On the surface, technology drives the transfer of economic power, but in fact, the technology before blockchain relied on the promotion of power. Although digital currency reshapes the economic power structure through decentralization, it is essentially a transfer technology and has not solved the three dilemmas of traditional finance.

Author: VC Popcorn

Abstract

- This article is an academic survey aimed at exploring the operation logic, value, and impact of digital currency and its subjects in economic activities.

- Transfer of economic power: Investment or speculation in digital currency actually reflects people's pursuit and desire for economic power.

- Impact of currency technology on economic power: On the surface, the iteration of currency technology has led to the transfer of currency power, but before the emergence of blockchain, this process was more driven by political power and military force.

- Core issues of digital currency: P2P transfer technology has reshaped the existing economic power structure with its decentralization feature, but it has not solved the three dilemmas of traditional finance. Its essence is still transfer technology, not a true currency.

- Conclusion: Some "investment institutions" advocate that Bitcoin is the future currency, showing a lack of economic common sense, as Bitcoin is not suitable as a unit for daily transactions.

01. Introduction

This article is an academic discussion, and we have conducted a lot of academic research and references; it does not involve any investment advice or related content. The article mainly analyzes the technical characteristics of digital currency represented by Bitcoin, delves into its role, influence, and value in the macro economy, and further dissects the underlying operating logic of the Web3 world, providing theoretical support for it.

02. Evolution of Currency and Transfer of Economic Power

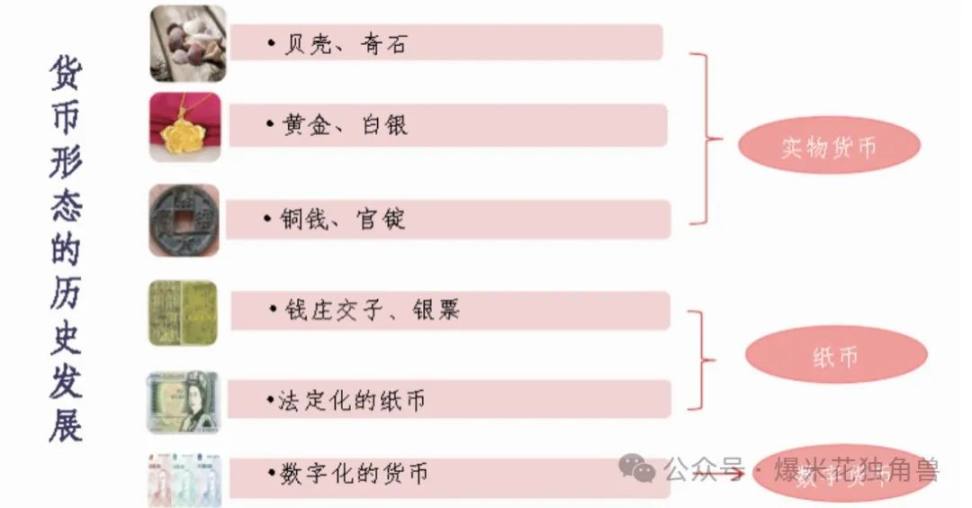

2.1 Evolution of Currency and Trust Carrying

As a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account, currency carries the trust and commitments between various parties within and outside society. However, the demand for the role of currency in economic activities is constant, while the form of currency evolves with the development of technology and society. From the earliest shells and metals to today's paper money, the forms vary, but they all continuously evolve to meet human needs. Currency is not only a medium of economic activity but also a reliable technology that enables commitments between economic entities. As economic activities become more complex, currency technology also continues to develop.

