Over the past decade, the crypto world has spent a significant amount of time proving that it is not a Ponzi scheme; in the next decade, it needs to demonstrate with the same determination that it is secure enough to support serious capital.

Written by: On-Chain Revelation

By 2025, the crypto industry appears to be "much more mature" than it was a few years ago: contract templates are more standardized, auditing firms are lining up, and AI features are gradually appearing in various security tools. On the surface, risks seem to be orderly compressed.

However, what is truly changing is the structure of attacks.

The number of on-chain vulnerabilities is decreasing, but a single incident can still wipe out an entire institution's balance sheet; AI is currently mainly used as a simulation and auditing tool, but it is quietly changing the iteration speed of attack scripts; meanwhile, on the off-chain side, state-sponsored hackers are starting to use remote recruitment, freelance platforms, and corporate collaboration software as new battlegrounds.

In other words, security issues are no longer just about "whose code is cleaner," but rather "whose system can withstand misuse and infiltration." For many teams, the biggest risks are not on-chain, but in the layers they do not truly consider as security issues: accounts and permissions, personnel and processes, and how these elements fail under pressure.

This article attempts to provide a simplified map for 2026: from on-chain logic, to accounts and keys, and then to teams, supply chains, and post-incident responses— the security issues the crypto industry faces are evolving from a "vulnerability list" into a set of actionable frameworks that must be implemented.

