"Converting financial wealth into consumable currency requires selling it (or collecting its returns), and this is often the key point where bubbles turn into crashes."

Author: Ray Dalio

Compiled by: Deep Tide TechFlow

Although I am still an active investor addicted to the investment game, at this stage of my life, I also bear the role of a teacher, trying to impart my understanding of how reality works and the principles that help me cope with challenges. As a global macro investor, I have over 50 years of experience and have drawn many lessons from history, so most of what I share is naturally related to this.

This article mainly discusses the following points:

The important distinction between wealth and money;

How this distinction drives the formation and bursting of bubbles;

How this dynamic, accompanied by a significant wealth gap, can burst bubbles, leading to not only financial crashes but also potentially triggering severe social and political turmoil.

Understanding the distinction and relationship between wealth and money is crucial, especially in the following two aspects:

How bubbles form when the scale of financial wealth is significantly larger than the scale of money;

How bubbles burst when there is a demand for money, leading to the sale of wealth to obtain currency.

This very basic and easy-to-understand concept about how things operate is not widely recognized, but it has helped me greatly in my investment process.

The core principles to understand include:

Financial wealth can be created very easily, but it does not truly represent its real value;

Financial wealth itself has no value unless it is converted into consumable currency;

Converting financial wealth into consumable currency requires selling it (or collecting its returns), and this is often the key point where bubbles turn into crashes.

Regarding "financial wealth can be created very easily, but it does not represent its real value," for example, if a founder of a startup sells shares worth $50 million and values the company at $1 billion, then this founder becomes a billionaire.

This is because the company is considered to be worth $1 billion, even though there is no real backing close to $1 billion behind that wealth figure. Similarly, if a buyer of a publicly traded stock purchases a small amount of shares from a seller at a specific price, then all shares will be valued at that price, and this valuation method can yield the total wealth the company possesses. Of course, these companies may not truly be worth those valuations, as the value of assets ultimately depends on the price at which they can be sold.

Regarding "financial wealth is essentially worthless unless converted into currency," the reason is that wealth cannot be consumed directly, while money can.

When the scale of wealth far exceeds the scale of money, and those who possess wealth need to sell it in exchange for money, the third principle comes into play: "Converting financial wealth into consumable currency requires selling it (or collecting its returns), and this is often the key point where bubbles turn into crashes."

If you understand these concepts, you will be able to grasp how bubbles form and how they burst into crashes, which will help you predict and respond to bubbles and crashes.

It is also important to know that, although both money and credit can be used to purchase goods, there are the following distinctions between them:

a) Money can complete transactions, while credit incurs debt that needs to be settled in the future by obtaining money;

b) The creation of credit is relatively easy, while money can only be created by central banks.

While people may think that purchasing goods requires money, this is not entirely correct, as goods can also be purchased through credit, which incurs debt that needs to be repaid. This is often the foundational basis of bubbles.

Next, let's look at an example.

Although the mechanisms of all historical bubbles and crashes are fundamentally the same, I will use the bubble from 1927-1929 and the crash from 1929-1933 as an example. If you think about the bubble of the late 1920s, the crash from 1929-1933, and the actions taken by President Roosevelt in March 1933 to mitigate the crash from a mechanistic perspective, you will see how the principles I just described come into play.

Where does bubble money come from? How do bubbles form?

So, where does all the money that drives the stock market up and ultimately forms bubbles come from? And what makes it a bubble?

Common sense tells us that if the existing money supply is limited and everything needs to be purchased with money, then buying something means pulling funds from somewhere else. The things from which funds are pulled may see their prices drop due to being sold, while the prices of the things being purchased will rise.

However, in the late 1920s and now, **what drives bubbles is not money, but *credit*. Credit can be created without money to purchase stocks and other assets, thus forming bubbles. The dynamic at that time—this is also the most classic dynamic—was that credit was created and borrowed to purchase stocks, leading to the creation of debt that needed to be repaid. When the money needed to repay the debt exceeds the returns generated by the stocks, financial assets must be sold, leading to a drop in asset prices, and the dynamic of the bubble begins to reverse, ultimately forming the dynamic of a crash.