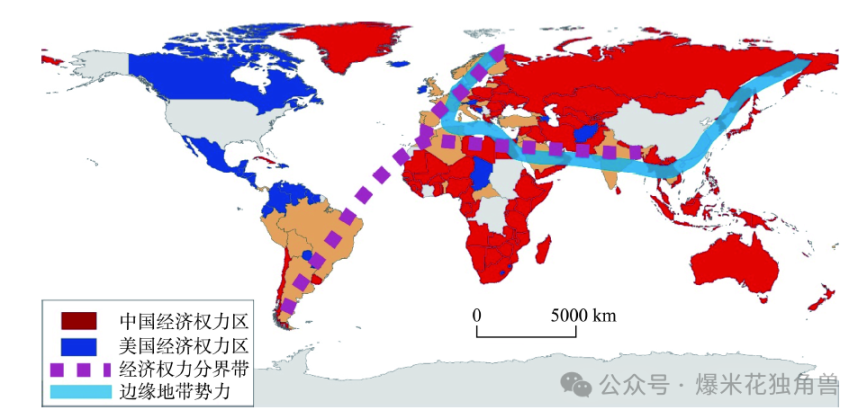

2.2 Transfer of Economic Power

What is economic power? In the words of economist Richard Cooper, economic power is the ability to apply economic means to punish or reward another party (Eichengreen, 2022). This ability is usually the result of its economic scale, and it is the foundation of economic growth. Economic strength is related to a country's purchasing power. Purchasing power is determined by the strength of the national currency. For example, the US dollar is currently considered the most powerful currency, to the extent that other countries use it as an emergency reserve currency for their central banks. In 1920 and 2008, we witnessed global economic crises caused by the collapse of the value of the US dollar.

Digital currency represents the latest stage of currency technology. Digital currencies led by Bitcoin seem to provide an opportunity for ordinary investors to grasp economic power, with the view that Bitcoin is another form of central bank. They believe that digital currency technology is not only to solve economic efficiency issues but more importantly, it impacts and reshapes the power relations in the existing economic field.

This is also why various industries and early governments initially regarded digital currency as a monster, but now they are forced to accept it and need to actively embrace it, because the top-level design of digital currency directly affects the trend of influence in economic competition for all parties. Therefore, we want to delve into the dynamic relationship between the development of digital currency and economic power.

03. Impact of Currency Technology on Economic Power

3.1 Currency Technology and Transaction Efficiency

History has told us that the emergence of currency greatly improved transaction efficiency, and the progress of currency technology mainly serves transaction efficiency (Jenkins, 2014). Under the premise of "trust," trading parties usually choose the most efficient currency as the trading medium, so the innovation and application of currency technology profoundly affect the economic structure, thereby changing the distribution of economic power. In other words, the leader of economic activities is usually the master of the most advanced currency technology.

As we know, the earliest appearance of currency was to solve the "double coincidence" requirement in ancient trade, which was the main problem faced in trade through barter (i.e., exchanging goods for goods) in a non-monetary economy (O'Sullivan & Sheffrin, 2003).

This trading method was inefficient and limited the scale and scope of transactions. The introduction of precious metal currency greatly simplified this process (Crawford, 1985), making economic activities more fluid and extensive. The currency technology of this period was relatively primitive, and the value of currency depended on the value of the precious metal itself. However, the inconvenience of carrying and trading precious metals, as well as the scarcity and high production cost of metals such as gold and silver, posed challenges.

Therefore, the world economy needed a portable and less producible emerging currency. The invention of paper money and the use of banknotes were significant advances in currency technology, first appearing in the Song Dynasty in China (Moshenskyi, 2008), and later spreading to Europe, greatly improving the circulation efficiency of currency.

With the paper currency system, Britain developed a complex banking system and credit currency system in the 17th century (Richards, 2024), which promoted the Industrial Revolution and expanded its global economic and military influence.

From the late 20th century to the early 21st century, the emergence of electronic currency and payment systems (such as credit cards and electronic transfers) further revolutionized currency technology (Stearns, 2011), improving the efficiency of financial markets and enhancing a country's economic control. For example, the US financial system and the global dominance of the US dollar partly benefited from its central position in the global payment system, such as the SWIFT system (Gladstone, 2012).

3.2 Power Driving Currency Innovation

Undoubtedly, each new currency technology's emergence is an improvement over the previous inefficient currency. However, this does not explain why people are willing to accept a "currency" that has no intrinsic value as a trading medium, as mentioned earlier, under the premise of "trust," who provides or guarantees trust?

In fact, the change in the form of currency is not just a technological iteration in economic activities, but more often, it is a choice of the party that controls power in commercial activities to maximize its own interests, coinciding with the development of technology. Usually, the party with stronger technological capabilities also holds more power in commercial activities. In other words, the party controlling power provides security or represents security, whether through advanced weapon technology or advanced currency technology.

For example, between economic entities.

