Stay vigilant in the face of an endless stream of scams, and take necessary precautions in a timely manner to protect your asset security.

Author: CertiK

Introduction

In the Web3 world, new tokens are constantly emerging. Have you ever wondered how many new tokens are issued every day? Are these new tokens safe?

These questions are not unfounded. In the past few months, the CertiK security team has captured a large number of Rug Pull transaction cases. Notably, all the tokens involved in these cases are newly launched tokens that have just been added to the blockchain.

Subsequently, CertiK conducted an in-depth investigation into these Rug Pull cases and discovered the existence of organized criminal groups behind them, summarizing the patterned characteristics of these scams. Through a thorough analysis of the methods used by these groups, CertiK identified a possible promotional channel for Rug Pull scams: Telegram groups. These groups utilize the "New Token Tracer" feature in groups like Banana Gun and Unibot to attract users to purchase scam tokens and ultimately profit through Rug Pulls.

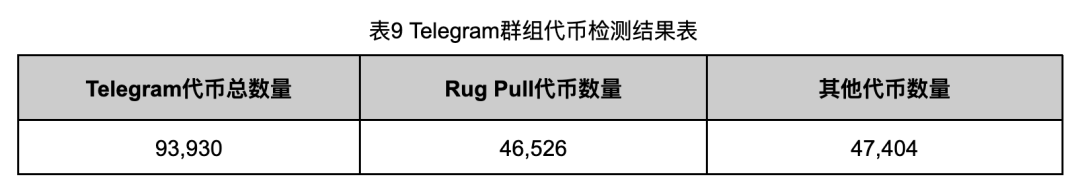

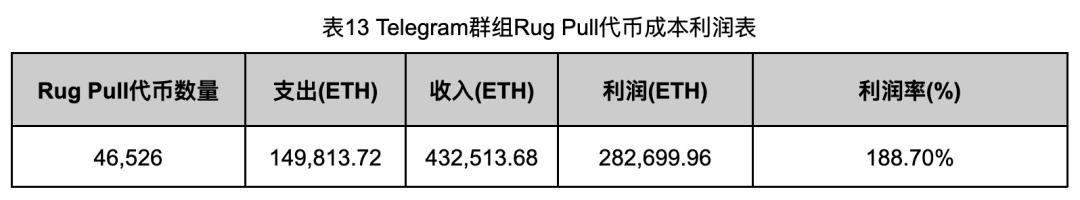

CertiK compiled data on token push notifications from these Telegram groups from November 2023 to early August 2024, finding a total of 93,930 new tokens pushed, of which 46,526 tokens were involved in Rug Pulls, accounting for a staggering 49.53%. It is estimated that the cumulative investment cost behind these Rug Pull tokens was 149,813.72 ETH, with a profit of 282,699.96 ETH at a return rate of up to 188.7%, equivalent to about $800 million.

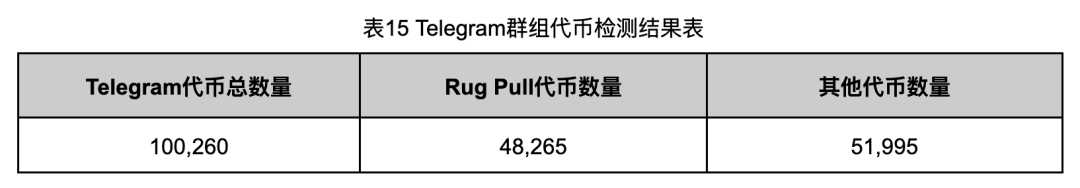

To assess the proportion of new tokens pushed by Telegram groups on the Ethereum mainnet, CertiK compiled data on new tokens issued on the Ethereum mainnet during the same period. The data shows that a total of 100,260 new tokens were issued, with tokens pushed through Telegram groups accounting for 89.99% of the mainnet. On average, about 370 new tokens are born each day, far exceeding reasonable expectations. After continuous in-depth investigation, we found an unsettling truth—at least 48,265 tokens are involved in Rug Pull scams, accounting for as much as 48.14%. In other words, nearly one in every two new tokens on the Ethereum mainnet is involved in scams.

Additionally, CertiK has discovered more Rug Pull cases on other blockchain networks. This means that not only is the security situation on the Ethereum mainnet severe, but the entire Web3 ecosystem of newly issued tokens is far more dire than expected. Therefore, CertiK has written this research report in hopes of helping all Web3 members raise their awareness of prevention, remain vigilant in the face of an endless stream of scams, and take necessary precautions in a timely manner to protect their asset security.

ERC-20 Tokens

Before officially starting this report, let's first understand some basic concepts.

ERC-20 tokens are one of the most common token standards on the blockchain today, defining a set of specifications that allow tokens to interoperate between different smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps). The ERC-20 standard specifies the basic functions of tokens, such as transferring, querying balances, and authorizing third parties to manage tokens. Due to this standardized protocol, developers can more easily issue and manage tokens, simplifying the creation and use of tokens. In fact, any individual or organization can issue their own tokens based on the ERC-20 standard and raise startup funds for various financial projects through token presales. Because of the widespread use of ERC-20 tokens, they have become the foundation for many ICOs and decentralized finance projects.

Familiar tokens like USDT, PEPE, and DOGE are all ERC-20 tokens, which users can purchase through decentralized exchanges. However, some scam groups may also issue malicious ERC-20 tokens with backdoor codes, list them on decentralized exchanges, and then lure users into purchasing them.

Typical Scam Cases of Rug Pull Tokens

Here, we will use a scam case involving a Rug Pull token to gain a deeper understanding of the operational model of malicious token scams. It is important to clarify that a Rug Pull refers to a fraudulent act where project parties suddenly withdraw funds or abandon the project in decentralized finance projects, resulting in significant losses for investors. Rug Pull tokens are specifically issued to carry out such fraudulent activities.

The Rug Pull tokens mentioned in this article are sometimes referred to as "Honey Pot tokens" or "Exit Scam tokens," but we will uniformly refer to them as Rug Pull tokens in the following text.

· Case

The attacker (Rug Pull group) deployed the TOMMI token using the Deployer address (0x4bAF), then created a liquidity pool with 1.5 ETH and 100,000,000 TOMMI tokens, actively purchasing TOMMI tokens through other addresses to fake the trading volume of the liquidity pool to attract users and on-chain new token bots to buy TOMMI tokens. After a certain number of new token bots were deceived, the attacker executed the Rug Pull using the Rug Puller address (0x43a9), where the Rug Puller dumped 38,739,354 TOMMI tokens into the liquidity pool, exchanging them for about 3.95 ETH. The tokens of the Rug Puller came from malicious approval granted by the TOMMI token contract, which allowed the Rug Puller to directly withdraw TOMMI tokens from the liquidity pool and then carry out the Rug Pull.

· Related Addresses

Deployer: 0x4bAFd8c32D9a8585af0bb6872482a76150F528b7

TOMMI Token: 0xe52bDD1fc98cD6c0cd544c0187129c20D4545C7F

Rug Puller: 0x43A905f4BF396269e5C559a01C691dF5CbD25a2b

User disguised as Rug Puller (one of them): 0x4027F4daBFBB616A8dCb19bb225B3cF17879c9A8

Rug Pull fund transfer address: 0x1d3970677aa2324E4822b293e500220958d493d0

Rug Pull fund retention address: 0x28367D2656434b928a6799E0B091045e2ee84722

· Related Transactions

Deployer obtains startup funds from a centralized exchange: 0x428262fb31b1378ea872a59528d3277a292efe7528d9ffa2bd926f8bd4129457

Deploying TOMMI token: 0xf0389c0fa44f74bca24bc9d53710b21f1c4c8c5fba5b2ebf5a8adfa9b2d851f8

Creating liquidity pool: 0x59bb8b69ca3fe2b3bb52825c7a96bf5f92c4dc2a8b9af3a2f1dddda0a79ee78c

Fund transfer address sends funds to disguised user (one of them): 0x972942e97e4952382d4604227ce7b849b9360ba5213f2de6edabb35ebbd20eff

Disguised user purchases tokens (one of them): 0x814247c4f4362dc15e75c0167efaec8e3a5001ddbda6bc4ace6bd7c451a0b231

Rug Pull: 0xfc2a8e4f192397471ae0eae826dac580d03bcdfcb929c7423e174d1919e1ba9c

Rug Pull sends the proceeds to the transfer address: 0xf1e789f32b19089ccf3d0b9f7f4779eb00e724bb779d691f19a4a19d6fd15523

Transfer address sends funds to the retention address: 0xb78cba313021ab060bd1c8b024198a2e5e1abc458ef9070c0d11688506b7e8d7

· Rug Pull Process

- Prepare attack funds.

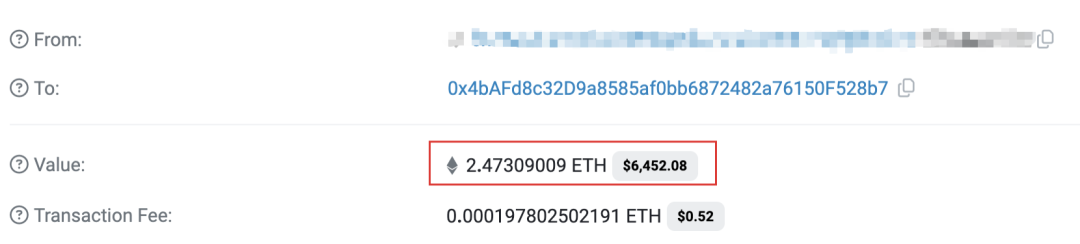

The attacker deposits 2.47309009 ETH into the Token Deployer (0x4bAF) through a centralized exchange as startup funds for the Rug Pull.

Figure 1 Deployer obtains startup fund transaction information

- Deploy the backdoored Rug Pull token.

The Deployer creates the TOMMI token, pre-mining 100,000,000 tokens and allocating them to itself.

Figure 2 Deployer creates TOMMI token transaction information

- Create the initial liquidity pool.

The Deployer creates a liquidity pool with 1.5 ETH and all pre-mined tokens, obtaining about 0.387 LP tokens.

Figure 3 Deployer creates liquidity pool transaction fund flow

- Destroy all pre-mined token supply.

The Token Deployer sends all LP tokens to the zero address for destruction. Since the TOMMI contract does not have a Mint function, the Token Deployer has theoretically lost the ability to execute a Rug Pull at this point. (This is also one of the necessary conditions to attract new token bots to enter; some new token bots will assess whether the newly added tokens in the pool have Rug Pull risks. The Deployer also sets the contract's Owner to the zero address to deceive the anti-fraud programs of new token bots).