The basic principles driving the dynamics of bubbles and crashes are:

When the purchase of financial assets is supported by a significant growth in credit, and the total amount of wealth continues to rise relative to the total amount of money (wealth far exceeds money), a bubble will form. When wealth needs to be sold in exchange for money, it will lead to a crash. For example, during the period from 1929 to 1933, stocks and other assets had to be sold to repay the interest on the debt incurred to purchase them, causing the dynamic of the bubble to begin to reverse.

Naturally, the more borrowing and purchasing of stocks, the better the stock performance, and more people will want to buy stocks. These buyers do not need to sell other assets to complete their purchases because they can buy stocks through credit. As this behavior increases, credit begins to tighten, and interest rates rise. This is due both to the strong demand for borrowing and the fact that the Federal Reserve allows interest rates to rise (i.e., tightening monetary policy). When borrowing needs to be repaid, stocks must be sold to obtain funds to repay the debt, leading to price declines, defaults on debts, a decrease in the value of collateral, and a further reduction in credit supply, causing the bubble to turn into a self-reinforcing crash, ultimately triggering the Great Depression.

How does the wealth gap burst bubbles and trigger crashes?

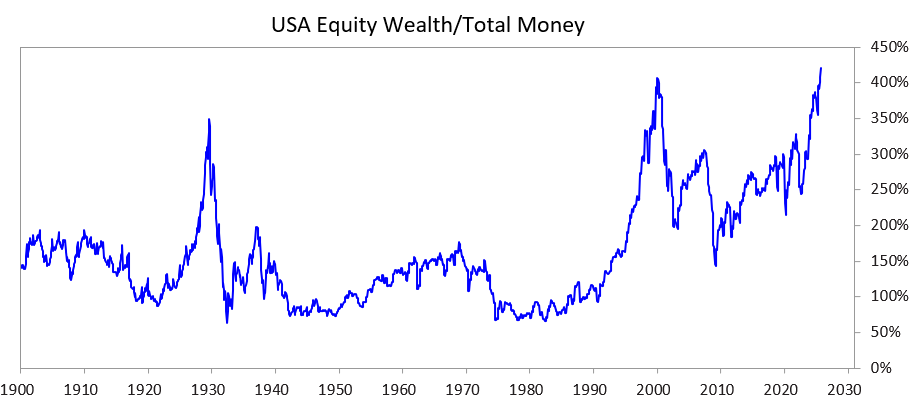

To explore how this dynamic can burst bubbles in the context of a significant wealth gap, leading to not only financial crashes but also social and political turmoil, I studied the following chart. This chart shows the gap between wealth and money in the past and present, specifically represented by the ratio of total stock value to total money value.

