Tokens enable true digital ownership.

Authors: Miles Jennings, Scott Duke Kominers, Eddy Lazzarin

Compiled by: Deep Tide TechFlow

As the activity and innovation surrounding token-based network models continue to grow, builders are wondering how to differentiate between different types of tokens—and which type of token might be the best fit for their business. Meanwhile, consumers and policymakers are striving to better understand the role and risks of blockchain tokens in applications.

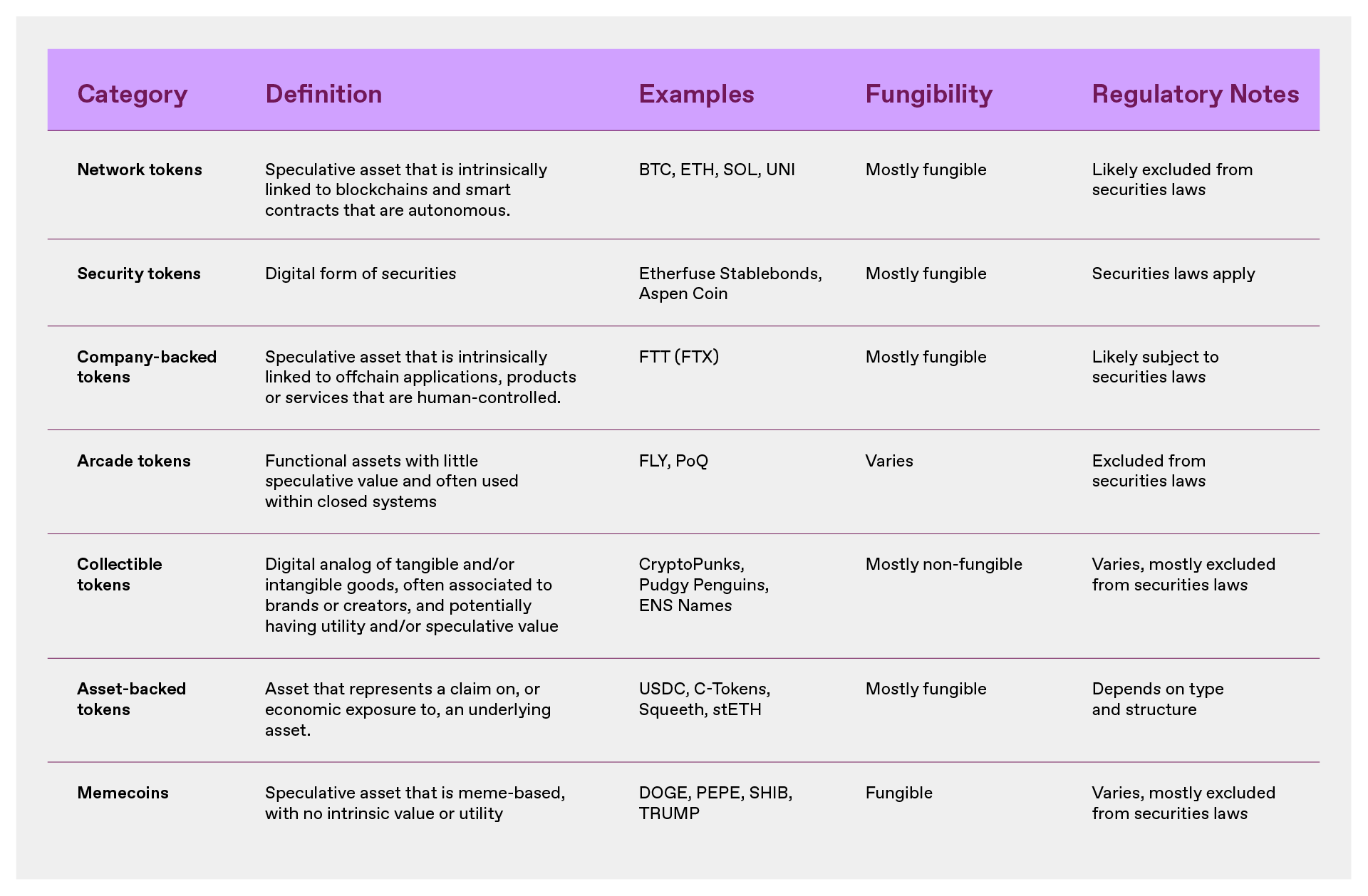

To facilitate organizational discussions, we provide definitions, examples, and frameworks to help you understand the seven types of tokens most commonly used by entrepreneurs: Network Tokens, Security Tokens, Company-Supported Tokens, Utility Tokens, Collectible Tokens, Asset-Backed Tokens, and Memecoins. We outline them in more detail below.

Quick Review: Tokens and Their Characteristics

Fundamentally, tokens enable true digital ownership.

More precisely, a blockchain is a decentralized computer made up of a network of individual computers that maintain a shared ledger—essentially a “cloud computer”. Tokens are data records on these ledgers that can track quantities, permissions, and other metadata. Crucially, these data records can only be altered according to the rules encoded on the blockchain, which can be used to grant enforceable rights.

Beneath this precision, many details affect design, functionality, value, and risk: because tokens are embedded in software, they can be programmed to represent almost anything—any digital form or property record. This means tokens can be designed as digital stores of value, like Bitcoin, productive and consumable assets, like Ethereum, collectibles, like digital trading cards and game items, payment stablecoins, like USDC, and even digitized stocks.

Some tokens provide holders with various rights (such as voting rights or economic rights), while others only allow for the use of products or network services. Some tokens can be transferred between users, while others cannot. Some tokens are fungible, meaning all units are equivalent (like dollar bills), while others are non-fungible, meaning they represent unique individual assets (one-of-a-kind, like trading cards, or even the Mona Lisa).

