Original Author: thiccy

Original Translation: Block unicorn

This article explores the shift in risk preference from frenzy to the worship of grand prizes, as well as its broader social implications. It involves some basic mathematical concepts, but is worth a read.

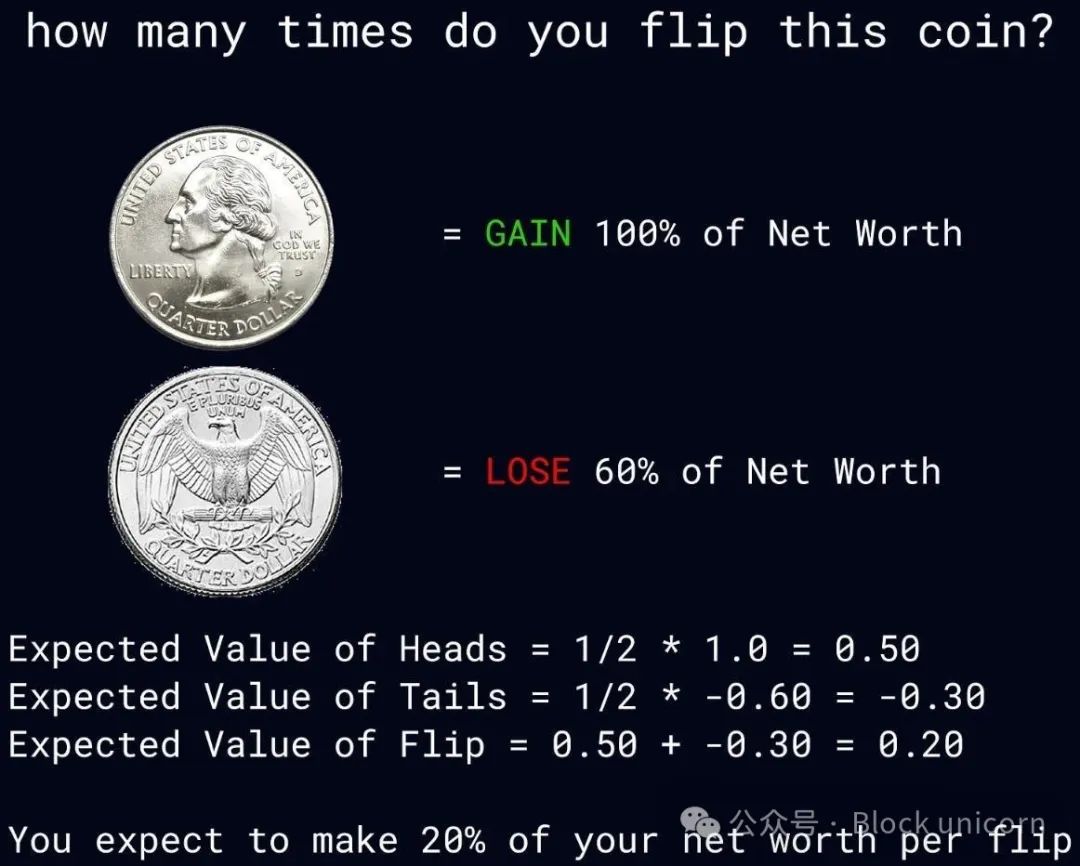

Imagine you are playing a coin toss game. How many times would you toss?

At first glance, this game looks like a money-printing machine. The expected return for each coin toss is 20% of your net worth, so theoretically, you should toss the coin infinitely, eventually accumulating all the wealth in the world.

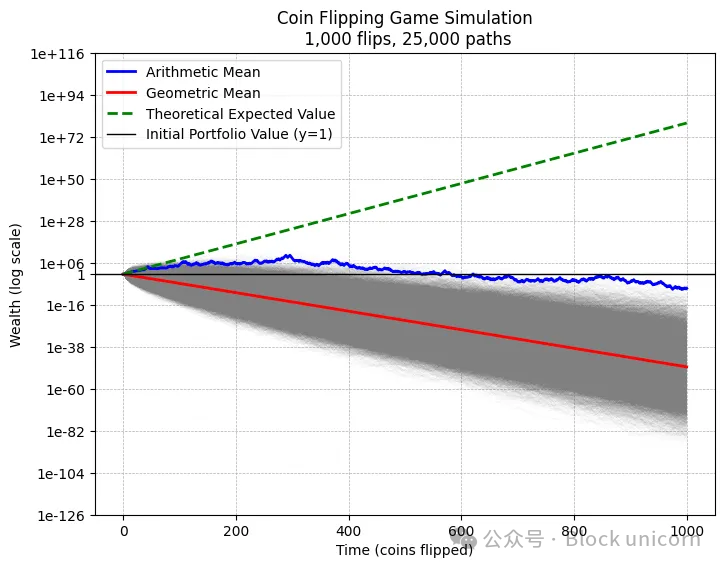

However, if we simulate 25,000 people each tossing a coin 1,000 times, almost everyone's results are close to $0.