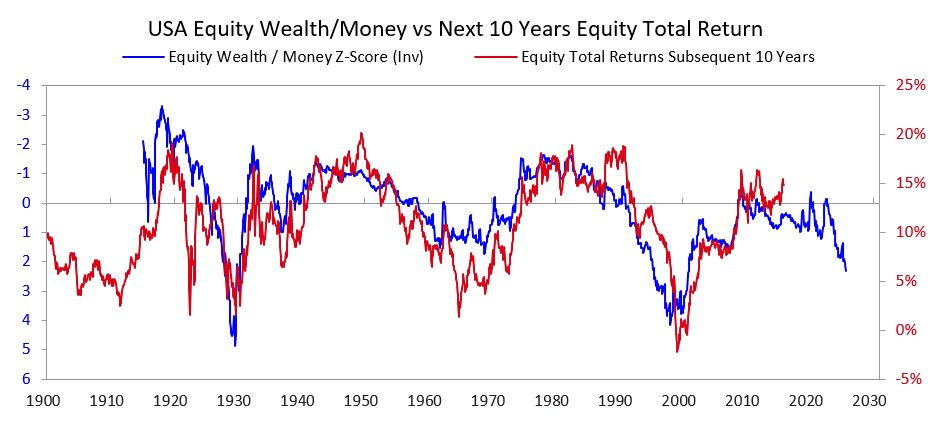

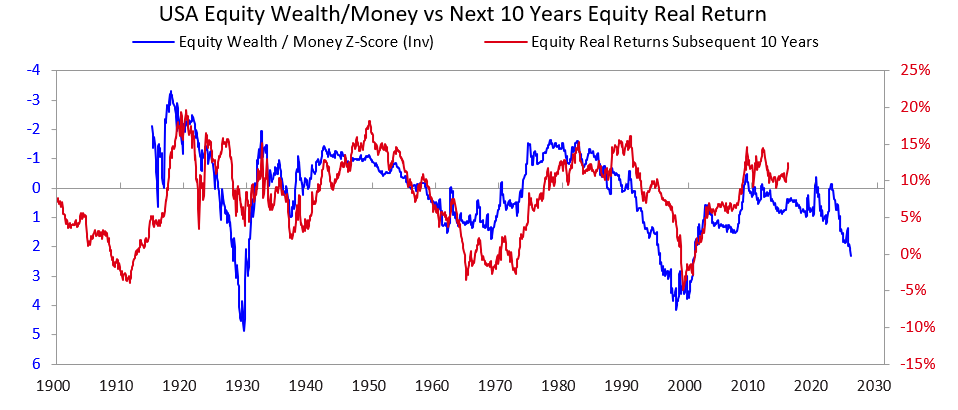

The next two charts show how this ratio becomes an indicator of nominal and real returns over the next decade. These charts speak for themselves.

When I hear people trying to determine whether a stock or the entire stock market is in a bubble by analyzing whether a company can generate enough profits in the future to justify its current stock price, I think to myself that they do not truly understand the dynamics of bubbles. While long-term investment returns are certainly important, they are not the primary reason for a bubble's burst. Bubbles do not burst because people suddenly realize one morning that income and profits are insufficient to support current prices. After all, whether there is enough income and profit to provide a good investment return often takes years or even decades to become clear.

The principle to keep in mind is:

The reason bubbles burst is that the inflow of funds into assets begins to dry up, and holders of stocks or other wealth assets need to sell these assets to obtain funds for certain purposes (most commonly to repay debts).

What usually happens next?

When a bubble bursts, and there is insufficient money and credit in the market to meet the needs of financial asset holders, the market and economy will decline, and internal social and political turmoil will often intensify. Especially in the presence of a significant wealth gap, this dynamic will further exacerbate the divide and anger between the wealthy (who tend to lean right) and the poor (who tend to lean left).

Taking the case from 1927 to 1933 as an example, this dynamic led to the Great Depression and triggered severe internal conflict, particularly the opposition between the wealthy and the poor. This series of events ultimately led to President Hoover being ousted and President Roosevelt being elected.

Naturally, when a bubble bursts and is accompanied by a market and economic downturn, it often triggers significant political changes, large fiscal deficits, and the monetization of debt. In the example from 1927 to 1933, the market and economic downturn occurred from 1929 to 1932, while political changes came in 1932, prompting President Roosevelt to begin implementing large fiscal deficit policies in 1933.

President Roosevelt's central bank printed a large amount of money, leading to currency devaluation (for example, relative to gold). This currency devaluation alleviated the funding shortage and had the following effects:

a) Helped those systemically important debtors alleviate pressure and be able to pay interest on debts;

b) Increased asset prices;

c) Stimulated economic development.

Leaders who come to power during such times often implement many shocking fiscal policy changes, although it cannot be detailed here, it is certain that these periods are usually accompanied by significant conflict and major transfers of wealth. In Roosevelt's case, these situations prompted many significant fiscal policy changes to achieve the transfer of wealth from the top to the general public. For example, raising the top marginal income tax rate from 25% in the 1920s to 79%, significantly increasing estate and gift taxes, and funding the massive growth of social programs and subsidies. These policies also led to significant conflicts both domestically and internationally.

This is a classic dynamic. Throughout history, many leaders and central banks have repeated similar practices in many countries and over many years, so many times that it is difficult to list them all. By the way, before 1913, the United States did not have a central bank, and the government did not have the ability to print money, so bank failures and deflationary economic depressions were more common. But in either case, bondholders typically fared poorly, while gold holders performed well.

Although the case from 1927 to 1933 is a classic example of a bubble bursting cycle, it represents a more extreme situation. Similar dynamics can also be observed in other periods, such as the events that prompted President Nixon and the Federal Reserve to take similar actions in 1971, as well as the occurrence of nearly all other bubbles and crashes (such as the Japanese economic bubble from 1989 to 1990, the internet bubble in 2000, etc.). These bubbles and crashes are often accompanied by other typical characteristics, such as markets attracting a large number of inexperienced investors driven by market enthusiasm, who buy on leverage and ultimately suffer significant losses and feel angry.

