Technology companies refuse to disclose information under the guise of trade secrets, conceal their identities through subsidiaries to obtain tax benefits, promise clean energy but delay emission reduction plans, and ultimately pass the costs of grid upgrades onto consumers.

Written by: Zhi Dongxi

Source: Wall Street Watch

Major technology companies are building data centers at an unprecedented pace, with more than two data centers rising each week in the United States alone. Data centers are the engines of AI's rapid growth, storing photos, videos, and social network information; however, there are almost no official records showing how many of these facilities exist, where they are located, or who controls them.

To answer these questions, investigative journalists from the American media outlet Business Insider decided to create a map of data centers across the United States. They used records of backup generator applications for data centers as a starting point, searching public records state by state to gradually reveal data centers that have long been hidden under the label of "trade secrets."

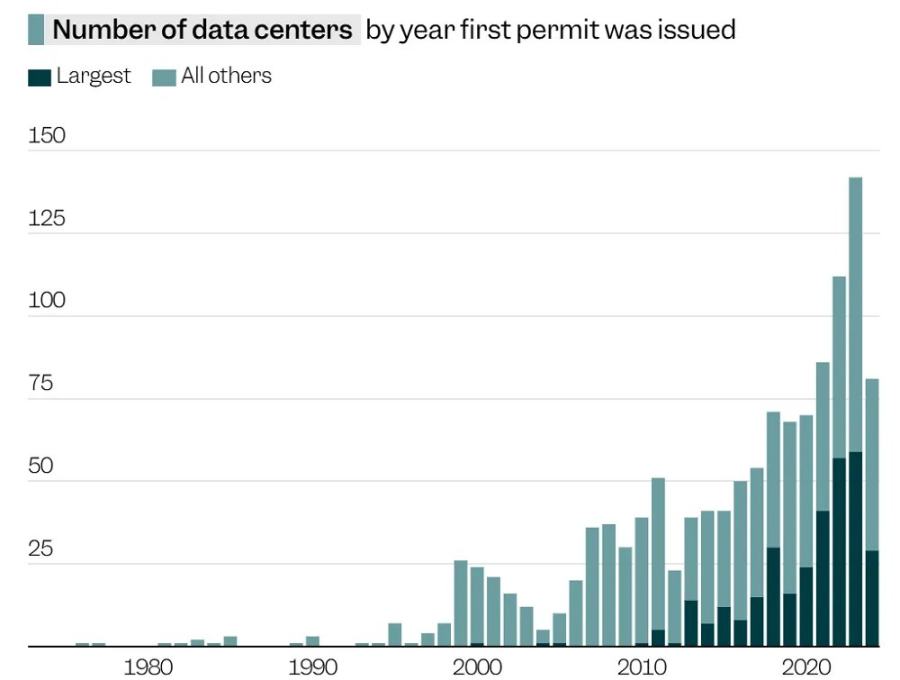

The investigation yielded shocking results: as of 2024, there are as many as 1,240 large data centers built or approved for construction in the United States, a nearly 300% increase over the past 15 years.

These data centers, surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, are concentrated in areas like Virginia and Arizona, consuming enough electricity and water resources to rival entire cities, placing immense pressure on local environments and infrastructure.

Large data centers can consume over 2 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity annually, enough to power 200,000 households for a year. Moreover, 43% of data centers are located in areas of high or extreme water scarcity and use drinking water for cooling.

In response to the enormous energy pressure brought by data centers, many regions have postponed their plans to adopt clean energy and need to invest tens of billions to even hundreds of billions of dollars to upgrade infrastructure. By 2039, electricity costs in Virginia could rise by more than 50% due to related construction.

Even more concerning is that data centers are often sited close to residential areas to ensure more reliable infrastructure. Business Insider's reporters first visited Loudoun County in Virginia, known as the "Silicon Valley of Data Centers," where data centers have significantly impacted people's daily lives.