India used shells as the basic currency from the Neolithic Age until the 18th and 19th centuries when the British began to colonize India. To better control the Indian economy and facilitate tax collection, the East India Company introduced paper money in 1812 (Tanabe, 2020). Initially, these banknotes were optional and not mandatory for public use; by 1861, the Paper Currency Act was passed (Lopez, 2021), establishing "Company Rupees" as the legal currency of India. This meant that all public and private debts had to be settled using Company Rupees, becoming the sole legal means of payment.

The iterative upgrade of currency technology did not receive a warm welcome from the Indian people because it increased the dissatisfaction of the local population. Paper money strengthened the economic exploitation of the Indian people by the British government, making it easier for them to levy taxes and extort money. These grievances eventually led to broader protests and resistance activities (Tanabe, 2020).

In the end, the Indian people were forced to accept advanced paper money, based on a compromise with advanced military technology, rather than recognition of the advancement of currency technology. This is similar to the current world economic situation, where the technological and military attributes of the US dollar are indispensable, and their combination ensures its financial attributes, thereby achieving safe and convenient trade.

(3) Successes and Failures of Technological Advancements in Currency Power Transfer

Secondly, within an economic entity, the party that masters technology often challenges the original dominant power, as seen in successful cases such as credit cards. This is an example of how technological and business model innovation shifted the power of currency supply from the government to private financial institutions.

The original credit card system was introduced by Diners Club in the 1950s, followed by brands like Visa and Mastercard introducing their own credit card products (Stearns, 2011). These cards allowed consumers to make purchases without immediate cash payment, with the promise to repay the debt at a future date.

From a technological perspective, credit cards did not directly change the money supply (i.e., the currency supply indicators controlled by central banks such as M1 and M2), as credit cards actually created a form of "credit currency" or lending, rather than actual money supply (Stearns, 2011). However, credit cards did function similarly to currency in actual economic activities, affecting currency circulation through credit creation. This reflects the decentralization of power and function in the modern financial system (Simkovic, 2009).

In the case of failures, for example, even before the emergence of Bitcoin, in 1983, David Chaum, a cryptographer and pioneer of digital privacy, proposed "blind signature" technology (Chaum, 1983). Blind signatures are a form of digital signature in which the content of the message is hidden from the signer before it is signed (Chaum, 1983). This means that the signer can sign without knowing the message content, but can later verify the authenticity and integrity of the message after signing.

The blind signature system invented by David Chaum was initially intended to serve large financial or government institutions, as it helped increase the transparency of data processing without sacrificing privacy. However, early distributed ledger technologies like this were based on a common assumption: the existence of a central authority, such as traditional retail banks or central banks. Therefore, these proposals failed to avoid centralized power structures (Tschorsch & Scheuermann, 2016).

In conclusion, currency technology can influence economic structure and thus economic power, but the promotion and popularization of currency technology also heavily depend on the support of the dominant party in the existing economic system. Currency technologies before blockchain needed the support of strong government authority to expand.

04. Challenges and Helplessness of Blockchain Technology to Economic Order

4.1 Bitcoin: Resistance to Centralized Economy

The emergence of Bitcoin in 2008 represented a thorough resistance to the phenomenon and order of centralized economy. Its birth stemmed from dissatisfaction with the traditional financial system, specifically the dissatisfaction with the financial system controlled by central governments, and was a social response to the global financial crisis (Nakamoto, 2008). Its core proposal was to establish a decentralized economic system, abandoning intermediary institutions such as central banks (Joshua, 2011). This was not only a response to the financial crisis but also a technological commitment to overcoming barriers to digital currency development (Marple, 2021).

The blockchain technology created alongside Bitcoin initially faced significant skepticism from the tech community. After withstanding numerous hacker attacks, its security was finally recognized by the tech community (Reiff, 2023).

Hackers discovered that blockchain technology could facilitate peer-to-peer transactions across oceans without the need for any intermediaries or permissions, and in the process, the transaction results could not be tampered with (Reiff, 2023). This was the first time a currency technology itself provided enough trust, without relying on centralized power. In other words, this technology achieved trustless and permissionless P2P transactions. As a result, blockchain technology created a new species of currency, digital currency (Nakamoto, 2008).

4.2 Rise of Altcoins and Competition in Technological Innovation

Starting from 2011, a large number of altcoins emerged based on blockchain technology, maintaining decentralized technical characteristics but differing in the application of blockchain technology. These altcoins achieved social and economic goals in different ways (Halaburda & Gandal, 2016).