This dynamic has persisted for thousands of years, and when these conditions exist (i.e., demand for money exceeds supply), wealth must be sold to obtain funds, leading to bubble bursts, defaults, currency printing, and subsequent economic, social, and political issues. In other words, the imbalance between financial wealth (especially debt assets) and money, as well as the process of converting financial wealth into money, is the fundamental cause of bank runs—whether in private banks or government-controlled central banks. These runs either lead to defaults (which mainly occurred before the establishment of the Federal Reserve) or prompt central banks to create money and credit to support those "too big to fail" institutions to help them repay loans and avoid failure.

Please keep the following points in mind:

When the promise of currency delivery (i.e., debt assets) far exceeds the existing amount of money, and financial assets need to be sold to obtain funds, be wary of the possibility of a bubble burst and ensure your protection. For example, do not hold a large credit exposure and have some gold as a hedge. If this situation occurs during a time of significant wealth disparity, also be alert to the potential for major political and wealth changes and take measures to protect yourself from the impact.

While interest rate hikes and credit tightening are the most common reasons for assets being sold to obtain funds, any factors that lead to increased demand for funds (such as wealth taxes) and actions to sell financial wealth to meet funding needs can trigger similar dynamics.

When a significant gap between money/wealth exists alongside inequality in wealth distribution, this situation should be viewed as a very high-risk environment, requiring extra caution.

From the 1920s to Now: The Cycle of Bubbles, Crashes, and New Orders

(If you do not wish to learn about the brief history from the 1920s to now, you may skip this section.)

While I previously mentioned how the bubble of the 1920s led to the crash and Great Depression from 1929 to 1933, to quickly supplement the background information, that crash and the subsequent depression ultimately prompted President Roosevelt to default on the U.S. government's promise to provide hard currency (gold) at a fixed price in 1933. The government printed a large amount of money, and the price of gold rose by about 70%.

I will skip over how the re-inflation from 1933 to 1938 led to the tightening in 1938; how the "recession" from 1938 to 1939 created conditions for the economy and leadership, combined with the geopolitical dynamics of Germany and Japan rising to challenge British and American dominance, which together led to World War II; and I will also skip over how the classic long-cycle dynamics took us from 1939 to 1945—when the old monetary, political, and geopolitical order collapsed, and a new order was established.

I will not delve into the reasons in detail, but it is important to note that these events made the United States very wealthy (holding two-thirds of the world's currency, namely gold at the time) and powerful (producing half of the world's GDP and becoming a military dominant force). Therefore, in the new monetary order established by the Bretton Woods Agreement, currency was still based on gold, with the dollar pegged to gold (other countries could purchase gold at $35 per ounce with the dollars they obtained), and the currencies of other countries were also pegged to gold.

However, between 1944 and 1971, U.S. government spending far exceeded tax revenues, leading to significant borrowing and selling in the form of debt, creating gold claims that far exceeded the central bank's gold reserves. Realizing this, other countries began to exchange paper currency for gold. This led to a tightening of money and credit, prompting President Nixon in 1971 to take actions similar to those of President Roosevelt in 1933, again devaluing fiat currency relative to gold, causing the price of gold to soar.

In short, from then until now:

a) Government debt and its servicing costs have significantly increased relative to tax revenues, especially during the period from 2008 to 2012 following the global financial crisis of 2008, and after the financial crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020;

b) The income and value gap has expanded to its current enormous level, leading to irreconcilable political divisions;

c) Due to speculation supported by credit, debt, and new technologies, the stock market may be in a bubble state.