1. On-Chain Attacks: Fewer, but More Expensive

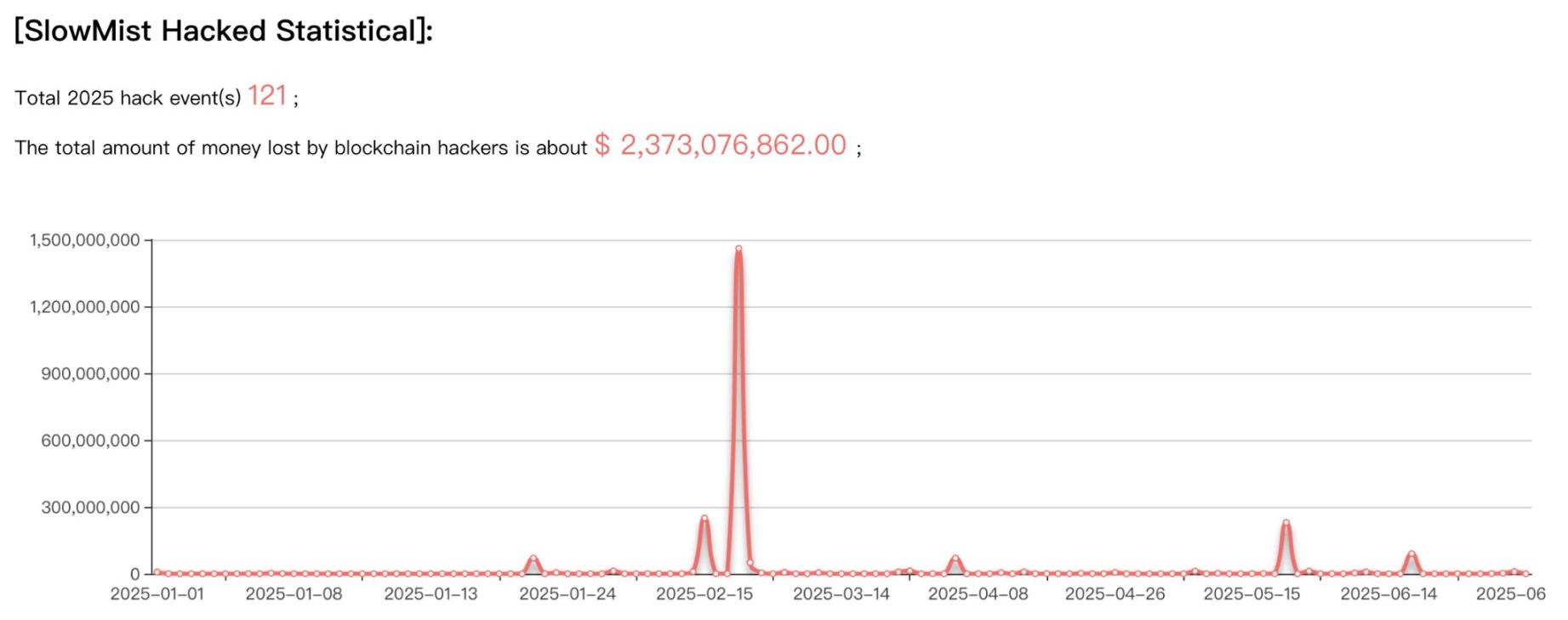

This year's crypto attacks exhibit a new symmetry: the number of incidents is decreasing, but the destructiveness of each attack has significantly increased. SlowMist's mid-2025 report shows that the crypto industry encountered 121 security incidents in the first half of the year—down 45% from 223 in the same period last year. This should be good news, but the losses from attack incidents skyrocketed from $1.43 billion to approximately $2.37 billion, an increase of 66%.

Attackers are no longer wasting time on low-value targets, but are focusing on high-value assets and high-tech barriers.

Source: SlowMist Mid-2025 Report

DeFi: From Low-Cost Arbitrage to High-Tech Games

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) remains the primary battleground for attackers, accounting for 76% of attack incidents. However, despite the high number of incidents totaling 92, the losses from DeFi protocols decreased from $659 million in 2024 to $470 million. This trend indicates that the security of smart contracts is gradually improving, with the proliferation of formal verification, bug bounty programs, and runtime protection tools building a stronger defense for DeFi.

But this does not mean that DeFi protocols are safe. Attackers are shifting their focus to more complex vulnerabilities, seeking opportunities that can yield greater returns. Meanwhile, centralized exchanges (CEX) have become the main source of losses. Although only 11 attack incidents occurred, they caused losses of up to $1.883 billion, with a single loss from a well-known exchange reaching $1.46 billion—one of the largest single attack incidents in crypto history (even surpassing the $625 million Ronin incident). These attacks do not rely on on-chain vulnerabilities but stem from account hijacking, internal permission abuse, and social engineering attacks.

The data disclosed in this report tells a clear story: centralized exchanges (CEX) have generated higher total losses despite being attacked far less frequently than DeFi. On average, the "return" from attacking a CEX is over 30 times that of attacking a DeFi protocol.

This "efficiency gap" has also led to a polarization of attack targets:

- DeFi Battleground: Technology Intensive—attackers need to deeply understand smart contract logic, discover reentrancy vulnerabilities, and exploit AMM pricing mechanism flaws;

- CEX Battleground: Permission Intensive—the goal is not to crack code, but to gain access to accounts, API keys, and multi-signature wallet signing rights.

At the same time, attack methods are evolving. In the first half of 2025, a series of new attacks emerged: phishing attacks utilizing the EIP-7702 authorization mechanism, investment scams using deepfake technology to impersonate exchange executives, and malicious browser plugins disguised as Web3 security tools. A deepfake scam gang uncovered by Hong Kong police caused losses exceeding HKD 34 million—victims believed they were video calling real cryptocurrency influencers, while in reality, the other party was an AI-generated virtual image.

Description: AI-generated virtual image

Hackers are no longer casting a wide net; they are hunting for great white sharks.

2. AI: A Defensive Tool and an Offensive Multiplier

If on-chain attacks are becoming more specialized and focused on a few high-value targets, then the emergence of cutting-edge AI models provides attackers with the technical possibility to scale and automate these attacks.

A recent study on December 1 indicates that in blockchain simulation environments, AI agents can complete the entire attack chain from smart contract vulnerability analysis, exploitation construction, to fund transfer.

