Author: FinTax

Introduction

On April 1, 2025, the Canadian federal government announced the official cancellation of the carbon tax on fuel, a move that sent shockwaves through energy-intensive industries such as energy, manufacturing, and cryptocurrency mining. On the surface, this seems like a relief for businesses, and many have celebrated this tax benefit. However, a deeper analysis reveals that Canada has not relaxed its carbon constraints; rather, it has quietly tightened controls on the industrial side, applying pressure more precisely to large-scale emission facilities. For cryptocurrency mining companies that heavily rely on electricity, this marks the beginning of a more complex cost game.

1 Policy Change: Cancellation of the "Fuel Carbon Tax," but Carbon Prices Remain High

To understand the substantive impact of this change, it is essential to review the basic logic of carbon pricing in Canada. According to the Canadian Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, Canada's carbon tax system consists of two core parts: one is the federal fuel charge aimed at end consumers and small businesses; the other is the output-based pricing system (OBPS) for large industrial facilities. The latter was designed to protect energy-intensive industries from the direct impacts of international competition while imposing carbon costs.

The cancellation of the fuel carbon tax only means that the tax burden at the retail level has been alleviated, while the industrial carbon price, which has a profound impact on large energy users like mining companies, continues to rise. According to federal plans, this price will increase by CAD 15 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO₂e) each year from 2023 to 2030, with a final target of CAD 170 per ton. Canada's emission reduction strategy has not changed; the continuously rising compliance costs under the carbon tax will inevitably be passed down through energy prices.

2 Rising Carbon Prices: Inflation in Energy-Intensive Industries

From an economic structure perspective, the real impact of industrial carbon prices is not simply a "pollution tax," but rather an efficient transmission through the electricity pricing chain. It is worth noting that power generation companies do not pay for all their emissions. Under Canada's mainstream "output-based pricing system" (OBPS), the government sets a benchmark for emission intensity, and power plants only need to pay carbon costs for emissions that exceed this benchmark.

For example, in Ontario, the industry benchmark for natural gas power generation is set at 310 t CO₂e/GWh, while the average emissions of units are around 390 t CO₂e/GWh. This means that the actual carbon price payment is only for the difference of 80 t/GWh. However, this excess cost (when the carbon price is CAD 95 per ton) translates to an additional cost of about CAD 7.6 per MWh; if the carbon price rises to CAD 170 per ton by 2030, this figure will increase to CAD 13.6 per MWh. This mechanism then transmits downstream to mining and manufacturing industries, especially energy-intensive businesses like Bitcoin mining.

It should be noted that the impact of carbon prices is not evenly distributed across Canada, largely depending on the electricity generation mix in each province. In regions like Ontario or Alberta, which rely on natural gas as the marginal power source (i.e., the pricing source), carbon costs are more easily incorporated into wholesale electricity prices. In contrast, in regions dominated by hydroelectric or nuclear power, this transmission effect is significantly weakened. This directly leads to cost differentiation for energy-sensitive businesses like Bitcoin mining: in gas-dominated markets, rising carbon prices almost equate to a simultaneous increase in operating costs; while in regions rich in low-carbon electricity, the impact is relatively lower.

3 Dual Pressure on Mining Companies: Rising Costs and Policy Uncertainty

For the electricity-dependent Bitcoin mining industry, Canada's industrial carbon pricing system presents dual challenges that profoundly affect corporate operations and decision-making.

The first challenge is the direct increase in power generation costs due to rising carbon prices. Canadian mining companies generally use power purchase agreements (PPAs), and as industrial carbon prices continue to rise, the impact of the "carbon price adjustment clause" in electricity price contracts becomes more significant, leading to an annual increase in the unit cost of mining power. Whether linked to market electricity prices through floating contracts or seemingly stable long-term fixed contracts, neither can avoid this trend in the long run. The former will quickly reflect cost increases, while the latter will face higher carbon tax premiums upon renewal.

The second challenge arises from the complexity and uncertainty of the regulatory environment. Mining companies in Canada do not follow a single set of rules but rather a differentiated regulatory system across provinces. For example, some places (like Alberta) temporarily maintain local industrial carbon prices at lower levels to sustain industrial competitiveness, not adjusting in line with federal policies. While this approach reduces compliance burdens in the short term, it also brings significant policy risks. The federal government has the authority to assess the "equivalence principle" of emission reduction efforts across regions: if local measures are deemed insufficient by the federal government, a higher standard federal system may intervene. This potential policy shift means that "low-cost" investment decisions made by companies may face the risk of forced adjustments in the future. This uncertainty has become a critical consideration for mining companies when planning their operations in Canada.

4 Changes in Mining Company Strategies: From Cost Control to Compliance Planning

In the face of increasingly clear cost transmission paths and a complex and changing policy environment, the operational logic of Canada's cryptocurrency mining industry is undergoing a significant transformation. Companies are shifting from being passive electricity price acceptors to proactive compliance planners and energy structure designers.

First, companies are beginning to make structural adjustments in energy procurement. One strategy is to sign long-term green power purchase agreements (Green PPAs) or directly invest in renewable energy projects. The goal of these adjustment strategies is no longer limited to locking in a predictable electricity price but aims to fundamentally decouple from the existing price formation mechanism that combines natural gas marginal pricing with Canadian carbon costs. Under the OBPS framework, this verifiable low-carbon electricity structure may also provide companies with additional carbon credits, transforming compliance expenditures into potential revenue sources.

Second, the differentiated regulatory rules among provinces are giving rise to complex strategies that exploit policy differences for arbitrage. For example, in British Columbia (B.C.), the accounting boundaries of its OBPS system primarily focus on emissions within the province. This rule design means that imported electricity purchased from outside the province is not subject to carbon cost assessments. Mining companies can strategically design their electricity procurement mix (e.g., using a small amount of local electricity while purchasing large amounts from other provinces) to avoid local high-carbon electricity costs.