Documentary link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-8TDOFqkQA&t

01. Residential areas are only a hundred meters away from data centers, with some homes surrounded by them

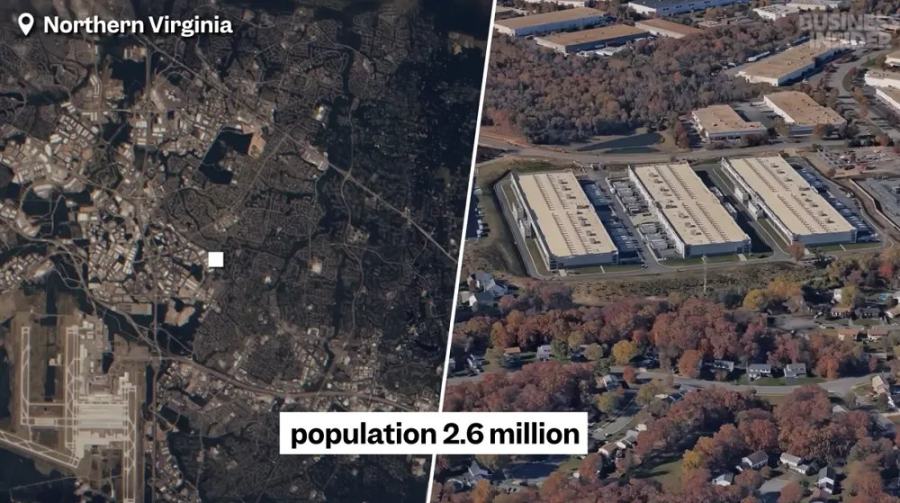

One-third of the world's internet traffic passes through Virginia. Loudoun County in the state has the highest density of data centers globally, with 329 data centers consuming a quarter of the state's electricity.

At first glance, this appears to be an ordinary American suburb, but from above, the massive white server rooms are neatly arranged, resembling modern factories.

Tech companies choose this location because of its reliable electricity, abundant water resources, tax incentives, and cheap land. However, these advantages also mean that data centers are often just a wall away from residential communities.

Northern Virginia, where Loudoun County is located, is the most densely populated area in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area and one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States. Data centers are being rapidly and massively constructed here.

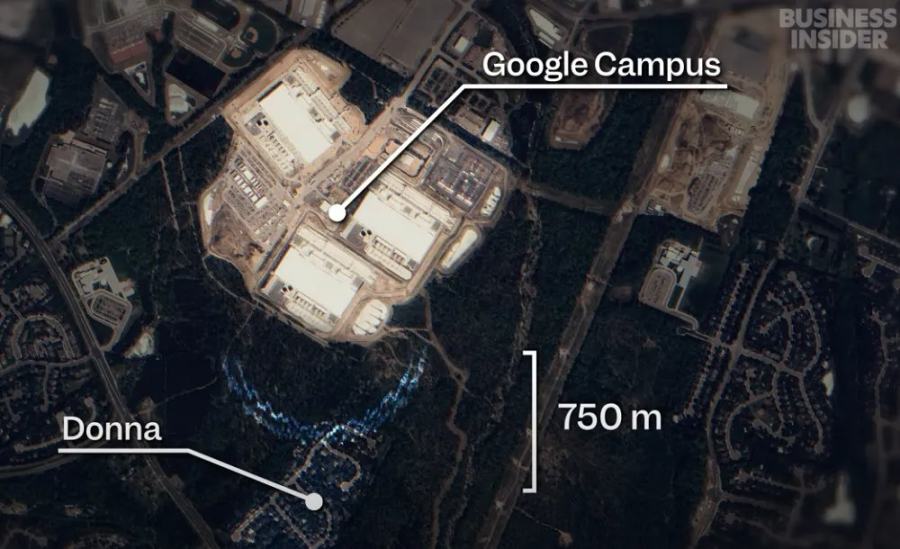

Donna Gallant is one of those affected by the construction of data centers. She has lived quietly in Prince William County in Northern Virginia for 30 years, the fourth homeowner on her street, witnessing the area's development.