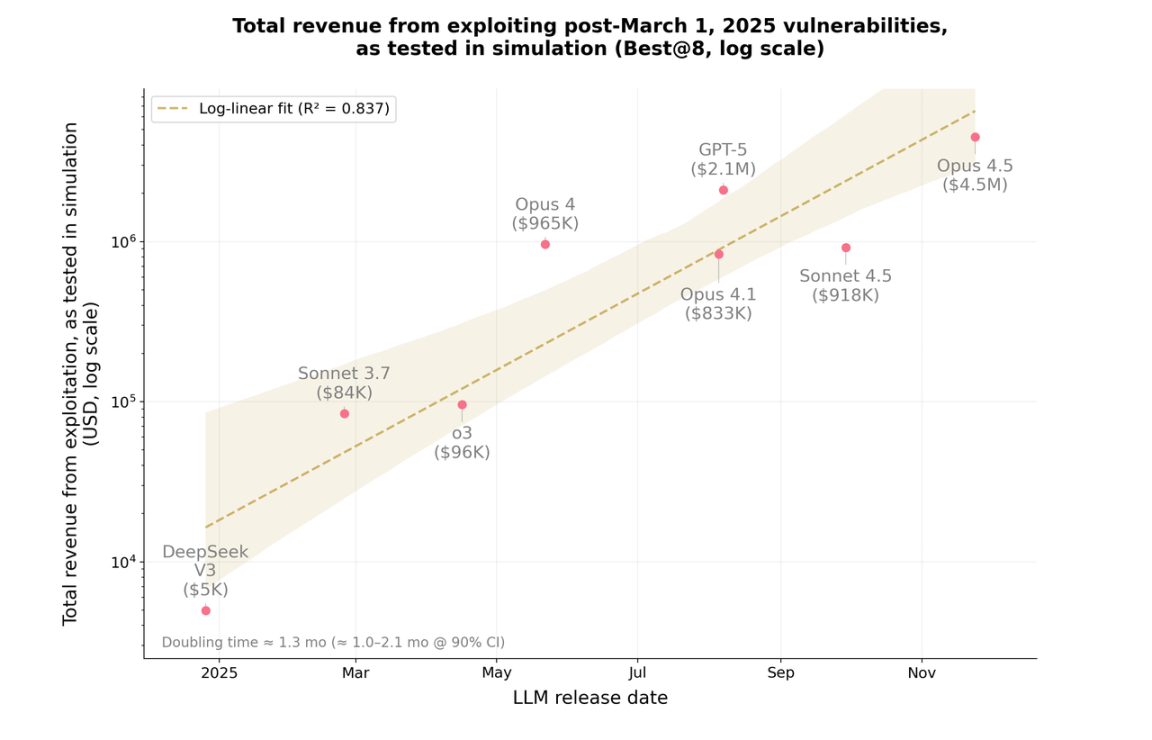

In an experiment led by the MATS and Anthropic teams, AI models (such as Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT-5) successfully exploited real-world smart contract vulnerabilities, "stealing" approximately $4.6 million in assets in a simulated environment. More strikingly, among 2,849 newly deployed contracts with no public vulnerability records, these models uncovered two zero-day vulnerabilities and completed simulated attacks worth $3,694 at an API cost of about $3,476.

In other words, the average cost of scanning a contract for vulnerabilities is only about $1.22, which is lower than the price of a subway ticket.

AI is also learning to "do the math." In a vulnerability scenario named FPC, GPT-5 "stole" $1.12 million, while Claude Opus 4.5 siphoned off $3.5 million—the latter systematically attacked all liquidity pools that reused the same vulnerability pattern, rather than settling for a single target; this proactive pursuit of "maximizing returns" in attack strategies was previously seen as a skill of human hackers.

Description: Total earnings from AI model exploiting vulnerabilities (based on simulation tests). Source: Anthropic

More importantly, the research team deliberately controlled for data contamination: they selected 34 contracts that were attacked in reality only after March 2025 (the cutoff date for the models' knowledge) as the test set. Even so, the three models successfully exploited 19 of them in the simulated environment, collectively "stealing" about $4.6 million. This is not a whiteboard exercise, but a complete set of attack script prototypes that can be directly transplanted to real blockchains; under the premise that the contracts and on-chain states remain unchanged, they are sufficient to translate into real monetary losses.

Exponentially Growing Attack Capabilities

The same study also presents a more uncomfortable conclusion: in the 2025 sample, the "vulnerability mining returns" of AI double approximately every 1.3 months—this growth rate is an order of magnitude faster than Moore's Law. With rapid advancements in reasoning, tool invocation, and long-cycle task execution, defenders are clearly losing their time advantage.

In this environment, the question is no longer whether AI will be used to attack, but what critical risks the blockchain industry will face if it fails to properly address AI-driven security challenges.

Tat Nguyen, founder of the blockchain autonomous AI security company VaultMind, succinctly summarizes this risk point:

For blockchain, the most critical risk is speed. Microsoft's latest defense report has shown that AI can automate the entire attack lifecycle. If we cannot adapt quickly, the blockchain industry will face "machine-level speed" attacks—vulnerability exploitation will shift from weeks to seconds. Traditional audits often take weeks, and even so, about 42% of the hacked protocols had been audited. The answer is almost inevitable: a continuous, AI-driven security system.

