Facing the inevitable long-term monetary inflation, Bitcoin and gold are the only two antidotes. Don't choose; have both.

Organized & Compiled by: Deep Tide TechFlow

Guest: Michael Howell, Global Liquidity Expert & Proposer of the Concept of "Global Liquidity"

Host: Ryan Sean Adams

Podcast Source: Bankless

Original Title: The Real Crypto Cycle: What Happens When Global Liquidity Peaks

Broadcast Date: November 24, 2025

About the Guest: Who is Michael Howell?

Michael Howell is a recognized authority on "Global Liquidity" in the global financial community and currently serves as the Managing Director of CrossBorder Capital. He has over 30 years of experience in financial markets, with core insights stemming from his role as Head of Research at the legendary Wall Street investment bank Salomon Brothers in the 1980s.

There, he did not blindly follow traditional economic textbooks but instead, by overlooking a vast trading floor, realized the ultimate truth of the market: The rise and fall of asset prices do not depend on economic fundamentals but on the flow of funds.

This discovery led him to establish the "Global Liquidity Index (GLI)," which covers 90 countries worldwide and has become the most robust indicator for monitoring central bank liquidity, debt refinancing, and capital flows in the market.

For investors wanting to understand "where the money comes from and where it goes," Howell's analysis is a must-read macroeconomic bible.

Key Points Summary

Global liquidity expert Michael Howell has over 30 years of experience. He served as the Head of Research at Salomon Bros and proposed the concept of "Global Liquidity."

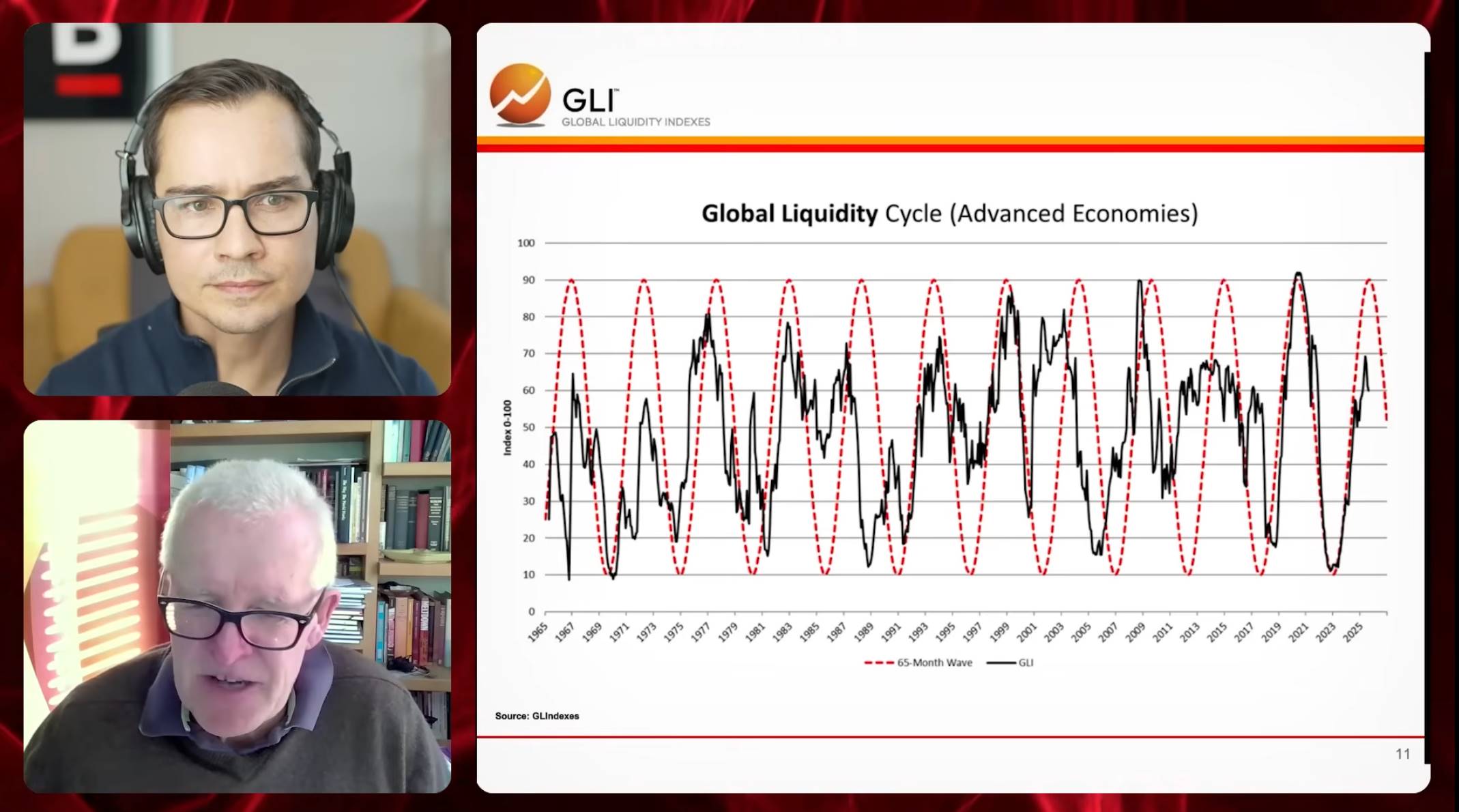

In this podcast, he delves into a core factor driving asset price fluctuations: a 65-month global liquidity and debt refinancing cycle. This cycle is a key driver of market booms and busts and has triggered the recent "everything bubble."

In the interview, he analyzes the upcoming peak in debt maturities, the escalating repo market stress, and the policy shift from Federal Reserve quantitative easing (QE) to "Treasury QE." He also discusses the competition between the U.S.-led dollar stablecoin system and China's gold-backed capital strategy.

Additionally, he examines the potential impacts of these trends on Bitcoin, gold, and stocks, and shares advice on how to optimize investment strategies as the current economic cycle enters a turning point.

Highlights of Insights

- On the Truth of the Financial System: We Are in a "Debt Refinancing" World

Liquidity Over Fundamentals: Capital markets no longer play the traditional role of "financing investments" but have evolved into a system centered on debt refinancing. About 70%-80% of transactions are for rolling over debt rather than financing new projects.

65-Month Cycle: Global liquidity follows a cycle of approximately 65 months, which closely aligns with the average maturity of global debt (about 64 months). The current cycle is in a declining phase, which is the underlying logic for the recent market weakness.

Repo Market Warning: Observing the dynamics of the repo market (Repo Market) over the next 3-6 days can better predict crises than looking at GDP growth. The current widening of repo spreads is a signal of systemic stress.

- On Currency Wars: U.S. Stablecoins vs. Chinese Gold

Division of the Global Currency System: The world is splitting into two camps: one based on U.S. Treasuries + stablecoins forming a digital dollar system; the other is the monetary discipline system being constructed by China, backed by gold.

China's Gold Strategy: The Chinese central bank's large-scale gold purchases and tolerance for rising gold prices are essentially hedging against risks in the dollar system and attempting to establish a new monetary trust mechanism.

The Game of Technology and Resources: This is a capital cold war between U.S. technology (crypto/stablecoins) and Chinese hard assets (gold/industrial capacity).

- On Bitcoin and Gold: Not Either/Or, But Essentials

Best Hedge Combination: In the face of inevitable long-term monetary inflation (an average annual debt growth of 8%), Bitcoin and gold are the only two antidotes. Don't choose; have both.

Interesting Correlation: Bitcoin combines the beta (risk preference) of "Nasdaq tech stocks" and the alpha (currency hedge) of "gold." The two are negatively correlated in the short term (substitution effect) but positively correlated in the long term (jointly combating fiat currency devaluation).

Valuation Logic: About 40%-45% of Bitcoin's driving force comes from global liquidity, 25% from its gold-like properties, and 25% from risk preference.

- Investment Timing and Strategy

Current Opportunity: The market is gradually entering a soft phase (repo stress, liquidity withdrawal), which is precisely an excellent window for allocating Bitcoin and gold, rather than a moment of panic.

Long-Term Trend: Regardless of short-term fluctuations, policymakers have no choice but to print money to address debt. AI may bring technological changes, but it cannot alter the cyclical adjustments in valuation or prevent the long-term fate of currency devaluation.

Global Liquidity: The Theory of Everything?

Ryan: Welcome, Michael Howell. Thank you for being here; it's an honor to speak with you. Today, we hope to explore market issues from the perspective of global liquidity.

You have mentioned that global liquidity is a key variable driving cycles, crises, and changes in asset prices, especially many dynamics in the cryptocurrency space. So, could you start from the basics and share your views? Can global liquidity really be seen as a kind of "theory of everything"?

Michael:

I wouldn't say it's an absolute "theory of everything," but it is indeed very close. I think the important question is, why is global liquidity so critical? Why is the flow of funds a key factor in understanding today's asset prices?

My early insights came from my work at the American investment bank Salomon Brothers. This company was a significant player in the international bond market, with strong trading capabilities and extensive market influence. Salomon was known not only for its research capabilities but also for having a large trading floor. One of the design concepts of this floor was to allow people to visually see the flow of funds between different trading desks. I worked in the research department's office, which overlooked the London trading floor, a vast space. This was happening from the late 1980s to the early 1990s.

By observing the trading floor, I realized that the flow of funds is real-time and dynamic. Salomon's philosophy was that there are no irrelevant events in financial markets; if one trading desk is shouting "buy," there may be another desk at the other end shouting "sell." This flow of funds occurs not only within one trading floor but can extend globally. As Salomon was an international fixed-income broker, it could track these cross-border flows of funds almost in real-time. This observational experience made me aware of the profound impact of fund flows on the market.

Henry Kaufman was the head of research at Salomon at the time, and he published an annual report called "Financial Market Outlook." This report detailed the inflows and outflows of funds in U.S. financial institutions and securities markets. This analytical approach was starkly different from traditional textbook views. Textbooks typically emphasize predicting market trends through mathematical models and yield comparisons, but in reality, changes in asset prices are driven more by supply and demand dynamics, with fund flows being the core variable. This understanding became the foundation for our subsequent research work.