These design choices are important because they determine whether a token is a good store of value or medium of exchange; whether it is a productive asset with intrinsic functionality and/or economic value; or whether it is essentially worthless. The characteristics of a specific token also determine how it will be treated under applicable law.

Therefore, whether you are building a blockchain-based project, investing in tokens, or simply using tokens as a consumer, it is crucial to understand what to look for. It is important not to confuse Memecoins with Network Tokens. The remainder of this article aims to help clarify this confusion.

Types of Tokens

Network Tokens

Network tokens are fundamentally tied to the programmatic functionality of a blockchain or smart contract protocol, and their value derives from this.

Network tokens typically have built-in utility; they can be used for network operations, achieving consensus, coordinating protocol upgrades, or incentivizing network actions. The networks associated with these tokens usually (in most cases should) contain economic mechanisms that drive token value. These include programmatic buybacks, dividends, and other changes to the total supply of tokens through creation (“faucets”) or destruction (“sinks”) to introduce inflation and deflationary pressures to serve the network.

Network tokens can have trust dependencies similar to commodities and securities. Recognizing this, the SEC's 2019 framework and FIT21 stipulate that network tokens will be excluded from U.S. securities laws when the underlying network's decentralization mitigates these trust dependencies. The core essence of decentralization is that the system can operate without human control (by individuals, companies, or management teams).

Network tokens are best suited for bootstrapping the creation of new networks, allocating ownership or control of the network to its users, and/or ensuring the network can self-fund for sustainable and secure operations. Examples of network tokens include DOGE, Bitcoin's BTC, Ethereum's ETH, Solana's SOL, and Uniswap's UNI. In the context of smart contract protocols like Uniswap and Aave, network tokens are sometimes referred to as “protocol tokens” or “application tokens”.

Security Tokens

Security tokens represent the digital form of securities, which can be traditional forms (like company stocks or corporate bonds) or have special characteristics, such as providing profit interests in limited liability companies, shares of athletes' future earnings, or even the securitized rights to future litigation settlement payments.