Figure 4 Deployer destroys LP token transaction information

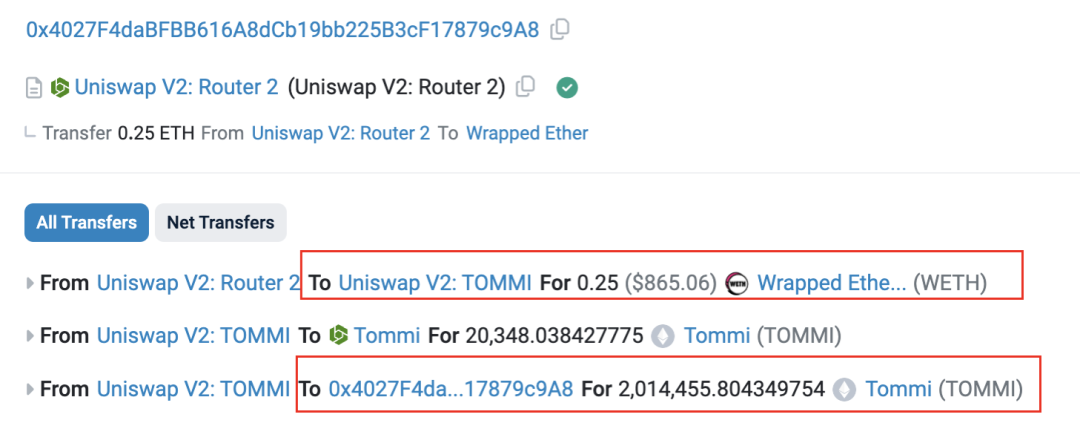

- Faking trading volume.

The attacker actively purchases TOMMI tokens from the liquidity pool using multiple addresses, inflating the trading volume of the pool to further attract new token bots (the basis for determining that these addresses are disguised by the attacker: the funds of the related addresses come from the historical fund transfer addresses of the Rug Pull group).

Figure 5 Transaction information and fund flow of the attacker purchasing TOMMI tokens from other addresses

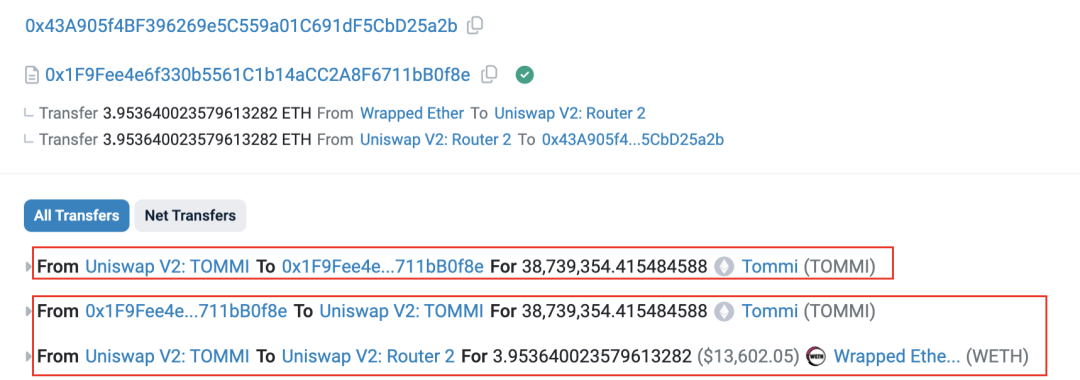

- The attacker initiates the Rug Pull through the Rug Puller address (0x43A9), directly transferring 38,739,354 tokens from the liquidity pool through the token's backdoor, and then dumps these tokens into the pool, extracting about 3.95 ETH.

Figure 6 Rug Pull transaction information and fund flow

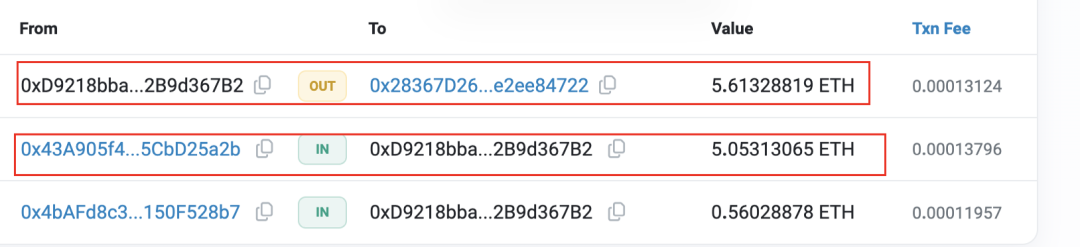

- The attacker sends the funds obtained from the Rug Pull to the transfer address 0xD921.

Figure 7 Rug Puller sends attack proceeds to the transfer address transaction information

- The transfer address 0xD921 sends the funds to the fund retention address 0x2836. From this, we can see that after the Rug Pull is completed, the Rug Puller sends the funds to a certain fund retention address. The fund retention address is where we have monitored a large number of Rug Pull cases' funds being aggregated, and the fund retention address will split most of the received funds to start a new round of Rug Pulls, while a small portion of the funds will be withdrawn through centralized exchanges. We have identified several fund retention addresses, with 0x2836 being one of them.

Figure 8 Fund transfer information of the transfer address

· Rug Pull Code Backdoor

Although the attacker has attempted to prove to the outside world that they cannot execute a Rug Pull by destroying the LP tokens, in reality, the attacker has left a malicious approve backdoor in the openTrading function of the TOMMI token contract. This backdoor allows the liquidity pool to approve the transfer rights of tokens to the Rug Puller address when creating the liquidity pool, enabling the Rug Puller address to directly withdraw tokens from the liquidity pool.

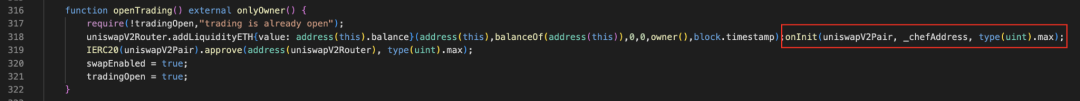

Figure 9 openTrading function in the TOMMI token contract

Figure 10 onInit function in the TOMMI token contract

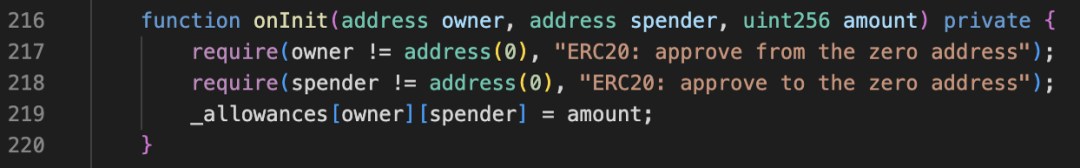

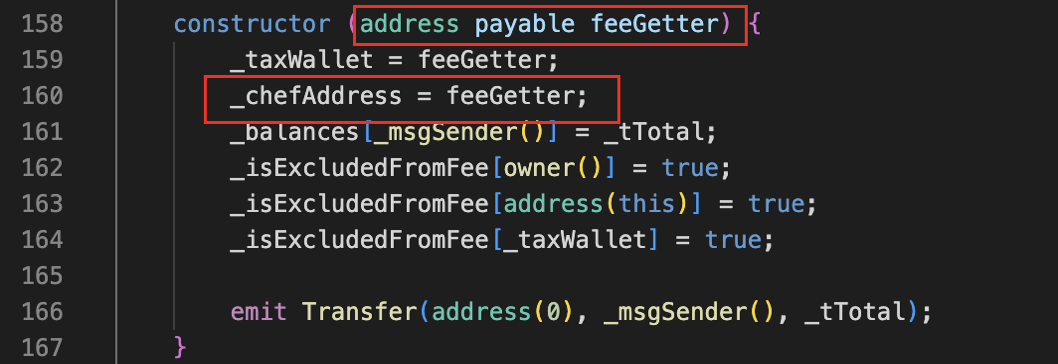

The implementation of the openTrading function is shown in Figure 9, whose main function is to create a new liquidity pool. However, the attacker calls the backdoor function onInit (shown in Figure 10) within this function, allowing uniswapV2Pair to approve the transfer rights of tokens to the _chefAddress address for the amount of type(uint256). Here, uniswapV2Pair is the liquidity pool address, and _chefAddress is the Rug Puller address, which is specified during contract deployment (shown in Figure 11).

Figure 11 Constructor in the TOMMI token contract

· Patterned Modus Operandi

By analyzing the TOMMI case, we can summarize the following four characteristics:

The Deployer obtains funds through centralized exchanges: The attacker first provides a source of funds for the deployer address (Deployer) through a centralized exchange.

The Deployer creates a liquidity pool and destroys LP tokens: After creating the Rug Pull token, the deployer immediately creates a liquidity pool for it and destroys the LP tokens to increase the project's credibility and attract more investors.

The Rug Puller exchanges a large number of tokens for ETH in the liquidity pool: The Rug Pull address (Rug Puller) uses a large number of tokens (usually far exceeding the total supply of the token) to exchange for ETH in the liquidity pool. In other cases, the Rug Puller has also removed liquidity to obtain ETH from the pool.

The Rug Puller transfers the ETH obtained from the Rug Pull to the fund retention address: The Rug Puller transfers the obtained ETH to the fund retention address, sometimes through an intermediary address.

These characteristics are commonly found in the cases we have captured, indicating that Rug Pull behavior has obvious patterned features. Additionally, after completing a Rug Pull, the funds are usually aggregated into a fund retention address, suggesting that these seemingly independent Rug Pull cases may involve the same group or even the same scam organization.

Based on these characteristics, we extracted a behavioral pattern of Rug Pulls and used this pattern to scan and detect monitored cases, aiming to construct a possible profile of the scam group.

Rug Pull Scam Groups

· Mining Fund Retention Addresses

As mentioned earlier, Rug Pull cases typically aggregate funds into a fund retention address at the end. Based on this pattern, we selected several highly active fund retention addresses with clearly identifiable characteristics of associated cases for in-depth analysis.

A total of 7 fund retention addresses came into our view, which are associated with 1,124 Rug Pull cases successfully captured by our on-chain attack monitoring system (CertiK Alert). After successfully executing the scam, the Rug Pull group aggregates the illegal profits into these fund retention addresses. These fund retention addresses will split the accumulated funds for creating new tokens and manipulating liquidity pools in future Rug Pull scams. Additionally, a small portion of the accumulated funds is cashed out through centralized exchanges or swap platforms.

