This article is from: Doug Colkitt, founder of Ambient Finance

Translation|Odaily Planet Daily (@OdailyChina); Translator|Azuma (@azumaeth)_

Editor’s note: On October 11, the cryptocurrency market experienced an epic crash (see “The Night of October 11: The Crypto Market Plummets, $20 Billion Vanishes” for details).

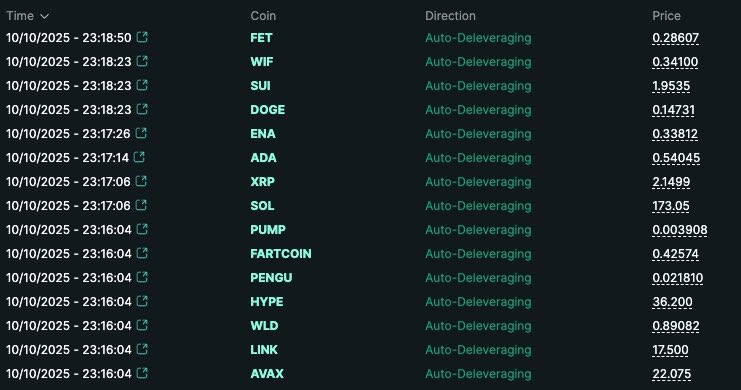

Although the market has shown signs of recovery, discussions surrounding massive liquidations and various perpetual contract exchanges have not cooled down, especially after Hyperliquid confirmed that the protocol executed its "Auto-Deleveraging" (ADL) mechanism for the first time since its operation began two years ago, making ADL a focal point of market discussions.

What exactly is ADL? Why are my profitable positions being automatically deleveraged or even liquidated? Doug Colkitt, founder of Ambient Finance, recently provided a straightforward and detailed explanation of this mechanism on his personal X account. Below is the original content by Doug Colkitt, translated by Odaily Planet Daily.

In the recent crash, many people woke up to find their perpetual contract positions forcibly liquidated, wondering, “What exactly is the Auto-Deleveraging mechanism (ADL)?”

Here is a concise yet comprehensive explanation of this mechanism. What is ADL? How does it work? Why does such a mechanism exist?