Today, our team focuses on tracking cross-border fund flows and has developed the Global Liquidity Index (GLI). The GLI is a comprehensive indicator used to measure fund flows globally. We have been working in this field for nearly thirty years and are very familiar with the data. The GLI covers 90 countries and aims to be an authoritative source of global liquidity information.

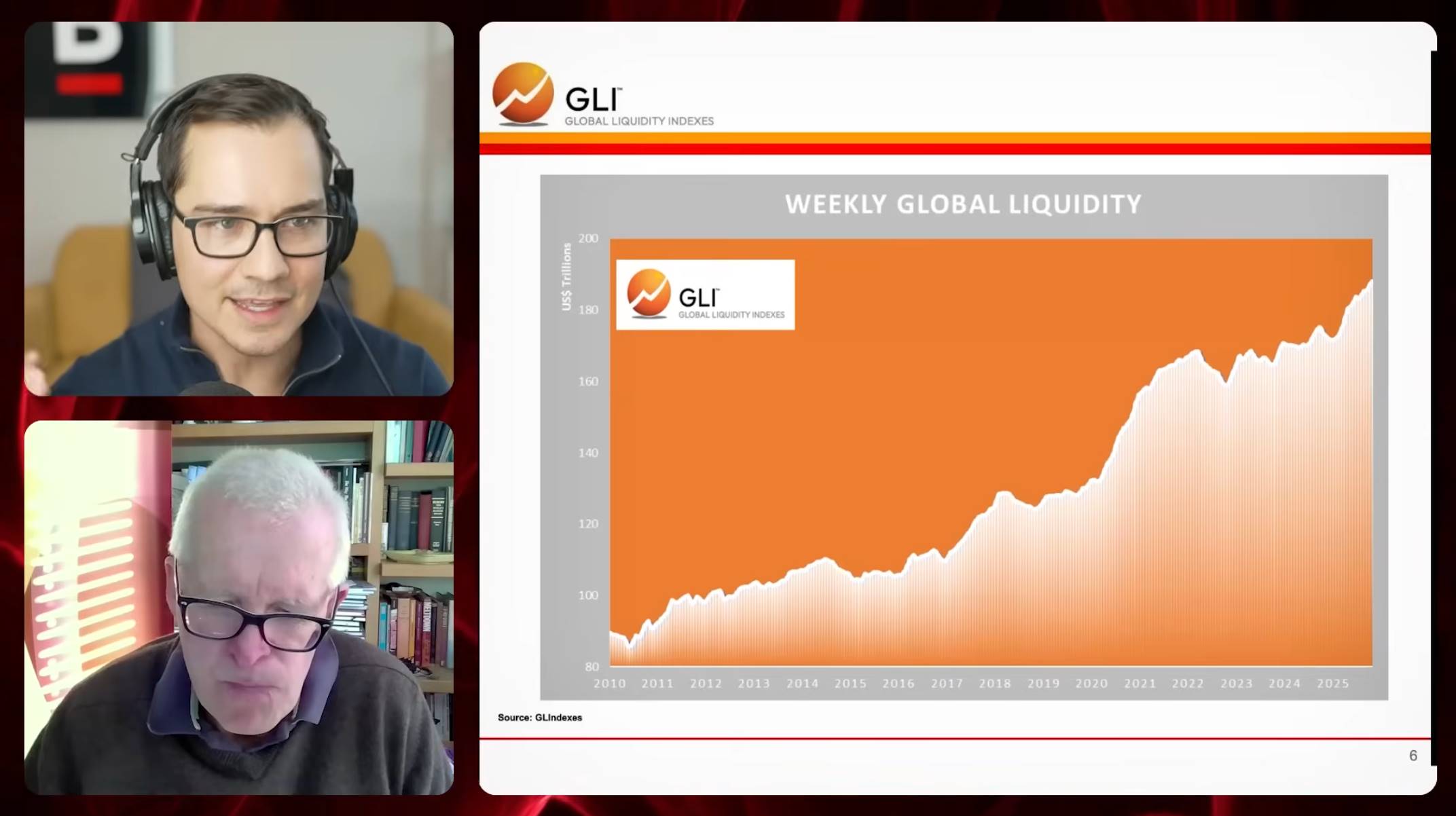

Ryan: The Global Liquidity Index (GLI) tracks global liquidity on a weekly basis, showing changes from 2010 to the present. For those who cannot see the chart, global weekly liquidity was about $100 trillion in 2010, and now it is close to $200 trillion, nearly doubling. So, what does this chart tell us? What does global liquidity specifically refer to? Where does it come from? What can we see from it?

Michael:

Global liquidity refers to the flow of funds in financial markets; it is not equivalent to traditional money supply measures (like M3 or M2). Our definition starts from the boundaries of traditional money supply, focusing on funds in financial markets rather than in the real economy. For example, funds held in bank deposit accounts fall under M2, but these funds are part of the peripheral financial system. What we focus on is the core part, namely the flow of funds in the repo market, shadow banking, and international securities markets. These fund flows are the key factors driving changes in asset prices, which is why we pay close attention to them.

The chart shows the changes in global liquidity levels, measured in U.S. dollars. This data comes from approximately 90 countries, with China, the United States, the Eurozone, and Japan being the main components, while data from smaller countries has a relatively minor impact on the overall picture. Through this data, we can observe the changes in liquidity cycles. For instance, we use the "Global Liquidity Cycle" to measure changes in liquidity momentum. This cycle is quantified by the Z-score of liquidity growth rates, where 50 is the long-term trend value, and the data fluctuates around this trend value, reflecting momentum changes within the cycle.

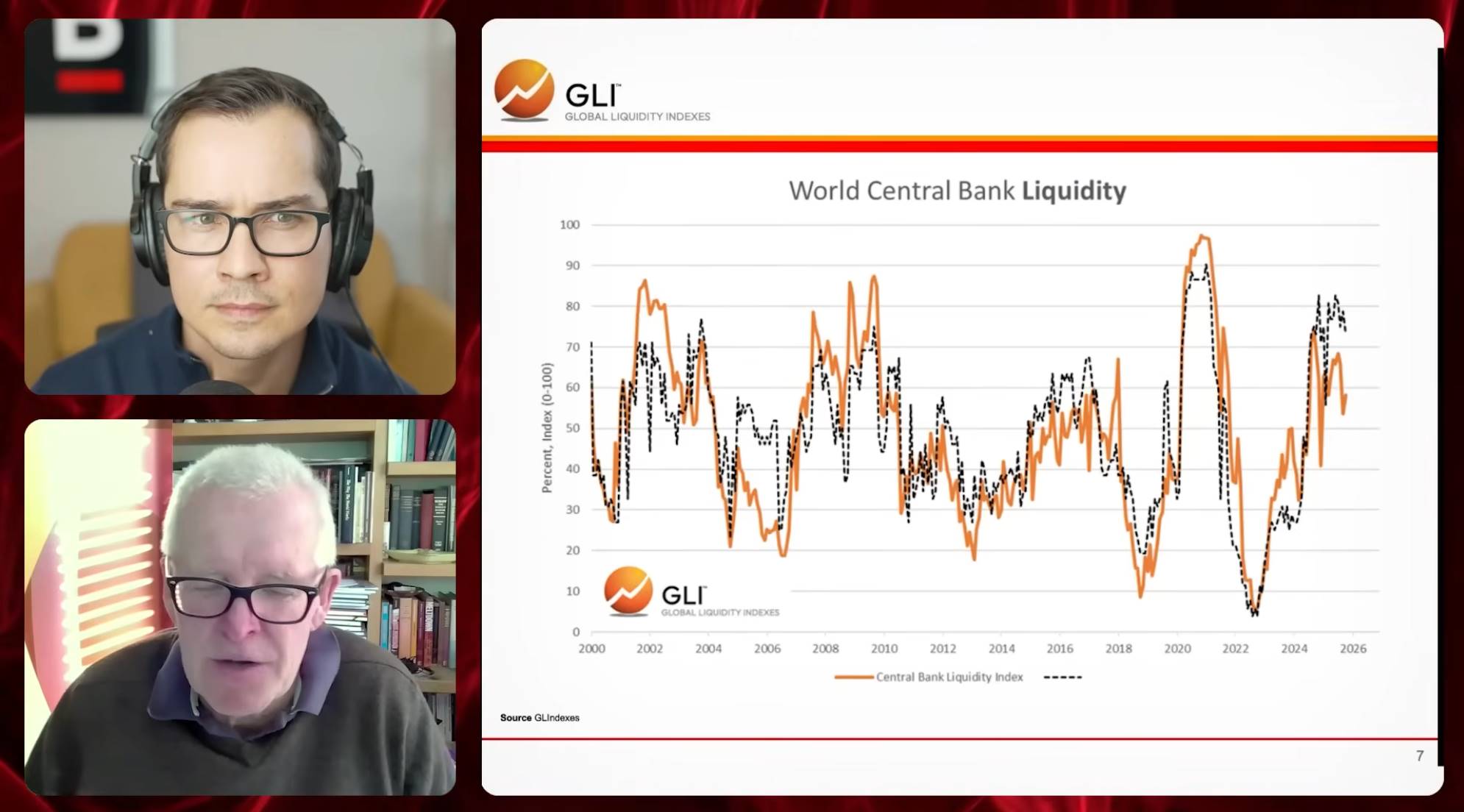

This data can be traced back to the mid-1960s, and our database has been built since that time, with real-time updates starting in the late 1980s. The black line in the chart represents the current momentum indicator, while the red dashed line is a sine wave model we added in 2000 to illustrate a stable 65-month cycle.

Regarding this cycle, we can explore it from two aspects. First is its robustness. Recently, institutions studying cycles have requested relevant data from us, and through in-depth analysis, they found that this 65-month cycle aligns perfectly with their research findings. This consistency indicates that the cycle has strong reliability and provides confidence for experts in the field of cycle research. Secondly, why is it 65 months instead of 50 or 100 months? We believe that this cycle actually reflects the debt refinancing patterns in the global economy. The current debt capital markets focus more on rolling over existing debt rather than raising new funds for investment projects.