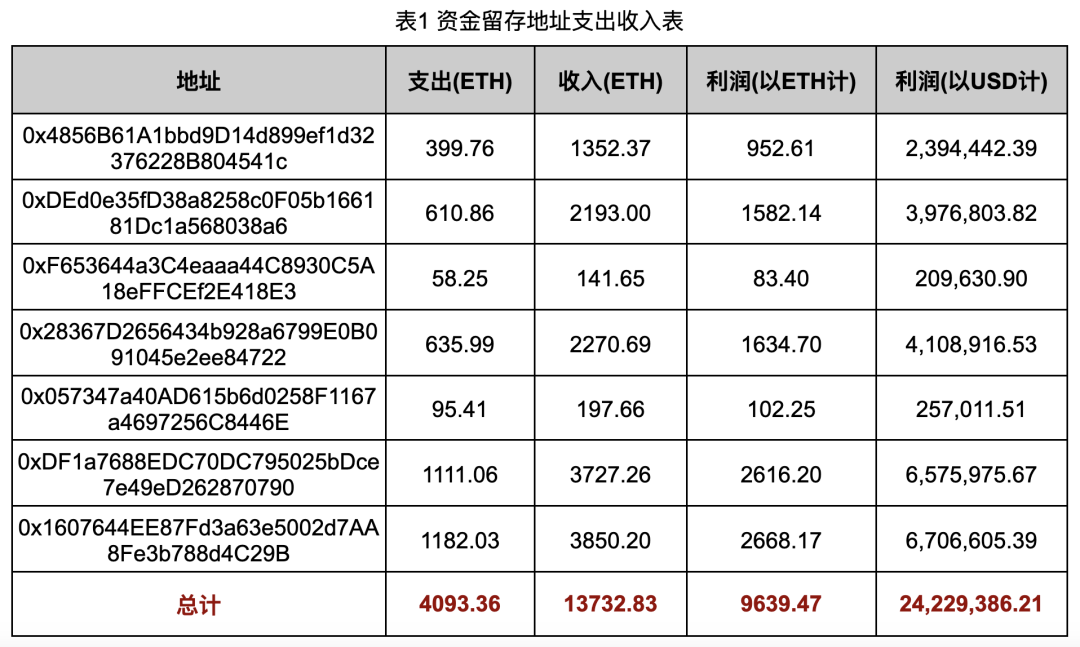

The statistical data on the funds of the fund retention addresses is shown in Table 1:

By calculating the costs and revenues of all Rug Pull scams in each fund retention address, we obtained the data in Table 1.

In a complete Rug Pull scam, the Rug Pull group typically uses one address as the deployer of the Rug Pull token (Deployer) and withdraws funds from a centralized exchange to obtain startup funds to create the Rug Pull token and the corresponding liquidity pool. Once a sufficient number of users or new token bots use ETH to purchase the Rug Pull token, the Rug Pull group will use another address as the Rug Pull executor (Rug Puller) to operate, transferring the obtained funds to the fund retention address.

In the above process, we consider the ETH obtained by the Deployer through the exchange or the ETH invested by the Deployer when creating the liquidity pool as the cost of the Rug Pull (the specific calculation depends on the Deployer's behavior). The ETH transferred to the fund retention address (or other transfer addresses) by the Rug Puller after completing the Rug Pull is regarded as the revenue from that Rug Pull, ultimately resulting in the data on revenue and expenditure in Table 1, where the ETH profit conversion used the ETH/USD price (1 ETH = 2,513.56 USD, price acquisition time was August 31, 2024), calculated at the real-time price during data integration.

It should be noted that the Rug Pull group also actively uses ETH to purchase the Rug Pull tokens they created to simulate normal liquidity pool activities, thereby attracting new token bots to purchase. However, this portion of the cost is not included in the calculation, so the data in Table 1 overestimates the actual profit of the Rug Pull group, and the real profit is relatively lower.

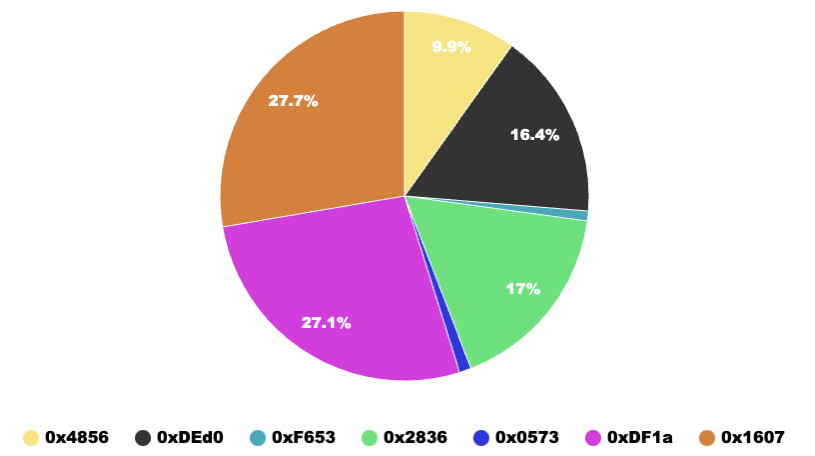

Figure 12 Pie chart of profit share from fund retention addresses

Using the profit data of each address from Table 1 to generate a profit share pie chart, as shown in Figure 12. The top three addresses in profit share ranking are 0x1607, 0xDF1a, and 0x2836. The address 0x1607 has the highest profit, approximately 2,668.17 ETH, accounting for 27.7% of the total profit of all addresses.

In fact, even if the final funds are aggregated into different fund retention addresses, due to the significant commonalities between the cases associated with these addresses (such as the implementation methods of Rug Pull backdoors, cash-out paths, etc.), we still highly suspect that these fund retention addresses may belong to the same group.

So, is there a possibility of some connection between these fund retention addresses?

· Mining Connections Between Fund Retention Addresses

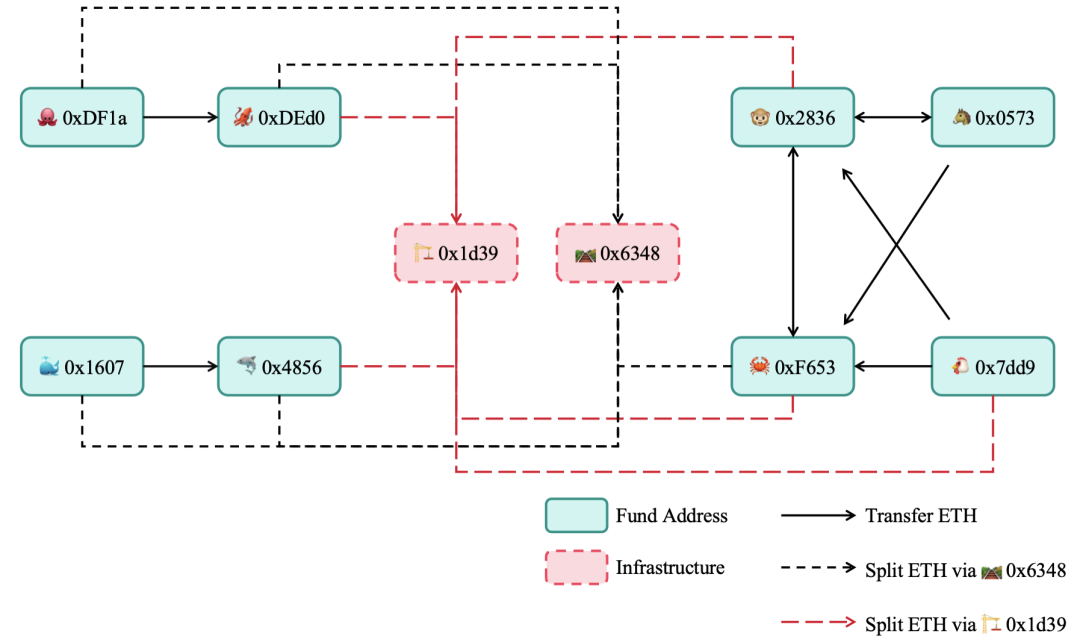

Figure 13 Fund flow diagram of fund retention addresses

An important indicator for determining whether there is a connection between fund retention addresses is to check if there are direct transfer relationships between these addresses. To verify the correlation between fund retention addresses, we crawled and analyzed the historical transaction records of these addresses.

In most cases we have analyzed in the past, the profits from each Rug Pull scam ultimately flow to a single fund retention address, making it impossible to associate different fund retention addresses by tracking the flow of profit funds. Therefore, we need to detect the fund flow situation between these fund retention addresses to obtain direct associations between them, and the detection results are shown in Figure 13.

It should be noted that the addresses 0x1d39 and 0x6348 in Figure 13 are shared Rug Pull infrastructure contract addresses among the fund retention addresses. The fund retention addresses use these two contracts to split funds and send them to other addresses, and these addresses that receive the split funds use them to fake the trading volume of Rug Pull tokens.

Based on the direct transfer relationships of ETH in Figure 13, we can categorize these fund retention addresses into three address sets:

0xDF1a and 0xDEd0;

0x1607 and 0x4856;

0x2836, 0x0573, 0xF653, and 0x7dd9.

There are direct transfer relationships within each address set, but there are no direct transfer activities between the sets. Therefore, it seems that these seven fund retention addresses can be divided into three different groups. However, these three address sets all use the same infrastructure contracts to split ETH for subsequent Rug Pull operations, which connects the seemingly loose three address sets into a whole. Thus, does this indicate that these fund retention addresses actually belong to the same group?

This question will not be discussed in depth here; readers can ponder the possibilities themselves.

· Mining Shared Infrastructure

The infrastructure addresses shared by the fund retention addresses mentioned earlier mainly include two:

0x1d3970677aa2324E4822b293e500220958d493d0 and 0x634847D6b650B9f442b3B582971f859E6e65eB53.

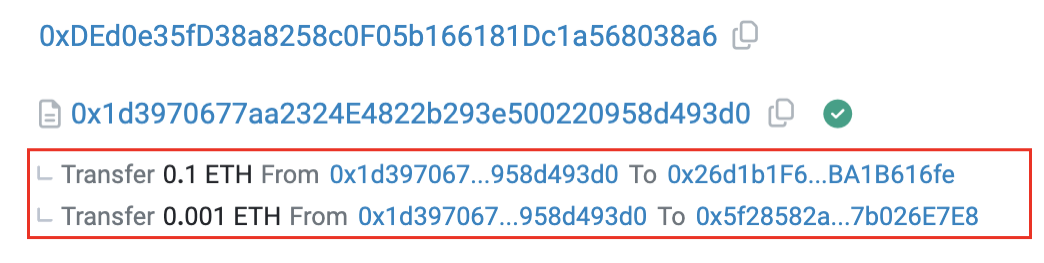

Among them, the infrastructure address 0x1d39 mainly contains two functional functions: "multiSendETH" and "0x7a860e7e". The main function of "multiSendETH" is to perform split transfers, where the fund retention addresses use the "Multi Send ETH" function of 0x1d39 to split part of the funds to multiple addresses to fake the trading volume of Rug Pull tokens, as shown in the transaction information in Figure 14.

This splitting operation helps the attackers fake the activity of the tokens, making them appear more attractive and thus enticing more users or new token bots to make purchases. Through this method, the Rug Pull group can further increase the deception and complexity of the scam.

Figure 14 Transaction information of fund retention addresses splitting funds through 0x1d39

The function of "0x7a860e7e" is used to purchase Rug Pull tokens. Other addresses disguised as ordinary users, after receiving the split funds from the fund retention addresses, either interact directly with Uniswap's Router to purchase Rug Pull tokens or use the "0x7a860e7e" function of 0x1d39 to purchase Rug Pull tokens to fake active trading volume.

The main functional functions of the infrastructure address 0x6348 are similar to those of 0x1d39, except that the function name for purchasing Rug Pull tokens is changed to "0x3f8a436c", which will not be elaborated on here.