In 2021, Google built a data center just 750 meters from her home. Since then, the nighttime noise has caused her anxiety and sleeplessness, forcing her to leave her second-floor bedroom and sleep on the first floor with noise-canceling headphones.

She tried to seek information about the data center from on-site staff and government officials but was met with the response: "We signed a confidentiality agreement and cannot discuss it."

Worse still, this is just the beginning. In the coming years, more data centers will emerge around Donna's community. A piece of land originally designated for housing was re-zoned in 2023 for industrial use, paving the way for data center construction. A 75-foot (approximately 22.8 meters) data center is now being prepared to be built right across from the residential area.

Prince William County currently has over 70 data centers, and if the overall plan is fully realized, along with nearby Loudoun County, it will have more data centers than the entire country of Russia.

Donna attempted to legally challenge the re-zoning, but her lawsuit was dismissed. She believes that while the world does need data centers, it is wrong to build them next to people's homes.

Similar stories are emerging across the United States. Carlos Lianes, a resident of Manassas, Virginia, measures the noise from the Amazon data center at his doorstep daily and shares it with local residents' organizations. He says, "You can not only hear these sounds but also feel them directly."

The source of the aforementioned noise is the cooling systems of data centers. In many data centers, large cooling systems extract hot air and circulate it through air conditioning units to cool down. The most common cooling method involves using cold water to absorb heat and releasing it through cooling towers, with cooling systems and fans producing a continuous hum.

▲ These square boxes are the cooling systems of data centers

Their noise levels are typically below the limits allowed by the government for industrial zones near residential areas. However, the buildings in these residential areas were not designed to accommodate the constant hum of modern data centers.

Low-frequency vibrations even cause Carlos's windows to shake, and he had to spend $20,000 to replace them with soundproof windows, yet he still cannot sleep. The nighttime humming troubles him and his 7-year-old son, who even thinks there is a "spaceship" outside. At one point, Carlos even organized for his family to move to the basement to escape the vibrations.

After intervention from the residents' committee and local authorities, the data center operator initially tried to reduce the noise by placing materials around the fans on the building's roof. These measures ultimately proved ineffective, and the operator replaced the fans themselves, installing higher exhaust outlets.

After these improvements, the noise level did decrease, but Carlos and his neighbors claim they can still feel the vibrations from the data center.

Carlos states that he does not oppose the construction of data centers but believes that such constructions should not cross the line—meaning they should not be too close to residential areas, schools, etc. Unfortunately, in the coming years, more data centers will be put into operation in Carlos's community.

Amazon responded that its noise is "well below regulatory standards," but the physical and mental impacts felt by residents can no longer be ignored. The American Public Health Association warns that long-term noise exposure may lead to cardiovascular diseases and mental health issues.

02. Unveiling the Mystery of Data Centers through Permits: Amazon, Microsoft, and Google Rank in the Top Three

How many data centers are affecting the lives of local residents? Which companies should be held accountable for this?