In the altcoin ecosystem, we can clearly see the relationship between technological innovation and the iteration of transaction efficiency, whether through the iteration of consensus protocols (such as POW, POS, and POS) or through Layer2 to increase the flexibility of the mainnet, all aimed at increasing transaction efficiency (Halaburda & Gandal, 2016). At the same time, we find that while digital currencies decentralize the traditional financial world, internally, they engage in power games, with various altcoins constantly iterating or boasting about their digital currency technology, thereby continuously challenging the throne of power.

As a result, Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) emerged. In 2013, Mastercoin was the world's first ICO, but Ethereum's ICO in 2014 was more widely known (HackerNoon.com, 2019). Companies preparing for ICOs typically release a roadmap, indicating the need to raise funds to develop the most advanced digital currency technology or to expand and strengthen their crypto ecosystem, among other things. ICOs allow companies or organizations to raise funds by offering cryptocurrency tokens instead of stocks. These tokens usually do not provide ownership of the company but allow buyers to profit from the company's success and use the tokens to purchase products or services (Hargreaves, 2013). Often, these ICOs are more centrally managed by the issuing company, meaning that the authority is in the hands of the issuing company rather than being completely decentralized.

Furthermore, ICOs are designed for company value, with buyers expecting the company to continue creating value, iterating technology, and expanding the ecosystem, unlike Bitcoin itself, where expectations of its value come entirely from consensus, and users do not expect Bitcoin to evolve into additional value.

ICOs go beyond the definition of digital currency itself and become an alternative to securities (Hargreaves, 2013). Therefore, in 2021, when Sam Bankman-Fried proposed a completely different way of managing and regulating digital currencies to the US SEC, it was immediately rejected (SEC document, 2022) because at the time, no one could clearly explain the difference between the two from this perspective.

4.3 The Rise of Stablecoins and the Contest for Economic Power

We have witnessed the birth of stablecoins, with USDT appearing in 2014 (Cuthbertson, 2018). By maintaining a stable price relationship with the US dollar, stablecoins reduce price volatility in the cryptocurrency market. Through this method, stablecoins such as USDT attempt to become the central figure in cryptocurrency transactions. Thanks to the stability brought by stablecoins, both decentralized finance and centralized cryptocurrency trading have flourished. Here, the relationship between efficiency gains and economic power is clearly visible.

Many people believe that stablecoins, such as USDT, anchor the influence of digital currencies to traditional currencies, representing a technological regression. This has led to the emergence of algorithmic stablecoins, but I won't delve into that here. From another perspective, central banks around the world see stablecoins as an opportunity for new power expansion, allowing them to claim the throne of the crypto world through stablecoins.

Central banks worldwide are conducting pilot projects for sovereign digital currencies, with the most well-known being Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC). A recent survey by the Bank for International Settlements shows that over 70% of central banks are actively researching their own CBDC. China's digital yuan is one of the most well-known CBDC projects (Barontini & Holden, 2019).

It is worth noting that many countries are already using digital currencies to circumvent international sanctions, while also pursuing central bank digital currency projects to more effectively achieve this goal (Barontini & Holden, 2019). Typically, powerful governments use non-violent force through their sovereign currencies, especially in international relations. By controlling currency, governments can influence the economic activities of other countries and individuals (Barontini & Holden, 2019). Particularly in international sanctions, if Country A wants to impose economic sanctions on Country B, it can do so by cutting off Country B's access to the SWIFT system, preventing Country B's financial institutions from accessing international financial markets.

However, digital currencies challenge this inherent rule. If Country B develops its own central bank digital currency (CBDC) and establishes a direct encrypted trading channel with other countries, it can bypass the restrictions of the SWIFT system and reduce the impact of sanctions. This demonstrates that CBDCs help reduce the control of certain countries in international financial flows, thereby disrupting the traditional rules of economic sanctions. This once again confirms the significant weakening of power structures within existing economic systems by digital currencies.

In summary, whether in fully decentralized digital currencies, enterprise ICOs, or government-produced stablecoins, we see the important connection between the advancement of currency technology and the pursuit of economic power.

5. Reflections on the Operating Rules of Digital Currencies

I believe that everyone who comes into contact with digital currencies will ponder this question: what is the use of digital currencies, and how are they used? Or, what are the operating rules of digital currencies, and can I strike it rich by mastering these rules?