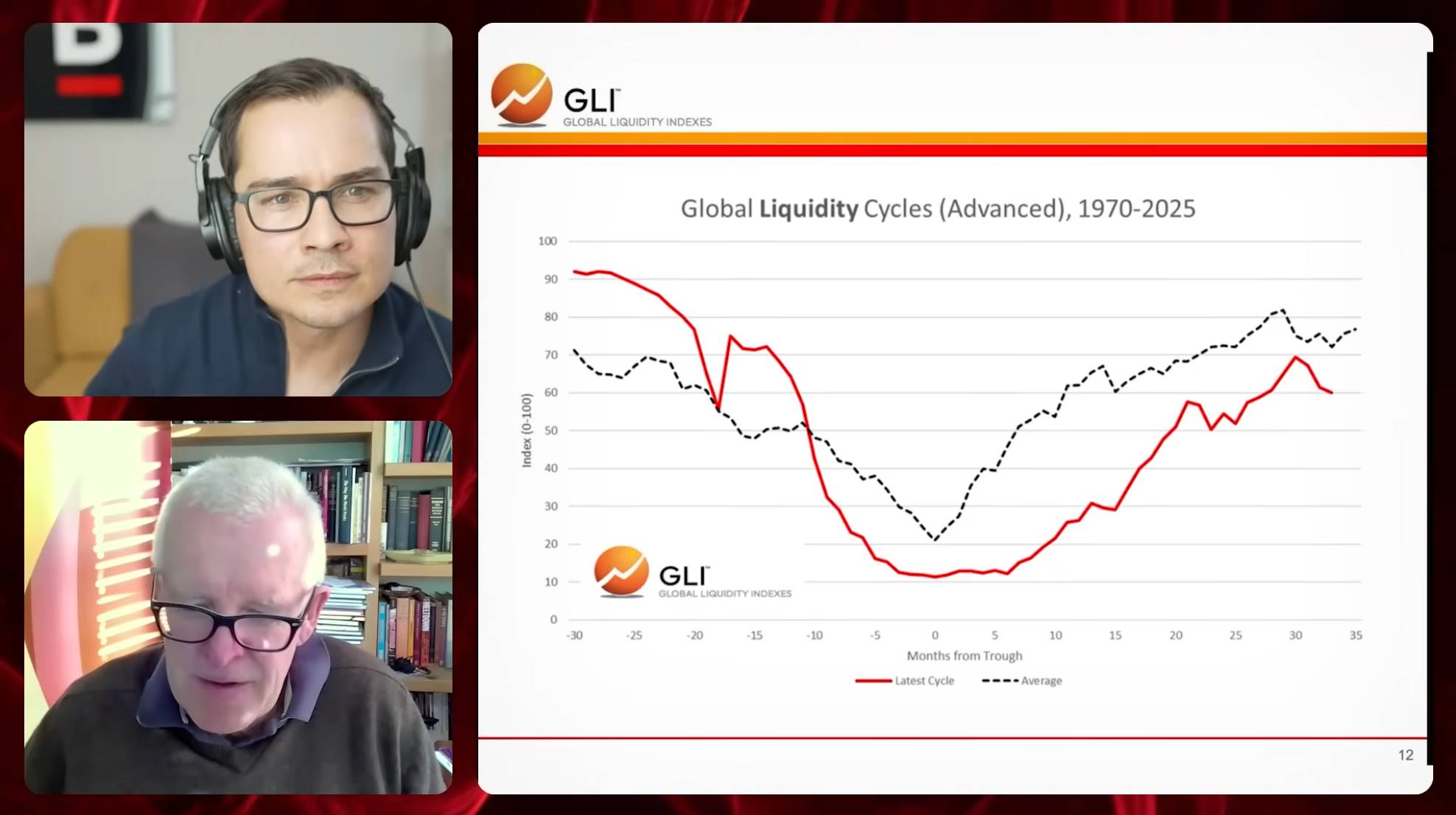

This cycle closely aligns with the average maturity of global debt. Data shows that the average maturity of debt in the global economy is about 65 months (approximately 64 months). Therefore, this cycle may be a result of the system's inherent operations. According to the chart, this debt refinancing cycle bottomed out in October 2022 and is expected to peak by the end of 2025. The current trend indicates that the cycle is in a declining phase.

Of course, we cannot fully determine future trends, such as whether the cycle will reverse and rise again. However, given the current conditions, the likelihood of tightening liquidity is high. It is worth noting that the flow of funds between the real economy and financial markets has a reciprocal relationship. If the real economy begins to recover and gain momentum, funds may flow out of the financial markets, putting pressure on asset prices. **Strong global liquidity growth typically requires two conditions: first, that *central banks* continuously inject funds; second, that real economic growth is relatively weak. However, currently, neither of these conditions is met.**

Additionally, we can observe the trends in global central bank liquidity through another chart. This chart presents the momentum of central bank actions in index form, with the orange line representing a weighted composite indicator, where the U.S. Federal Reserve plays a dominant role in this analysis. The black dashed line shows the proportion of central banks globally that are easing or tightening policies. Currently, about 70% of central banks are still adopting easing policies, but this proportion is declining, and the trend of inflection is evident. This information helps us understand the current position of the cycle and its potential development direction.

Will global liquidity always rise?

Ryan: I want to specifically discuss the Global Liquidity Index. Why does it always show an upward trend? While we know that cyclical fluctuations are embedded within it, it seems that global liquidity is in a long-term super cycle. What are the main driving factors behind this sustained increase? Is it always going to be this way, or is there a possibility of a reversal at some point?

Michael:

That's a very good question. I think this can be traced back to the importance of liquidity in the market. In a debt-dominated world, the primary use of liquidity is to help roll over or refinance existing debt to address maturity pressures. Historical data shows that in major transactions in financial markets, about 70% to 80% are debt refinancing transactions rather than raising new capital. This is in stark contrast to the situation described in traditional economic textbooks, where the primary function of capital markets was to raise funds for investment projects, but this model has fundamentally changed.

For example, while many investments in the AI sector are exceptions, the funding for these investments typically comes from the cash flow or fiscal reserves of large tech companies rather than being raised through capital markets. If we look at China, the world's largest capital investor, its funding primarily comes from state sponsorship rather than capital markets. Therefore, capital markets no longer play the role described in traditional textbooks, and many indicators and theories based on old models are no longer applicable. We need to shift to a new perspective—a financial system centered on debt refinancing.

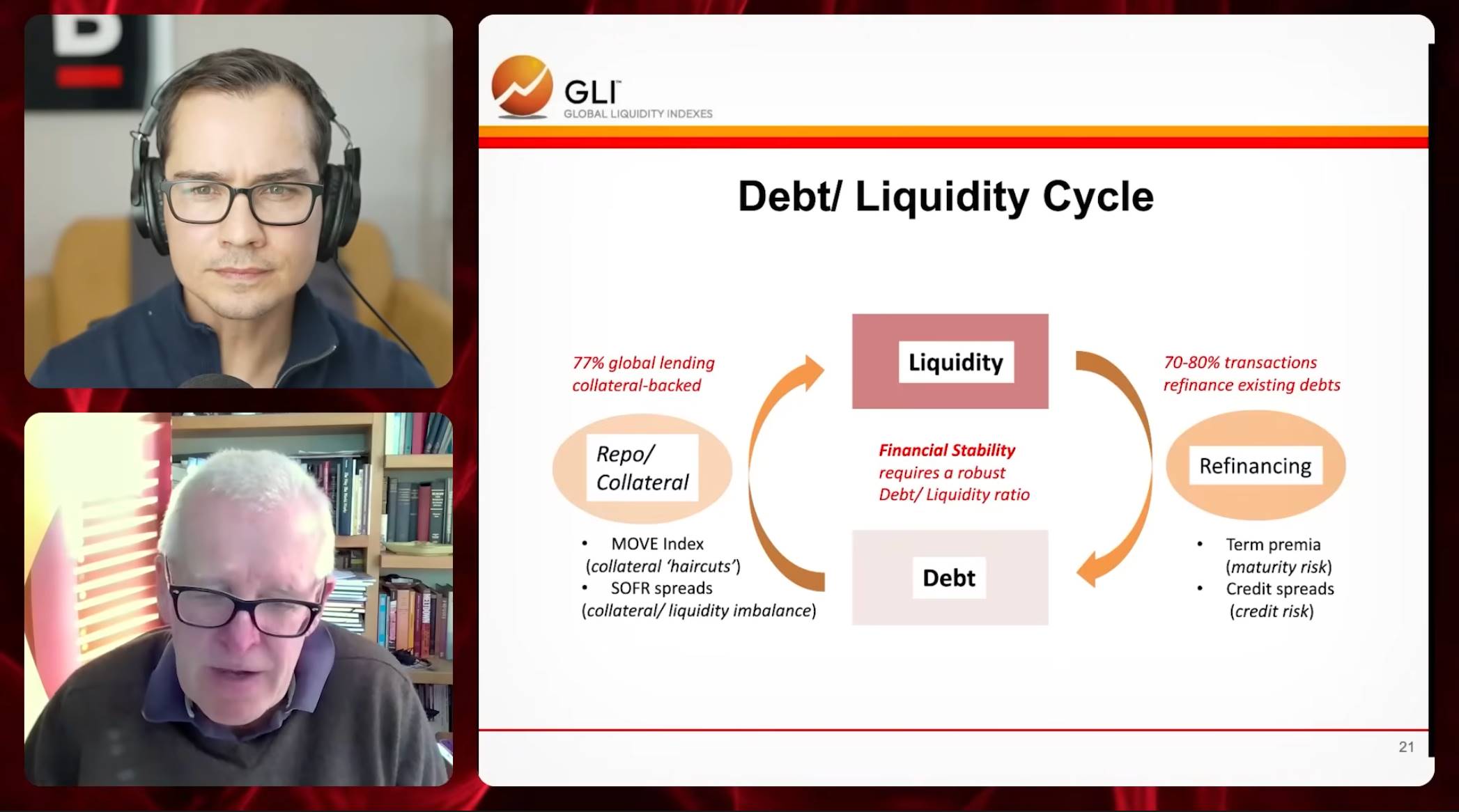

Next, I can further illustrate this point with this slide, which is called the "Debt Liquidity Cycle." It reveals the core operational logic of the financial system and explains the evolution of the financial system since the 2008 global financial crisis. At the core of the chart is the so-called "debt liquidity link," which can be seen as the core mechanism of the modern financial system. As I have repeatedly emphasized, the primary function of the modern financial system is to support debt refinancing.

