectus but may also require a derivatives trading license (dealing in derivatives).

This case has a significant impact on "synthetic assets" project parties. There are many "on-chain stocks" and "on-chain commodities" projects in the market, which essentially allow users to gain exposure to price changes of the underlying assets through tokens. Singapore's stance is very clear: these are all derivatives and must be regulated as such.

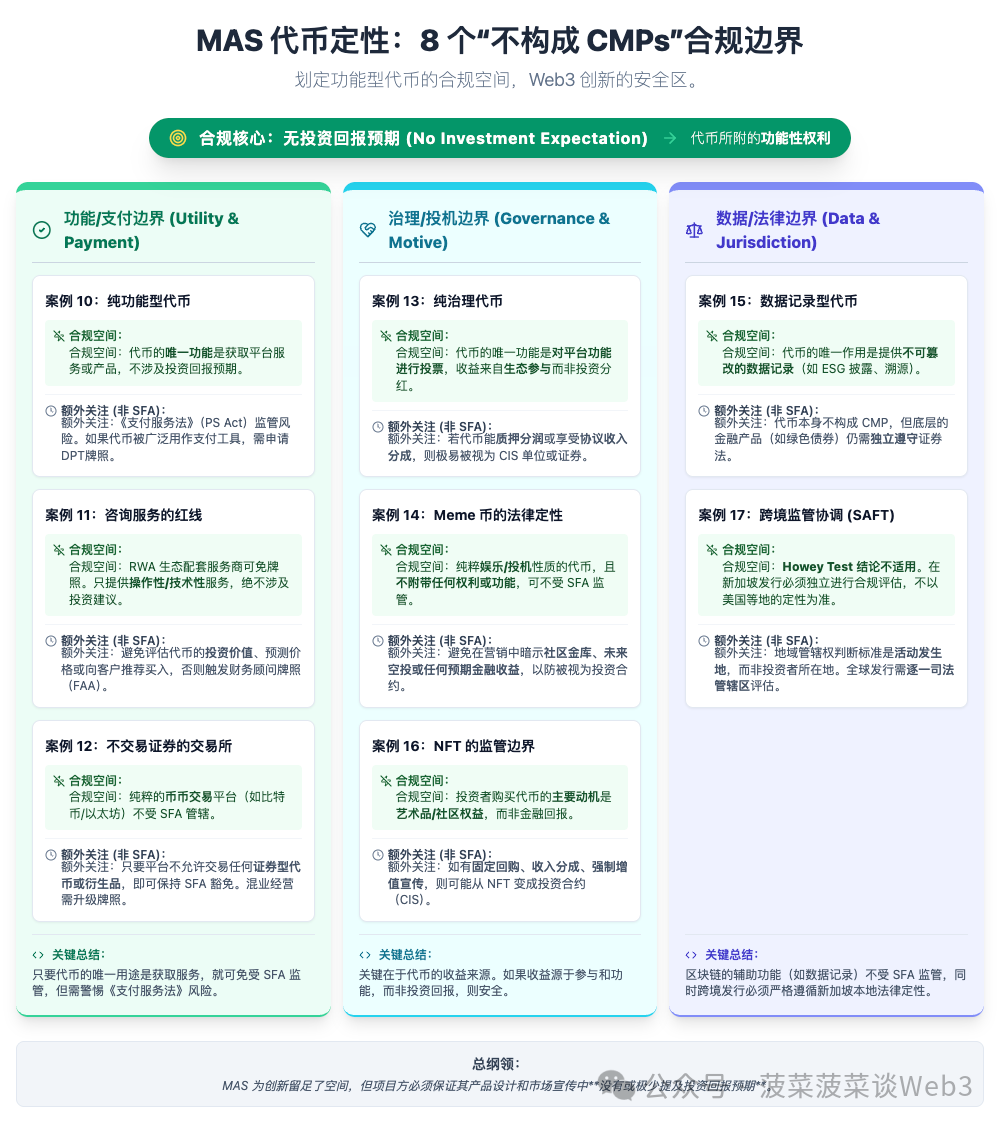

IV. Boundaries of Tokens That Do Not Constitute CMPs

After discussing "what needs to be regulated," let's look at "what does not need to be regulated." This part is equally important as it delineates the compliance boundaries for "utility tokens."

