AI= Cancer?

When most people are excited about the progress of AI, there is a group of people who have decided to resist AI.

In the past year, generative AI has made humans retreat in painting. Shi Lu, a game original painter with five years of experience, said that this year's changes are greater than any previous year. Many game development companies are using AI to reduce the size of the art team. Within a few months of AI's surge, the fees for original painters have dropped from 20,000 yuan per piece to 4,000 yuan per piece.

It has become a fact that some junior and intermediate-level original painters work for AI—most of the time, the first party generates more than 100 AI character images a day, while Shi Lu and her colleagues are responsible for retouching the images.

"Two weeks ago, I could still change the character's face or expression," Shi Lu said, "This week's task is to draw nose hair and blackheads." Years ago, when she was an intern, she could already draw game character images, but now "life is getting worse day by day." She believes that the culprit causing the difficult situation for painters is AI.

"That is cancer," she said. On the Internet, opponents have given the nickname "Cancer Brother" to those who support AI.

The contradiction between humans and AI is intensifying. Many artists are worried about AI infringement. They believe that the principle of generating images from text is "fragmented corpse splicing"—developers feed a large number of human-created paintings to the AI model, which breaks them up, then splices them together, and finally generates new images. (Although some technicians have come forward to refute this, it is of no avail.)

Opponents describe AI drawing as soulless, like a corpse, and liking AI drawing is "necrophilia." "Splicing theory" is their weapon, and from the perspective of ordinary people, the process of AI image generation has already involved infringement.

Large companies promoting AI are also embroiled in controversy.

On November 29, 2023, four artists jointly sued Xiaohongshu's AI model library for infringement, on the grounds that Xiaohongshu's AI image creation tool Trik is suspected of using their works to train AI models.

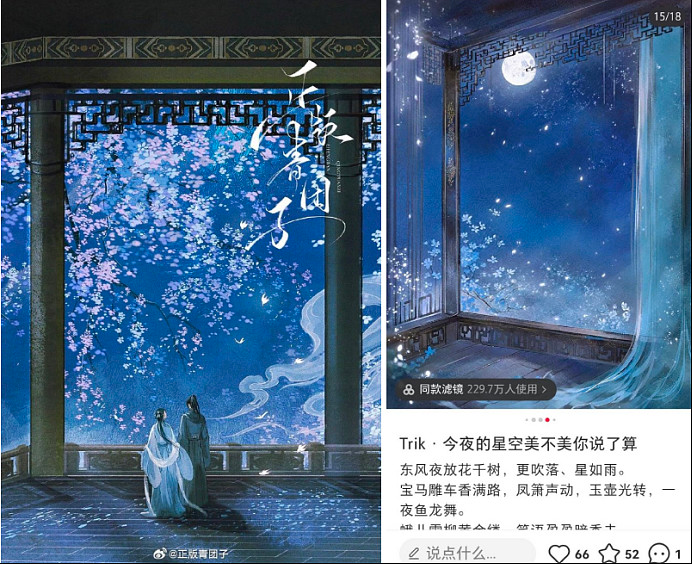

One of the artists, "Zhengban Qingtuanzi," posted two illustrations, one of her work and one of the Trik AI-generated image. "Whether it's the color elements or the visual style, it's very similar to my image, and it feels like my hard work has been plagiarized," she wrote. "I hope everyone can fight for their rights together."

A fan said that Trik AI's so-called Chinese-style images, "are fed a large number of works by the talented ladies in the ancient style community, and many (Trik) generated ancient-style scenes have a familiar feeling of the talented ladies." ("Talented ladies" is the nickname for talented artists in the community)