However, there is a paradox here: debt requires liquidity to roll over, and liquidity itself also depends on the existence of debt. This interdependent relationship forms the foundation of the current financial system.

According to World Bank data, about 77% of loans globally are secured by collateral. These collaterals include both real estate mortgages and many financial transactions, such as the foundational trades of hedge funds, which often use government bonds as collateral to support borrowing. Therefore, we need to deeply understand the role of collateral in the financial system.

In other words, debt needs liquidity, and liquidity also needs debt. An interesting phenomenon is that old debt actually supports new liquidity, and this interdependence forms the core operational mechanism of the modern financial system.

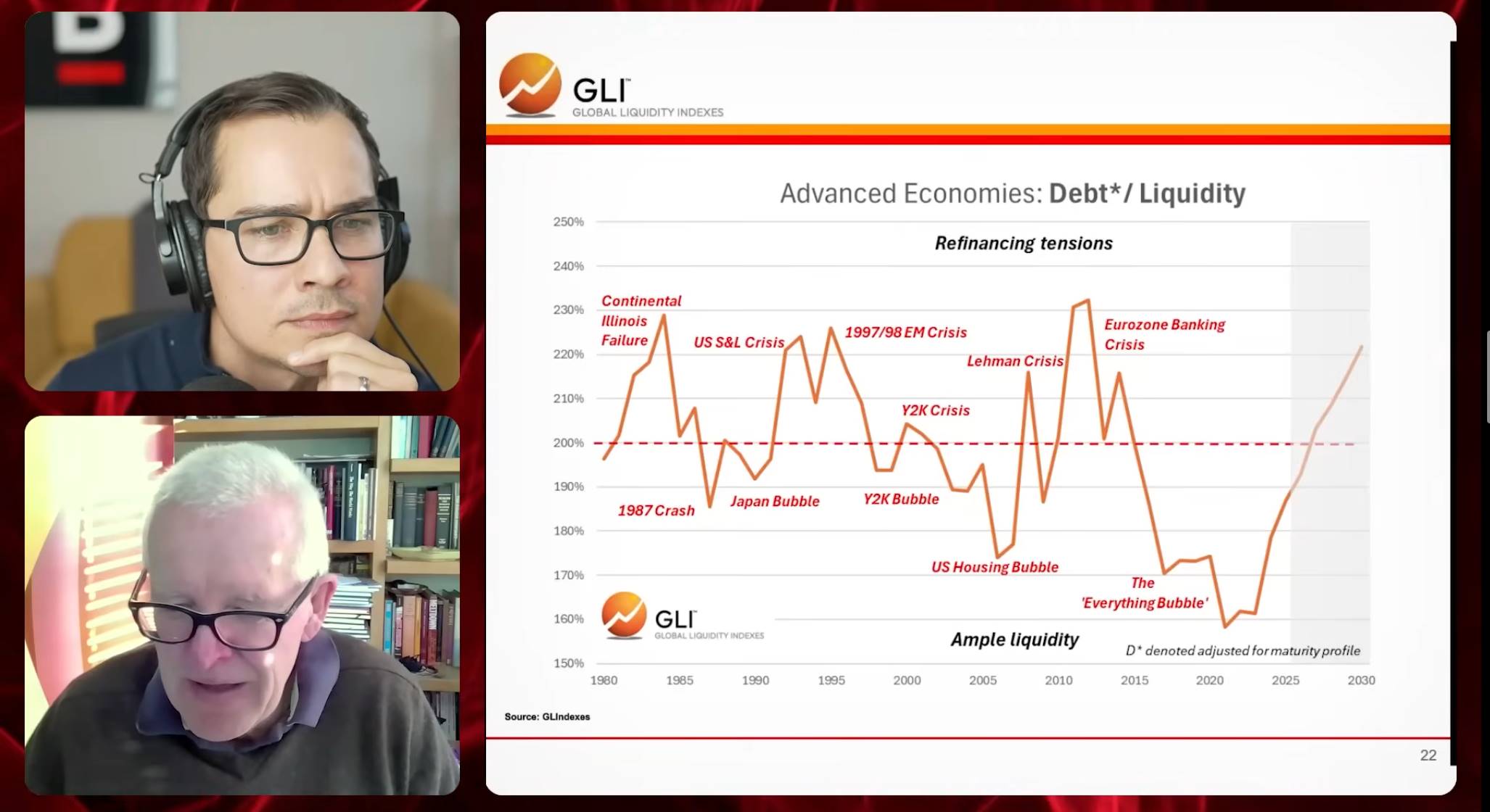

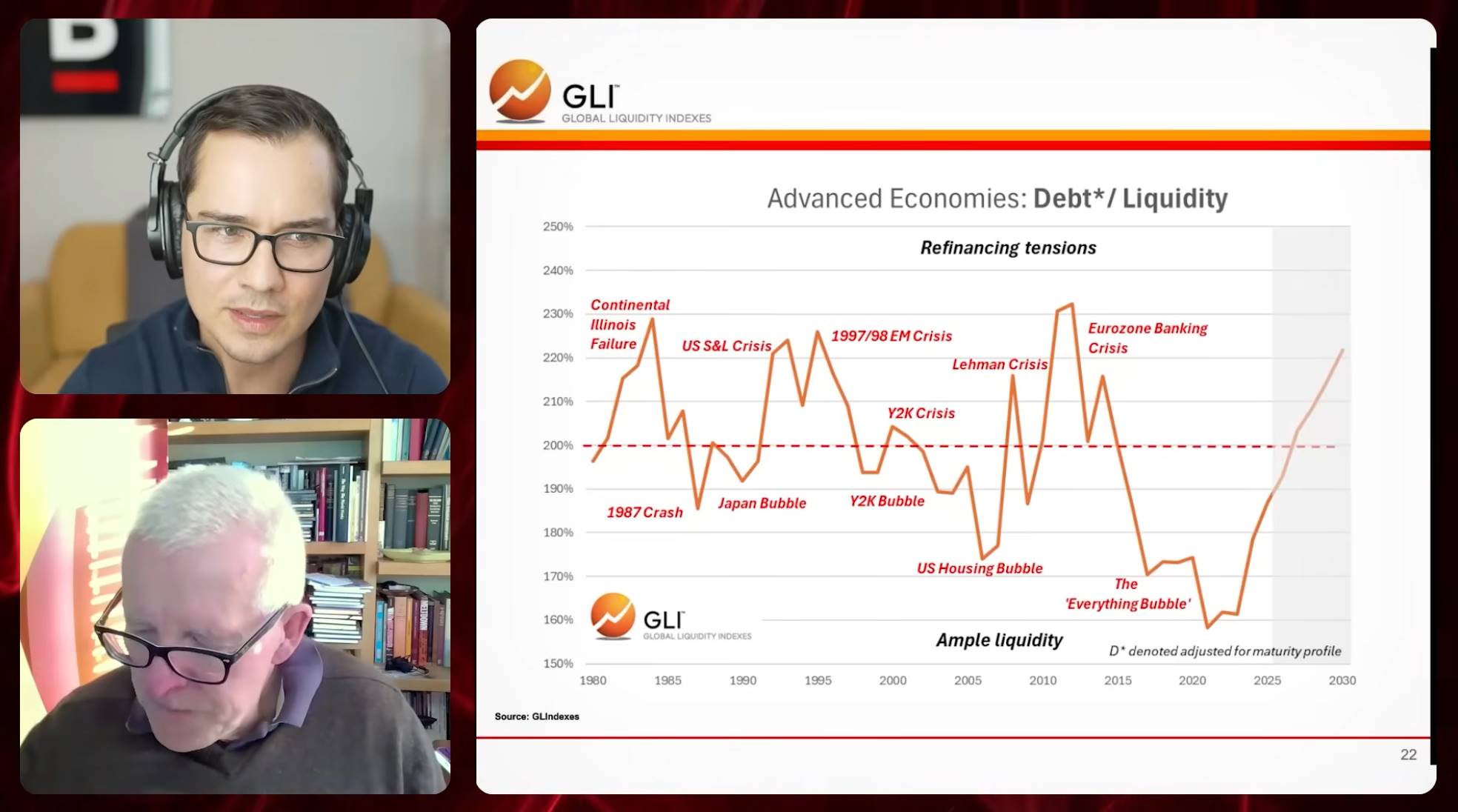

To ensure the stability of the financial system, we need to maintain a healthy debt liquidity ratio. Currently, the total debt stock in developed economies (including public and private debt) is about $300 trillion. The so-called debt liquidity ratio refers to the ratio of an economy's liquidity to its debt stock, with an average value typically around 2 times. This ratio has a mean-reverting characteristic, meaning that when the ratio deviates from its long-term average level, it usually gradually returns to the mean. Compared to the traditional debt-to-GDP ratio, the debt liquidity ratio can more accurately reflect an economy's ability to refinance its debt.

When this ratio is too high, it indicates that the relationship between debt levels and liquidity is too strained, which may lead to financing difficulties or refinancing pressures, potentially triggering a financial crisis. Conversely, when liquidity far exceeds debt, it may give rise to asset bubbles. Looking back, we have experienced a phase known as the "everything bubble," characterized by abundant liquidity and relatively low debt pressure. Now, we are gradually transitioning out of this phase.

The emergence of this phenomenon is closely related to policymakers' responses. After each economic crisis, policymakers typically inject a large amount of liquidity into the market through quantitative easing (QE) to promote the growth of liquidity within the system. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, global interest rates were lowered to near-zero levels. Low interest rates not only encouraged the generation of more debt but also extended the average maturity of debt. During this period, many debts were refinanced at low interest rates, leading to the so-called "debt maturity wall" phenomenon, where a large amount of debt will mature in the coming years.

This phenomenon may pose challenges to the market but may not directly trigger a crisis. In recent years, zero interest rate policies have led to many debts being extended to mature in the coming years, resulting in a decrease in current debt increments. However, this delayed effect intensifies the pressure of concentrated debt maturities in the coming years, necessitating large-scale refinancing. This is one of the main challenges we currently face.

