撰文:深潮 TechFlow

市场反弹了,但交易所又被盗了。

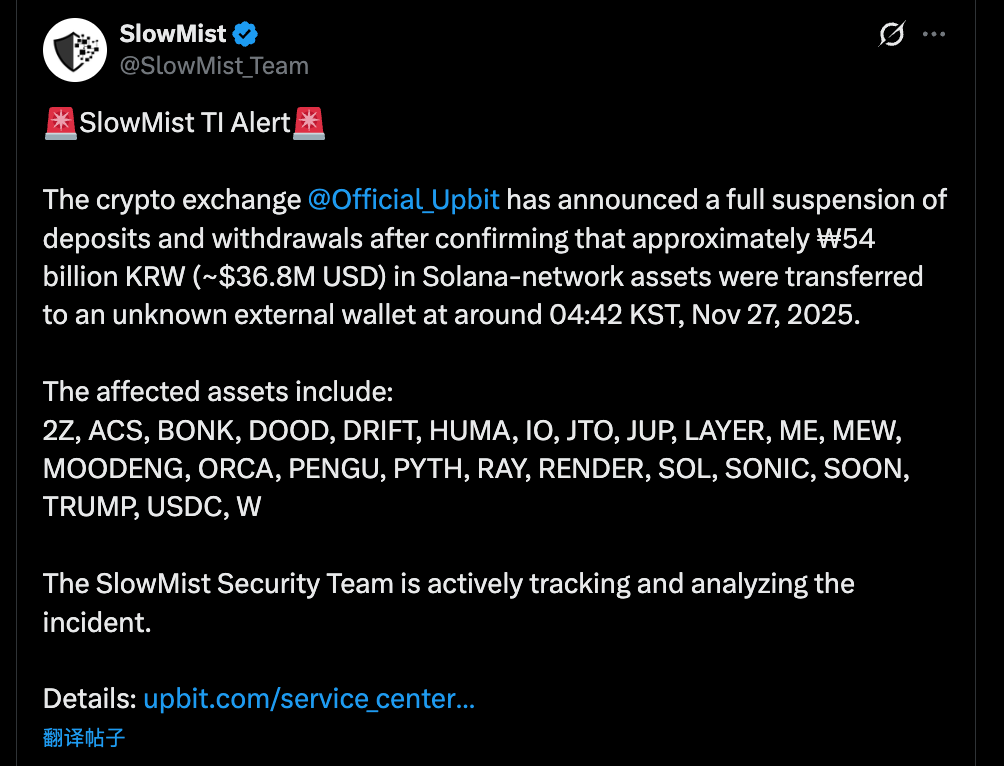

11 月 27 日,韩国最大的加密货币交易所 Upbit 确认发生安全漏洞,导致价值约 540 亿韩元(约 3680 万美元)的资产流失。

首尔时间 11 月 27 日凌晨 04:42(KST),当大多数韩国交易员还在沉睡时,Upbit 的 Solana 热钱包地址出现了异常的大规模资金流出。

据慢雾等安全机构的链上监测数据,攻击者并未采取单一资产转移的方式,而是对 Upbit 在 Solana 链上的资产进行了“清空式”掠夺。

被盗资产不仅包含核心代币 SOL 和稳定币 USDC,还覆盖了 Solana 生态内几乎所有主流的 SPL 标准代币。

被盗资产清单(部分):

-

DeFi/基础设施类:JUP (Jupiter), RAY (Raydium), PYTH (Pyth Network), JTO (Jito), RENDER, IO 等。

-

Meme/社区类:BONK, WIF, MOODENG, PENGU, MEW, TRUMP 等。

-

其他项目:ACS, DRIFT, ZETA, SONIC 等。

这种一锅端的特征表明,攻击者极有可能获取了 Upbit 负责 Solana 生态热钱包的私钥权限,或者是签名服务器(Signing Server)遭到了直接控制,导致其能够对该钱包下的所有 SPL 代币进行授权转移。

对于 Upbit 这家占据韩国 80% 市场份额、以拥有韩国互联网振兴院(KISA)最高安全等级认证为傲的巨头来说,这无疑是一次惨痛的“破防”。

不过,这也不是韩国交易所第一次被盗了。

如果将时间轴拉长,我们会发现韩国加密市场在过去八年里,实际上一直在被黑客,尤其是朝鲜黑客光顾。

韩国加密市场,不仅是全球最疯狂的散户赌场,也是北朝鲜黑客最顺手的“提款机”。

八年朝韩攻防,被盗编年史

从早期的暴力破解到后来的社会工程学渗透,攻击手段不断进化,韩国交易所的受难史也随之延长。

累计损失:约2亿美元(按被盗时价格;若按当前价格计算超过12亿美元,其中仅2019年Upbit被盗的34.2万枚ETH现值已超10亿美元)