Securities typically grant holders certain rights, ownership, or interests, and their issuers often have unilateral power to affect or construct asset risk. As the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is expected to modernize securities laws to allow on-chain trading, the number and types of tokenized securities may increase, potentially enhancing the efficiency and liquidity of the securities market. However, even as categories continue to grow, digital securities will still be subject to U.S. securities laws.

Security tokens have been used to raise funds for commercial enterprises. Examples of security tokens include Etherfuse Stablebonds and Aspen Coin, the latter representing a fractional ownership interest in the Aspen Ridge Resort.

Company-Supported Tokens

Company-supported tokens are intrinsically linked to applications, products, or services operated by a company (or other centralized organization) and derive value from them.

Like network tokens, company-supported tokens may utilize blockchain and smart contracts (for example, to facilitate payments). However, because they are primarily related to off-chain operations rather than network ownership, companies can unilaterally control their issuance, utility, and value. Like utility tokens (described below), company-supported tokens typically have their own embedded utility. Unlike utility tokens, company-supported tokens have speculative characteristics.

Given these characteristics—although company-supported tokens do not grant holders explicit rights, ownership, or interests like traditional securities—they have trust dependencies similar to securities: their value essentially depends on a system controlled by individuals, companies, or management teams. Therefore, while company-supported tokens themselves are not securities, their trading may be subject to U.S. securities laws when they attract investment.

Company-supported tokens may become a legitimate category. However, they have historically been used in the U.S. to illegally circumvent securities laws—attracting investment in applications, products, or services controlled by the company, potentially acting as proxies for equity or profit interests in the company. Examples of company-supported tokens include FTT, which acts as a profit interest in the FTX exchange, or a hypothetical cloud service provider issuing tokens that allow holders to access cloud services and receive a portion of on-chain revenue from such services. Meanwhile, BNB is an example of a company-supported token that evolved into a network token with the launch of Binance Smart Chain. Company-supported tokens are sometimes referred to as “startup tokens” or, given their link to off-chain applications, “application tokens.”

For more information on the differences between network tokens and company-supported tokens (including FTT), please read “Network Tokens vs. Company-Backed Tokens.”

Utility Tokens

Utility tokens provide utility within a system and are not intended for investment purposes. Utility tokens are often used as currency in the digital economy. For example, digital gold in games, loyalty points in membership programs, or points redeemable for digital products and services.

Importantly, utility tokens differ from security tokens, network tokens, and company-supported tokens because they are specifically designed to prevent speculation. For instance, these tokens may have no supply cap (meaning an unlimited number can be minted) and/or limited transferability; they may expire or depreciate if not used, or they may only have monetary value and utility within the system that issues them. Most importantly, they do not provide, promise, or imply financial returns. Given that they are not suitable as investment products, utility tokens are generally not subject to U.S. securities laws.

Utility tokens are best suited to serve as currency in the digital economy, where issuers gain economic benefits by controlling the monetary policy of that digital economy (acting as a central bank) and maintaining stable token value, rather than profiting from token value appreciation. Examples include FLY, which is the loyalty and payment token for the Blackbird restaurant network. Another example is Pocketful of Quarters, an in-game asset that did not receive action relief from the SEC in 2019. Robux and Start Alliance Points have not yet been tokenized, but they exemplify the concept of utility tokens well. Utility tokens are sometimes referred to as “utility** tokens,” “loyalty tokens,” or “points**.”

Collectible Tokens

The value, utility, or significance of collectible tokens derives from the record of ownership of tangible or intangible goods. For example, collectible tokens can be digital representations or embodiments of artwork, music, or literary works; collectibles or goods, such as concert ticket stubs; memberships in clubs or communities; or assets in games or the metaverse, such as digital swords or plots of metaverse land.

These tokens are typically non-fungible and often have utility. For instance, collectible tokens can serve as event permits or tickets; they can be used in video games (like that sword); or they can provide ownership related to intellectual property rights. Because collectible tokens are often associated with finished products or goods and do not rely on third-party efforts, they are generally not subject to U.S. securities laws.