MAS provided eight cases of "not constituting CMPs" in the guidelines, leaving clear operational space for Web3 innovation.

Utility Tokens, Governance Tokens, and Meme Coins

Case 10: Pure Utility Tokens

Company K developed a "computing power sharing platform" and issued Token K for payments within the platform. The sole function of Token K is to "rent computing power provided by other users," with no financial attributes such as investment, dividends, or buybacks.

MAS's determination: Token K is not a CMP and is not subject to SFA or FAA regulation.

However, the guideline immediately adds: "Company K should separately assess whether its activities are regulated under the PS Act (Payment Services Act)."

The implication of this statement is that escaping securities law does not mean escaping other regulations. If Token K is widely used for payments, it may need to apply for a "digital payment token service" license.

This case establishes a clear boundary for purely utility tokens: as long as the sole purpose of the token is to obtain a service or product and does not involve expectations of investment returns, it can be exempt from securities law regulation.

Case 11: Red Line for Consulting Services

Company L provides comprehensive consulting services for clients wishing to issue tokens: reviewing white papers, introducing lawyers and developers, designing token economic models, etc. However, Company L has strict client selection criteria—only serving projects that issue "pure utility tokens," explicitly excluding any tokens with investment attributes.

Moreover, Company L does not provide legal opinions, does not comment on investment risks, and does not recommend "which token to buy"—its services are purely "operational," such as wallet creation and token transfer training.

MAS's determination: Company L's activities do not constitute regulated activities of "providing advice on company finances" nor do they constitute "financial advisory services," thus no license is required.

The takeaway from this case is that "support service providers" (technology development, marketing consulting, community operations, etc.) in the RWA ecosystem can operate relatively freely as long as they do not cross the red line of "investment advice."

But where is the boundary? Once you start assessing the "investment value" of tokens, predicting price trends, or recommending investors to buy, you have crossed the line.

Case 12: Exchanges Not Trading Securities

Company M operates a digital asset exchange, but the platform is configured to "only allow trading of digital payment tokens that do not constitute securities (such as Bitcoin), prohibiting the trading of any tokens that constitute securities/derivatives/CIS units."

MAS's determination: During the ban, the SFA does not apply to Company M.

However, the guideline warns: if Company M lifts the ban in the future and allows trading of securities tokens, it will need to apply to become an approved exchange or recognized market operator.

The practical significance of this case is that pure "crypto-to-crypto trading" platforms and "securities token trading" platforms are distinctly regulated tracks in Singapore. The former follows the PS Act, while the latter follows the SFA, and they cannot be conflated.

This also explains why the new DTSP regulations in May of this year had a significant impact on many exchanges—if you only trade non-security tokens like Bitcoin and Ethereum, although you need a DTSP license, the regulatory intensity is relatively low; however, if you want to list tokenized stocks, bonds, or funds, that is a completely different level of regulation.

Case 13: Subtle Boundaries of Governance Tokens

Company N built a "decentralized data platform" and issued Token N for fundraising. Token N only grants holders "voting rights on platform functions," with no dividends, buybacks, or other financial rights.

Company N also designed a "participation reward mechanism": users earn additional Token N based on their activities on the platform (such as participating in surveys, providing data), with the reward amount linked to user participation and unrelated to further investment.

MAS's determination: Token N is not a CMP.

The reasons are:

Token N does not represent any ownership in the company (not a share).

Token N does not reflect the issuer's debt (not a bond).

The reward mechanism is based on "user participation" rather than "investment returns," and does not involve the CIS logic of "pooling funds and sharing profits."

This case leaves operational space for "DAO governance tokens"—as long as the main function of the token is governance rights (voting rights), and the holders' benefits come from ecosystem participation rather than investment returns, it may not be considered a security.

But the devil is in the details. If your "governance token" can also:

Be staked to earn protocol revenue sharing.

Enjoy value appreciation from platform fee buybacks and burns.

Participate in the distribution of protocol treasury assets.

Then it becomes difficult to clarify whether it constitutes a CIS unit or a security.