Moreover, the relationship between liquidity and asset bubbles is also worth noting. Historical data indicates that surges in liquidity are often closely associated with the formation of asset bubbles. Currently, we are in the concluding phase of the "everything bubble," primarily due to two reasons: first, a large amount of debt will mature in the coming years; second, central banks, especially the Federal Reserve, are gradually reducing the pace of liquidity injections. These factors collectively drive the end of the "everything bubble" phase.

Which stage of the cycle are we in?

Ryan: From this chart, when the debt-to-liquidity ratio is below 200%, we often see the formation of asset bubbles, such as the Japanese bubble, the Y2K bubble, the internet bubble, and the U.S. housing bubble. Currently, we are in the "everything bubble" phase. However, when the ratio exceeds 200%, it typically triggers a financial crisis. From the chart you presented, it seems we are nearing the end of the cycle, especially the tail end of the asset price increase cycle. As liquidity gradually decreases, we are returning to a realm closer to crisis.

Michael:

This chart shows the current cycle (red line) compared to the average cycle since 1970 (dashed line), with the zero axis as the baseline. The bottom zero line represents the trough of the cycle, and you can measure left or right by months, which is also one of the previously mentioned 65-month cycles.

Generally speaking, the range of this cycle is about plus or minus 8 months. If this range is accurate, then we need to be cautious in asset allocation. At the same time, I think it is necessary to distinguish between cycles and trends. One thing we are very clear about is that the trend of monetary inflation that has driven the market over the past decade may continue for the next two to three decades.

The trend of monetary inflation is very evident. This is mainly due to the enormous fiscal burdens faced by economies, including welfare spending and defense expenditures. The only choice for policymakers is to respond by printing money or monetizing debt, which inevitably leads to monetary inflation. Monetary inflation is a long-term issue that we all need to address, but in the short term, what we need to focus on is the tightening conditions in the repo market.

The tightening conditions in the repo market are intensifying, manifested by the continuous widening of the repo spread (the difference between the SOFR rate and the federal funds rate). Theoretically, the SOFR rate, being based on collateral, is usually lower than the federal funds rate, but recently this spread has exceeded the normal range by about 10 basis points, entering the "danger zone." More concerning is that the magnitude and frequency of these rate fluctuations are significantly increasing, indicating heightened pressure in the repo market, which may threaten the stability of the financial system.

This phenomenon is closely related to the Federal Reserve's liquidity policy. Changes in Federal Reserve liquidity are not solely determined by the balance sheet, as some items within it consume liquidity. True changes in liquidity require monitoring by excluding unrelated components. For example, in 2021, the Federal Reserve's liquidity growth rate reached an annualized 80% during the pandemic, but a year later, it quickly dropped to negative 40%, reflecting the impact of monetary tightening policies.

During periods of monetary tightening, the Federal Reserve took measures to combat inflation, leading to shocks in the financial system, such as the Silicon Valley Bank incident and the UK debt crisis. Subsequently, the Federal Reserve adjusted its policy direction, gradually increasing liquidity in 2023, but the overall growth rate remains low. At the beginning of 2025, due to the implementation of the debt ceiling, there was a brief surge in liquidity, but the subsequent replenishment of the Treasury's general account funds withdrew liquidity from the market, exacerbating systemic pressure.

Overall, the Federal Reserve's liquidity is still showing a negative growth trend. Although quantitative tightening (QT) has ended, its impact is limited. It is expected that liquidity may moderately recover in the second half of 2026, but this will depend on the return of quantitative easing (QE). The S&P 500 index typically lags behind changes in Federal Reserve liquidity by about six months; whenever liquidity sharply declines, the market often adjusts accordingly. The current market volatility may reflect this pattern, but the specific outcomes still need to be observed.

Asset Allocation

Ryan: It seems we may be at the tail end of a cycle, with some liquidity in the market being gradually withdrawn. At the same time, there may be some warning signals emerging in the repo market, or at least it needs to be closely monitored. This could mean that this 65-month liquidity cycle is nearing its end, and risk assets may be impacted, potentially approaching a crisis. Please integrate this information to analyze the current state of the cycle and what it means for various assets held by investors.

Michael:

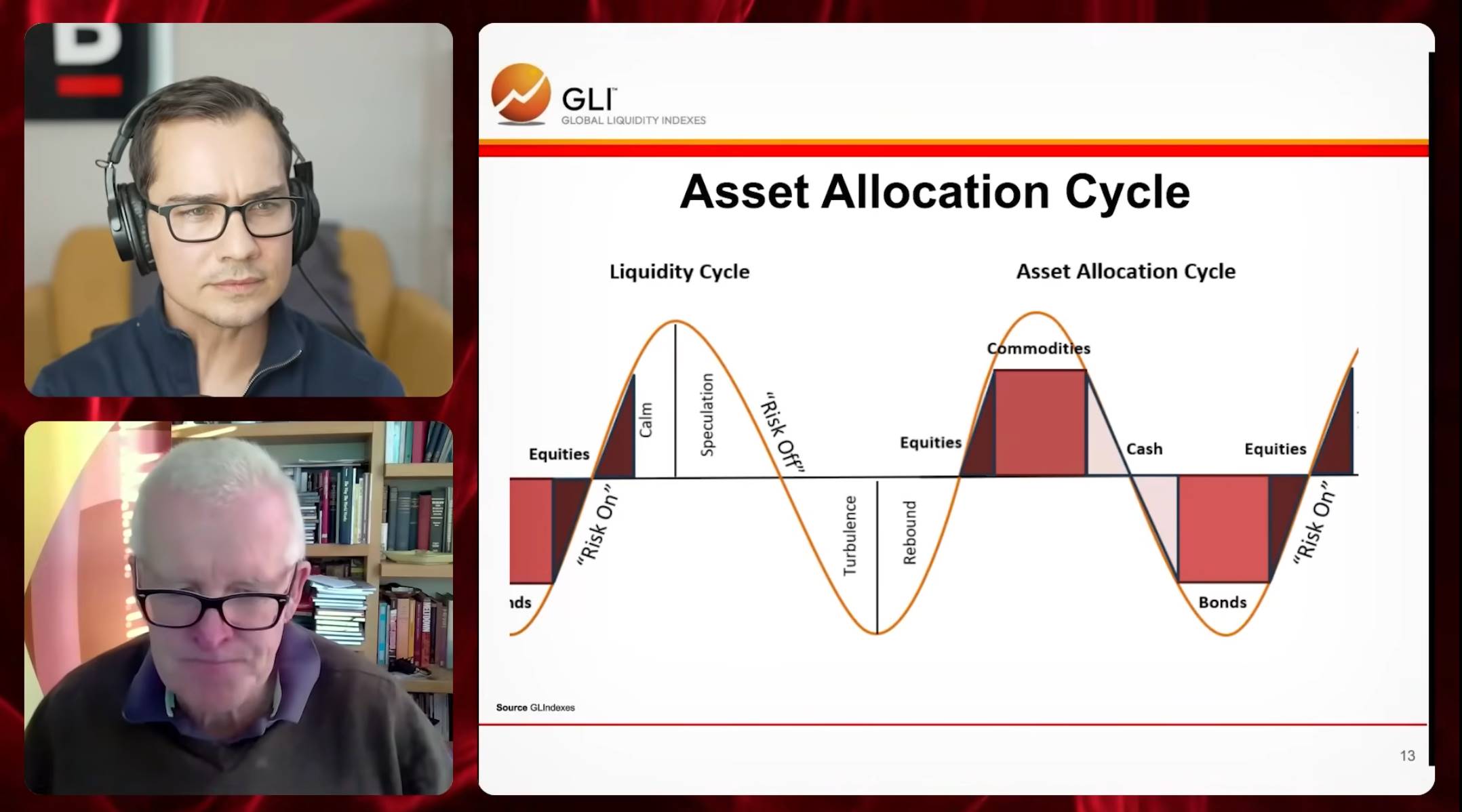

Let me elaborate. This diagram illustrates the relationship between the liquidity cycle and the asset allocation cycle. From the perspective of the liquidity cycle, it can be divided into four stages: calm period, speculative period, turbulent period, and recovery period. Each stage corresponds to different performance characteristics of assets. Although there may be some overlap between these stages, overall, they roughly align with the performance cycles of major asset classes.

While not perfectly aligned, they generally correspond to the performance cycles of asset classes. In the chart, we have labeled the major asset classes: stocks, commodities, cash, and bonds.

Typically, when the cycle is in the recovery and calm periods, risk assets tend to perform well. Particularly in the later stages of the recovery period and the later stages of the calm period, stocks are usually the best-performing asset class. When the cycle reaches its peak, transitioning from the calm period to the speculative period, commodities often perform well. In the declining phase of the cycle, cash usually shows the best absolute returns among asset classes. At the bottom of the cycle, government fixed-income assets, especially long-term bonds, typically perform excellently.