Collectible tokens are best suited for conveying ownership of tangible or intangible goods. Many (though not all) “NFT” products fall into this category. Examples include NFTs that convey ownership of digital art or other media; profile pictures (or “pfps”) like CryptoPunks and Bored Apes, as well as other virtual fashion and branded goods; game items; and account records or identifiers (such as ENS domains).

Some collectible tokens are directly associated with physical products, either providing a digital extension of the experience of physical products, such as Pudgy Penguins toys and Generative Goods trading cards; or providing a digital representation of physical goods for easier tracking and/or exchange, such as NFT event tickets and BAXUS's vaulted liquor NFTs.

Asset-Backed Tokens

The value of asset-backed tokens derives from claims or economic risks associated with one or more underlying assets. These underlying assets may include real-world assets (such as commodities, fiat currencies, or securities) or digital assets (such as cryptocurrencies or liquidity pool interests).

Asset-backed tokens can be fully or partially collateralized and can serve various purposes: acting as a store of value, hedging tools, or on-chain financial primitives. Unlike collectible tokens that derive value from ownership of unique items (like digital artworks, in-game items, or event tickets), asset-backed tokens function more like financial instruments, deriving value from their collateral, price peg mechanisms, or redemption rights. However, the regulatory treatment of asset-backed tokens depends on their structure and use. Some tokens, such as fiat-backed stablecoins, are generally not subject to U.S. securities laws. Other tokens, such as certain derivative tokens, may be subject to securities or commodities regulation if they represent investment contracts or similar futures-like instruments.

Asset-backed tokens have many use cases, including:

Stablecoins, pegged to currencies or assets;

Derivative tokens, providing synthetic exposure to underlying assets or financial positions;

Liquidity Provider (LP) tokens, representing claims on pooled assets in decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols;

Deposit Receipt tokens, representing staked or custodial assets.

Examples include USDC (a fiat-backed stablecoin), Compound's C tokens (an LP token), Lido's stETH (a liquid staking token), and OPYN's Squeeth (a derivative token tracking ETH prices).

Memecoins

Memecoins are tokens that lack intrinsic utility or value, often associated with internet memes or community-driven movements, and have no fundamental connection to a network, company, or application.

The price of memecoins is entirely driven by speculation and related market forces, making them highly susceptible to manipulation. Their main characteristics are a lack of intrinsic purpose (if they have a purpose, they are no longer memecoins), a lack of utility, and the resulting zero-sum nature and volatility. Memecoins are generally not subject to U.S. securities laws, but they are still subject to anti-fraud and market manipulation laws.

Examples include PEPE, SHIB, and TRUMP.

Not all tokens fit perfectly into one of these categories—entrepreneurs regularly iterate and experiment with new models. For instance, if social and reputation tokens are non-investable, they may resemble utility tokens more closely, while if they are controlled by centralized issuers, they may resemble company-supported tokens more closely. As token characteristics change or new functionalities are added, tokens can also evolve from one category to another, making classification challenging.