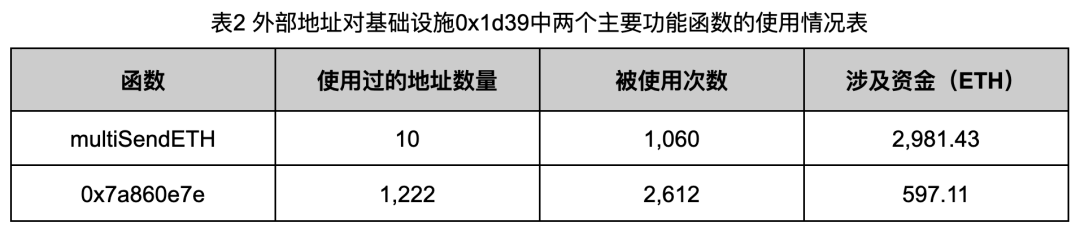

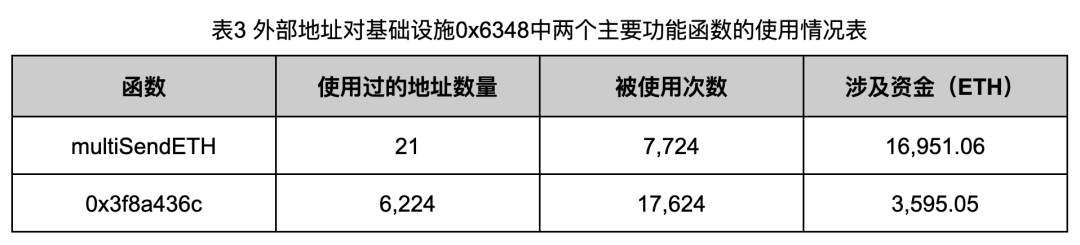

To further understand how the Rug Pull group uses these infrastructures, we crawled and analyzed the transaction history of 0x1d39 and 0x6348, counting the frequency of external addresses using the two functional functions in 0x1d39 and 0x6348, with the results shown in Tables 2 and 3.

From the data in Tables 2 and 3, it can be seen that the Rug Pull group has distinct characteristics in their use of infrastructure addresses: they only use a small number of fund retention addresses or transfer addresses to split funds, but they fake the trading volume of Rug Pull tokens through a large number of other addresses. For example, the number of addresses faking trading volume through address 0x6348 even reaches 6,224. Such a large number of addresses significantly increases the difficulty of distinguishing attacker addresses from victim addresses.

It should be particularly noted that the Rug Pull group’s method of faking trading volume is not limited to using these infrastructure addresses; some addresses also directly exchange tokens through exchanges to fake trading volume.

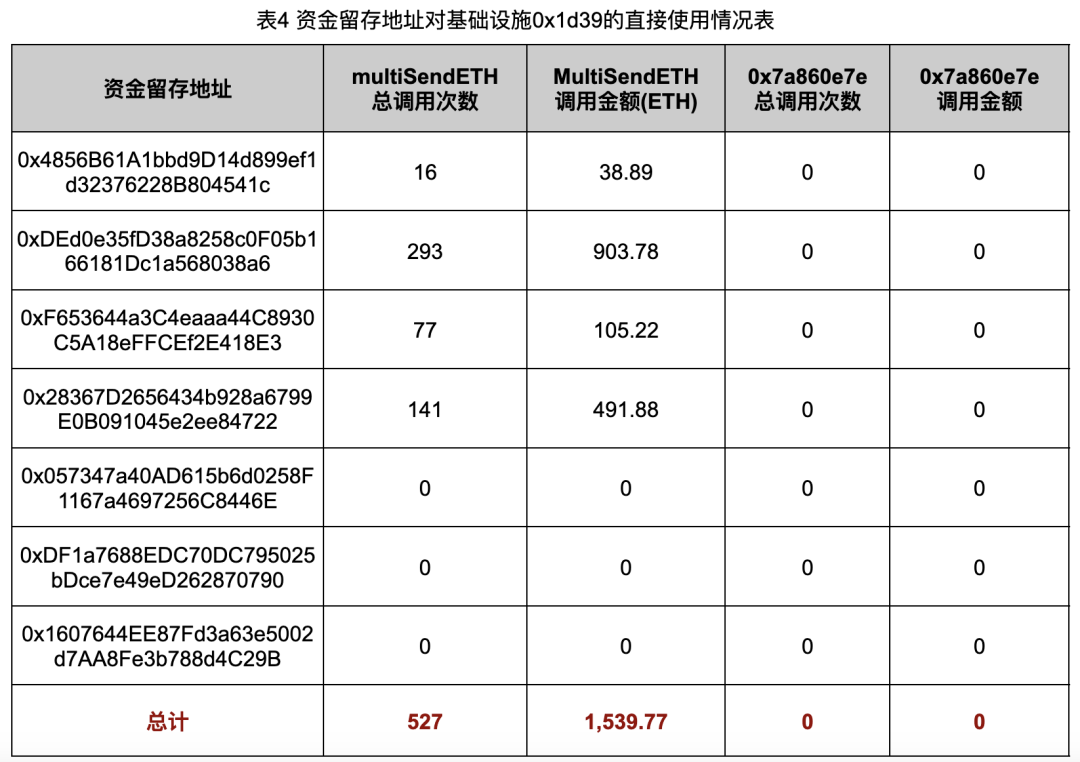

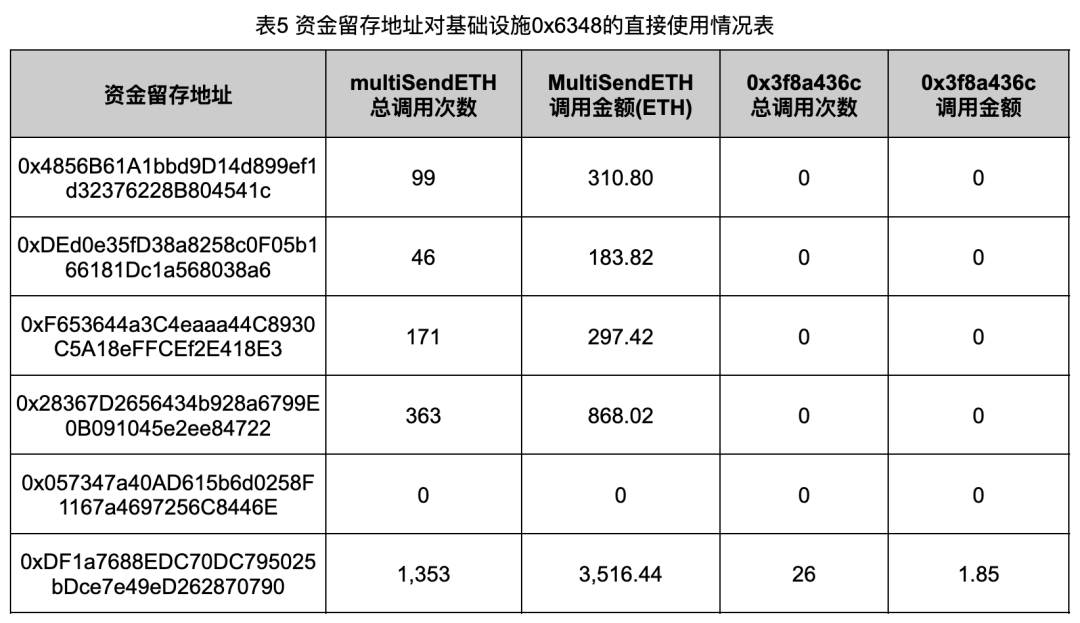

Additionally, we also counted the usage of the two functional functions in the addresses 0x1d39 and 0x6348 by the seven fund retention addresses mentioned earlier, as well as the amount of ETH involved in each function, with the final data shown in Tables 4 and 5.

From the data in Tables 4 and 5, it can be seen that the fund retention addresses have split funds a total of 3,616 times through the infrastructure, with a total amount reaching 9,369.98 ETH. Furthermore, except for address 0xDF1a, all fund retention addresses only performed split transfers through the infrastructure, while the operation of purchasing Rug Pull tokens was completed by the addresses receiving these split funds. This indicates that the Rug Pull groups have a clear strategy and defined roles in their operations.

Address 0x0573 did not split funds through the infrastructure; instead, the funds used to fake trading volume in its associated Rug Pull cases came from other addresses, indicating that there are certain differences in the operational styles of different fund retention addresses.

By analyzing the financial connections between different fund retention addresses and their use of infrastructure, we have gained a more comprehensive understanding of the associations between these fund retention addresses. The methods of these Rug Pull groups are more professional and standardized than we initially imagined, further indicating that a criminal organization is meticulously planning and operating everything behind the scenes to conduct systematic fraud activities.

· Mining Sources of Funds for Crimes

When conducting a Rug Pull, the Rug Pull group typically uses a new external account address (EOA) as the Deployer to deploy the Rug Pull token, and these Deployer addresses usually obtain startup funds through centralized exchanges or swap platforms. Therefore, we conducted a source of funds analysis on the Rug Pull cases associated with the fund retention addresses mentioned earlier, aiming to grasp more detailed information about the sources of funds for their crimes.

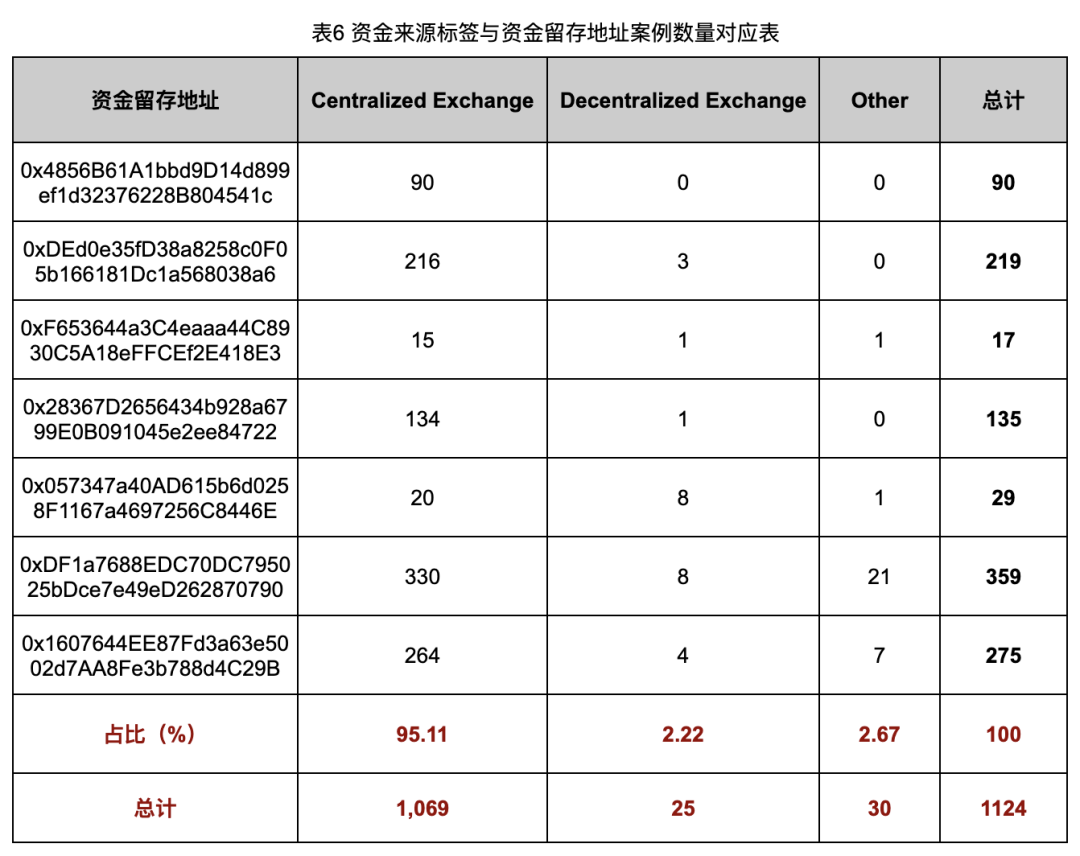

Table 6 shows the distribution of the number of funding source labels for the Deployer associated with the Rug Pull cases in each fund retention address.