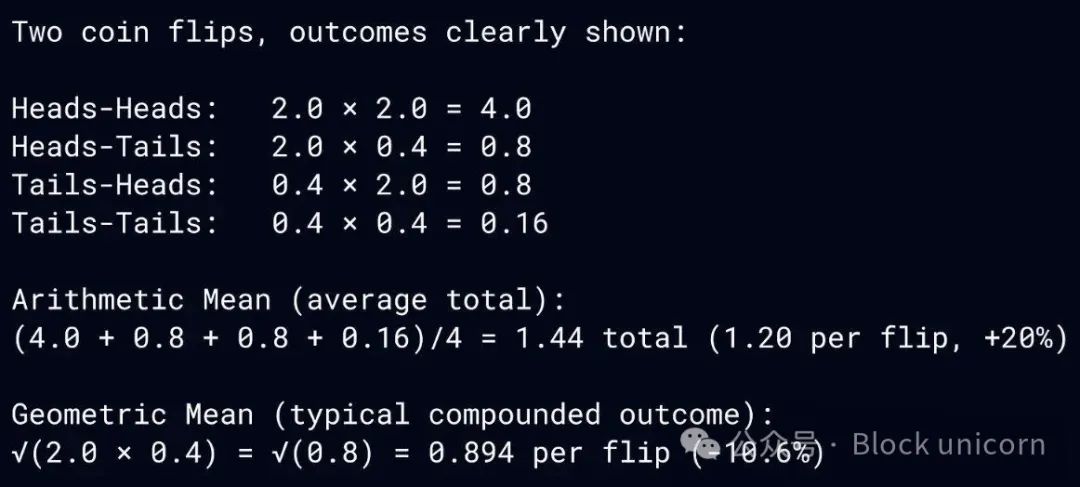

The reason almost all results trend towards $0 lies in the multiplicative nature of repeated coin tossing. Although the expected value of the game (i.e., the arithmetic mean) increases your wealth by 20% with each toss, the geometric mean is negative, meaning that in the long run, tossing the coin is actually negatively compounding.

What’s going on? Here’s an intuitive explanation:

The arithmetic mean measures the average wealth created by all possible outcomes. In our coin toss game, wealth is heavily skewed towards the rare grand prize scenarios. The geometric mean, on the other hand, measures the expected wealth in the intermediate outcomes.

The above simulation illustrates this difference. Almost all paths gradually converge to zero. In this game, you need to toss heads 570 times and tails 430 times to break even. After 1,000 coin tosses, all expected values concentrate on just 0.0001% of the grand prize outcomes, which are the extremely rare cases of tossing a large number of heads.

The difference between the arithmetic mean and the geometric mean constitutes what I call the "Grand Prize Paradox." Physicists refer to it as the "ergodicity problem," while traders call it "volatility resistance." When expected values are hidden in rare grand prizes, you cannot always rely on them. The excessive pursuit of grand prizes can turn positive expected values into a straight line to zero. In the world of compound returns, dosage determines success or failure.

The early 2020s cryptocurrency culture is a vivid illustration of the Grand Prize Paradox. SBF (Sam Bankman-Fried) sparked a discussion about wealth preferences in a tweet.