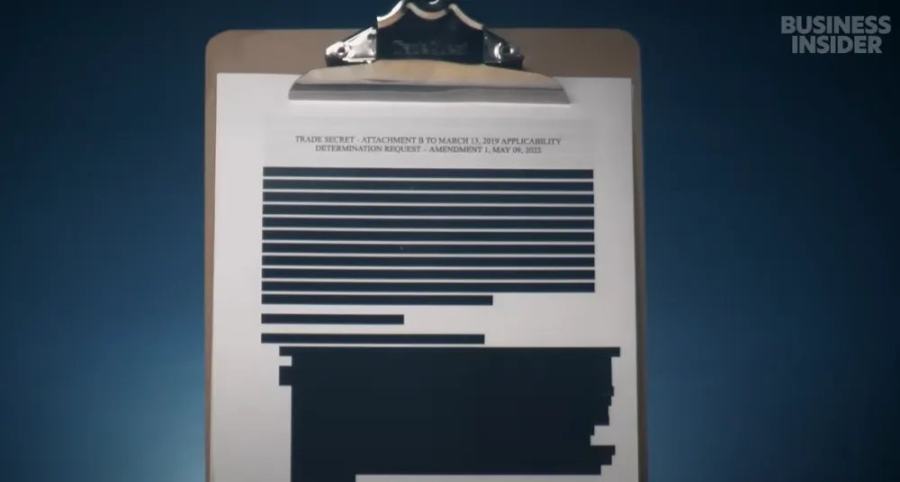

Currently, there is no complete public directory of data centers in the United States, no official map, and no dedicated regulatory agency to provide answers. Attempts to obtain information through the Freedom of Information Act often result in heavily redacted documents or refusals citing "trade secrets."

▲ Documents related to data centers are often heavily redacted

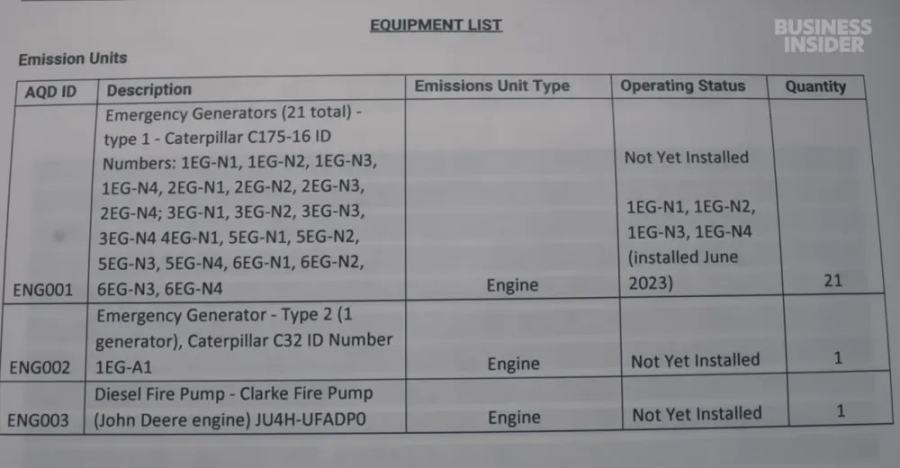

Business Insider's investigative journalists took a different approach. They discovered that almost all data centers share a common feature: backup generators used to keep the data centers operational during power grid failures. Installing generators requires applying for air quality permits, so the team decided to start from this breakthrough.

They submitted public records requests in each state for all air quality permits issued to data centers. The permit documents indicated the capacity of the generators, allowing them to estimate the power consumption of the data centers and often providing clues about the true owners of the data centers.

▲ Some air quality permits obtained by Business Insider

For example, near Columbus, Ohio, at least 164 backup generator permit applications were submitted by a company named Magellan Enterprises LLC. However, upon digging deeper into the official records, the reporters found that it actually belongs to Google.

Business Insider's investigative journalists tracked down hundreds of similar leads, ultimately creating the most comprehensive statistics on data centers in the United States to date.

Data shows that in the past 15 years, the construction of data centers in the United States has entered a period of rapid development, with several major clusters emerging. Northern Virginia and Maricopa County in Arizona are the areas with the highest density of data centers.

This chart shows the explosive growth of data centers in the United States over the past 20 years. In 2010, there were 311 data centers built or approved for construction in the U.S., while in 2024, this number has risen to 1,240, nearly four times that of 2010.

By the end of 2024, Amazon will have 177 data centers with construction permits, followed closely by Microsoft, Google, Meta, and QTS (a data center solutions provider under Blackstone Group).

Computing equipment itself requires a significant amount of electricity, and the cooling systems and water pumps of the buildings also need power. The largest data centers can consume over 2 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity annually, enough to supply 200,000 households.

Electricity is just part of the problem. The cooling systems of data centers require a large amount of water. In water-rich areas, this is not an issue, but in drought-stricken regions like Arizona, the situation is entirely different.

The following image shows the site of a new data center in Arizona, where the only way to obtain water is through well drilling.