Case 14: Legal Qualification of Meme Coins

Ms. O is a social media influencer who created and issued Token O based on a popular meme. Token O does not provide any rights and is purely "entertainment-oriented," with its value driven by market supply and demand and speculation. It has no intrinsic utility or function and is not a payment tool.

MAS's determination: Token O is neither a CMP nor an investment product, and neither the SFA nor the FAA applies.

However, the guideline adds: "Ms. O should separately assess whether her activities are regulated under the PS Act."

The interesting aspect of this case is that it acknowledges the existence of "purely speculative tokens" and considers that such tokens can be exempt from securities law regulation—provided they truly have no rights or functions.

But in practice, how many meme coins are truly "purely entertainment"? Many meme coin project parties will imply expectations of "community treasury," "future airdrops," "ecosystem development," etc., making it difficult to argue that it does not constitute an investment contract.

Compliance Space for NFTs and Data Recording Tokens

Case 15: Data Recording Tokens

Company P issued Token P to record the environmental impact data of its green bonds. The sole function of Token P is to "provide immutable data records," with no transfer of rights involved and not used for the ownership registration or transfer of the bonds.

MAS's determination: Token P is not a CMP.

However, the guideline emphasizes: the green bonds issued by Company P are still CMPs and must comply with securities law.

The significance of this case is that it leaves space for "blockchain-assisted disclosure"—you can use tokens to enhance information transparency as long as it is not linked to financial rights.

This has important implications for ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) disclosures, supply chain traceability, and other application scenarios: using blockchain to record data itself is not subject to securities law regulation, but the underlying financial products must still be regulated as they are.

Case 16: Regulatory Boundaries of NFTs

Company Q issued Token Q, with each token representing a unique digital artwork, and ownership proof stored on the blockchain. Holders cannot sell Token Q back to Company Q but can trade it on the secondary market. Company Q does not promote "investment returns," but holders enjoy limited intellectual property rights to the underlying artwork, as well as community membership rights. Company Q charges royalties on each secondary transaction.

MAS's determination: Token Q is not a CMP.

The reason is: the holders' rights are primarily "intellectual property + community rights," rather than financial returns.

However, the most valuable aspect of this case lies not in the conclusion but in the implicit warning: if Company Q emphasizes in its marketing that "Token Q's price will definitely rise," "buying will yield profits," or designs mechanisms for "staking to earn platform revenue sharing," then Token Q may transform from an NFT into an investment contract.

The key judgment criterion is: what is the primary motivation for investors to purchase the token—whether it is to enjoy the artwork/community rights themselves or to obtain financial returns.

Cross-Border Regulatory Coordination: Limitations of the Howey Test

Case 17: The Inapplicability of the US SAFT Model in Singapore

Company R is registered in the United States and issued Token R using the SAFT (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens) structure. According to the Howey Test under US law, Token R is determined to be an "investment contract" and therefore a security. Token R can be traded over-the-counter or on third-party exchanges.

Company R intends to offer Token R to global investors (including those in Singapore).

MAS's determination is very critical: the conclusion of the Howey Test is not the basis for Singapore's determination of whether a token is a CMP. Company R must separately assess the nature of Token R under Singapore's securities law.

This case breaks a common misconception—you cannot assume that just because it is deemed a security by the SEC in the US, it will also be a security in Singapore; and vice versa.

The legal definitions and regulatory standards differ from country to country, and cross-border issuance must undergo compliance assessments in each jurisdiction.

The implication for global RWA projects is: do not expect "one legal framework to rule them all." If you intend to raise funds from investors in multiple jurisdictions, you must conduct separate compliance analyses and may need to adopt different issuance structures in different regions.

This is also why the legal costs for many large RWA projects are so high—not because compliance is difficult in a single jurisdiction, but because they must simultaneously meet the requirements of multiple jurisdictions.

V. Three Major Regulatory Innovations and Industry Impact

After reading the 17 cases, we can extract three major innovations from Singapore's guidelines. These innovations are not only significant for Singapore but may also become reference standards for global RWA regulation.