Today, I still cannot help anyone strike it rich, but I can discuss the underlying logic of the operation of digital currencies. There are three questions that I consider to be the most important, and these three questions are also the most concerning for traditional financial institutions: 1. What is the value of digital currencies? 2. What mechanisms control and influence the price of digital currencies? 3. What is the impact of digital currency ledger technology on traditional financial behavior?

5.1 What is the Value of Digital Currencies?

I believe there are generally four types of value:

Transaction value itself (Nakamoto, 2008), as a means of transaction. Its rapid, decentralized nature allows for transactions that traditional finance cannot achieve through digital currencies.

Speculative value (Gronwald, 2019), such as Bitcoin. Its limited supply makes it more like a commodity than a currency.

Anchored value (Dell’Erba, 2019), such as stablecoins, which are tied to the value of an actual asset.

Function-based value (Golem, 2020), such as privacy coins, which allow users to keep transaction information on the blockchain confidential. Various coins can also be used to access services on a specific blockchain network, such as using ionet coins to purchase GPU services.

The first type of value is the target of active control and crackdown by sovereign nations.

The second type of value has given rise to a large speculative market, which is not tolerated by financial regulatory authorities, leading to numerous warnings.

The third type of value has found a natural place in the banking industry and therefore falls under the scope of banking regulatory authorities.

The fourth type of value has spread in terms of corporate fundraising and is subject to securities regulation.

5.2 What Mechanisms Control and Influence the Price of Digital Currencies?

The price of digital currencies is closely related to their supply management mechanism, similar to traditional fiat currencies.

For sovereign fiat currencies, price control is achieved through supply management. Sovereign governments influence confidence and liquidity of the currency in economic activities by issuing or destroying currency (Fenu, Marchesi, Marchesi & Tonelli, 2018). This leads to a traditional currency policy dilemma, also known as the "impossible trinity" in economics, referring to the three main goals a country faces when formulating its monetary policy (Lawrence & Frieden, 2001): exchange rate stability, free capital movement, and independent monetary policy. These three goals are usually difficult to achieve simultaneously, and a country must choose two out of the three.

If a country chooses a fixed exchange rate and allows free capital movement, it will be difficult to maintain an independent monetary policy. This is because a fixed exchange rate requires the country's monetary policy to be consistent with major trading partners or currency anchors to maintain the exchange rate target. At the same time, free capital movement allows market forces (such as speculation) to exert pressure on the fixed exchange rate, which may force the country to adjust its monetary policy to maintain exchange rate stability (Lawrence & Frieden, 2001).

If a country chooses an independent monetary policy and allows free capital movement, it will be difficult to maintain exchange rate stability. In this case, the central bank adjusts interest rates or money supply to achieve domestic goals, such as combating inflation or stimulating the economy, which may lead to capital inflows or outflows, affecting the exchange rate (Lawrence & Frieden, 2001).

If a country chooses an independent monetary policy and maintains exchange rate stability, it may need to restrict the free movement of capital. This is because the free movement of capital may exert pressure on the exchange rate, conflicting with the country's independent monetary policy (Lawrence & Frieden, 2001).

A prime example of this is that China has chosen a relatively independent monetary policy and stable exchange rate, while Eurozone countries have chosen exchange rate stability and free capital movement (Lawrence & Frieden, 2001).

Some cryptocurrencies have also demonstrated this central issuance supply logic (Jani, 2018), such as Ripple (XRP). A large amount of Ripple was created through a pre-mining model before public issuance, and the management company of Ripple can increase or decrease the circulating supply of Ripple as needed to maintain the cost and efficiency of cross-border transfers, thereby controlling the price (Jani, 2018). Although this supply control strategy can help stabilize prices, it also introduces centralized risks, similar to the issuance and adjustment logic of traditional fiat currencies. Ripple will inevitably face the "impossible trinity" in economics, especially since the risk resistance of individual companies is much lower than that of sovereign nations. Once a debt crisis occurs, hyperinflation may occur.