From the data in Table 6, it can be seen that in the Rug Pull cases associated with each fund retention address, the Deployer funds for the Rug Pull tokens mostly come from centralized exchanges (CEX). Among all 1,124 Rug Pull cases we analyzed, the number of cases where the funds came from centralized exchange hot wallets reached 1,069, accounting for as high as 95.11%. This means that for the vast majority of Rug Pull cases, we can trace back to specific account holders through the KYC information and withdrawal history of centralized exchange accounts, thus obtaining key clues for solving the cases.

As we delved deeper, we found that these Rug Pull groups often obtain funds for their crimes simultaneously from multiple exchange hot wallets, and the usage levels (number of uses, proportions) of each wallet are roughly equivalent. This indicates that the Rug Pull groups intentionally increase the independence of each Rug Pull case in terms of fund flow, thereby raising the difficulty of tracing their origins and increasing the complexity of tracking.

Through detailed analysis of these fund retention addresses and Rug Pull cases, we can draw a profile of these Rug Pull groups: they are well-trained, have clear divisions of labor, are premeditated, and are well-organized. These characteristics demonstrate the high level of professionalism of the group and the systematic nature of their fraudulent activities.

Faced with such a tightly organized group of criminals, we cannot help but wonder and be curious about their promotional channels: how do these Rug Pull groups get users to discover and purchase these Rug Pull tokens? To answer this question, we began to focus on the victim addresses in these Rug Pull cases and attempted to reveal how these groups lure users into participating in their scams.

· Mining Victim Addresses

Through the analysis of financial connections, we maintained a list of addresses belonging to the Rug Pull groups and used it as a blacklist to filter out victim address sets from the trading records of the liquidity pools corresponding to the Rug Pull tokens.

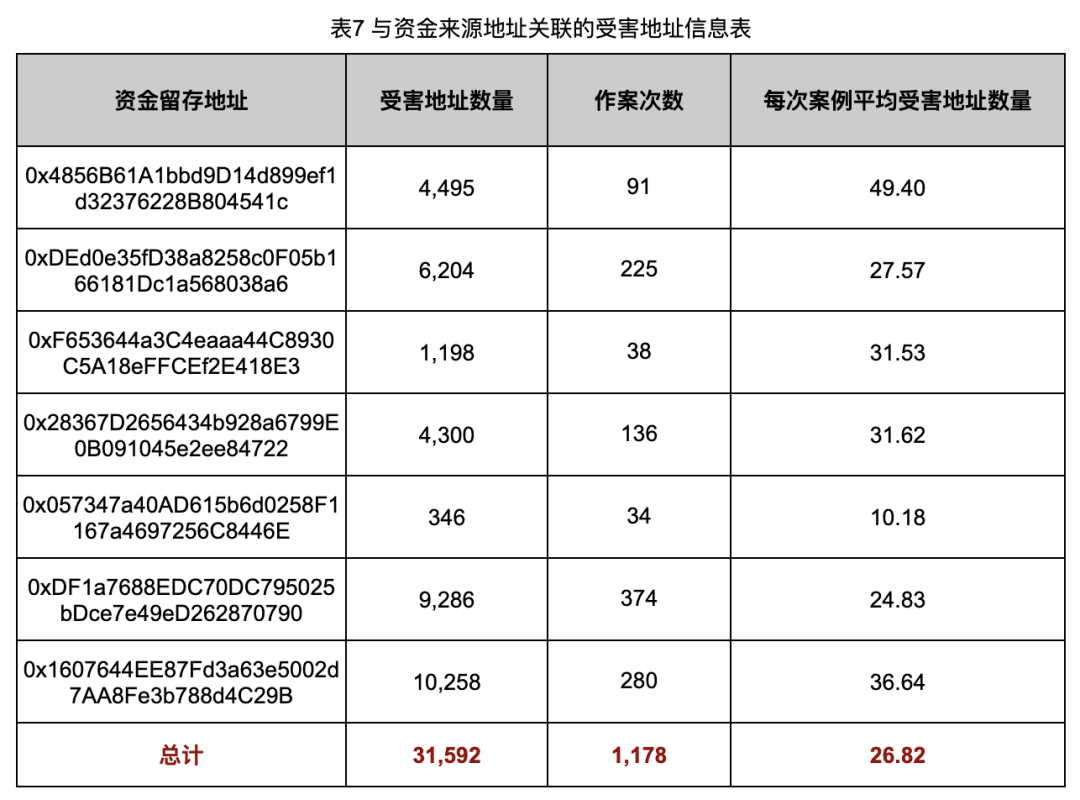

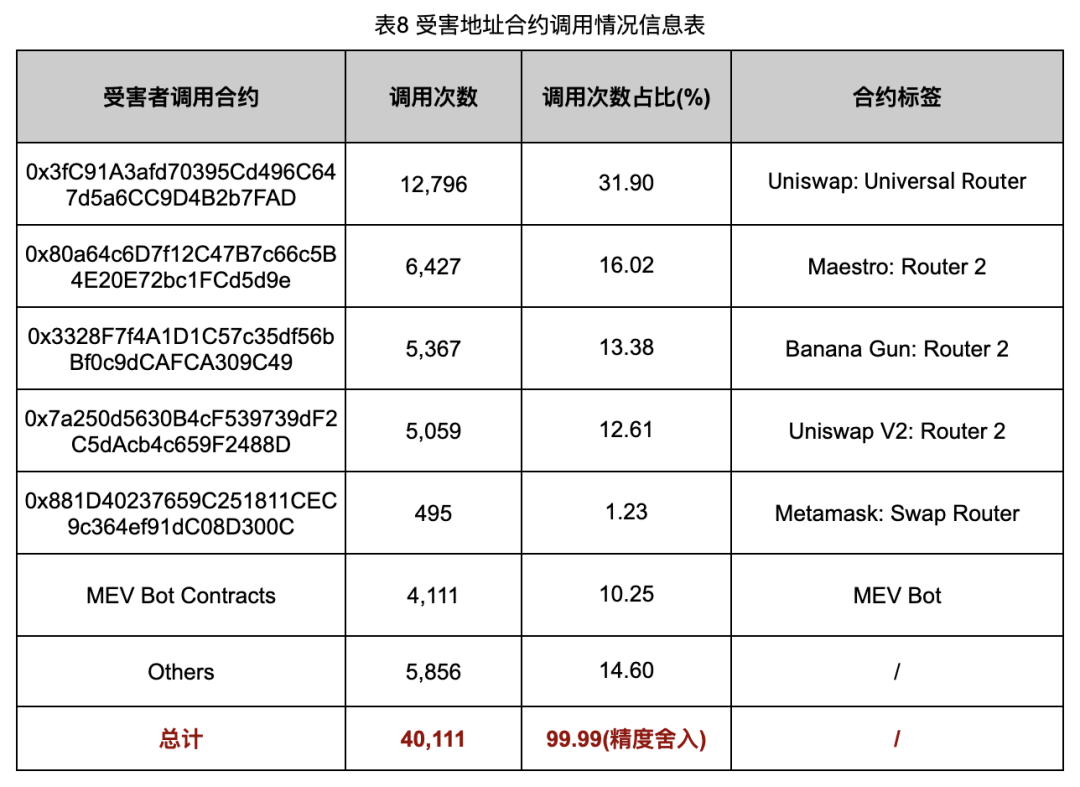

After analyzing these victim addresses, we obtained information about the victim addresses associated with the fund retention addresses (Table 7) and the contract call situation of the victim addresses (Table 8).

From the data in Table 7, it can be seen that in the Rug Pull cases captured by our on-chain monitoring system (CertiK Alert), the average number of victim addresses per case is 26.82. This number is actually higher than our initial expectations, which also means that the harm caused by these Rug Pull cases is greater than we previously imagined.

From the data in Table 8, it can be seen that among the contract calls for purchasing Rug Pull tokens by victim addresses, in addition to the more conventional purchasing methods through Uniswap and MetaMask Swap, 30.40% of Rug Pull tokens were purchased through well-known on-chain sniper bot platforms such as Maestro and Banana Gun.

This finding reminds us that on-chain sniper bots may be one of the important promotional channels for Rug Pull groups. Through these sniper bots, Rug Pull groups can quickly attract participants, especially those focused on new token launches. Therefore, we will focus on these on-chain sniper bots to further understand their role in Rug Pull scams and their promotional mechanisms.

Rug Pull Token Promotional Channels

We researched the current Web3 new token ecosystem, studied the operational models of on-chain sniper bots, and combined certain social engineering techniques to ultimately identify two potential advertising channels for Rug Pull groups: Twitter and Telegram groups.

It is important to emphasize that these Twitter and Telegram groups are not specifically created by Rug Pull groups but exist as fundamental components within the new token ecosystem. They are maintained by third-party organizations such as on-chain sniper bot operation teams or professional new token teams, specifically pushing newly launched tokens to new token participants. These groups have become a natural advertising avenue for Rug Pull groups, attracting users to purchase malicious tokens through the promotion of new tokens, thereby implementing scams.