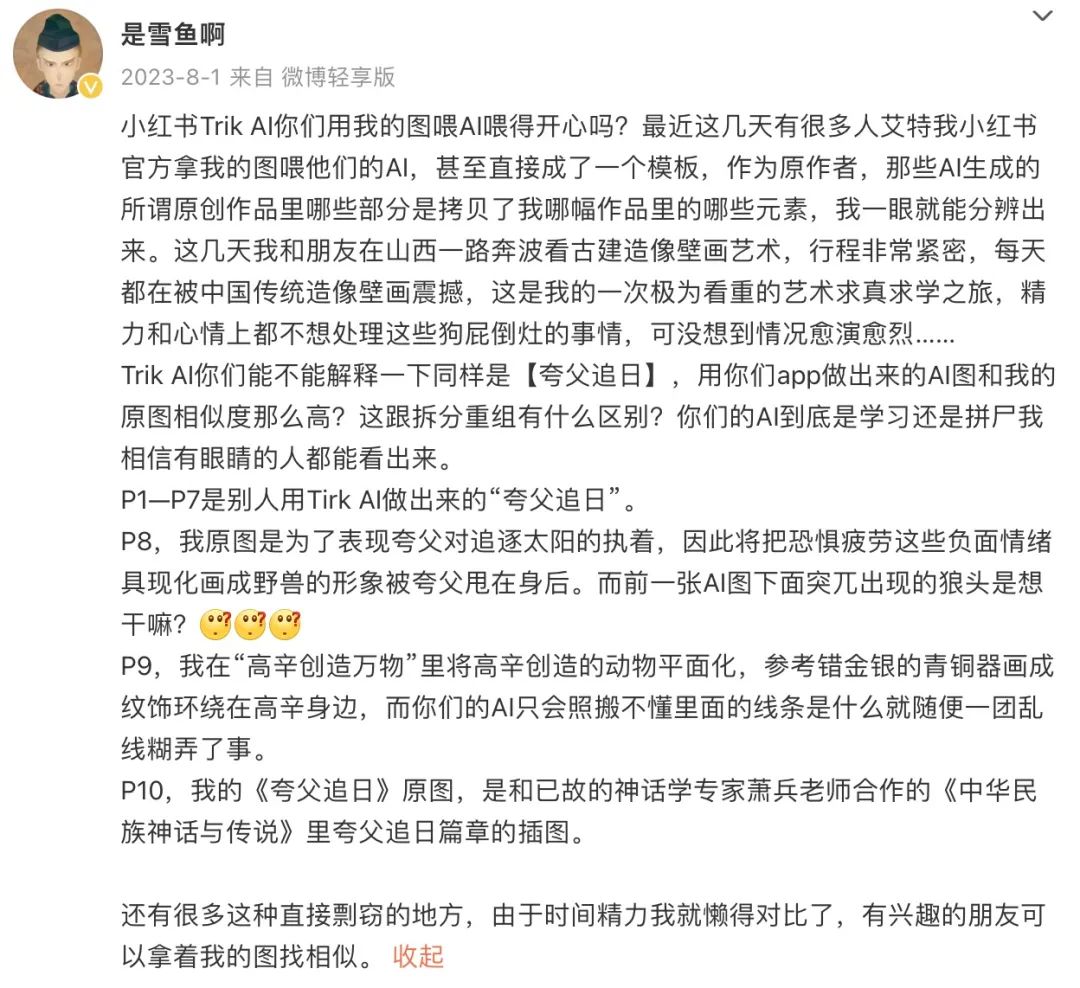

Illustrator "Shi Xueyu" compared the Trik AI-generated image with her own work and believed that the two were very similar, with similar elements. She called out to Xiaohongshu, "Are you happy to feed AI with my images?"

She announced that she would stop updating on Xiaohongshu, because Xiaohongshu used her works to feed AI without permission, and the platform's almost hegemonic user agreement made her uneasy.

The case against Xiaohongshu has been filed with the Beijing Internet Court. It is understood that this is the first case in China related to infringement of the AIGC training dataset.

Xiaohongshu refused to comment on the grounds that the case had entered the judicial process. Qingtuanzi revealed that before the case was filed, people from Xiaohongshu had approached them, hoping to negotiate. However, they had already agreed not to accept mediation and insisted on filing the case. Qingtuanzi said she hoped this case would provide a reference for copyright disputes in AI drawing.

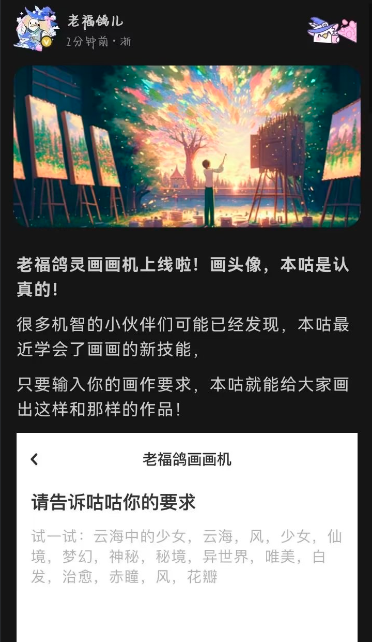

LOFTER, a platform under NetEase, is a common communication platform for artists and fans. Illustrator Gao Yue often shares her works on LOFTER and has accumulated a certain number of fans. Last year, she noticed that LOFTER was testing a new AI feature called "Laofuge Drawing Machine," which allows users to generate drawings using keywords. She couldn't help but suspect that the platform was secretly turning their works into AI training materials.