Another method is algorithmic supply (Yermack, 2015). Unlike central issuance, algorithmic supply relies on preset rules to automatically control the generation and issuance of digital currencies. These rules are embedded in the blockchain code and do not require human intervention (Yermack, 2015). Bitcoin is a typical example, with its supply limit fixed at 21 million and expected to reach this limit around 2140 (Nakamoto, 2008). This preset supply rate makes Bitcoin's supply predictable, but it also makes it more sensitive to market speculation, leading to greater price volatility. Despite the high price volatility, the characteristics of algorithmic supply, such as supply predictability, make these currencies very useful in trading. Traders can predict their performance relative to other currencies based on the known supply patterns, enabling strategic buying and selling.

In summary, in the field of digital currencies, the central issuance mechanism allows for more flexible management of prices and supply, but may raise credibility issues as market participants may be concerned about the abuse of central power, such as the occurrence of hyperinflation. In contrast, algorithmic supply (such as Bitcoin's fixed limit) provides a high level of predictability and transparency, increasing the credibility of the currency but sacrificing the ability to respond quickly to market changes.

5.3 What is the Impact of Digital Currency Ledger Technology on Traditional Financial Behavior?

The design of blockchain distributed ledger technology represents a significant innovation in traditional ledger technology (Nakamoto, 2008). Whether a digital currency ledger is public or private also has a significant impact on its role in economic relationships and the acceptance level by regulatory authorities.

In a public ledger, the responsibility for record-keeping is distributed among a large number of end users, forming a decentralized governance structure. Anyone can view and verify transactions in the ledger, so public ledgers are generally considered more transparent and decentralized (Nakamoto, 2008). In contrast, private ledgers have a more centralized responsibility structure, usually carried by an organization. This means that the cost of ledger management is concentrated in an organization or group of actors, rather than being distributed across the entire network.

Because public ledgers lack a centralized regulatory entity, regulatory authorities need to supervise more participants, and may therefore take more aggressive prohibitions and warnings to manage the cryptocurrency market (O’Dwyer & Malone, 2014). Private ledgers, managed by specific organizations, allow regulatory authorities to more easily implement specific governance responses, as they can communicate and collaborate directly with these organizations. For example, traditional bank ledgers are usually centralized, meaning that all data and transaction records are stored on the bank's internal servers. Government departments only need to constrain and manage the banks.

Bitcoin chose a public ledger because it is a decentralized digital currency, emphasizing the decentralization of finance and currency (Nakamoto, 2008). This bypasses the traditional banking model, where cross-border remittances and large transactions typically involve complex intermediaries and high fees, and also bypasses effective government regulation. This has led to regulatory authorities taking more stringent measures to manage its market. This indicates that the development and adoption of digital currencies is not just a technological choice, but also involves power struggles and decisions across multiple levels such as politics, economics, and society.

06. Conclusion

Digital currency is the latest stage in the development of currency. The term "digital currency" represents its technological and monetary attributes, with "crypto" representing its encryption technology and "currency" representing its monetary attributes.

Its technological attributes have been perfectly demonstrated as a payment tool, solving many problems that traditional banks cannot solve. Through its global distributed ledger system, it enables fast, direct cross-border transfers, greatly reducing transaction costs and time, without the need for intermediaries and approvals. However, most currency technologies need the support of centralized economic powers to develop. Blockchain technology has achieved vigorous development without the need for vested interests, launching a direct attack on the traditional economic order. Within the realm of digital currencies, countless altcoins are also attacking the inherent economic structure of digital currencies (such as Bitcoin and Ethereum) through continuous technological iterations. Therefore, the endless stream of ICO coins, although not generating cash flow in the short term, seems to indicate that investors see their future significant value in transaction efficiency.

However, if digital currency is viewed as a currency itself, the economic and political issues it faces are not much different from traditional fiat currencies. Problems encountered in traditional economic activities, such as the impossible trinity, have not been resolved in the field of digital currencies. Based on this, we have also found that in this touted decentralized crypto world, there is a strong emphasis and worship of orthodoxy, which is centralized, centripetal, and even superstitious, contrary to its technological attributes. This phenomenon is very similar to the obsession and worship of power in the traditional world, disregarding scientific principles.

This is why some crypto institutional investors absurdly and self-righteously proclaim that Bitcoin is equivalent to a central bank, and the operating model of other digital currencies is comparable to that of a country, demonstrating ignorance of economic knowledge.

Reference

Jenkins, 2014. The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

O'Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 243. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

Moshenskyi, Sergii (2008). History of the Weksel: Bill of Exchange and Promissory Note. Xlibris. pp. 50.