Disclosure Requirements: From Financial Transparency to Technical Transparency

The prospectus for traditional financial products discloses information such as "financial status, business risks, and legal disputes." However, tokenized products add a layer of "technical risk"—smart contracts may have bugs, private keys may be lost, and DLT networks may be attacked.

MAS has specifically outlined a disclosure framework for "tokenization-specific risks" (see Section 3.7 of the guidelines), requiring issuers to disclose:

Technical Characteristics:

Type of DLT (public chain/private chain, permissioned/permissionless)

Network/application security measures (authentication, access management)

Use of smart contracts and governance mechanisms (whether audited before deployment)

Specific processes for token minting, issuance, transfer, redemption, and destruction

Key intermediary institutions and their roles (e.g., DLT network operators)

Rights Ownership:

Bundle of rights attached to or derived from the token

Whether the token confers legal ownership or beneficial ownership of CMP

How ownership is recorded (on-chain/off-chain)

Which record serves as legal proof of ownership when multiple records exist

Whether the issuer/relevant entities have the right to modify or override DLT records

Applicable legal and regulatory frameworks

Qualitative assessment under applicable laws (e.g., regulated as bonds under SFA)

Custodial Arrangements:

Custody methods (self-custody by investors, custody by issuer, third-party custody)

Private key management processes

If held by the issuer or affiliated company: processes to ensure investor assets are identifiable and independently maintained

For asset-backed tokens: custodial arrangements for underlying assets

Risk Disclosure:

Technical and Network Risks: DLT network/smart contract failures (coding errors, connectivity issues), security vulnerabilities (network attacks, smart contract flaws), unique risks of public permissionless blockchains (forks, 51% attacks)

Operational Risks: Arrangements with third-party service providers (DLT infrastructure, tokenization services), failure risks (unexpected interruptions, slow response times)

Legal and Regulatory Risks: Impact of current/future legal frameworks on issuance, trading, and redemption, legal status uncertainties (e.g., status under property law), legal/regulatory uncertainties or value risks arising from reforms

Custodial Risks: Loss/theft of private keys and their impact on investors, custodial risks of supporting assets and their impact on investors

Other Risks: Pricing/liquidity risks due to lack of an active trading market

The value of this disclosure framework lies in its transformation of "tokenization" from an abstract concept into a concrete compliance checklist.

Issuers can no longer use vague terms like "based on blockchain" to mislead investors; they must clearly explain the underlying technical architecture, rights ownership, and risk points one by one.

More importantly, this framework directly addresses the issue of "on-chain and off-chain disconnection"—MAS requires issuers to explicitly disclose: how ownership is recorded (on-chain or off-chain), what legal framework applies, and how the token is characterized under that legal framework.

This effectively forces issuers to clarify to investors: what do your rights actually depend on, is it on-chain records or off-chain legal documents.

This is of great significance for investor protection. At the very least, investors know what their rights depend on and where the risks lie before purchasing tokens.

Definition of "Control": Regulatory Trigger Mechanism for Custodial Services

In traditional finance, the definition of "custody" is straightforward—who physically holds the asset is the custodian.

However, in the token world, "holding" is a vague concept. If the token is on-chain, does the person holding the private key own the token, or does the "legal owner" of the address corresponding to the private key own the token? If it is a multi-signature wallet, does each signer count as a "custodian"?

MAS provides a very precise definition (see Section 4.6 of the guidelines): "Control" refers to "the ability to control access to the token or execute transactions involving the token."

The key points are:

Control does not need to be "exclusive"—even if you only hold one private key (or a fragment of a private key) for a multi-signature wallet, as long as your signature is necessary for the transaction, you have "control" over the token.

Control includes "indirect control"—if you maintain control over the private key through a third party (such as a custodian), that also counts.

The legal consequence of control is "the need for a custody license"—whether you are an exchange, wallet service provider, or DeFi protocol, as long as you have control over users' tokens, you may need to apply for a "providing custodial services" license under the Capital Markets Services License.

The impact of this definition on the industry is enormous.

Many DeFi protocols claim to be "non-custodial," arguing that "users hold their own private keys." However, if the protocol's smart contract has an "admin private key" that can freeze assets or upgrade contracts, then according to Singapore's standards, the protocol party has "control" over user assets and may need a custody license.