"I instantly lost trust in this platform and felt a chill down my spine," Gao Yue said.

Seeing more and more users expressing dissatisfaction, the official LOFTER deleted the announcement of the new feature a few days later and declared that the training data came from open source and did not use user data. However, the feature was not taken offline immediately, which was an important reason why users were not convinced and reassured.

After some struggle, Gao Yue chose to respond to the call of some creators, cleared her account, and then deactivated it, as a way of resistance. In Gao Yue's view, withdrawing from the platform is one of the few ways of self-protection.

"I don't want to publicly release my works to feed that monster that might replace me," she said.

The controversy in the designer community is growing. Last month, the mascot "Long Chenchen" for the Spring Festival Gala was also questioned as being AI-drawn—the number of toes on each dragon claw was different; the mouth hooked onto the nose; the dragon scales were sometimes single-layered and sometimes double-layered. The official Spring Festival Gala responded late at night on Weibo, "The designer's head is bald," and also shared the design process of the mascot.

Illustrator Ma Qun recalled that AI drawing was popular in 2022, and at that time, AI's drawings often failed, such as drawing people as dogs or horses, which was easy to recognize. Later, the speed of AI progress exceeded imagination, but there were still traces, such as AI still not knowing how to draw hands.

The bad news is that the above-mentioned loopholes gradually disappeared in a short period of time. Ma Qun believes that the identification of AI is increasingly relying on people's subjective feelings, "lacking spirituality," or "having a non-human quality."

Ma Qun also resists AI because AI has made her lose her passion for drawing. She did not come from a professional background, but learned drawing on her own with passion. After graduating from university, she became a full-time illustrator. The process of drawing is sometimes torturous, but the moment she sees the results, her joy surpasses everything.

And now, AI has erased most of the steps in drawing, everything is automated, which means that the skills and experience Ma Qun spent years learning pale in comparison to the efficient and powerful algorithms.

"Creation has become cheap," Ma Qun told 36Kr.

Going to Court

Creators have taken AI companies to court, almost throughout the year 2023.

In Silicon Valley, new technology trends are not uncommon. Previously, metaverse and cryptocurrency have received much attention but soon faded away. The reason why generative AI has caused a stir in a short period of time is because it seems genuinely useful, enough to disrupt the old world, and it is perceived as a huge threat, especially to content creators holding copyrights.

The first to challenge AI was an illustrator named Kara Ortiz. She is also a believer in the "splicing theory." Faced with the dominance of Stability AI in the field of painting, she could only think of two words: exploitation and disgust. During that time, some job opportunities were ruthlessly taken away by AI, causing her anxiety, and she decided to resist.

She sought help from lawyer Matthew Patrick. In the winter of 2022, Patrick provided legal assistance to a group of programmers who believed that Microsoft's GitHub Copilot was infringing on their copyrights. Patrick accused GitHub Copilot of "stealing the work of programmers" and actively prepared for the lawsuit. In January 2023, Patrick represented Ortiz in the lawsuit against Stability AI.

Similar lawsuits are not uncommon. Image company Getty Images sued Stability AI in the United States and the United Kingdom, accusing it of illegally copying and processing 12 million Getty Images; novelists led by George R.R. Martin and Jonathan Franzen challenged OpenAI, while a group of non-fiction writers targeted OpenAI and Microsoft; and Universal Music and other music labels claimed that Antropic illegally used their copyrighted works in the training process and illegally distributed lyrics in the model-generated content.

On December 27, 2023, The New York Times officially sued Microsoft and OpenAI, claiming that millions of articles from the newspaper were used as training data for AI, and AI is now competing with the newspaper as a news source.

A comprehensive legal battle over AI copyright has been launched, presenting numerous challenges to courts around the world.