Crawford, Michael H. (1985). Coinage and Money under the Roman Republic, Methuen & Co. ISBN 0-416-12300-7

Kelly Richards (2024) The Evolution of Banking in the UK, source

Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023. Available through SpringerLink.

Gladstone, Rick (3 February 2012). "Senate Panel Approves Potentially Toughest Penalty Yet Against Iran's Wallet". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

Rachel Lopez "Cash of the titans: How India's paper money came to be". Hindustan Times. 26 March 2021.

Tanabe, Akio. 2020. “Genealogies of the ‘Paika Rebellion’: Heterogeneities and Linkages.” International Journal of Asian Studies17 (1): 1–18.

Trump, Benjamin D., EmilyWells, Joshua Trump, and Igor Linkov. 2018. “Digital Currency: Governance for What Was Meant to Be Ungovernable.” Environment Systems and Decisions 38 (3): 426–30.

Stearns, David L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84996-138-7. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023. Available through SpringerLink.

Simkovic, Michael. 2009. “The Effect of BAPCPA on Credit Card Industry Profits and Prices.” American Bankruptcy Law Review 83: 1.

Chaum, David (1983). "Blind Signatures for Untraceable Payments" (PDF). Advances in Cryptology. Vol. 82. pp. 199–203. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0602-4_18. ISBN 978-1-4757-0604-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

Arvind Narayanan: What Happened to the Crypto Dream?, Part 1 Archived 2019-10-29 at the Wayback Machine. IEEE Security & Privacy. Volume 11, Issue 2, March–April 2013, pages 75-76, ISSN 1540-7993

Tschorsch, Florian, and Björn Scheuermann. 2016. “Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey on Decentralized Digital Currencies.” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 18 (3): 2084–2123.

Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). "The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and its mysterious inventor". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Marple T (2021). Bigger than Bitcoin: A Theoretical Typology and Research Agenda for Digital Currencies. Business and Politics 23, 439–455. source

NATHAN REIFF 2023, Can Crypto Be Hacked? By

Nakamoto, Satoshi. 2008. “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,” Working Paper, 9.

Halaburda, Hanna, and Neil Gandal. 2016. “Competition in the Digital Currency Market.” Working Paper. Available at SSRN2506463.

Hargreaves, Steve. 2013. “You Can Spend Bitcoins at Your Local Mall.” CNNMoney. Accessed 22 September 2020, source.

SEC, 2022 Case 1:22-cv-10501 Document 1 Filed 12/13/22 source

Cuthbertson, Anthony (17 October 2018). "What is tether? Controversial digital currency causes chaos for bitcoin price". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

Barontini, Christian, and Henry Holden. 2019. “Proceeding with Caution: A Survey on Central Bank Digital Currency.” BIS Paper (101).

Gronwald, Marc. 2019. “Is Bitcoin a Commodity? On Price Jumps, Demand Shocks, and Certainty of Supply.” Journal of International Money and Finance 97: 86–92.

Dell’Erba, Marco. 2019. “Stablecoins in Cryptoeconomics from Initial Coin Offerings to Central Bank Digital Currencies.” New York University Journal of Legislation & Public Policy 22: 1.

Golem. 2020. Golem Network. Accessed 23 September 2020, source.

Drezner, Daniel W. 2015. “Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance.” International Interactions 41 (4): 755–64.

Fenu, Gianni, Lodovica Marchesi, Michele Marchesi, and Roberto Tonelli. 2018. “The ICO Phenomenon and Its Relationships with Ethereum Smart Contract Environment.” 2018 International Workshop on Blockchain Oriented Software Engineering (IWBOSE). IEEE.

Broz, J. Lawrence; Frieden, Jeffry A. (2001). "The Political Economy of International Monetary Relations". Annual Review of Political Science. 4 (1): 317–343. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.317. ISSN 1094-2939.

Jani, Shailak. 2018. “An Overview of Ripple Technology and Its Comparison with Bitcoin Technology.” ResearchGate. source.

Yermack, David. 2015. “Is Bitcoin a Real Currency? An Economic Appraisal.” Handbook of Digital Currency. Elsevier.

O’Dwyer, Karl J., and David Malone. 2014. “Bitcoin Mining and Its Energy Footprint.” IET. Working paper.

Barry Eichengreen 2022 source

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。