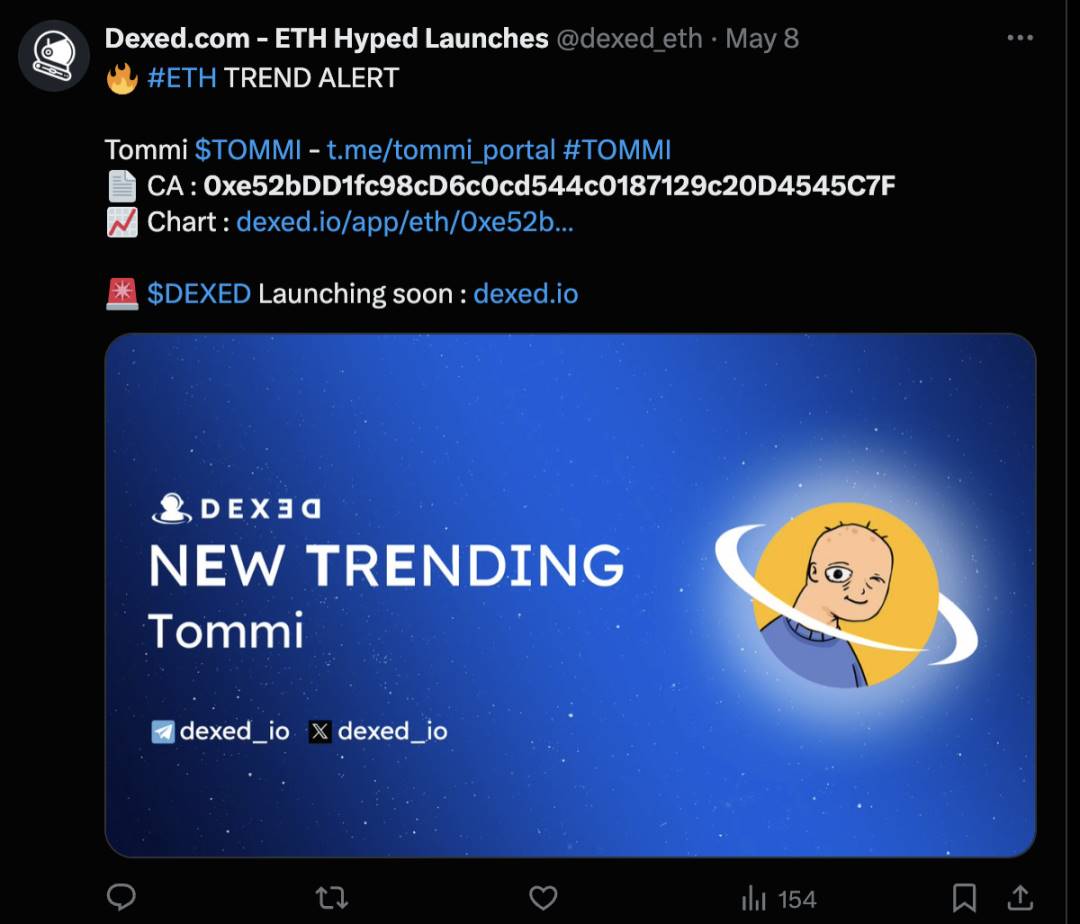

· Twitter Advertising

Figure 15 shows the Twitter advertisement for the TOMMI token mentioned earlier. It can be seen that the Rug Pull group utilized Dexed.com’s new token promotion service to expose their Rug Pull token to the public, attracting more victims. In our actual research, we found that a considerable number of Rug Pull tokens could be found with corresponding advertisements on Twitter, and these advertisements often came from different third-party organizations' Twitter accounts.

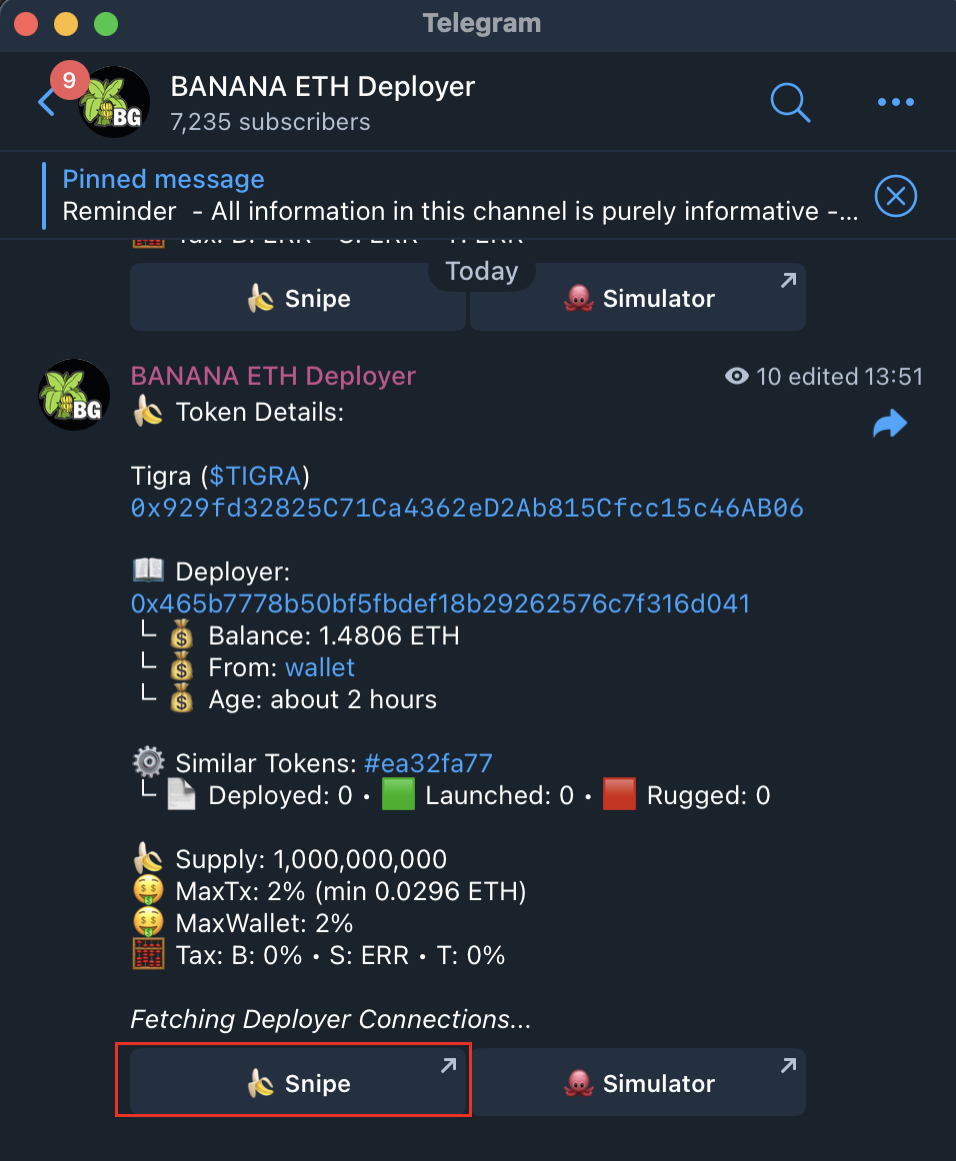

· Telegram Group Advertising

Figure 16 shows a Telegram group maintained by the on-chain sniper bot team Banana Gun, specifically for promoting newly launched tokens. This group not only pushes basic information about new tokens but also provides users with convenient purchasing entry points. When users configure the basic settings of the Banana Gun Sniper Bot, they can quickly purchase the token by clicking the "Snipe" button corresponding to the token promotion information in the group (as highlighted in the red box in Figure 16).

We conducted a manual sampling of the tokens promoted within this group and found that a significant proportion of these tokens were indeed Rug Pull tokens. This finding further deepens our suspicion that Telegram groups are likely an important advertising channel for Rug Pull groups.

The current question is, what proportion of the new tokens pushed by third-party organizations are Rug Pull tokens? What is the scale of operations for these Rug Pull groups? To clarify these issues, we decided to conduct a systematic scan and analysis of the new token data pushed in Telegram groups to reveal the scale of risks and the impact of fraudulent activities behind them.

Ethereum Token Ecosystem Analysis

· Analyzing Tokens Pushed in Telegram Groups

To study the proportion of Rug Pull tokens among the new tokens pushed in these Telegram groups, we crawled the Ethereum new token information pushed by Banana Gun, Unibot, and other third-party token message groups from October 2023 to August 2024 using Telegram's API. We found that during this period, these groups pushed a total of 93,930 tokens.

Based on our analysis of Rug Pull cases, Rug Pull groups typically create liquidity pools for Rug Pull tokens in Uniswap V2 and inject a certain amount of ETH. Once users or new token bots purchase Rug Pull tokens from this pool, attackers profit by dumping the price or removing liquidity. The entire process usually concludes within 24 hours.

Therefore, we summarized the following detection rules for Rug Pull tokens and used these rules to scan the 93,930 tokens, aiming to determine the proportion of Rug Pull tokens among the new tokens pushed in these Telegram groups:

No transfer activity for the target token in the last 24 hours: Rug Pull tokens typically have no further activity after the dump is completed;

Existence of a liquidity pool for the target token and ETH in Uniswap V2: Rug Pull groups create liquidity pools for tokens and ETH in Uniswap V2;

The total number of Transfer events for the token from its creation to the time of detection does not exceed 1,000: Rug Pull tokens generally have low trading volumes, resulting in relatively few transfer counts;

Among the last five transactions involving the token, there are large liquidity pool withdrawals or dumping activities: Rug Pull tokens will execute large liquidity withdrawals or dumping operations at the end of the scam.

Using these rules, we detected the tokens pushed in the Telegram groups, and the results are shown in Table 10.

As shown in Table 9, among the 93,930 tokens pushed in the Telegram groups, a total of 46,526 were detected as Rug Pull tokens, accounting for as high as 49.53%. This means that nearly half of the tokens pushed in the Telegram groups are Rug Pull tokens.

Considering that some project teams may also withdraw liquidity after project failure, such behavior should not be simply classified as the Rug Pull fraud mentioned in this article. Therefore, we need to consider the potential impact of such situations on the analysis results. Although our detection rule number 3 can filter out the vast majority of similar cases, there may still be false positives.

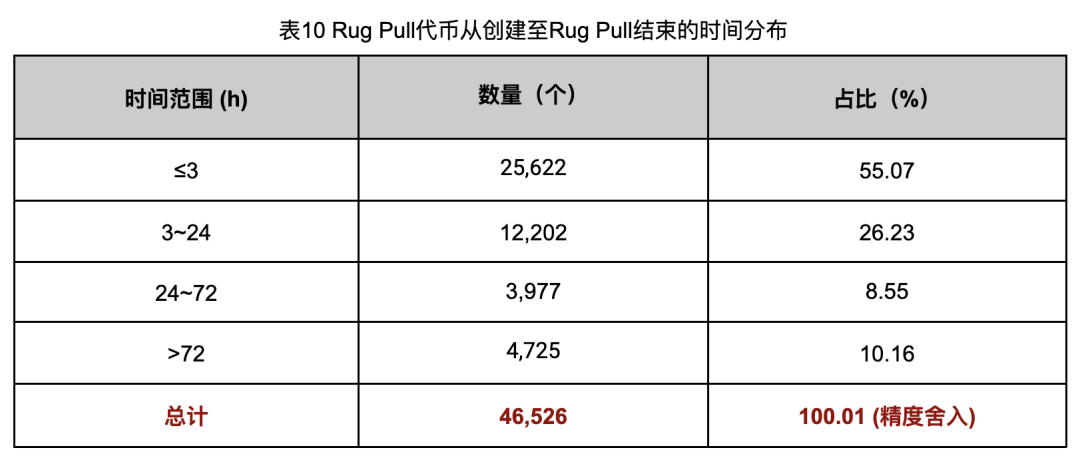

To better understand the impact of these potential false positives, we statistically analyzed the active time of the 46,526 tokens detected as Rug Pull tokens, with the results shown in Table 10. By analyzing the active time of these tokens, we can further distinguish genuine Rug Pull behavior from liquidity withdrawal due to project failure, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the actual scale of Rug Pulls.