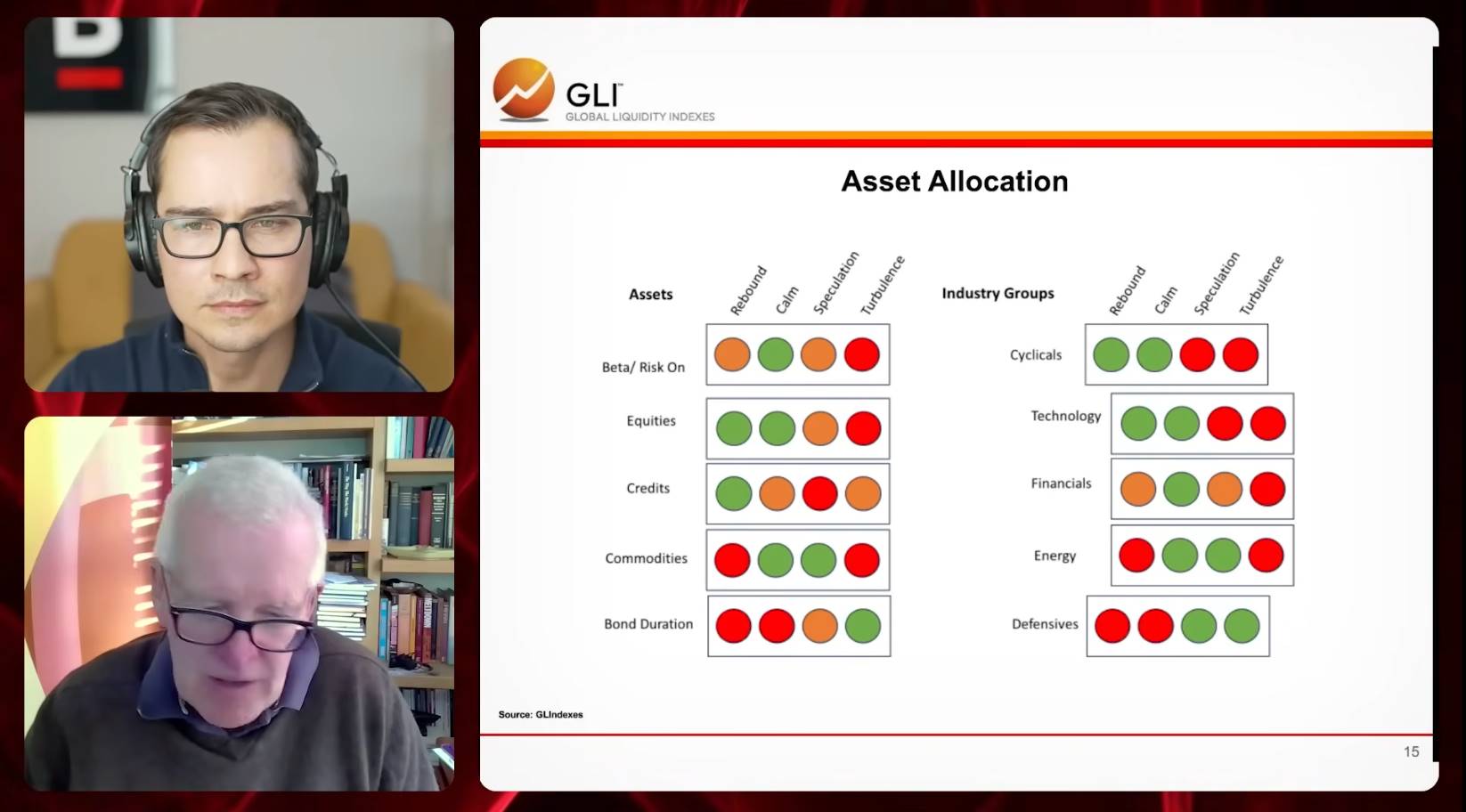

After the phase of poor performance for risk assets ends, the cycle will enter a new phase where risk assets perform well again. We can use a traffic light chart to illustrate this more intuitively.

The left side shows the allocation of major asset classes, while the right side displays the industry allocation within stocks or credit. The traffic light chart uses green, yellow, and red signals to indicate investment strategies. Green indicates active investment, yellow indicates caution, and red signifies stopping. This chart tells us that during the recovery phase, which is the early upward stage of the cycle, while not necessarily adopting a high-risk strategy, it is generally advisable to cautiously increase the allocation to risk assets. Stocks and credit are the best-performing asset classes during this stage, hence the green signal. As we enter the calm period, credit allocation should be gradually reduced, with more focus on the commodity market, making stocks and commodities the best choices for this stage.

In the speculative phase, credit carries higher risks. At this time, investors should allocate more to commodities and physical assets while gradually reducing extreme positions in stocks. During the turbulent phase, government long-term bonds are the most suitable assets for allocation.

Currently, the performance of stocks and commodities is not ideal. If industry yields perform well, credit may gradually recover. From an industry perspective, cyclical stocks perform well during risk appetite phases, while defensive stocks dominate during risk-averse phases. Tech stocks are typically the leaders in the early stages of the cycle and can maintain good performance during the calm period. Financial stocks usually perform outstandingly in the mid-cycle, especially during the calm period. Energy commodities perform strongly during the speculative phase and when the cycle peaks.

Although there has not been a significant economic cycle to reference since the end of the pandemic, the asset allocation cycle and liquidity cycle have been performing normally. This is mainly because government spending dominates in Western economies, leading to less pronounced business cycles. However, the liquidity cycle has shown a typical pattern from the bottom to the current peak. If we observe the performance of asset allocation, a simple glance at the traffic light chart suffices. This traffic light chart is not specifically designed for the current cycle but is applicable to all cycles. We have been using this method for decades, and it has always been effective.

In terms of performance, stocks have outperformed credit, and credit has outperformed bonds. The commodity market is now beginning to recover. Tech stocks have consistently been the market leaders, and financial stocks have performed excellently globally over the past 18 months. Energy commodities, such as gold mining companies, have performed particularly well this year. These signs indicate that this is indeed a typical cycle.

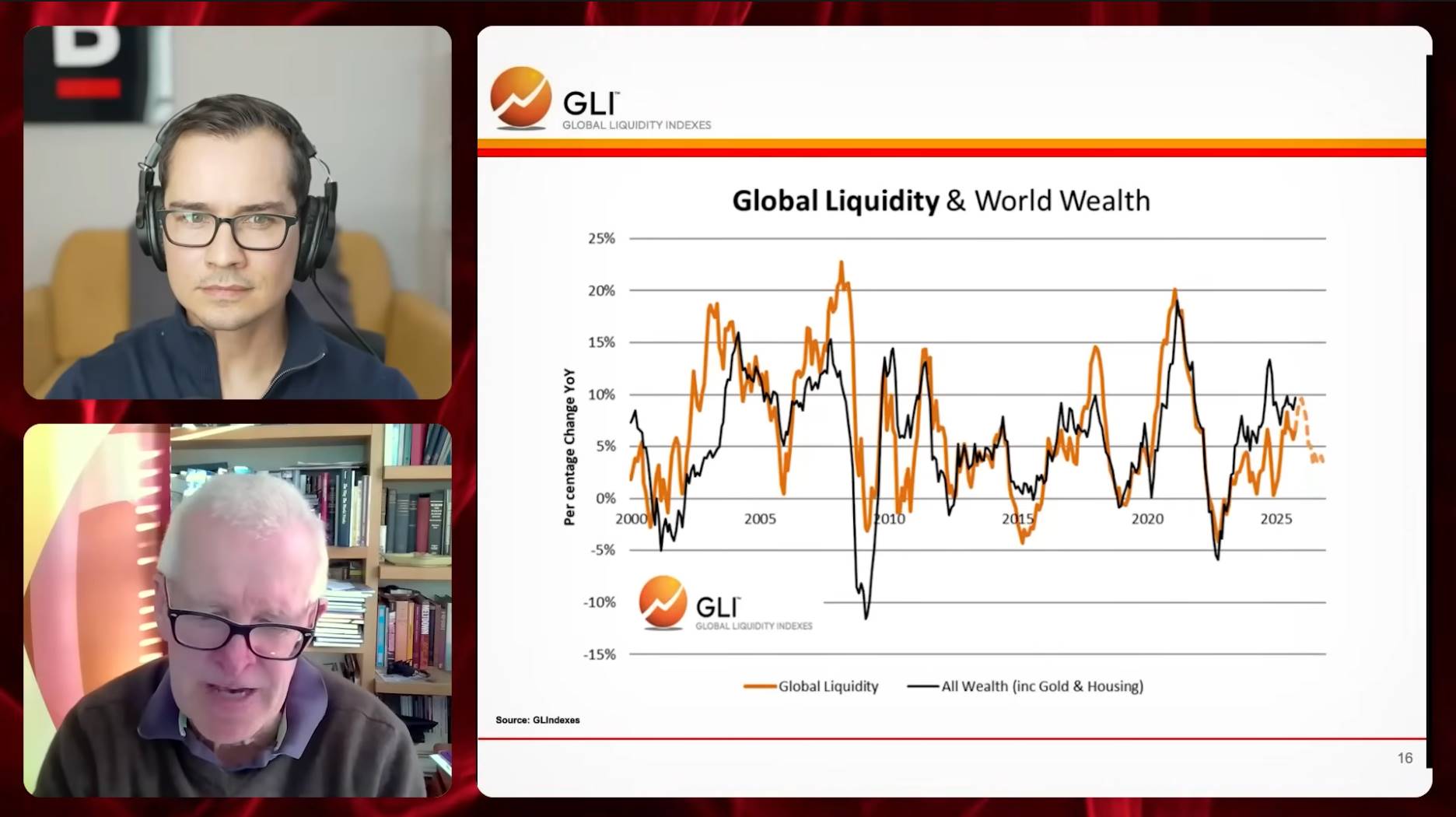

Additionally, we can see a chart that demonstrates the close correlation between global liquidity and global wealth. This chart covers all major asset classes, including stocks, bonds, liquid assets, residential real estate, cryptocurrencies, and precious metals. The annual returns of these assets are compared with the global liquidity growth rate (measured in U.S. dollars), showing a significant correlation between the two.

However, if we trace the data back to before 2000, while there was still some correlation between global liquidity and wealth growth, this connection was not as strong as it is now. Since 2010, the correlation has significantly strengthened. This indicates that liquidity has become one of the important driving factors behind global wealth returns. In other words, the market's performance increasingly relies on liquidity supply rather than traditional economic fundamentals.

This trend is clearly an important dynamic in the current market and has garnered government attention. Treasury Secretary Bessent has taken measures to attempt to end the Federal Reserve's loose monetary policy and to direct more funds through the Treasury into the real economy. The core goal of this policy direction is to mitigate the impact of excess liquidity on the market while reducing the risk of social division. If this issue is not effectively addressed, social inequality may further exacerbate, leading to greater challenges.

Additionally, we have specifically analyzed the performance of cryptocurrencies. As an emerging asset class, the relationship between cryptocurrency price fluctuations and global liquidity is gradually becoming evident.

We used high-frequency data to record weekly changes and observed them using a six-week time window. We found a high correlation between global liquidity and cryptocurrency performance, suggesting that as the global liquidity cycle changes, cryptocurrencies may play an increasingly important role in investment portfolios.

Ryan: Michael, from your analysis, it seems we are between the calm period and the speculative period. What do you think? Are we nearing the end of the speculative period?

Michael:

It depends on the specific economy. For example, the U.S. has clearly entered the speculative period, as evidenced by the data we have, while the European market and some emerging Asian markets are in the later stages of the calm period.