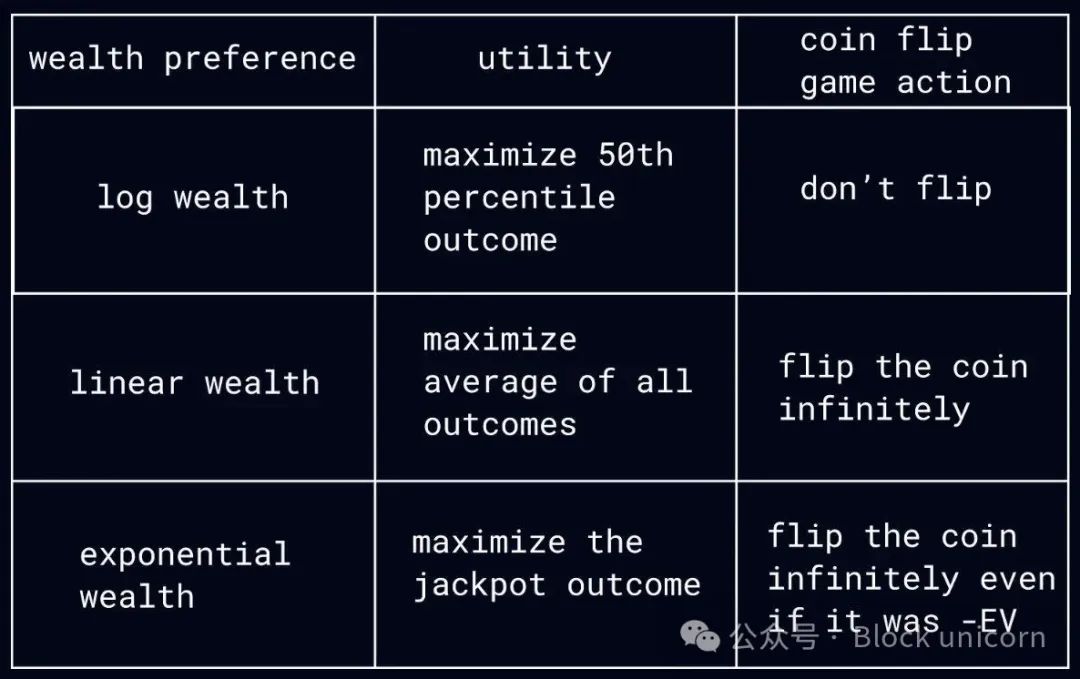

Logarithmic wealth preference: Each dollar is worth less than the previous dollar, and as wealth grows, your risk preference shrinks.

Linear wealth preference: Each dollar is valued the same, regardless of how much you have earned, and your risk preference remains constant.

SBF proudly claimed he had a linear wealth preference. He believed that since his goal was to donate all his wealth, the importance of doubling from $10 billion to $20 billion was the same as going from $0 to $10 billion, making it logically worthwhile to make large, high-risk bets from a civilizational perspective.

Su Zhu of Three Arrows Capital echoed this linear wealth preference and further proposed an exponential wealth preference.

- Exponential wealth preference: Each new dollar of wealth is more valuable than the previous dollar, so as wealth grows, you increase your risk preference and are willing to pay a premium for grand prizes.

Here are the three types of wealth preferences and their correspondence to the above coin toss game.

Given our understanding of the Grand Prize Paradox, it is evident that SBF and Three Arrows Capital are, in a sense, tossing the coin infinitely. This mindset is precisely how they initially accumulated their wealth. Similarly, it is not surprising in hindsight that both SBF and Three Arrows Capital evaporated $10 billion in wealth. Perhaps in some distant parallel universe, they are billionaires, which might justify the risks they took.

These crashes are not just cautionary tales about the mathematics of risk management; they reflect a deeper macro-cultural shift towards linear or even exponential wealth preferences.

People expect founders to adopt a linear wealth mindset, taking on significant risks to maximize expected value, as they are the gears in the venture capital machine that relies on power law distributions for success. The stories of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg going all-in and ultimately amassing the largest personal fortunes in the world reinforce the myth that drives the entire venture capital industry, while survivor bias cleverly overlooks the millions of founders whose fortunes have vanished. Only a few elites who can cross the increasingly steep power law threshold can achieve redemption.

This pursuit of ultra-high risk has permeated everyday culture. Wage growth has severely lagged behind the compounding growth of capital, leading ordinary people to increasingly view negative expected value grand prizes as their best opportunity for genuine upward mobility. Online gambling, zero-day options, retail meme stocks, sports betting, and crypto meme coins all demonstrate the phenomenon of wealth preference growing exponentially. Technology has made speculation effortless, while social media spreads every new story of overnight wealth, drawing a broader audience into a massive losing gamble like moths to a flame.