-

2017:蛮荒时代,黑客从员工电脑下手

2017 年是加密牛市的起点,也是韩国交易所噩梦的开始。

这一年,韩国最大的交易所 Bithumb 率先「中招」。6 月,黑客入侵了一名 Bithumb 员工的个人电脑,窃取了约 31,000 名用户的个人信息,随后利用这些数据对用户发起定向钓鱼攻击,卷走约 3200 万美元。事后调查发现,员工电脑上存储着未加密的客户数据,公司甚至没有安装基本的安全更新软件。

这暴露了当时韩国交易所安全管理的草台状态,连「不要在私人电脑存客户数据」这种常识都没有建立。

更具标志性意义的是中型交易所 Youbit 的覆灭。这家交易所在一年内遭受了两次毁灭性打击:4 月份丢失近 4000 枚比特币(约 500 万美元),12 月再次被盗走 17% 的资产。不堪重负的 Youbit 宣布破产,用户只能先提取 75% 的余额,剩余部分需等待漫长的破产清算。

Youbit 事件后,韩国互联网安全局(KISA)首次公开指控朝鲜是幕后黑手。这也向市场发出了一个信号:

交易所面对的不再是普通网络窃贼,而是有着地缘政治目的的国家级黑客组织。

-

2018:热钱包大劫案

2018 年 6 月,韩国市场经历了连续重创。

6 月 10 日,中型交易所 Coinrail 遭遇袭击,损失超过 4000 万美元。与此前不同,这次黑客主要掠夺的是当时火热的 ICO 代币(如 Pundi X 的 NPXS),而非比特币或以太坊。消息传出后,比特币价格短时暴跌超过 10%,整个加密市场在两天内蒸发超过 400 亿美元市值。

仅仅十天后,韩国头部交易所 Bithumb 也宣告失守,热钱包被盗走约 3100 万美元的 XRP 等代币。讽刺的是,攻击发生前几天,Bithumb 刚在推特上宣布正在「将资产转移至冷钱包以升级安全系统」。

这是 Bithumb 一年半内第三次被黑客「光顾」。

「连环爆雷」严重打击了市场信心。事后,韩国科技部对国内 21 家交易所进行安全审查,结果显示只有 7 家通过全部 85 项检查,剩余 14 家「随时可能暴露于黑客攻击风险中」,其中 12 家在冷钱包管理方面存在严重漏洞。

-

2019:Upbit 的 342,000 枚 ETH 被盗

2019 年 11 月 27 日,韩国最大交易所 Upbit 遭遇了当时国内史上最大规模的单笔盗窃。

黑客利用交易所整理钱包的间隙,单笔转走了 342,000 枚 ETH。他们没有立即砸盘,而是通过「剥离链」(Peel Chain)技术,将资金拆解成无数笔小额交易,层层转移,最终流入数十家非 KYC 交易所和混币器。

调查显示,57% 的被盗 ETH 以低于市场价 2.5% 的折扣在疑似朝鲜运营的交易所兑换成比特币,剩余 43% 通过 13 个国家的 51 家交易所洗白。

直到五年后的 2024 年 11 月,韩国警方才正式确认该案系朝鲜黑客组织 Lazarus Group 和 Andariel 所为。调查人员通过 IP 追踪、资金流向分析,以及攻击代码中出现的朝鲜特有词汇「흘한 일」(意为「不重要」)锁定了攻击者身份。

韩国当局与美国 FBI 合作追踪资产,历经四年司法程序,最终从瑞士一家交易所追回 4.8 枚比特币(约 6 亿韩元),并于 2024 年 10 月归还 Upbit。