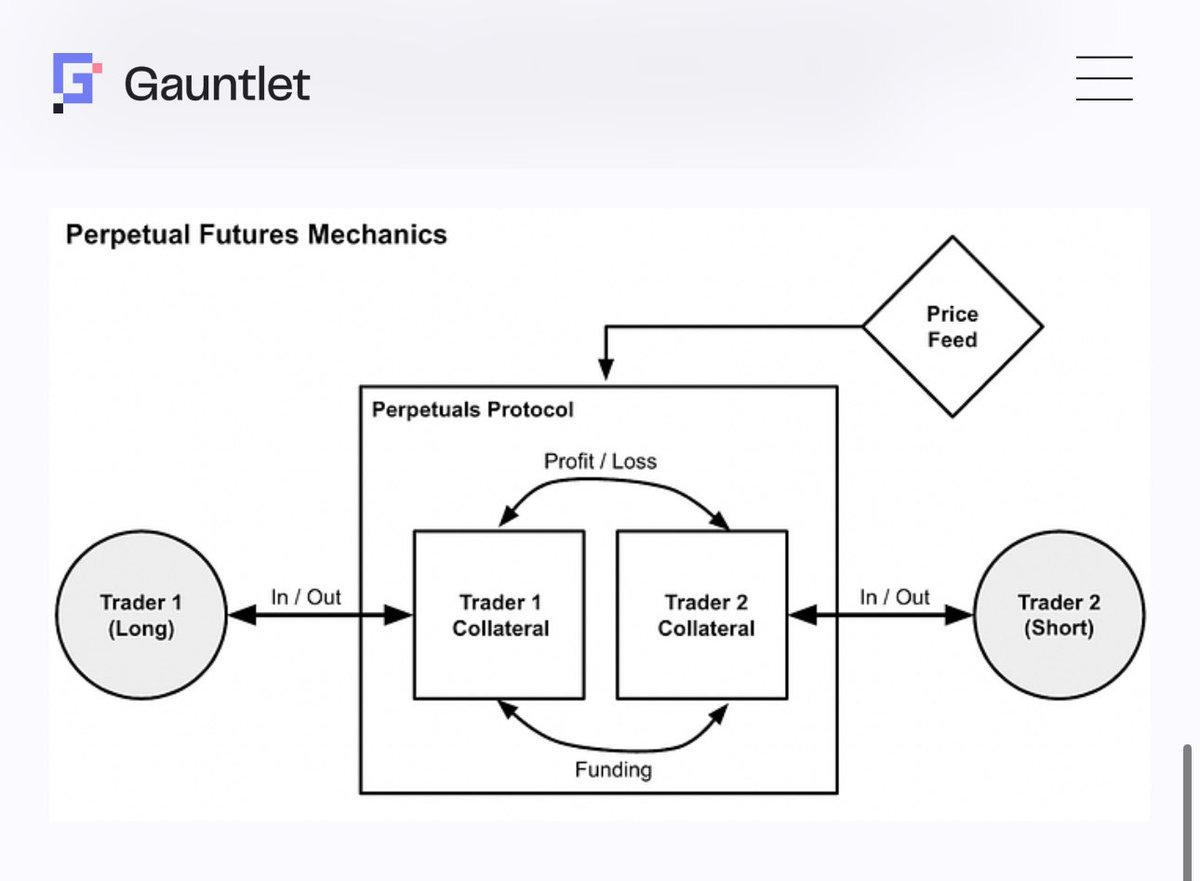

First, we need to take a step back and think from a more macro perspective—what exactly is the perpetual contract market, and what does it fundamentally do?

For example, when you look at a perpetual contract market for BTC, there is actually no real BTC present in the market; there is only a large pool of idle cash.

Everything that the perpetual contract market (or more broadly, the derivatives market) does is essentially redistributing that pool of cash. It moves this cash back and forth among participants according to a specific set of rules, constructing a synthetic asset that “looks like BTC,” even though there is no real BTC in this system.

The most important rule is: There must be both long and short positions in the market, and the total long positions must be perfectly balanced with the total short positions—otherwise, the entire system cannot function. Both longs and shorts will contribute cash in the form of margin into that pool of funds, which will then be redistributed based on the fluctuations in BTC prices.

In this process, if BTC prices fluctuate too much, some participants may lose all their cash. At that moment, they will be kicked out of the system—this is known as “liquidation.”

Remember, longs can only make money when shorts are losing, and vice versa. So when one side runs out of money to lose, they can no longer stay at the table.

Additionally, every short position must be precisely hedged by a solvent long position. If a long in the system can no longer afford to lose money, that, by definition, means the corresponding short side can no longer make money. The same goes for the reverse.

Therefore, when a long position is liquidated, the system must either:

- 1. Introduce a new long position with new cash into the pool;

- 2. Liquidate the corresponding short position to bring the entire market back to a balanced state.

Ideally, all of this would be smoothly accomplished through normal market mechanisms. As long as there are willing buyers at reasonable prices in the market, there is no need to force anyone to take action. In a typical “liquidation” process, the system will directly use the same order book as regular perpetual contract trading to execute.

In a healthy and liquid perpetual contract market, this process works perfectly. When a long position is forcibly liquidated, its position will be sold into the order book, taken by the highest bid in the market. This buy order will then become a new long in the system, bringing new cash into the pool. At this point, the market is rebalanced, and each participant receives the outcome they deserve—everything goes smoothly, and everyone is happy.

However, sometimes the market lacks sufficient liquidity. Or at least, the depth of the order book is insufficient to complete the liquidation without exceeding the remaining funds of the original position. This becomes a problem: because it means the cash in the pool is not enough to support the settlement of everyone’s profits and losses.