Extreme drought is sweeping across Arizona. The state's primary water source is the Colorado River, which has seen a 20% reduction in flow since 2000. Therefore, every drop of water is crucial as it flows through Arizona.

However, when Business Insider overlaid the previously created data center map, they found that a large number of data centers are flooding into these drought areas. Cheap electricity may be one of the driving factors behind this behavior.

For example, Microsoft built its first data center in the area in 2019, and six years later, there are already five Microsoft data centers in the region, with another new one under construction.

These data centers, located on the outskirts of towns, are actually built on plowed farmland. From the permit documents, it can be seen that this new cluster from Microsoft could be very large, with a total of 280 generators and a total capacity of nearly 800,000 kilowatts.

Documents indicate that Microsoft expects each data center to use 3.79 million liters of water per day, totaling 693.6 million liters annually, equivalent to the annual water usage of a city with a population of 61,000.

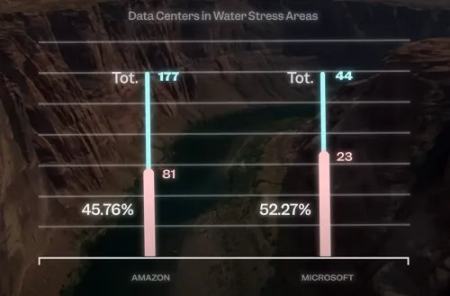

The investigation found that 43% of large data centers are located in areas of high or extreme water scarcity, and these data centers use drinking water. Amazon has 45.76% of its data centers in areas of high water scarcity, while Microsoft's percentage reaches 52.27%.

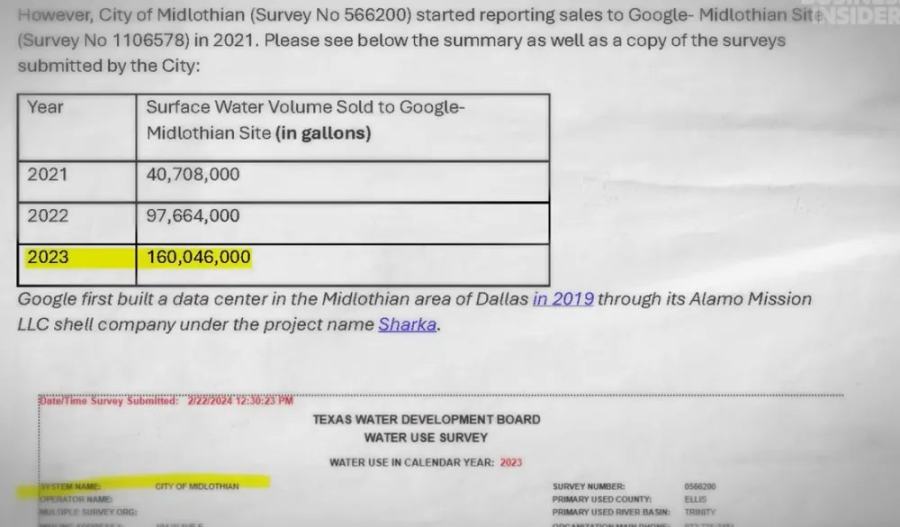

The water usage of data centers is also considered a trade secret. However, Business Insider managed to obtain over 50 relevant data points. For example, Google's data center in Midlothian, Texas, consumed 610 million liters of water in 2023; the Kindred data center in Colorado consumed 320 million liters in the same year.

In Arizona, whether from the Colorado River or groundwater extraction, water is strictly regulated. However, local municipal authorities can decide how to use their water quotas, and many areas in the state have virtually no restrictions on companies drilling wells.

Many tech companies have pledged to achieve "water positive" benefits by 2030, meaning they will restore or save more water than they use. However, this is mainly achieved through the practice of water rights offsets, which involves paying others to save water in the company's name, failing to alleviate local resource pressures.

Complicating matters, when data centers reduce water usage and switch to air conditioning for cooling, electricity consumption significantly increases, further raising carbon emissions.