For the crypto industry, the implications are straightforward: by 2025, AI is no longer just a placebo for defenders; it has become a core force in the attack chain. This also means that the security paradigm itself must be upgraded, not just "doing a few more audits."

3. From On-Chain Vulnerabilities to Resume Infiltration: The Evolution of State Hackers

If the emergence of AI represents a technological upgrade, then the infiltration by North Korean hackers raises the risk dimension to a more uncomfortable height.

North Korean hacker organizations (such as Lazarus) have become one of the main threats in the crypto industry, shifting their focus from directly attacking on-chain assets to long-term and covert off-chain infiltration.

North Korean Hackers' "Job Seeker" Strategy

AI is upgrading the attackers' toolbox, while North Korean hackers are raising the risk dimension to a more uncomfortable height. Rather than being a technical issue, this is a concentrated test of organizational and personnel security bottom lines. Relevant hacker organizations (such as Lazarus) have become one of the main threats in the crypto industry, focusing on long-term and covert off-chain infiltration rather than direct attacks on on-chain assets.

The "job seeker" strategy of North Korean hackers

At the Devconnect conference in Buenos Aires, Web3 security expert and Opsek founder Pablo Sabbatella provided a set of eye-opening estimates: 30%–40% of job applications in the crypto industry may come from North Korean agents. If this estimate is even half accurate, the recruitment inboxes of crypto companies are no longer just talent markets; they resemble new attack vectors.

The "job seeker strategy" they employ is not complex, but it is effective enough: disguising themselves as remote engineers, they enter a company's internal systems through normal recruitment processes, targeting code repositories, signing permissions, and multi-signature seats. In many cases, the actual operators do not directly expose their identities but recruit "agents" through freelance platforms in countries like Ukraine and the Philippines: agents rent out their verified accounts or identities, allowing the other party to remotely control devices, with income shared as agreed—keeping about 20% for themselves, while the rest goes to North Korea.

When targeting the U.S. market, the disguise often adds another layer. A common arrangement is to first find an American to act as a "front end," claiming to be a "Chinese engineer who doesn't speak English" and needing someone to attend interviews on their behalf. Subsequently, they infect this "front end's" computer with malware, borrowing its U.S. IP and broader network access. Once successfully employed, these "employees" work long hours, produce stable output, and almost never complain, making them less suspicious in a highly distributed team.

The effectiveness of this strategy relies not only on North Korean resources but also exposes structural gaps in the crypto industry's operational security (OPSEC): remote work has become the default option, teams are highly decentralized across multiple jurisdictions, and recruitment verification processes are often lax, with a much greater emphasis on technical skills than background checks.

In such an environment, a seemingly ordinary remote job resume may be more dangerous than a complex smart contract. When attackers are already sitting in your Slack channel, have GitHub access, and even participate in multi-signature decisions, no matter how perfect the on-chain audit is, it can only cover part of the risk.

This is not an isolated incident but part of a larger picture. A report released by the U.S. Treasury Department in November 2024 estimated that North Korean-related hackers have stolen over $3 billion in crypto assets over the past three years, some of which have been used to support Pyongyang's nuclear and missile programs.

For the crypto industry, this means that a "successful attack" is never just a digital game on-chain; it can directly alter military budgets in the real world.

4. From Risk Lists to Action Lists: The Security Baseline for 2026

The previous sections have clearly presented the three major threats facing the crypto industry: AI-driven machine-level attacks, systemic failures of auditing systems, and infiltration by state actors like North Korea. When these risks overlap, traditional security frameworks reveal fatal shortcomings.

This section will answer the only important question: what kind of security architecture does a crypto project need in the new threat environment?

A security architecture more suitable for 2026 should include at least the following five layers:

- Smart contracts and on-chain logic that can be continuously monitored and automatically regression tested;

- An identity system designed to treat keys, permissions, and accounts as "high-value attack surfaces";

- An organizational and personnel security system focused on preventing state-level infiltration and social engineering attacks (covering recruitment and security drills);

- AI countermeasures built into the infrastructure, rather than temporary add-ons;

- A response system capable of tracing, isolating, and protecting assets within minutes in the event of an incident.