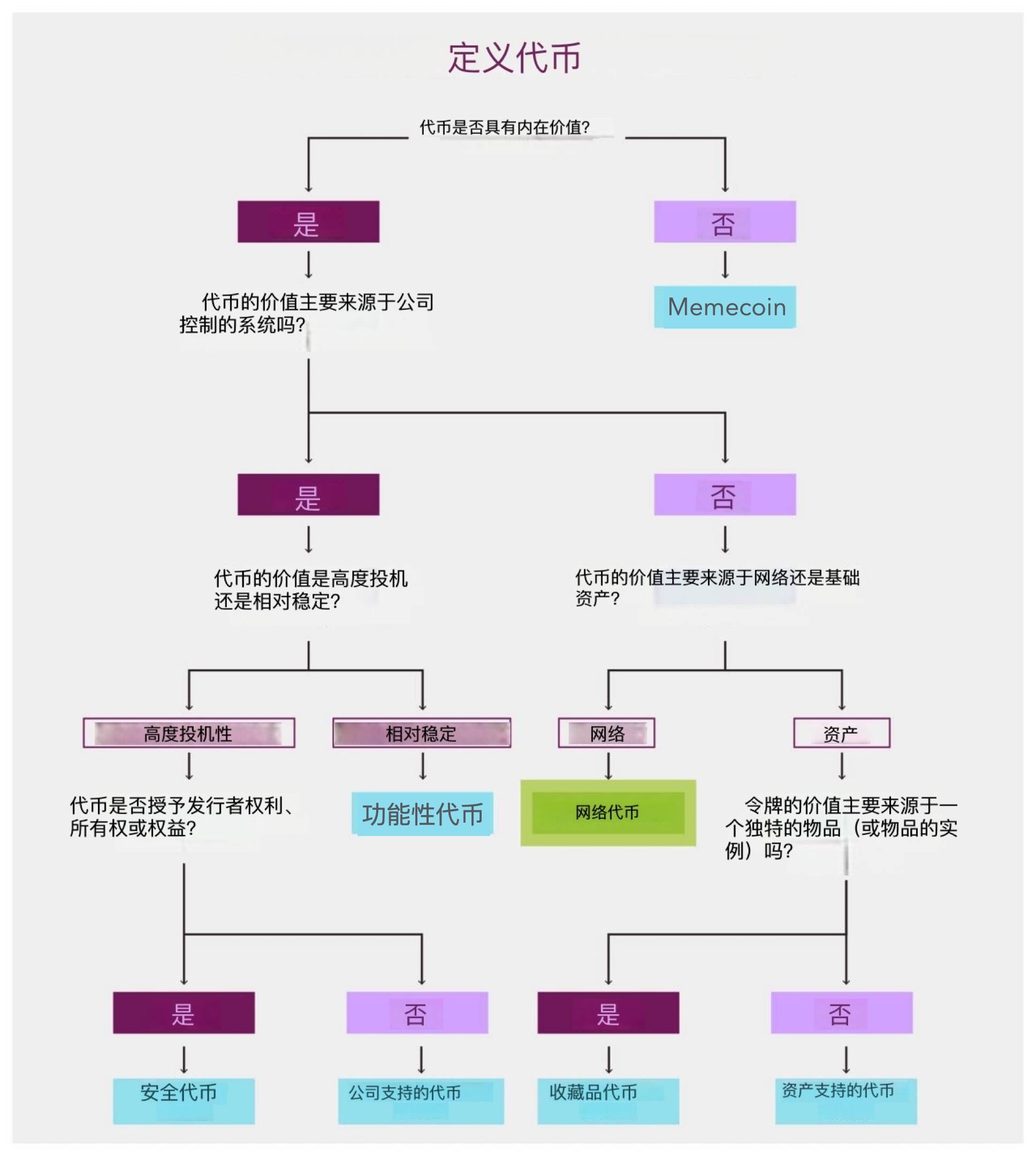

But the decisive characteristic that delineates these categories is the expected source of value accumulation. A flowchart helps illustrate this:

(Note: The images are AI translations and may differ somewhat from the original definitions of tokens.)

Acknowledgments: We thank Chris Dixon, Tim Roughgarden, and Bill Hinman for their helpful comments; and Tim Sullivan for his editing.

Miles Jennings is the General Counsel of a16z crypto, responsible for providing advice on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs, and state and federal securities laws for the firm and its portfolio companies.

Scott Duke Kominers is the Sarofim-Rock Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, an Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at Harvard University, and a research partner at a16z crypto. He also advises several companies on web3 strategy as well as market and incentive design; for further disclosures, please see his website. He is also a co-author of the book “Everything Token: How NFTs and Web3 Will Change the Way We Buy, Sell, and Create”.

Eddy Lazzarin is the Chief Technology Officer at a16z crypto. He is responsible for managing the engineering, research, and security teams that support the investment process and work with portfolio companies to build the future of the internet.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。