03. AI Data Centers Push the Grid to Its Limits; Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction Goals Delayed

Although data centers are hailed as the "cornerstone of the digital economy," the economic benefits they have brought so far are limited. Even the largest data centers employ no more than 150 permanent staff, with some having fewer than 25. Nevertheless, states continue to compete to offer tax incentives.

So far, Business Insider has tracked 37 states providing tax incentives for data centers, covering exemptions on building materials, equipment, and discounted water and electricity rates. Even as employment commitments repeatedly fall short, tax incentives continue to be issued on a large scale.

Meanwhile, Meta, Google, and Microsoft plan to invest $64 billion, $75 billion, and $80 billion, respectively, by 2025 for the expansion of new facilities and equipment.

McKinsey estimates that by 2028, U.S. data centers could consume 600 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity, accounting for 12% of the nation's total electricity consumption, far exceeding the 4% in 2023, a scale unprecedented. These AI-driven data centers are pushing the grid to its limits.

Faced with such pressure, many power suppliers choose to abandon or delay their plans to phase out fossil fuels. In Nebraska, the two largest power companies in the state had promised years ago to achieve net-zero emissions in electricity production by 2050. However, Meta's data center in Springfield, Nebraska, consumes as much electricity as 400,000 households in a year.

To meet this demand, the state's largest public utility voted to postpone the closure of a coal-fired power plant in Omaha and plans to build two new natural gas power plants in 2025, which also means that the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 may not be achievable.

Satellite data shows that the carbon dioxide emissions from the North Omaha power plant were estimated at 300,000 kilograms per hour in June 2023.

In addition to the enormous electricity consumption, the backup diesel generators of data centers also emit a large amount of harmful pollutants, even if they only run for a few hours each month.

Currently, many large tech companies have announced investments in various clean energy projects, such as solar, wind, and even nuclear energy. In Pennsylvania, Microsoft has reached an agreement: when the notorious Three Mile Island nuclear power plant (which experienced a partial meltdown in 1979) resumes operations in 2027, Microsoft will purchase electricity from that plant.

▲ Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant

However, these companies often offset emissions by purchasing renewable energy credits rather than directly changing their energy structure. The problem is that the fragile and decentralized grid may not be able to support the energy demands of data centers. If large-scale infrastructure upgrades are needed, the ultimate burden may fall on consumers.

Amazon, Microsoft, and Google all claim they are willing to bear the full costs of grid upgrades, including high-voltage transmission lines, but there is already evidence that these costs are being passed on to consumers.

In Virginia, Dominion Energy disclosed that to meet the demands of data centers and electric vehicles, its electricity production needs to roughly double by 2039. This expansion is expected to cost up to $103 billion, and residential electricity bills could rise by 50%.

Despite this, some states are still striving to attract data centers. In Virginia, nearly $1 billion in tax breaks were provided for 56 data center projects in the 2023 fiscal year.

The case of New Albany, Ohio, is even more typical. In 2017, a mysterious company named Sidecat LLC promised to build two giant data centers on 300 acres of land in exchange for at least 15 years of 100% property tax exemption, worth about $60 million. It was later revealed that it was actually a subsidiary of Meta.

04. Conclusion: The AI Construction Frenzy Continues; Who Bears the Silent Costs?

This construction frenzy under the banner of AI is impacting the energy landscape, environmental ecology, and community life in the United States and around the world. However, the question remains: as these giant data centers continue to grow, who truly bears the costs? The pressure on the grid, the strain on water resources, and the social costs brought by tax incentives—these invisible costs may largely fall on ordinary residents and consumers.

For residents like Donna and Carlos, the choices are becoming increasingly difficult. The roar of data centers and the potential competition for electricity and water resources are forcing them to leave their homes. Donna believes that many of her neighbors are unaware of the severity of this issue, and she helplessly says, "It breaks my heart, but I can only fight for so long. After that, I will raise the white flag, pack my bags, and leave."

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。