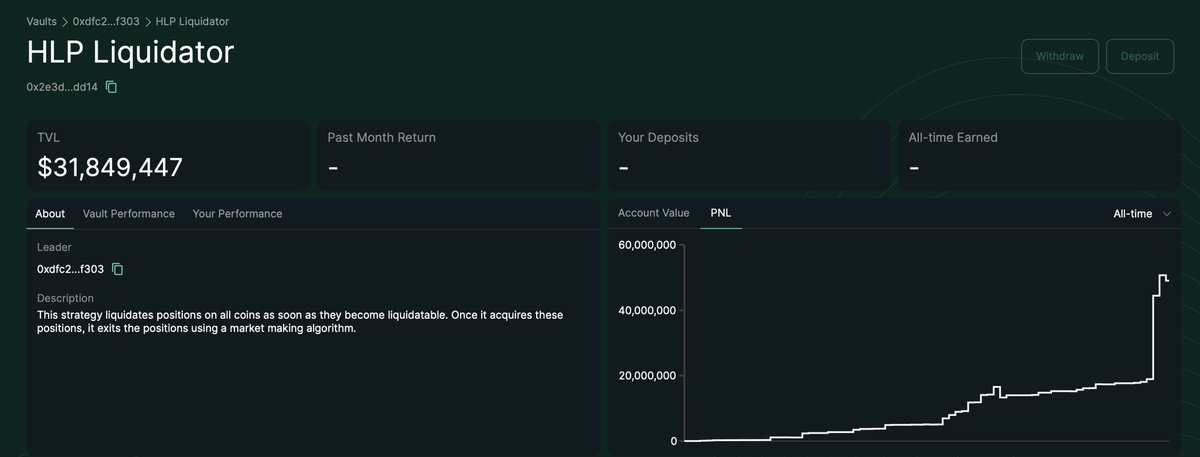

Typically in such cases, the system will enter the next layer of the “waterfall model”—intervention by a “vault” or “insurance fund.” This vault is often a special fund pool supported by the exchange, which intervenes and takes on the counterparty of the forcibly liquidated positions during extreme liquidity events.

Generally, the insurance fund is quite profitable over the long term, as it can buy in at deep discounts and sell during high volatility, earning the spread profits during extreme market fluctuations. For example, Hyperliquid's insurance fund made about $40 million in just one hour during tonight's market.

But it’s important to understand that the insurance fund is not magic; it is just an ordinary participant in the system. Like other traders, it must also put cash into the pool, adhere to the same market rules, and can only operate within its limited risk tolerance and capital range. Therefore, this mechanism must have one final step.