不过相比被盗总额,这点追回几乎可以忽略不计。

-

2023:GDAC 事件

2023 年 4 月 9 日,中型交易所 GDAC 遭遇攻击,损失约 1300 万美元——占其托管总资产的 23%。

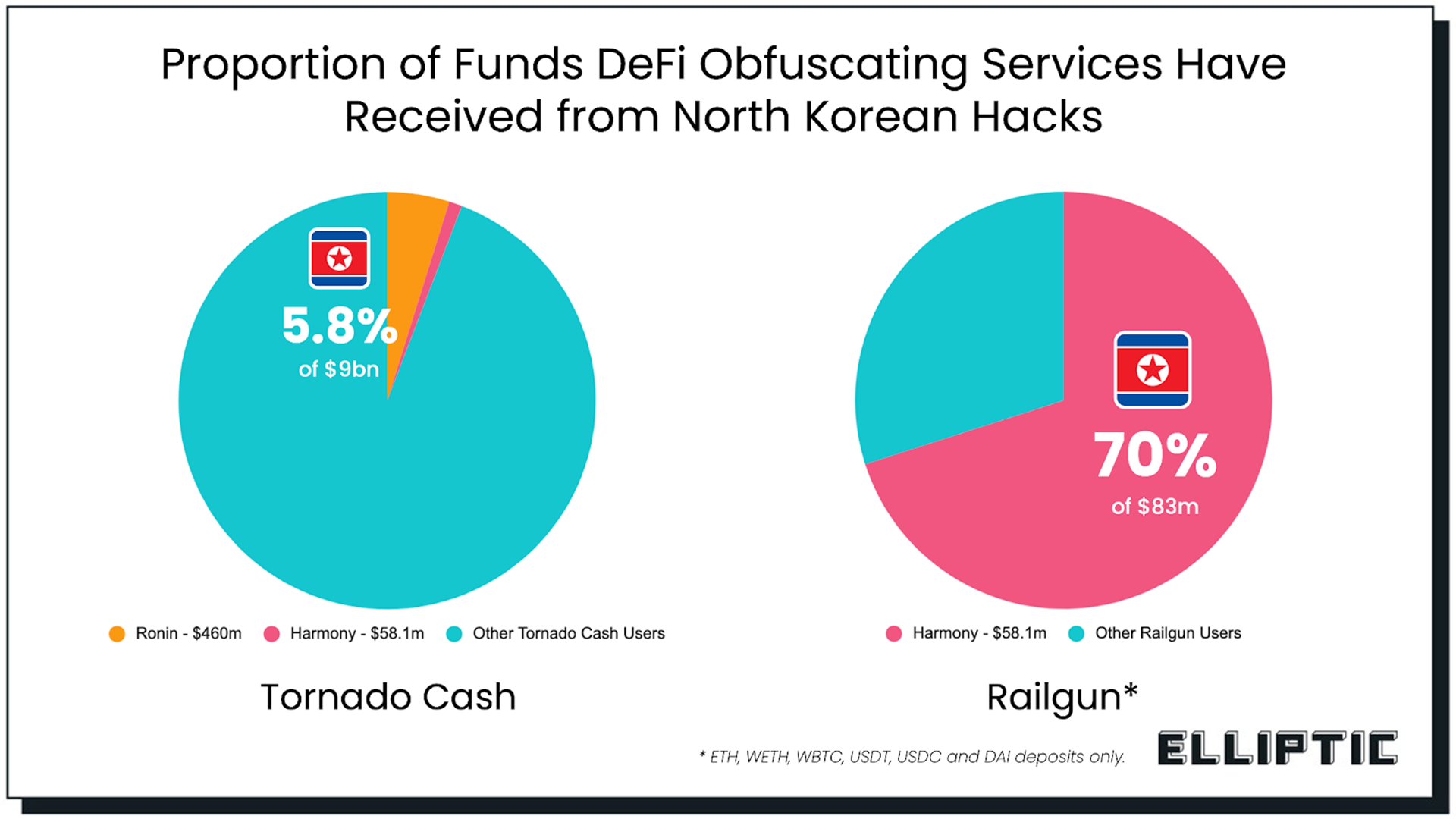

被盗资产包括约 61 枚 BTC、350 枚 ETH、1000 万枚 WEMIX 代币和 22 万 USDT。黑客控制了 GDAC 的热钱包,并迅速将部分资金通过 Tornado Cash 混币器洗白。

-

2025:六年后的同一天,Upbit 再次沦陷

六年前的同一天(11月27日),Upbit 曾损失 342,000 枚 ETH。

历史再次重演。凌晨 4:42,Upbit 的 Solana 热钱包出现异常资金流出,约 540 亿韩元(3680 万美元)的资产被转移至未知地址。

2019 年 Upbit 事件之后,2020 年韩国正式实施《特定金融信息法》(特金法),要求所有交易所取得 ISMS(信息安全管理体系)认证并在银行开设实名账户。大量无法达标的小型交易所被迫退出市场,行业格局从「百所混战」收缩为少数几家巨头主导。Upbit 凭借 Kakao 系的资源背书和认证的通过,市场份额一度超过 80%。