In China, an AI drawing infringement case lasted for several months from filing to judgment, which is several times longer than the handling time of other image infringement cases.

In February 2023, the plaintiff Li Yunkai discovered in an article on Baijiahao that an image created by AI was used as an illustration without permission and with Li Yunkai's signature watermark removed. As a result, Li Yunkai sued the author for infringement of the right to attribution and the right to disseminate information over the internet at the Beijing Internet Court.

The case itself is not complicated, but because the infringed image was generated by the AI model Stable Diffusion, it attracted a lot of attention and was referred to by netizens as the "first case of AI drawing."

Li Yunkai is not a designer; he is an intellectual property lawyer with nearly 10 years of experience in the profession, during which he has been studying the game between new technology and copyright law. In September of last year, he began studying AI drawing tools and tried to generate images using Stable Diffusion, and also shared the AI-generated images on Xiaohongshu.

One day, Li Yunkai discovered that the image he created with AI appeared in an article on Baijiahao. This was a clear case of infringement. Out of professional interest, he wanted to understand the copyright ownership of AI-generated images and, more importantly, how the court would view it.

The person who appropriated Li Yunkai's image and is the defendant in this case is a woman in her fifties or sixties who claimed to be seriously ill and was bewildered when she received the court notice. In court, she explained that the image was obtained through an online search, and she could not provide the specific source.

She also argued that AI drawing is the crystallization of human wisdom and cannot be considered the work of the plaintiff. This is also the focus of the controversy in this case—whether the images generated by AI constitute works, and whether Li Yunkai has the copyright to the image.

For various countries, this is an unresolved legal issue. In August of last year, a court in the United States ruled that machine-generated content does not have copyright, on the grounds that "the identity of a human author is a basic requirement for copyright." However, this conclusion was quickly questioned. Some pointed out that using a machine, if you take a photo with a smartphone, the photo is protected by copyright; similarly, if you use an AI model to generate images, it should also be protected by copyright, shouldn't it?

In response to this issue, the Beijing Internet Court made a completely opposite judgment.

The judge presiding over the case required Li Yunkai to demonstrate in detail the entire process of generating images using AI, including downloading the software and writing prompts. In order to help the judge understand AI technology, Li Yunkai consulted a lot of information and tried his best to explain the principles and creative process of AI drawing to the judge.

The judge ultimately believed that Li Yunkai had made a lot of intellectual intervention in the creation process of the AI image in question, which demonstrated the originality of the work. Therefore, this AI image was recognized as Li Yunkai's work and enjoys copyright protection.

Li Yunkai told 36Kr that this judgment has left some AI companies in China "ambivalent." They are happy that AI-generated images have copyright, but worried that it seems the copyright belongs to the user.

AI companies, on the other hand, are seemingly unfazed by the copyright disputes. Objectively speaking, the resolution of copyright disputes is unlikely in the short term, so avoiding or maintaining silence is the most prudent approach.

In December 2023, Meitu Inc. launched a new generation of large models, claiming to have more powerful video generation capabilities. Although the company's senior management emphasized that AI is an auxiliary tool and not intended to replace professionals, many practitioners believe that these new features will eventually further threaten their job opportunities.

During the Q&A session, 36Kr raised the issue of potential copyright disputes caused by AI and inquired about how they would respond.

"The copyright issues of AIGC-generated images are subject to debate in practice and depend on further legal regulations," a senior executive said. "Although the current laws in this area are not very clear, we will generally protect the copyrights of users, especially professionals."

Another executive mentioned the judgment result of the "first case of AI drawing," expressing agreement with the court's decision, "In a situation like the 'first case of AI drawing,' we also believe that AI companies and AI models do not have relevant copyrights."

At the OpenAI Developer Conference this year, OpenAI made a high-profile announcement that they would bear the legal costs for those facing lawsuits for using GPT. However, some creators see this as a provocation.

To some extent, AI companies are confident. The core argument against AI— that AI models constitute infringement when using training data— is not unassailable. Some AI companies liken AI training to the learning process of humans, where a new apprentice needs to read and even imitate the works of their teacher to master the craft. If the court adopts this view, then it does not constitute infringement.

A lawyer stated that AI companies are likely to use the "fair use doctrine" as a defense. The "fair use doctrine" probably refers to the idea that although your actions strictly constitute infringement, your actions are a kind of acceptable borrowing used to promote creative expression. For example, scholars can quote excerpts from others' works in their own works; authors can publish adapted books; and ordinary people can excerpt movie clips for reviews.