Through the statistical analysis of active time, we found that 41,801 Rug Pull tokens had an active time (from token creation to the last execution of the Rug Pull) of less than 72 hours, accounting for as high as 89.84%. Under normal circumstances, a time frame of 72 hours is insufficient to determine whether a project has failed, so this article considers Rug Pull behavior with an active time of less than 72 hours as not a normal project team's withdrawal of funds.

Therefore, even in the least ideal scenario, the remaining 4,725 Rug Pull tokens with an active time greater than 72 hours do not belong to the Rug Pull fraud cases defined in this article. Our analysis still holds high reference value, as 89.84% of the cases meet expectations. In fact, the 72-hour time setting is still relatively conservative, as in actual sampling detection, a considerable portion of tokens with an active time greater than 72 hours still fall within the scope of Rug Pull fraud mentioned in this article.

It is worth mentioning that the number of tokens with an active time of less than 3 hours is 25,622, accounting for as high as 55.07%. This indicates that Rug Pull groups are cycling through their operations with very high efficiency, and their operational style tends to be "short and quick," with extremely high capital turnover rates.

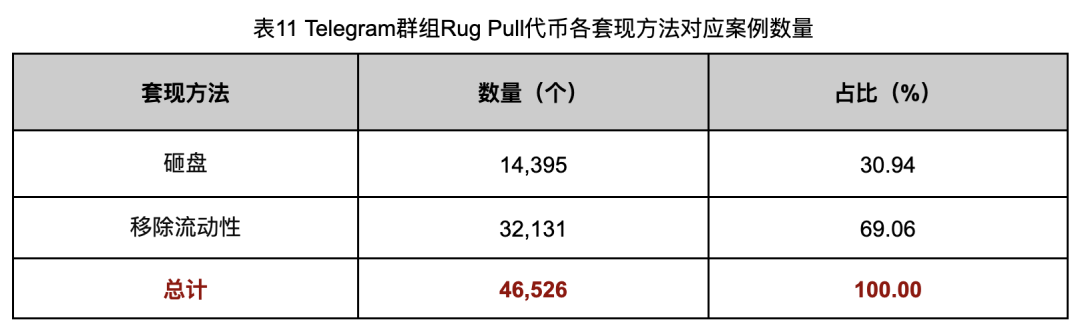

We also evaluated the cash-out methods and contract calling methods of these 46,526 Rug Pull token cases to confirm the operational tendencies of these Rug Pull groups.

The evaluation of cash-out methods mainly involved counting the number of cases corresponding to various methods used by Rug Pull groups to obtain ETH from liquidity pools. The main methods include:

Dumping: Rug Pull groups use tokens obtained through pre-allocation or code backdoors to exchange all ETH in the liquidity pool.

Removing liquidity: Rug Pull groups withdraw all the funds they originally added to the liquidity pool.

The evaluation of contract calling methods involved examining the target contract objects called by Rug Pull groups when executing the Rug Pull. The main objects include:

Decentralized exchange Router contracts: Used for direct manipulation of liquidity.

Custom attack contracts created by Rug Pull groups: Custom contracts used to execute complex fraudulent operations.

By evaluating cash-out methods and contract calling methods, we can further understand the operational patterns and characteristics of Rug Pull groups, thereby better preventing and identifying similar fraudulent behaviors.

The relevant evaluation data for cash-out methods is shown in Table 11.

From the evaluation data, it can be seen that the number of cases where Rug Pull groups cashed out by removing liquidity is 32,131, accounting for as high as 69.06%. This indicates that these Rug Pull groups prefer to cash out by removing liquidity, possibly because this method is simpler and more direct, requiring no complex contract writing or additional operations. In contrast, cashing out through dumping requires Rug Pull groups to pre-set backdoors in the token's contract code, allowing them to obtain the tokens needed for dumping at zero cost. This operational process is more cumbersome and may increase risks, so the number of cases choosing this method is relatively small.

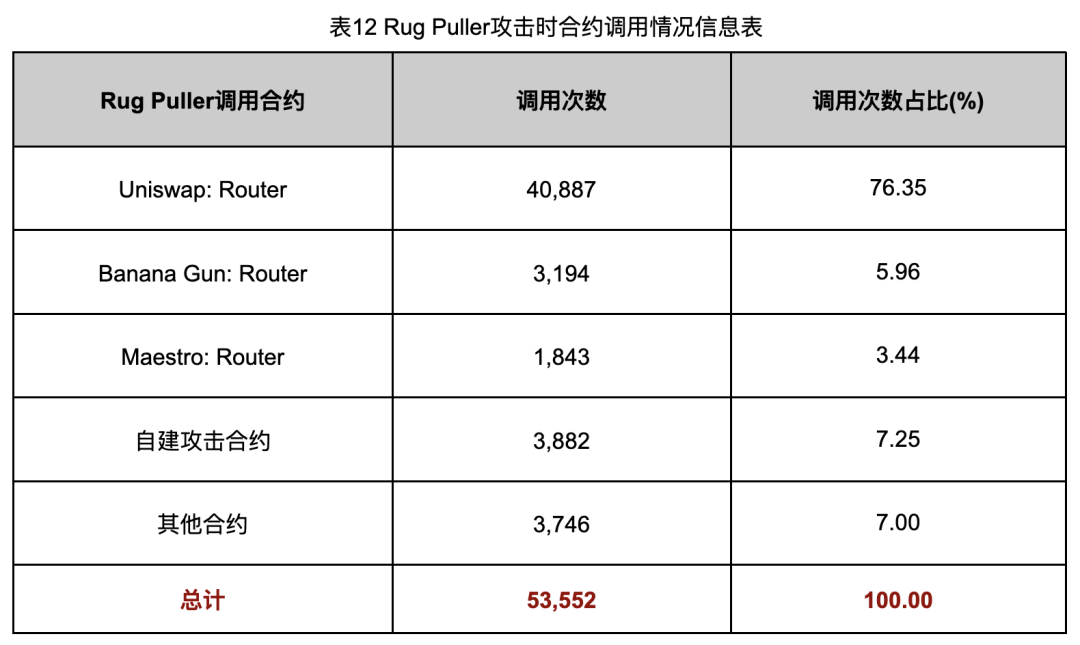

The relevant evaluation data for contract calling methods is shown in Table 12.

From the data in Table 12, it is clear that Rug Pull groups prefer to execute Rug Pull operations through Uniswap's Router contracts, with a total of 40,887 executions, accounting for 76.35% of the total execution count. The total number of Rug Pull executions is 53,552, which is higher than the number of Rug Pull tokens (46,526), indicating that in some cases, Rug Pull groups may execute multiple Rug Pull operations, possibly to maximize profits or to cash out in batches targeting different victims.

Next, we conducted a statistical analysis of the cost and revenue data for the 46,526 Rug Pull cases. It should be noted that we consider the ETH obtained by Rug Pull groups from centralized exchanges or swap services before deploying tokens as costs, while the ETH recovered during the final Rug Pull is considered revenue for related statistics. Since we did not account for the ETH invested by some Rug Pull groups when faking liquidity pool trading volumes, the actual cost data may be higher.

The cost and revenue data is shown in Table 13.

In the statistics of the 46,526 Rug Pull tokens, the total profit amounted to 282,699.96 ETH, with a profit margin of 188.70%, equivalent to approximately $800 million. Although the actual profit may be slightly lower than the above data, the overall scale of funds remains astonishing, demonstrating that these Rug Pull groups have obtained substantial gains through scams.

From the analysis of the entire token data in the Telegram groups, it is evident that the current Ethereum ecosystem is already flooded with a large number of Rug Pull tokens. However, we still need to confirm an important question: do the tokens pushed in these Telegram groups cover all the tokens launched on the Ethereum mainnet? If not, what proportion do they occupy among the tokens launched on the Ethereum mainnet?

Answering this question will provide us with a comprehensive understanding of the current token ecosystem on Ethereum. Therefore, we began to conduct an in-depth analysis of the tokens on the Ethereum mainnet to determine the coverage of tokens pushed in Telegram groups within the entire mainnet tokens. Through this analysis, we can further clarify the severity of the Rug Pull issue within the entire Ethereum ecosystem and the influence of these Telegram groups in token promotion and marketing.

· Analyzing Tokens Issued on the Ethereum Mainnet

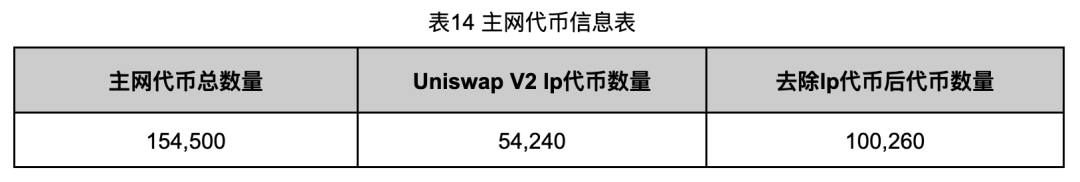

We crawled the block data corresponding to the same time period (from October 2023 to August 2024) as the analysis of the Telegram group token information through RPC nodes, obtaining newly deployed tokens from these blocks (excluding tokens that implement business logic through proxies, as there are very few Rug Pull cases involving tokens deployed via proxies). The final number of captured tokens was 154,500, of which the number of Uniswap V2 liquidity pool (LP) tokens was 54,240, and LP tokens are not within the scope of this observation.

Therefore, we filtered out the LP tokens, resulting in a final count of 100,260 tokens. Relevant information is shown in Table 14.

We conducted Rug Pull rule detection on these 100,260 tokens, and the results are shown in Table 15.

Among the 100,260 tokens subjected to Rug Pull detection, we found that 48,265 tokens were Rug Pull tokens, accounting for 48.14% of the total, a proportion roughly equivalent to that of Rug Pull tokens in the tokens pushed in Telegram groups.

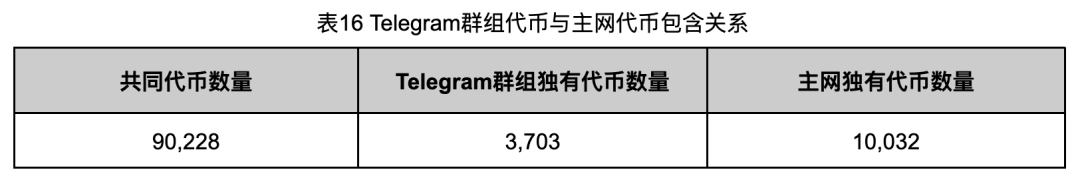

To further analyze the inclusion relationship between the tokens pushed in Telegram groups and all tokens launched on the Ethereum mainnet, we conducted a detailed comparison of the information from these two groups of tokens, with the results shown in Table 16.