但六年的合规建设,并没有让 Upbit 逃过这一劫。

截至发稿,Upbit 已宣布将用自有资产全额赔付用户损失,但关于攻击者身份和具体攻击路径,官方尚未公布详细信息。

泡菜溢价 、国家级黑客与核武器

韩国交易所频频被盗并非单纯的技术无能,而是地缘政治的悲剧投影。

在一个高度中心化、流动性溢价极高且地理位置特殊的市场,韩国交易所实际上是在用一家商业公司的安防预算,去对抗一个拥有核威慑诉求的国家级黑客部队。

这支部队有个名字:Lazarus Group。

Lazarus 隶属于朝鲜侦察总局(RGB),是平壤最精锐的网络战力量之一。

在转向加密货币之前,他们已经在传统金融领域证明了自己的实力。

2014年攻破索尼影业,2016年从孟加拉国央行盗走8100万美元,2017年策划了波及150个国家的WannaCry勒索病毒。

2017年起,Lazarus 将目标转向加密货币领域。原因很简单:

相比传统银行,加密货币交易所监管更松、安全标准参差不齐,而且一旦得手,资金可以通过链上转移迅速跨境,绕开国际制裁体系。

而韩国,恰好是最理想的猎场。

第一,韩国是地缘对抗的天然目标。对朝鲜而言,攻击韩国企业不仅能获取资金,还能在「敌国」制造混乱,一举两得。

第二,泡菜溢价背后是肥美的资金池。韩国散户对加密货币的狂热举世闻名,而溢价的本质是供不应求,大量韩元涌入,追逐有限的加密资产。

这意味着韩国交易所的热钱包里,长期躺着远超其他市场的流动性。对黑客来说,这就是一座金矿。

第三,语言有优势。Lazarus 的攻击并非只靠技术暴力破解。他们擅长社会工程学,比如伪造招聘信息、发送钓鱼邮件、冒充客服套取验证码。

朝韩同文同种,语言障碍为零,这让针对韩国员工和用户的定向钓鱼攻击成功率大幅提升。

被盗的钱去哪了?这可能才是故事最有看点的部分。

根据联合国报告和多家区块链分析公司的追踪,Lazarus 窃取的加密货币最终流向了朝鲜的核武器和弹道导弹计划。

此前,路透社援引一份联合国机密报告称,朝鲜使用被盗的加密货币资金来帮助资助其导弹开发计划。

2023年5月,白宫副国家安全顾问 Anne Neuberger 公开表示,朝鲜导弹计划约50%的资金来自网络攻击和加密货币盗窃;这一比例相比她2022年7月给出的「约三分之一」进一步上升。

换句话说,每一次韩国交易所被盗,都可能在间接为三八线对面的核弹头添砖加瓦。

同时,洗钱路径已经相当成熟:被盗资产先通过「剥离链」技术拆分成无数小额交易,再经由混币器(如 Tornado Cash、Sinbad)混淆来源,然后通过朝鲜自建的交易所以折扣价兑换成比特币,最后通过中俄的地下渠道兑换成法币。

2019年 Upbit 被盗的34.2万枚 ETH,韩国警方正式公布调查结果显示: 57%在疑似朝鲜运营的三家交易所以低于市场价2.5%的价格兑换成比特币,剩余43%通过13个国家的51家交易所洗白。整个过程历时数年,至今绝大部分资金仍未追回。

这或许是韩国交易所面临的根本困境:

一边是 Lazarus,一支拥有国家资源支持、可以24小时轮班作业、不计成本投入的黑客部队;另一边是 Upbit、Bithumb 这样的商业公司。

即便是通过审查的头部交易所,在面对国家级高持续性威胁攻击时,依然力不从心。

不只是韩国的问题

八年、十余起攻击、约2亿美元损失,如果只把这当作韩国加密行业的本地新闻,就错过了更大的图景。

韩国交易所的遭遇,是加密行业与国家级对手博弈的预演。

朝鲜是最显眼的玩家,但不是唯一的玩家。俄罗斯某些高威胁攻击组织被指与多起DeFi攻击存在关联,伊朗黑客曾针对以色列加密公司发动攻击,朝鲜自己也早已把战场从韩国扩展到全球,比如2025年Bybit的15亿美元、2022年Ronin的6.25亿美元,受害者遍布各大洲。

加密行业有一个结构性矛盾,即一切必须经过中心化的入口。

无论链本身多么安全,用户的资产终究要通过交易所、跨链桥、热钱包这些「咽喉要道」流动。

这些节点集中了海量资金,却由预算有限的商业公司运营;对国家级黑客而言,这是效率极高的狩猎场。

攻防双方的资源从根本上不对等,Lazarus 可以失败一百次,交易所只能失败一次。

泡菜溢价还会继续吸引全球套利者和本土散户,Lazarus不会因为被曝光而停手,韩国交易所与国家级黑客的攻防战远未结束。

只是希望下一次被盗的,不是你自己的钱。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。