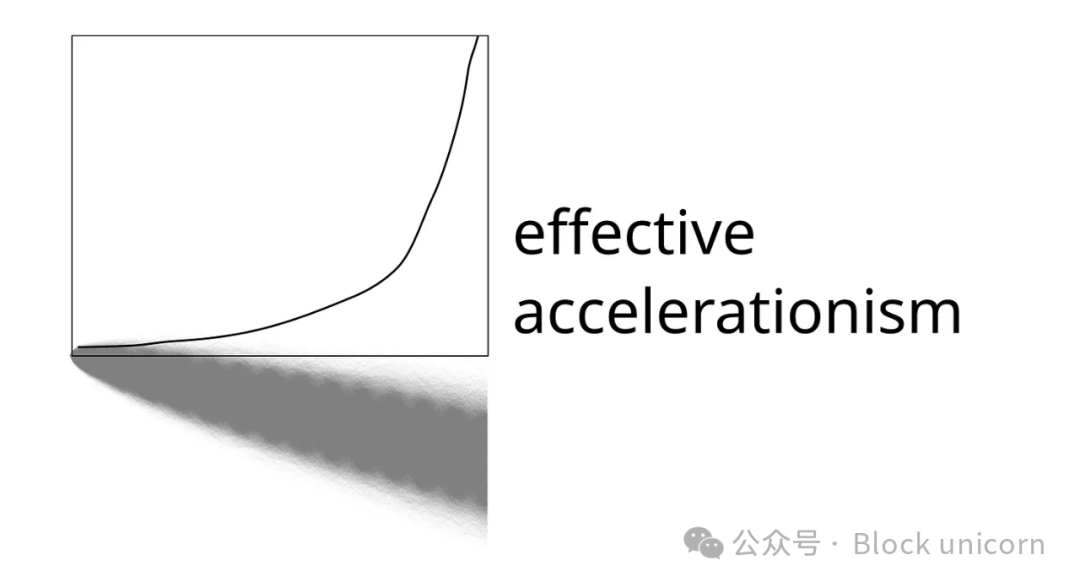

We are gradually becoming a culture that worships grand prizes, and the value of survival is increasingly reduced to zero.

Artificial intelligence has exacerbated this trend, further devaluing labor and intensifying the winner-takes-all dynamic. Tech optimists dream of a prosperous post-general AI world where humans devote their time to art and leisure, but it looks more like billions of people chasing negative-sum capital and status "grand prizes" on a universal basic income (UBI) allowance. Perhaps the "only up" e/acc banner should be redrawn to reflect the countless paths to zero along the way, which would reveal the true contours of the "Grand Prize Era."

In its most extreme form, capitalism behaves like a collectivist hive. The mathematics of the Grand Prize Paradox suggests that civilization views humans as interchangeable labor, rationalizing the sacrifice of millions of worker bees to maximize the linear expected value of the entire hive. This may be the most effective for overall growth, but it severely distributes purpose and meaning.

Marc Andreessen's declaration of technological optimism warns: "Humans should not be caged; humans should be useful, productive, and proud."

However, the rapid advancement of technology and the shift towards increasingly aggressive risk-taking incentives are precisely pushing us toward the outcome he warned against. In the "Grand Prize Era," the engine of economic growth comes at the expense of our fellow humans. Utility, productivity, and pride are increasingly reserved for a privileged few who win in competition. We have raised the average at the expense of the median, leading to an ever-widening gap between liquidity, status, and dignity, thus breeding a negative-sum cultural phenomenon throughout the economy. The resulting externalities manifest as social unrest, from electoral agitators to violent revolutions, which could cause significant losses to the compounding growth of civilization.

As someone who makes a living trading in the cryptocurrency market, I have witnessed the decline and despair brought about by this cultural shift. Just like the grand prize simulation, my victories are built on the failures of a thousand other traders. This is a monument to the waste of human potential.

When industry insiders seek trading advice from me, I can almost always spot the same pattern. They all take on excessive risks and incur significant losses. Behind this often lies a scarcity mindset, an inescapable sense of "falling behind," and an impulse to make quick profits.

My answer is always the same: Instead of increasing risk, accumulate more advantages. Don’t ruin yourself in the pursuit of grand prizes. Logarithmic wealth is what matters most. Maximize the 50% outcomes. Create your own luck.

Avoid significant drawdowns. You will eventually reach your goals.

But most people can never sustain an advantage. "Win a few more times" is not a scalable suggestion. In the fierce competition of technological feudalism, meaning and purpose are always winner-takes-all. This brings us back to the question of meaning. Perhaps what we need is a new religious revival that reconciles ancient spiritual teachings with the realities of modern technology.

Christianity spread because it promised salvation for everyone. Buddhism became widely known for the idea that anyone can attain enlightenment.

Modern systems must do the same, providing dignity, purpose, and a path forward for all, so that they do not destroy themselves in the pursuit of grand prizes.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。