Ryan: **It seems we can consider the current cycle to be between the calm period and the speculative period. We can confirm that we are not in the turbulent phase or the recovery phase. So for these asset classes, such as stocks, *credit*, commodities, *bonds* duration, where does cryptocurrency fit? Is it in the commodity category or the risk asset category?**

Michael:

**Cryptocurrency's performance resembles both *tech stocks* and commodities; it has characteristics of NASDAQ as well as attributes similar to gold. Therefore, cryptocurrency is essentially a combination of the two. In terms of trends, its performance is similar to gold, while in terms of cycles, it aligns more with the cycles of tech stocks.**

If we delve into the driving factors of cryptocurrencies, we primarily focused on Bitcoin, and research indicates that about 40%-45% of Bitcoin's driving factors are related to global liquidity. Of the remaining portion, about 25% is related to gold, and another 25% is related to risk appetite. Risk appetite can be measured through indicators like NASDAQ. If Wall Street suddenly experiences a sell-off due to cautious investors, this could impact Bitcoin's performance. Gold, on the other hand, is less affected by risk appetite. Therefore, Bitcoin is more susceptible to market fluctuations or tech stock volatility than gold.

The relationship between Bitcoin and gold is very interesting; they exhibit a negative correlation in the short term but a positive correlation in the long term. Mathematically, this aligns with an error feedback system. In simple terms, the long-term trends of Bitcoin and gold are consistent, but short-term fluctuations are independent. Bitcoin can run far in the short term but will ultimately revert to the direction of gold. Recent market performances have validated this, as when gold prices rise, Bitcoin may perform poorly or even decline; conversely, when Bitcoin prices rise, gold may remain unchanged or even decline. This short-term negative correlation will ultimately be balanced by the long-term positive correlation, as both serve as hedges against monetary inflation, but may act as substitutes in the short term.

Will the monetary system collapse?

Ryan: Michael, your prediction is that the GLI (Global Liquidity Index) will continue to rise. I have a question: since this data is measured in U.S. dollars, can it be likened to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system? What I mean is that every 70 to 90 years, the monetary system seems to undergo a significant transformation.

If we are indeed entering a new monetary system, will this trend collapse? Or will the foundation of this system disintegrate? Or will it continue to grow? What are your thoughts?

Michael:

That's a very good question. Historically, monetary systems do evolve over time, and I believe we are in a new transformative phase, especially after the U.S. introduced stablecoins. If this form of currency is carefully designed rather than emerging by chance, its impact will be profound, and the reshaping of the global financial system will be significant.

We can understand this through the "debt liquidity ratio." This ratio reflects the relationship between the scale of debt and liquidity, showing a certain stability over the long term across different countries and monetary systems. Since both the numerator and denominator use the same unit, it clearly illustrates the dynamic relationship between debt and liquidity.

However, this stability does not apply in all cases. For some emerging economies, if they have borrowed a large amount of dollar-denominated foreign debt but can only provide liquidity in their local currency, there is a significant risk of debt default. This situation has indeed occurred in history and typically requires international assistance or a restructuring of the monetary system to resolve. However, for developed Western economies, default is almost impossible because the operation of the entire financial system relies on the continuity of existing debt.

As I mentioned earlier, the current financial system is debt-centric, and new liquidity is usually issued against old debt as collateral. Therefore, these old debts cannot default and must be maintained through rollovers or other means; this dynamic mechanism is key to the sustainability of the current system. So, what will the future look like?

Taking Japan and China as examples, we can observe the characteristics of their economic operations through the debt liquidity ratio. In Japan, we saw this ratio peak around 2005 and 2010, reaching as high as 300%. While China's debt liquidity ratio peaked at a lower level, its trajectory is very similar to Japan's. It is important to note that this ratio reflects the debt structure rather than the overall health of the economy.

So how did Japan respond to the high debt liquidity ratio? The answer is through economic stimulus policies. The Bank of Japan massively purchased government debt while printing money, leading to a depreciation of the yen, which in turn reduced this ratio. If we apply this thinking to China, would China choose debt default? The answer is no. China is more likely to respond to current economic pressures by monetizing debt. Although this process may not be completed in one go, current trends indicate that China is heading down a similar path.

We have already seen that China's monetary policy is leading to inflation, and the rise in gold prices is a clear signal. The People's Bank of China significantly increased liquidity injections at the beginning of 2025, which directly drove up the price of gold denominated in renminbi. This indicates that China is indirectly addressing the challenges posed by its monetary policy through the regulation of gold prices.

If you need evidence, you can look at the trend of gold prices. Why have gold prices continued to rise? The reason is that China is purchasing large amounts of gold while supporting this action through money printing. This is a mechanism: by increasing the money supply, China is effectively exerting influence on gold prices.

The liquidity injection data from the People's Bank of China illustrates this well, as there was a significant increase in liquidity injections at the beginning of 2025. Although there has been a recent slowdown, the overall liquidity level remains high. This is not a coincidence; at the same time, the price of gold denominated in renminbi has also performed very strongly. I believe this is one of the reasons why China is driving gold prices, all centered around the core objectives of China's monetary policy.

So why did China choose to take such action now rather than a year or two ago? I believe this is closely related to the threat posed by stablecoins. The emergence of stablecoins has made China realize that the integrity of its monetary system is facing challenges.

Stablecoins, as an innovative tool, provide global investors with a new way to store value, especially in countries with unstable currencies or unfriendly tax policies. For example, in Europe, the European Central Bank has publicly stated that U.S. stablecoins could lead to Europe losing control over its monetary system. For China, this threat is even more severe.

Chinese exporters have actually become highly dollarized, with most of their income denominated in dollars. For these exporters, there are two options: one is to deposit dollars in the Western banking system, but this carries the risk of being seized (as seen in the case of Russia after the Ukraine war); the other is to deposit funds in domestic Chinese banks, but this could also face losses due to policies or other factors. Therefore, rather than choosing between these two risks, it is better to transfer funds into U.S. stablecoins. The anonymity and convenience of stablecoins make them the preferred choice for many investors, as opening a stablecoin account is much easier than a traditional bank account.

From a global perspective, it is not just China and Europe; regions with unstable monetary systems, such as Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, may also begin to adopt stablecoins on a large scale. This could have profound implications for the global monetary system.

Therefore, I believe that the world is splitting into two main monetary systems. On one hand is the dollar-based system, centered on the digital re-packaging of government bonds through stablecoins; on the other hand is the Chinese monetary system, which chooses to be supported by gold. It is important to note that China is not returning to a traditional gold standard but is establishing a monetary discipline through gold. This actually reflects two different trust systems: the U.S. relies on technological innovation, while China relies on the stability of gold. This is how the future world may operate.

China Gold vs. U.S. Technology

Ryan: The scale of the GLI index continues to increase, such as 200 trillion, 300 trillion, or even more, and the reason behind this is that the governments of the U.S. and other countries are unlikely to default on their debts. If they face fiscal difficulties, the only solution is to continue printing money. This means we can expect these numbers to continue to grow over time. You mentioned that this phenomenon is actually the result of a capital war, and the main battleground of this capital war seems to be the confrontation between the U.S. and China.

You also mentioned that the world may be forming two monetary blocs: one is a stablecoin system supported by U.S. government bonds, which may also include strategic Bitcoin reserves; the other is a Chinese monetary system centered on gold. The People's Bank of China seems to be continuously purchasing large amounts of gold.

If we project this trend forward, a Chinese monetary bloc supported by gold may emerge, along with a monetary bloc supported by U.S. stablecoins and Bitcoin. Is that what you mean?

Michael:

Exactly, that is my point. If we view this confrontation as a capital war, one of the strategies of the U.S. is to maintain the volatility of gold prices. Because an increase in gold prices would significantly enhance China's economic power. Why do I say this? Although the U.S. also has a large amount of gold reserves (about 8,000 tons), this gold is not directly linked to the value of the dollar, as the dollar has long decoupled from gold. The U.S. does not rely on gold to support its monetary system, so the impact of rising gold prices on the U.S. is far less than on China.

Reports suggest that China may have secretly accumulated about 5,000 tons of gold, which is not far off from the U.S. reserves. This clearly poses a threat to the U.S. At the same time, China is not only focused on gold but may also leverage its technological advantages to conduct cyber attacks against the U.S. For example, through quantum computing, China could undermine the security of cryptocurrencies and even affect the infrastructure of Western societies, such as traffic signal systems or household devices. If Chinese malware is embedded in the global supply chain, it would pose significant risks to the U.S. and other countries.

Ryan: This is indeed a new frontier in the capital war. Which side do you think has the advantage, the U.S. cryptocurrency strategy or China's gold-backed strategy?

Michael:

From a personal perspective, I hope the U.S. can come out on top because I have great confidence in America's technological innovation capabilities. However, based on historical experience, gold tends to have an advantage in the long run.

Ryan: Does this also explain the significant rise in gold prices over the past few years?

Michael:

Yes, this is likely because China is actively accumulating gold. Although official data may not clearly show this, China, as the world's largest gold producer, is enhancing the credibility of its monetary system by accumulating gold reserves. China may promote gold-for-commodity swap transactions, allowing some countries to exchange gold for oil. These transactions would not be aimed at the general public but would be restricted to specific central banks. This is similar to the former gold standard system in the U.S.; although it is not a complete gold standard, the support and credibility of gold do play an important role in China's monetary system.

Cryptocurrency vs. Gold

Ryan: As some prestigious currencies gradually become collateral for broader fiat currencies, this could present new opportunities for investors. Looking ahead, if this trend materializes, do you think investors should hold both crypto assets and gold? For example, a portfolio of Bitcoin and gold? In this context, what are your predictions for the price trends of these assets over the next five to ten years?

Michael:

I think the answer can be viewed from two perspectives. If we approach it from the perspective of "capital war," gold and Bitcoin can be seen as key assets in the long-term competition between rivals. In the face of ongoing monetary inflation pressures, I believe investors should not choose between Bitcoin and gold but should hold both assets simultaneously. This strategy requires reasonable adjustments to volatility in the portfolio to balance risk and return.