The real change lies in transforming security from a one-time contract acceptance into a continuously operating infrastructure—much of this capability will inevitably exist in the form of "AI security as a service."

Layer One: On-Chain Logic and Smart Contract Security

This layer primarily applies to DeFi protocols, core wallet contracts, cross-chain bridges, and liquidity protocols. The issues addressed at this layer are straightforward: once code is on-chain, errors are usually irreversible, and the cost of fixing them is much higher than traditional software.

In practice, several approaches are becoming foundational configurations for such projects:

Introduce AI-assisted pre-deployment audits, rather than just static checks.

- Before formal deployment, use publicly available security benchmarking tools or AI adversarial auditing frameworks to conduct systematic "attack simulations" on the protocol, focusing on multi-path, combinatorial calls, and boundary conditions, rather than just scanning for single-point vulnerabilities.

Conduct pattern-based scanning of similar contracts to reduce the probability of "batch failures."

- Establish pattern-based scanning and baselines on reusable templates, pools, and strategy contracts to batch identify "homogeneous vulnerabilities" that may arise under the same development model, preventing a single mistake from compromising multiple pools simultaneously.

Maintain a minimal upgrade scope and ensure multi-signature structures are sufficiently transparent.

- The upgrade surface of management contracts should be strictly limited, retaining only necessary adjustment space. At the same time, multi-signature and permission structures need to be explainable to the community and key partners to reduce the governance risk of "technical upgrades being viewed as a black box."

Continuously monitor for potential manipulation behaviors after deployment, rather than just focusing on price.

On-chain monitoring should not only observe price and oracle anomalies but also cover:

- Abnormal changes in authorization events;

- Batch abnormal calls and concentrated permission operations;

- Sudden appearances of abnormal fund flows and complex call chains.

If this layer is not handled properly, subsequent permission management and post-incident responses can only aim to minimize losses under chaotic conditions, making it difficult to prevent the occurrence of incidents themselves.

Layer Two: Account, Permission, and Key System Security (Core Risks for CEX and Wallets)

For centralized services, the security of account and key systems often determines whether an incident escalates to a "survival-level risk." Recent cases involving exchanges and custodians indicate that significant asset losses occur more at the account, key, and permission system level than from simple contract vulnerabilities.

At this layer, several basic practices are becoming industry consensus:

- Eliminate shared accounts and generic management backend accounts, binding all critical operations to accountable personal identities;

- Use MPC or equivalent multi-party control mechanisms for key operations like withdrawals and permission changes, rather than relying on a single key or single approver;

- Prohibit engineers from directly handling sensitive permissions and keys on personal devices; related operations should be restricted to controlled environments;

- Implement continuous behavioral monitoring and automated risk scoring for core personnel, providing timely alerts for signals such as abnormal login locations and unusual operational rhythms.

- For most centralized institutions, this layer serves as the main battleground to prevent internal errors and malfeasance, as well as the last barrier to stop a security incident from evolving into a "survival-level event."

Layer Three: Organizational Security & Personnel Security (Blocking Layer for State-Level Infiltration)

In many crypto projects, this layer is almost blank. However, by 2025, the importance of organizational and personnel security can be placed on par with the security of contracts themselves: attackers do not necessarily need to breach the code; infiltrating teams is often cheaper and more stable.

As state-level actors increasingly utilize the "remote job + agents + long-term infiltration" strategy, project teams need to address shortcomings in at least three areas.

First, reconstruct the recruitment and identity verification processes.

The recruitment process needs to upgrade from "formally reviewing resumes" to "substantive verification" to reduce the probability of long-term infiltration, such as:

- Requiring real-time video communication instead of just voice or text exchanges;

- Requiring real-time screen sharing during technical interviews and coding tests to prevent "proxy coding";

- Conducting cross-references on educational backgrounds, previous companies, and former colleagues;

- Verifying candidates' long-term technical trajectories against activities on GitHub, Stack Overflow, etc.

Second, limit single-point permissions to avoid a one-time "full green light."

New engineers should not have direct access to key systems, signing infrastructure, or production-level databases in a short time; permissions should be gradually elevated and tied to specific responsibilities. The design of internal systems should also be layered and isolated to prevent any single position from inherently possessing "full-link permissions."

Third, treat core positions as higher-priority social engineering attack surfaces.