In other words, if copyright restrictions are too strict, the creative power of civilization may stagnate.

Technology companies have long used this principle to avoid copyright disputes. In 2013, Google was sued by the Authors Guild for copying millions of books and uploading excerpts online. The judge ruled in favor of Google based on the fair use doctrine, stating that it created a searchable index for the public, creating public value.

In the era of large models, the fair use doctrine may still play a crucial role. Those who support AI not infringing on copyright believe that the process of generating content by large models is not much different from human creation—when you try to draw a picture or shoot a video, you will have images or movies you have seen in your mind. Human creativity progresses on the basis of predecessors, and large models do the same.

In the United States, there have been judges who have expressed support for Meta's position, rejecting the accusations of copyright infringement by writers against the text generated by LLaMA.

The judge hinted that the writers can continue to appeal, but this will prolong the litigation, which is also a positive development for AI companies. A scholar stated that as AI products become more popular, public acceptance of AI is increasing, which will require the courts to make more cautious judgments.

More importantly, the strategic position and commercial value of AI are constantly rising, and AI technology enthusiasts are generally concerned that overly strict copyright restrictions will hinder the development of AI technology.

Li Yunkai has communicated with some large model developers, and they indicated that the regulatory authorities are relatively cautious because, in addition to considering individual cases, they also need to consider the technological development of AI in China and the competition between countries in AI technology.

Another obstacle is that AI companies have almost no transparency in training data for models.

Just to give a recent example: On December 7, 2023, Google released a 60-page report, repeatedly emphasizing the criticality of training data—"We found that data quality is crucial for a high-performance model," but it provided almost no information about the source, screening, or specific content of the data.

An algorithm engineer told 36Kr that their ways of finding training data are nothing more than: crawling the content of the internet with a web crawler; finding some open-source datasets; and as a last resort, buying from the black market, "you can always find something to buy."

Some scholars have sarcastically remarked that instead of competing based on the performance scores of models in evaluation rankings, AI companies should compete to see who can have the most legitimate training data.

However, criticizing AI companies for their lack of transparency in training data is also somewhat unfair. After all, training data greatly influences model performance and is a trade secret of each AI company. Just imagine, Coca-Cola has strictly kept its formula a secret for 137 years, and no one has cracked it yet. AI companies will not easily reveal their trump cards.

Under existing legal provisions, AI companies also have no obligation or incentive to disclose training data.

Li Yunkai told 36Kr, "There is no evidence disclosure system in China" (this system stipulates that as long as the evidence is relevant to the facts of the case, the parties have the right to request other parties to present and disclose the evidence), which means that AI companies can choose not to disclose the training data of the model. "Under this system, as long as the company does not disclose, no one knows whether they have used user data for training. This is a deadlock," he said.

As of the time of writing, the cases of four artists suing Pionex AI have not yet gone to trial. Li Yunkai is following this case, and when it comes to victory or defeat, he said, "The demands of the artists may not receive support because they cannot prove that their works were used for training."

Unfortunately, it is highly unlikely for creators to achieve a complete victory in this copyright war.

But this does not mean that AI companies can completely disregard everything. Public opinion also matters. In November 2023, Kingsoft Office launched the public beta of its AI feature, and soon someone discovered that the product's privacy policy mentioned that to improve the accuracy of the AI feature, documents uploaded by users would be used as the basis for AI training after being de-identified. This clause caused a lot of user dissatisfaction.

A copyright lawyer speculated that the company's legal department included the above clause with the aim of "trying to make this matter as compliant as possible." After they avoided legal risks, they fell into public relations risks, which is somewhat darkly humorous.

A few days later, Kingsoft Office responded, promising that "all user documents will not be used for any AI training purposes," in order to quell the controversy. CEO Zhang Qingyuan said in an interview with "LatePost" that the clause was old, aimed at beautifying PPT templates, and did not involve user documents, and they did not have time to update it, leading to user misunderstanding.

Li Yunkai said that the definition of AI-related knowledge copyright can currently only be explored in judicial practice on a case-by-case basis. "The general consensus is to respect business practices, meaning that the law will not excessively intervene in the autonomous actions of companies. If there is intellectual property, the general principle is that it belongs to the developers for distribution."