Regarding inflation trends, I refer to the forecast data from the U.S. Congressional Budget Office. This data is recognized by both parties and has high transparency, predicting future debt growth and fiscal deficit situations until 2035. According to this data, the annual growth rate of U.S. federal debt may remain around 8%.

If we look back over the past 25 years, the total amount of U.S. federal debt has increased by about ten times. From 2000 to 2025, the growth rate of debt far exceeds the increase in the S&P 500 index (less than five times), while gold prices have risen 12 times during the same period. This indicates that the increase in gold prices has even outpaced the growth of debt.

According to the Congressional Budget Office's forecasts, in the coming decades, the ratio of U.S. public debt to GDP will rise from the current approximately 100% to 250%, effectively doubling the debt size. In other words, the speed of debt growth will be more than twice that of GDP growth, maintaining at least an annual level of 8%.

If gold prices continue to maintain their current relationship with federal debt, then by the mid-2030s, gold prices could easily reach $10,000 per ounce, and by 2050, they could even touch $25,000.

As for Bitcoin, we can refer to its current ratio with gold—about 25 to 27 times. If we extrapolate based on this ratio, Bitcoin's price could also see significant growth. Specific price predictions will require further analysis in conjunction with market dynamics, but from a long-term trend perspective, the potential of these assets is worth paying attention to.

Four-Year Cycle

Ryan: This is a very interesting question, and I represent cryptocurrency investors in asking you. We are all very concerned about the four-year cycle of cryptocurrencies, such as the Bitcoin halving event, which has occurred three times. So how does your global liquidity model view the four-year cycle of Bitcoin and crypto assets? Especially now that we are at the end of the fourth cycle, with the prices of crypto assets having significantly declined, investors are concerned about whether this cycle has ended. What are your thoughts on this?

Michael:

In short, I have analyzed the relationship between crypto assets and global liquidity, but I have not found clear evidence of a four-year cycle. While I know some people have proposed such a viewpoint and they may be right, my research did not reveal any obvious cyclical patterns. Of course, the Bitcoin halving event may impact the market, but I cannot determine its specific effect. In fact, I have observed longer cycles, such as debt refinancing cycles, which typically last five to six years. If the halving cycle primarily affects supply, it may indirectly reflect changes in demand, which does not completely align with the cyclical fluctuations in the global liquidity model. Nevertheless, the current market seems to show signs of convergence, which may require investors to remain cautious.

Ryan: So, if we set aside the unique four-year halving cycle of the cryptocurrency industry and look solely from your global liquidity model, can we conclude that the market is currently in the late stage of a cycle? The crypto market is indeed at a significant juncture; do you think this cycle is about to end, or is there still a possibility for it to continue?

Michael:

I want to clarify that trends and cycles are two distinctly different concepts, and in a portfolio, you need to consider the performance of both simultaneously. Typically, you would have a core long-term trend investment while also needing a tactical dynamic adjustment to respond to cyclical market fluctuations. The allocation ratio actually depends on personal preferences and how you find a balance between core assets and tactical adjustments.

Generally, this asset allocation strategy varies with age. For example, in the U.S., target-date funds are very popular in retirement plans. These funds dynamically adjust asset allocation based on the investor's age, gradually increasing the proportion of fixed-income assets as one ages, while younger individuals tend to hold more stocks. A similar logic can be applied to the allocation of tactical and core assets. If I were relatively young, I might allocate more funds to core assets, while the proportion for tactical adjustments would be lower. Conversely, if I were older, I might pay more attention to cyclical changes because if my investment horizon is only ten years, I wouldn't want to experience a downturn in asset prices in my later years. For younger individuals, with a longer investment horizon, it is easier to withstand the risks brought by cyclical fluctuations.

Therefore, this is essentially a matter of personal choice. I believe that the allocation of core assets should focus on the ability to combat monetary inflation. This includes Bitcoin, gold, high-quality residential real estate, and high-quality stocks that can maintain pricing power. These assets typically perform well in an inflationary environment. In fact, this investment strategy is very similar to Warren Buffett's investment philosophy, which emphasizes choosing companies with high growth potential and stable profit margins.

From a tactical perspective, when the market experiences cyclical changes, you need to adjust part of your portfolio to reduce risk. In the past few weeks, we have not been optimistic about the ongoing trends in the market, so we advise against chasing risk and reducing extreme positions. Because when the market experiences significant volatility, withdrawing these positions can become very difficult.

AI Bubble

Ryan: Another hot topic now is the AI bubble. Some tech optimists and firm believers in Silicon Valley believe that artificial intelligence represents a new industrial revolution. They believe that AI can significantly enhance productivity, drive GDP growth, and even break through the limitations of traditional economic cycles.

Michael, I want to ask how your liquidity model applies to discussions among other investors. In such a world, does your cyclical model still apply? What are your thoughts on the AI bubble? Do you think there is currently a bubble?

Michael:

History tells us that this time will be no different. We can look back at the bubble in the Japanese stock market. When I first entered this industry, the Japanese stock market was in a state of extreme inflation, and many believed Japan would dominate the global economy. However, it turned out that this optimism did not last long. After the bubble burst in the Japanese market, the economy fell into a long period of stagnation. At that time, there was even a famous movie about Japan's economy taking over the world, but it ultimately became a warning about the bubble's collapse.

Next, consider the tech bubble of 2000. Many companies were thought to be world-changers, but in the end, very few achieved long-term success. A similar situation occurred in the biotechnology industry. In the mid-20th century, biotechnology was considered the future, but now it has become very difficult to raise funds for biotech projects. These examples all indicate that bubbles and valuation issues are cyclical phenomena. There is no doubt that the AI bubble may follow similar patterns.

However, it is important to note that we are discussing stock market valuations, not the technology itself. For instance, during the tech bubble of 2000, while technology indeed became a part of our lives, this was a separate issue from market valuations. Similarly, railroads were a great innovation in the mid-19th century, but very few profited from railroad stocks. AI may bring profound technological changes, but that does not mean its market valuation will not undergo cyclical adjustments.

Global Liquidity Constraints

Ryan: Returning to the question we started with, can global liquidity serve as a universal theory to explain the market? You mentioned earlier that it can almost do so, but not completely. So, in what ways can global liquidity fail to explain market changes?

Michael:

While global liquidity is a very important market indicator, there are many other factors that can influence the market. For example, when extreme innovations occur, they may change market trends, and these changes are often unpredictable through liquidity. Additionally, liquidity is more suitable for macro-level cyclical analysis, but when delving into specific areas, such as stock selection, it becomes very difficult. For example, global liquidity can help us determine whether we should invest in a certain industry, but it cannot tell us whether Amazon will perform better than Walmart or Costco. This type of micro-level analysis requires support from many other indicators, and global liquidity cannot cover all the details.

Moreover, there are geopolitical factors. The impact of geopolitical events on the market is often short-term; historically, these shocks tend to be absorbed by the market over the long term. For instance, if a major conflict arises between Trump and Xi Jinping, the market may decline in the short term, but in the long run, the impact of such events will gradually diminish.

Ryan: I think the value of your model lies in its ability to help investors find investment signals from macro factors like global liquidity and monetary policy. Do you think investors can filter out the noise in the market by focusing on the global liquidity index and your research findings? Can this be used to tell the overall story of the market with your charts and data?

Michael:

I hope so. The global liquidity index can serve as a comprehensive statistical indicator to help investors filter out overly complex micro-information. While not everyone may be suited to use this index directly, as some may require more in-depth data analysis, we can also provide such services. But if you just need a simple and clear reference number, then the global liquidity index is indeed a very effective tool.

In my experience, I have found that liquidity is more important for understanding the market than GDP growth or other indicators that economists focus on. I may be skeptical about the role of traditional economics. In fact, in economics, those indicators that are easiest to measure are often considered the most important, but the reality may not be so. It's like a drunk person looking for their keys under a streetlight, not because they lost them there, but because there is light. Many studies in economics face similar issues, focusing too much on measurable indicators while neglecting what is truly important.

Outlook for the Next 3-6 Months

Ryan: Last question, Michael. What are the main aspects you are focusing on in the next three to six months? What are your expectations for the fundamental trends in the market?

Michael:

Currently, I am more focused on the dynamics of the repurchase market in the next three to six hours and three to six days, as this may be a key factor influencing trends in the coming months. Recently, the scale of the repurchase market has been expanding, which may put some pressure on the Federal Reserve. If leveraged positions in the market fail and trigger unwinding operations, it could further evolve into a larger financial crisis, significantly impacting the entire market.

This could very likely mark the end of the cycle. The key question is, what are the current policy goals of the government? For example, officials appointed by Trump, especially Steven Mnuchin, have expressed a desire to reduce the balance sheet while also wanting to lower interest rates. These two policy goals seem contradictory, but there may be a deeper logic behind them.

Lowering interest rates can directly stimulate the real economy, such as reducing mortgage rates, while also enhancing the competitiveness of U.S. exports by weakening the dollar. On the other hand, reducing the balance sheet may be aimed at redistributing economic activity, shifting more wealth from financial markets (Wall Street) to the real economy (Main Street). This is actually a policy that supports the real economy rather than being entirely focused on Wall Street, but it does reduce the optimism in financial markets.

Overall, the current policies of the Federal Reserve do not seem to support a bull market on Wall Street, but rather lean towards maintaining a range-bound market environment.

Assets Worth Holding

Ryan: **You just mentioned that the Federal Reserve's *quantitative easing* policy may gradually shift towards quantitative easing for government bonds, which is also a trend you are closely monitoring. In such an economic environment, which assets do you think are worth holding?**

Michael:

In the current environment, I believe we should focus on assets that can gain more momentum from real economic growth. For example, commodity assets are expected to perform well, and U.S. defense-related stocks are also worth considering. Additionally, as a short-term tactical investment, five-year government bonds may also be a good choice, especially during periods of high market volatility, as they can provide a degree of stability.

However, these short-term strategies do not change the core viewpoint of long-term investments. Monetary inflation is likely to persist in the future, so holding Bitcoin and gold in the investment portfolio is very important. These two asset classes typically perform well in an inflationary environment, and the best investment opportunities often arise during periods of market weakness. The current market may be gradually entering a weak phase, providing investors with an excellent opportunity to consider increasing their allocations to Bitcoin and gold to optimize long-term returns.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。