Additionally, the incentive mechanisms inherent in the OBPS system (i.e., obtaining exemptions by improving efficiency) are becoming a new direction for companies' technological investments. This is reflected in two aspects: first, the scale threshold, where facilities with annual emissions below a specific standard (e.g., 50,000 tons CO₂e) can qualify for exemptions, prompting companies to consider their total emissions when designing capacity; second, efficiency benchmarks, for example, under Alberta's TIER system, if industrial companies can achieve lower emission intensity than the officially set "high-performance benchmark," they can legally reduce or even completely exempt their carbon costs—potentially even generating additional revenue by selling carbon credits under certain circumstances.

The series of strategic shifts mentioned above indicates that carbon compliance is no longer a simple financial deduction. With the U.S. and Europe advancing carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAM), Canada's carbon pricing policy is evolving from a domestic issue to a key cost node in international investment, and a company's compliance capability is rapidly becoming a core competitive advantage in its financial and strategic planning.

Based on the above analysis, the cancellation of the fuel carbon tax in Canada reflects a deeper policy adjustment. The relaxation on the fuel side and tightening on the industrial side represent the federal government's decision to balance emission reduction goals with economic resilience. For energy-intensive industries like Bitcoin mining, this choice clearly points to three future trends:

First, energy costs will continue to rise, but there is room for planning;

Second, policy risks are increasing, but they can be controlled through scientific site selection and compliance arrangements;

Third, green investments and carbon credit mechanisms will become new sources of profit.

However, there exists a gap between the "knowledge" and "action" of these strategic opportunities. Companies are facing three core challenges in practice, from decision-making to implementation:

First, the "federal-provincial" dual structure brings regulatory complexity, making it difficult for decision-makers to input information. Although Canada has a federal carbon pricing benchmark, provinces are allowed to design and implement their own equivalent industrial pricing systems (such as OBPS or TIER). This results in companies facing not a unified standard but a situation of "one benchmark, multiple executions." Each province has significant differences in defining "exemption thresholds," specific industry emission benchmarks, rules for generating and using carbon credits, and even methods for accounting for imported electricity. These localized execution details make it impossible for companies to simply apply a national standard; a carbon reduction strategy validated as efficient in Province A may not receive exemptions in Province B due to different accounting methods, creating significant difficulties in formulating optimal strategies.

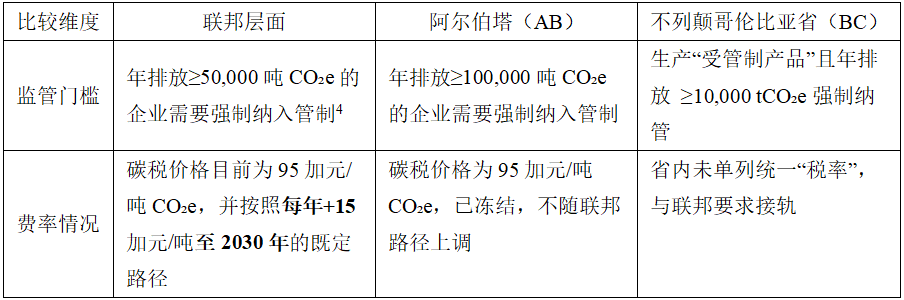

Table: Comparison of Carbon Tax Rates at the Federal Level, Alberta (AB), and British Columbia (BC)

Second, the old cost decision-making methods of companies are no longer fully applicable. In the past, the core consideration for mining companies in site selection was the single spot electricity price (/kWh). However, under the new regulations, companies must shift to considering risk weighting. Decision-makers now need to quantify those elusive variables: how much premium should be accounted for the hidden policy reversal risks behind a temporarily low carbon price in a region? More complex is the fact that investing in green energy (Trend 3) is a high capital expenditure (CAPEX) decision, while paying carbon taxes is a variable operating expenditure (OPEX)—how to assess the future gains and losses brought by these two in decision-making is not something traditional operations teams can accomplish.

Finally, the lack of compliance systems in execution teams leads to difficulties in implementing strategies. Even if decision-makers formulate a perfect strategy, they face significant challenges at the execution level. The only deliverable result of all strategies is the compliance report submitted to regulatory agencies. This requires companies to establish a cross-validation system covering legal, financial, and engineering aspects. For example, does the data scope of the MRV (Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification) system meet tax audit requirements? Is the source and attribute of interprovincial electricity consistent in legal contracts and financial accounting? Without this systemic compliance capability, any sophisticated strategy cannot be translated into real financial benefits.

6 From "Taxable" to "Adaptive," Where Do Cryptocurrency Mining Companies Go?

Currently, Canada's carbon pricing policy is entering a more refined stage. It is no longer merely a tax collection tool but a dual consideration of economic governance and industrial structure. In this system, the competition among energy-intensive enterprises depends not only on the cost of electricity but also on the depth of understanding of policies, the advancement of financial models, and the precision of compliance execution. For cryptocurrency mining companies, this is both a challenge and an opportunity—those that still rely on outdated single-cost models for site selection may suffer losses in future policy adjustments; while those that can systematically plan by integrating energy markets, tax policies, and compliance frameworks will truly possess the ability to navigate through cycles.

However, as analyzed earlier, from strategic formulation to compliance implementation, companies are facing three core challenges: insufficient information input, outdated decision models, and lack of compliance execution. In this trend, carbon tax planning, energy structure design, and policy risk assessment have become the core logic of a new round of competition for mining companies. Therefore, the shift from a past passive "taxable" business model to an active "adaptive" strategic choice has become an unavoidable reality for mining companies.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。