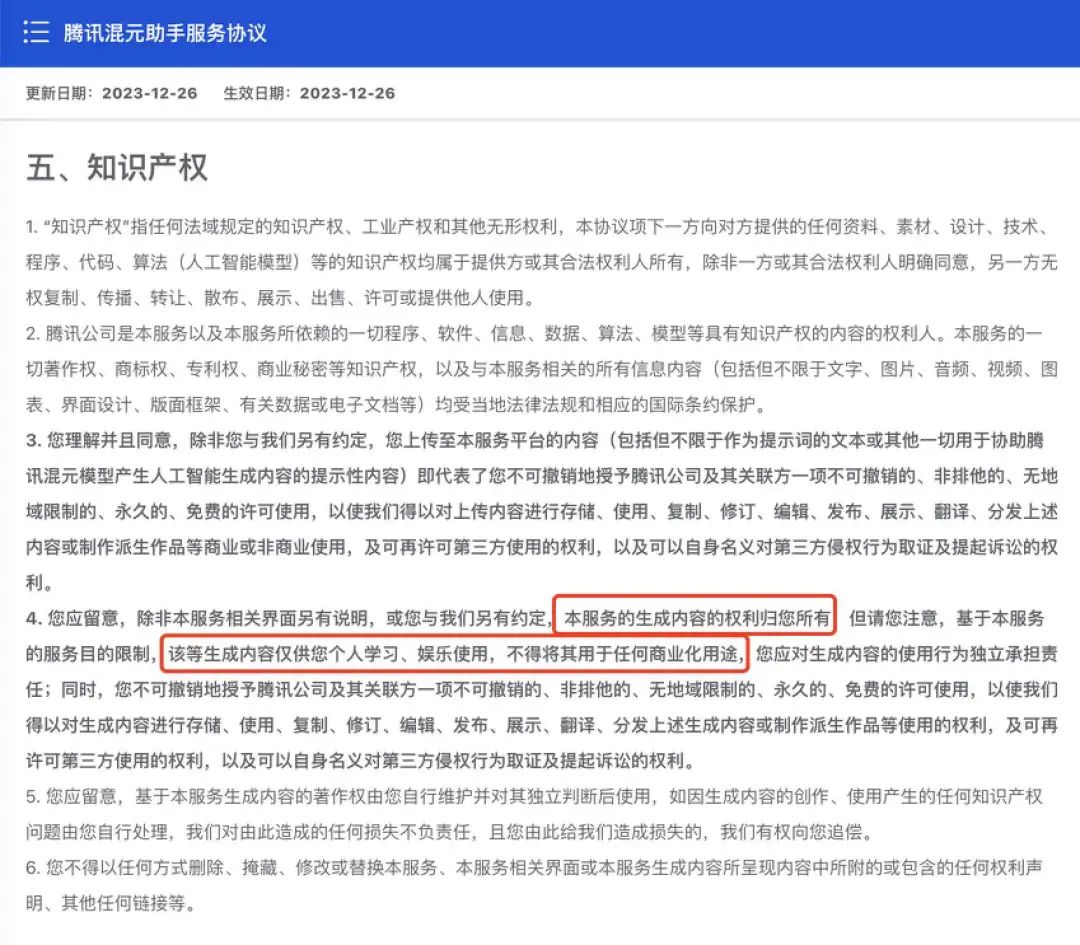

Tencent's mixed-element model stipulates in its relevant terms that the copyright of the generated content belongs to the user, but "is only for personal learning and entertainment use, and may not be used for any commercial purposes." Li Yunkai said, "Other companies are not so generous."

Currently, a compromise solution with a loud voice is that AI companies should have a solution to compensate content creators (similar to Spotify's compensation for musicians). If a work is used as AI training data, the creator can receive a certain fee. In the short term, this will protect the interests of creators. As for what will happen in the longer term, no one can guarantee.

2023 has been called the "Summer of AI," and AI companies have successfully made more people believe that AI is the trend, including some content creators. Not long ago, Zhang Lixian, the editor-in-chief of "Duku," stated on Weibo that the magazine's cover images for 2024 will all be created using AI drawing.

A illustrator commented, "The quality-focused 'Duku' accepting AI artwork is meaningful."

△ Relevant terms of the mixed-element model (Image source: screenshot)

These are the translated results.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。