In many attacks, frontline operations and infrastructure personnel are often easier targets than the CEO, including:

- DevOps / SRE;

- Signing administrators and key custodians;

- Wallet and infrastructure engineers;

- Audit engineers and red team members;

- Cloud and access control administrators.

For these positions, regular social engineering attack drills and security training are no longer "bonus items" but necessary conditions to maintain basic defenses.

If this layer is not handled well, no matter how complex the technical defenses of the first two layers are, they can easily be bypassed by a carefully designed recruitment process or a seemingly normal remote collaboration.

Layer Four: AI Security Countermeasures (Emerging Defense Layer)

Once high-level attackers begin systematically using AI, defenders relying on "manual analysis + audits every six months" are essentially pitting human effort against automated systems, with limited chances of success.

A more pragmatic approach is to incorporate AI into the security architecture in advance, forming normalized capabilities in at least the following areas:

- Before formal deployment, use AI for "adversarial audits" to systematically simulate multi-path attacks;

- Scan similar contracts and comparable development models to identify "vulnerability families" that appear in batches;

- Integrate logs, behavioral patterns, and on-chain interaction data to establish risk scoring and prioritization using AI;

- Identify and intercept deepfake interviews and abnormal interview behaviors (such as voice delays, mismatched eye and mouth movements, overly scripted responses, etc.);

- Automatically discover and block the download and execution of malicious plugins and malicious development toolchains.

If this direction continues to evolve, AI is likely to become a new infrastructure layer in the security industry by 2026:

Security capabilities will no longer be proven by "a piece of audit report," but rather measured by whether defenders can leverage AI to discover, alert, and respond at speeds close to that of machines.

After all, once attackers start using AI, if defenders continue to operate on a "semi-annual audit" rhythm, they will soon be overwhelmed by the pace of attacks.

Layer Five: Post-Incident Response and Asset Freezing

In on-chain security, the ability to recover funds after an incident has become an independent battleground. By 2025, asset freezing is one of the most important tools in this battleground.

Public data signals are quite clear: SlowMist's "2025 Mid-Year Blockchain Security and Anti-Money Laundering Report" shows that the total amount stolen on-chain in the first half of the year was approximately $1.73 billion, of which about $270 million (approximately 11.38%) was frozen or recovered, already a relatively high level in recent years.

The speed of a project's response after an attack largely determines the proportion of recoverable assets. Therefore, at this layer, the industry needs to establish a "wartime mechanism" in advance, rather than making up for it after an incident occurs:

- Establish a rapid response mechanism with professional on-chain monitoring and security service organizations, including technical alert channels (Webhook / emergency groups) and clear disposal SLAs (response time in minutes, action recommendations in hours);

- Pre-design and rehearse emergency multi-signature processes for quickly enabling or disabling contracts and freezing high-risk functions;

- Set up automatic pause mechanisms for cross-chain bridges and other critical infrastructure: when anomalies occur in fund flows, call frequencies, and other indicators, the system automatically enters shutdown or read-only mode.

* As for further asset recovery, it often needs to extend off-chain: including establishing compliance and legal collaboration pathways with stablecoin issuers, custodians, and major centralized platforms.

Defense is no longer just about "avoiding attacks," but about minimizing the final losses and spillover effects after an attack as much as possible.

Conclusion: Security is a New Admission Ticket

The current reality is that most crypto projects only cover one or two layers of the five security levels. This is not a matter of technical capability but a choice of priorities: visible short-term gains often outweigh the invisible long-term construction.

However, after 2025, the threshold for attacks is shifting from "scale" to "relevance." AI tools have made low-cost reconnaissance the norm, and the core issue of security has become: when the real impact arrives, can the system still maintain operation?

Projects that can smoothly navigate through 2026 may not necessarily be the most technically radical, but they will certainly have systematic defenses across these five dimensions. The next round of systemic events will partly determine whether the crypto industry continues to be viewed as a high-risk asset pool or is seriously considered as a candidate for financial infrastructure.

Over the past decade, the crypto world has spent a lot of time proving it is not a Ponzi scheme; in the next decade, it needs to demonstrate with the same determination that it can support serious capital in terms of security. For truly long-term funds, this will be one of the dividing lines for continued participation.

"In the long run, the most dangerous risk is the one you refuse to see."

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。