Many wallet service providers offer "MPC wallets" (multi-party computation wallets), where the private key is split into multiple fragments, with users holding one fragment and the service provider holding another. According to MAS's definition, the service provider clearly needs a custody license—because the fragment it holds is a necessary condition for completing transactions, which constitutes "control."

The brilliance of this definition lies in its focus on "who can influence the transfer of tokens" rather than getting bogged down in the technical detail of "who physically holds the private key."

Extrajudicial Jurisdiction: The Ineffectiveness of Offshore Structures

Singapore is a small country, but Section 339 of the SFA grants MAS powerful extraterritorial jurisdiction (see Section 5 of the guidelines): as long as activities "partially occur in Singapore," or "occur outside Singapore but have a substantial and reasonably foreseeable impact on Singapore," the SFA can apply.

What does this mean?

Suppose you are a Cayman-registered company, with a team in Hong Kong, selling tokenized US Treasury bonds to global investors (including those in Singapore). You might think, "I'm not operating in Singapore, why should I be subject to Singaporean regulation?"

But if:

Your marketing materials used local Singaporean KOLs

Your trading platform is open to Singapore IP addresses

A significant proportion of your investors are from Singapore

Then, MAS can assert jurisdiction and require you to comply with relevant provisions of the SFA.

This "long-arm jurisdiction" is not unique to Singapore—similar provisions exist in the US SEC and EU regulatory frameworks. However, Singapore has explicitly included it in the tokenization guidelines, sending a clear message: do not think you can evade regulation through "offshore structures."

Especially in light of the new DTSP regulations from May this year, Singapore's regulatory logic has become very clear:

If you operate in Singapore (even if it's just a few people working from home), you must have a license.

If you are not in Singapore but provide services to Singaporeans, you may also need a license.

If you neither operate in Singapore nor provide services to Singaporeans, but your activities have a "substantial impact" on the Singapore market, MAS can still regulate.

This essentially closes off all paths for regulatory arbitrage.

VI. Conclusion: Certainty is the Soil for Innovation

As I write this, the article is nearing its end. But I want to add a few more words.

In the past few years, I have seen many RWA projects fail due to "regulatory uncertainty." Some failed because legal fees were too high, some because they couldn't wait, some simply didn't know "who to seek approval from," and some couldn't raise funds at all.

What truly stifles innovation is not regulation, but uncertainty.

If the rules are clear, even if they are a bit strict, at least you know how to comply. But if the rules are vague, you can only "cross the river by feeling the stones," and every step may lead to pitfalls.

Singapore's approach this time has precisely provided the industry with "certainty." You can say these rules are strict, but you cannot say they are unclear.

But I must clarify: Singapore's guidelines do not solve all the problems of RWA; this is not a direct enactment of law.

Tokens still cannot directly equate to legal ownership—Apple's shareholder register is still at NASDAQ, the ownership of commercial real estate is still at the land registry, and on-chain records still cannot legally represent ownership. You still need Cayman SPVs, complex trust structures, and custodial agreements; these legal costs and structural complexities have not decreased at all.

But Singapore has solved a more critical issue: regulatory uncertainty.

At least now, we know how to comply, rather than groping in the fog.

For teams that genuinely want to get things done, this is actually a positive development—because compliance costs have become predictable, and legal risks have become manageable.

For those teams that only want to "harvest" investors, this is indeed bad news—because regulation has closed all loopholes.

But isn't that exactly what we want?

The RWA track is essentially about bringing "real-world assets" into the "efficiency of the digital world." If we can't even ensure basic investor protection, how can we talk about "massive applications"?

In this sense, the significance of Singapore's guidelines lies not only in "providing a set of regulatory rules" but also in declaring to the world: RWA can develop healthily within a clear regulatory framework.

After all, in financial regulation, latecomers have the advantage of learning from the experiences of pioneers and avoiding detours.

And we practitioners can vote with our feet—doing business where regulation is clearest.

As for Hong Kong, Singapore has already set an example; it needs to step up!

Reference:

https://www.mas.gov.sg/regulation/guidelines/guide-on-tokenisation-of-cmps

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。