From the data in Table 16, it can be seen that there are 90,228 tokens in the intersection between the tokens pushed in Telegram groups and the tokens captured on the mainnet, accounting for 89.99% of the mainnet tokens. There are 3,703 tokens in the Telegram groups that are not included in the tokens captured on the mainnet. Through sampling detection, we found that these tokens are all tokens that implement contract proxies, which we did not include when capturing mainnet tokens.

As for the tokens on the mainnet that were not pushed by Telegram groups, there are 10,032 tokens. The reason for this may be that these tokens were filtered out by the push rules of the Telegram groups, possibly due to a lack of sufficient appeal or not meeting certain push standards.

To further analyze, we conducted Rug Pull detection specifically on these 3,703 tokens that implemented contract proxies, and ultimately found only 10 Rug Pull tokens. Therefore, these contract proxy tokens do not significantly interfere with the Rug Pull detection results of the tokens in the Telegram groups, indicating a high consistency between the Rug Pull detection results of the tokens pushed in Telegram groups and those of the mainnet tokens.

The addresses of these 10 Rug Pull tokens that implemented proxies are listed in Table 17. If interested, readers can check the relevant details of these addresses themselves, and this article will not elaborate further.

Through this analysis, we confirm that the tokens pushed in Telegram groups have a high overlap in the proportion of Rug Pull tokens with the mainnet tokens, further validating the importance and influence of these push channels in the current Rug Pull ecosystem.

Now we can answer the question of whether the tokens pushed in Telegram groups cover all the tokens launched on the Ethereum mainnet, and if not, what proportion they occupy.

The answer is that the tokens pushed in Telegram groups account for about 90% of the mainnet, and their Rug Pull detection results are highly consistent with the Rug Pull detection results of the mainnet tokens. Therefore, the previous Rug Pull detection and data analysis of the tokens pushed in Telegram groups can essentially reflect the current state of the token ecosystem on the Ethereum mainnet.

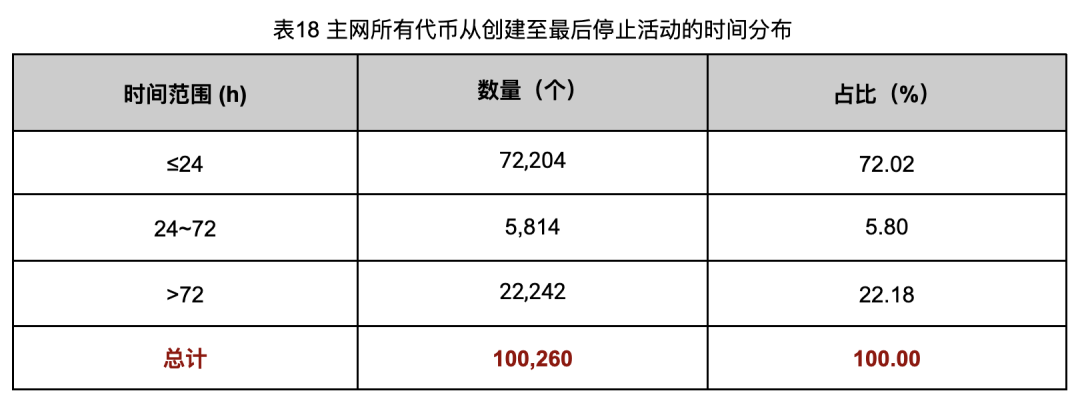

As mentioned earlier, the proportion of Rug Pull tokens on the Ethereum mainnet is approximately 48.14%, but we are also interested in the remaining 51.86% of non-Rug Pull tokens. Even excluding Rug Pull tokens, there are still 51,995 tokens in an unknown state, a number that far exceeds our expectations for a reasonable number of tokens. Therefore, we conducted a statistical analysis of all tokens on the mainnet from creation to the last activity cessation, with the results shown in Table 18.

From the data in Table 18, we can see that when we expand our view to the entire Ethereum mainnet, the number of tokens with a lifecycle of less than 72 hours is 78,018, accounting for 77.82% of the total. This number is significantly higher than the number of Rug Pull tokens we detected, indicating that the Rug Pull detection rules mentioned in this article do not fully cover all Rug Pull cases. In fact, through sampling detection, we did find undetected Rug Pull tokens. At the same time, this may also imply that there are other forms of fraud not covered, such as phishing attacks, Ponzi schemes, etc., which still require further exploration.

Additionally, the number of tokens with a lifecycle greater than 72 hours is also as high as 22,242. However, this portion of tokens is not the focus of this article, so there may still be other details waiting to be discovered. Perhaps some of these tokens represent failed projects or projects with a certain user base that failed to receive long-term support, and the stories and reasons behind these tokens may hide more complex market dynamics.

The token ecosystem on the Ethereum mainnet is much more complex than we initially imagined, with various short-term and long-term projects intertwined, and potential fraudulent activities emerging continuously. This article aims to raise awareness, hoping that everyone can realize that in our unknown corners, criminals have been quietly operating. We hope that through this analysis, we can inspire more people to pay attention and research, thereby improving the security of the entire blockchain ecosystem.

Reflection

The proportion of Rug Pull tokens among the newly issued tokens on the current Ethereum mainnet is as high as 48.14%, a ratio that serves as a significant warning. It means that on Ethereum, on average, for every two tokens launched, one is used for fraud, reflecting a certain degree of chaos and disorder in the current Ethereum ecosystem. However, what is truly concerning goes far beyond the current state of the Ethereum token ecosystem. We found that in the Rug Pull cases captured by on-chain monitoring programs, the number of cases from other blockchain networks is even greater than that of Ethereum. What is the state of the token ecosystem on these other networks? This is also worth further in-depth research.

Moreover, even excluding the 48.14% of Rug Pull tokens, Ethereum still sees about 140 new tokens launched daily, and its daily issuance range remains far above a reasonable level. Are there other undisclosed secrets hidden among these unaddressed tokens? These questions are worth our deep reflection and study.

At the same time, there are many key points in this article that require further exploration:

- How to quickly and efficiently determine the number of Rug Pull groups in the Ethereum ecosystem and their connections?

Given the large number of Rug Pull cases detected, how can we effectively determine how many independent Rug Pull groups are hidden behind these cases and whether there are connections between these groups? This analysis may need to combine the flow of funds and address sharing situations.

- How to more accurately distinguish between victim addresses and attacker addresses in Rug Pull cases?

Distinguishing between victims and attackers is an important step in identifying fraudulent behavior, but the boundary between victim addresses and attacker addresses is often blurred. How to make this distinction more precise is a question worth in-depth research.

- How to move Rug Pull detection to during or even before the event?

Current Rug Pull detection methods are mainly based on post-analysis. Is it possible to develop a method for detecting during or before the event to identify potential Rug Pull risks in currently active tokens in advance? This capability would help reduce investor losses and allow for timely intervention.

- What are the profit strategies of Rug Pull groups?

Researching under what profit conditions Rug Pull groups will execute a Rug Pull (for example, at what average profit they choose to run away, as referenced in Table 13 of this article), and whether they use certain mechanisms or means to ensure their profits. This information can help predict the occurrence of Rug Pull behavior and strengthen prevention.

- Are there other promotional channels besides Twitter and Telegram?

The Rug Pull groups mentioned in this article mainly promote their fraudulent tokens through channels like Twitter and Telegram, but are there other potential promotional channels that could be exploited? For example, forums, social media, advertising platforms, etc. Do these channels also carry similar risks?

These questions are all worth our in-depth exploration and consideration, and we will not elaborate further here, leaving them for everyone's research and discussion. The Web3 ecosystem is rapidly evolving, and ensuring its security relies not only on technological advancements but also on more comprehensive monitoring and deeper research to address the ever-changing risks and challenges.

Recommendations

As mentioned earlier, the current token launch ecosystem is filled with numerous scams. As Web3 investors, a slight misstep can lead to losses. With the escalating cat-and-mouse game between Rug Pull groups and anti-fraud teams, the difficulty for investors to identify fraudulent tokens or projects is continuously increasing.

Therefore, for investors looking to enter the token launch market, our security expert team offers the following suggestions for reference:

Purchase new tokens through well-known centralized exchanges whenever possible: Prioritize purchasing new tokens from reputable centralized exchanges, as these platforms have stricter project review processes and relatively higher security.

When buying new tokens through decentralized exchanges, verify their official website and on-chain address: Ensure that the tokens you purchase come from the contract addresses officially released by the project to avoid accidentally buying fraudulent tokens.

Before purchasing new tokens, verify whether the project has an official website and community: Projects without an official website or active community often carry higher risks. Pay special attention to new tokens pushed by third-party Twitter and Telegram groups, as these promotions are mostly not security-verified.

Check the creation time of the token and avoid purchasing tokens created less than 3 days ago: If you have a certain technical background, you can check the token's creation time through a block explorer. Try to avoid purchasing tokens that were created less than 3 days ago, as the active time of Rug Pull tokens is usually very short.

Use token scanning services from third-party security agencies: If conditions permit, utilize token scanning services provided by third-party security agencies to assess the safety of the target token.

Call to Action

In addition to the Rug Pull scam groups focused on in this article, an increasing number of similar criminals are exploiting the infrastructure and mechanisms of various fields or platforms within the Web3 industry for illegal profit, making the current security situation of the Web3 ecosystem increasingly severe. We need to start paying attention to some issues that are easily overlooked in daily life, preventing criminals from finding opportunities.

As mentioned earlier, the inflow and outflow of funds from Rug Pull groups ultimately flow through major exchanges. However, we believe that the funds involved in Rug Pull scams are just the tip of the iceberg, and the scale of malicious funds flowing through exchanges may far exceed our imagination. Therefore, we strongly urge major exchanges to implement stricter regulatory measures against these malicious fund flows and actively combat illegal fraudulent activities to ensure the safety of user funds.

Similar to project promotion and on-chain sniper bots, third-party service providers' infrastructure has, in fact, become a tool for scam groups to profit. Therefore, we call on all third-party service providers to strengthen the security review of their products or content to avoid being maliciously exploited by criminals.

At the same time, we urge all victims, including MEV arbitrageurs and ordinary users, to actively use security scanning tools to assess target projects before investing in unknown projects, refer to authoritative security agencies' project ratings, and proactively disclose the malicious behaviors of criminals to expose illegal activities in the industry.

As a professional security team, we also call on all security practitioners to actively discover, identify, and combat illegal activities, and to be diligent in voicing concerns to safeguard users' financial security.

In the Web3 field, users, project parties, exchanges, MEV arbitrageurs, and third-party service providers such as bots all play crucial roles. We hope that every participant can contribute to the sustainable development of the Web3 ecosystem, working together to create a safer and more transparent blockchain environment.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。