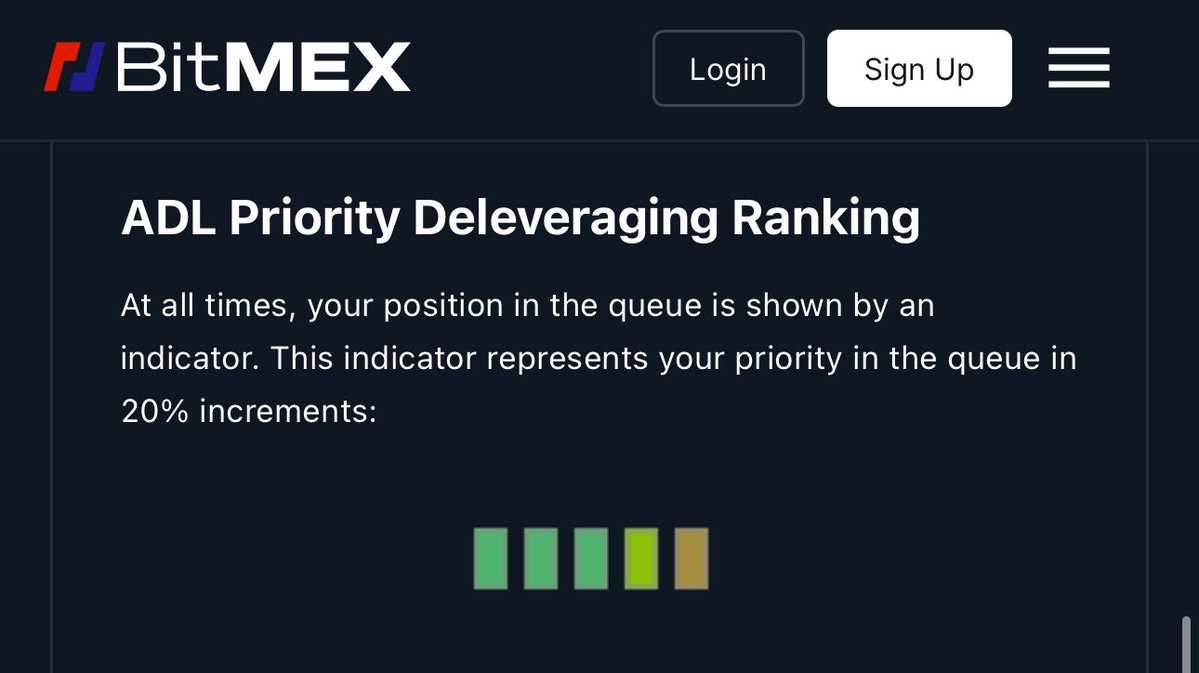

ADL is that final step. ADL is the last line of defense in the entire “waterfall model,” often seen as a “last resort” because it does not occur through market matching but rather forces some traders to settle and exit their positions. Its occurrence is very rare, so rare that even experienced perpetual contract traders often have little intuitive impression of it.

You can think of ADL like an oversold flight. The airline first tries to resolve the overbooking issue through a “marketized” approach—they continuously raise the compensation amount, hoping some passengers will agree to switch to a later flight. But if no one is willing to give up their seat, the airline ultimately has no choice but to forcibly remove some passengers from the plane.

In the perpetual contract market, the situation is similar. If the funds of the longs have been exhausted and no new funds are willing to come in to take over their positions, the system has no choice but to forcibly “remove” some shorts from the plane—meaning liquidating their positions to restore balance to the entire system.

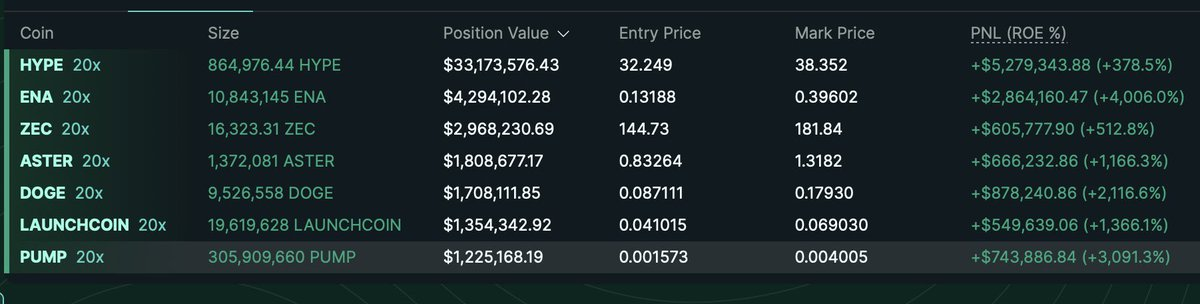

As for which positions the system chooses to liquidate and at what price, there can be significant differences between exchanges. Generally, the ADL system will select positions to be liquidated from the “most profitable side,” with the specific order usually based on three indicators:

- Profit—the more profit, the higher the priority;

- Leverage—the higher the leverage, the higher the priority;

- Position size—the larger the position, the higher the priority.

In other words, the “big players” who make the most profit, have the largest positions, and the highest leverage will be the first to be forcibly liquidated by the system.

Naturally, people often feel dissatisfied with ADL because it does seem unfair—you are clearly winning the most and in the best position, yet you are forced to exit the market. But this mechanism must exist to some extent. No matter how excellent an exchange's system is, it cannot guarantee that there will always be an infinite number of “losers” in the market to satisfy the profits of the winners.

You can think of it as playing poker. You enter the casino and keep winning at table after table. You bust one table, then go to the next, and the next—eventually, everyone else in the casino runs out of chips. This is the essence of ADL.

The true beauty of the perpetual contract market lies in the fact that it is a zero-sum system, which means the entire system will never go bankrupt overall, as there is not even any real BTC to “devalue,” only a large pool of cash that is constantly being redistributed. Just like the conservation of energy in thermodynamics—within this closed system, value is neither created nor destroyed out of thin air.

From a certain perspective, ADL is somewhat like the ending of the movie “The Truman Show.” The perpetual contract market constructs an extremely realistic and intricate simulation of the spot market, but ultimately, all of this is virtual. Most of the time, we do not need to be aware of this layer of “fiction,” but occasionally when the market reaches its limits—we will hit the “boundaries of this simulated world.”

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。