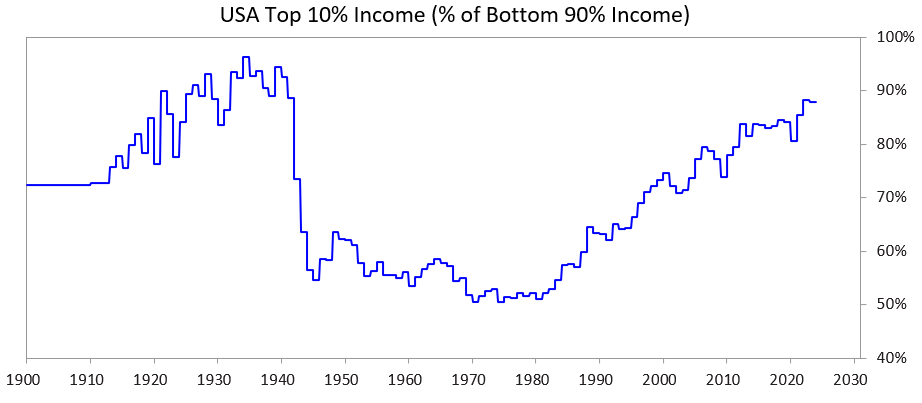

The following chart shows the income share of the top 10% compared to the bottom 90%—it is clear that today's income gap is extremely large.

Current Situation

Governments in the United States and other democratically governed, over-indebted countries now face a dilemma:

a) They cannot continue to increase debt as they did in the past;

b) They cannot bridge the fiscal gap through sufficient tax revenue growth;

c) They cannot significantly cut spending to avoid deficits and stop further increases in debt.

They are stuck in a stalemate.

Detailed Analysis

These countries cannot borrow enough funds because the free market's demand for their debt has become insufficient. (The reason is that these countries are over-indebted, and creditors already hold too many debt assets.) Additionally, international creditors (such as China) are concerned that war conflicts may lead to debt defaults, thus reducing their purchases of bonds and converting debt assets into gold.

They cannot solve the problem through sufficient tax revenue growth because if they tax the wealth concentrated among the top 1%-10%:

a) These wealthy individuals may choose to leave, taking their tax contributions with them;

b) Politicians may lose the support of the top 1%-10%, whose backing is crucial for funding expensive election campaigns;

c) It may lead to a market bubble burst.

At the same time, they cannot cut enough spending and welfare because doing so may be politically or even morally unacceptable, especially since such cuts would disproportionately affect the bottom 60%…

Thus, they find themselves in a stalemate.

For these reasons, all democratic governments with high debt, significant wealth gaps, and severe value discrepancies are facing dilemmas.

Under current conditions, combined with the operation of democratic political systems and human nature, politicians continuously promise quick solutions to problems but fail to deliver satisfactory results, leading to their rapid ousting, only to be replaced by a new batch of politicians promising quick fixes, who also fail and are replaced again, creating a cycle. This is why countries like the UK and France—whose systems allow for rapid leadership changes—have experienced four prime ministers in the past five years.

In other words, we are witnessing a classic pattern of the "long cycle" phase. This dynamic is very important and worth understanding in depth, and it should now be evident.

Meanwhile, the stock market and wealth prosperity are highly concentrated in top AI-related stocks (such as the "Magnificent Seven") and a few super-rich individuals. AI is replacing human jobs, exacerbating inequality in wealth and currency distribution, as well as the wealth gap between individuals. Similar dynamics have occurred multiple times in history, and I believe there is a high likelihood of significant political and social backlash, which will at least significantly alter wealth distribution, and in the worst-case scenario, could lead to severe social and political chaos.

Next, let us explore how this dynamic, along with the enormous wealth gap, poses problems for monetary policy and may trigger wealth taxes, thereby bursting bubbles and leading to economic collapse.

What Does the Data Show?

I will compare the top 10% of wealth and income earners with the bottom 60% of wealth and income earners, choosing the bottom 60% because this group represents the majority.

In short:

The wealthiest individuals (top 1%-10%) possess far more wealth, income, and stock assets than the bottom 60%.

For the wealthiest individuals, their wealth primarily comes from the appreciation of asset values, which is not taxed until the assets are sold (unlike income, which is taxed when earned).

With the boom in AI, these gaps are widening and may further accelerate.

If wealth is taxed, it will require selling assets to pay the taxes, which could lead to a bubble burst.

More specifically:

In the United States, the top 10% of households are well-educated and economically productive, earning about 50% of total income, holding about two-thirds of total wealth, owning about 90% of stock assets, and paying about two-thirds of federal income tax. These figures are steadily increasing. In other words, their economic situation is very good, and their contributions to society are significant.

In contrast, the bottom 60% of households have lower education levels (for example, 60% of Americans read below a sixth-grade level), relatively low economic productivity, collectively earning only about 30% of total income, holding only about 5% of total wealth, owning about 5% of stock assets, and paying less than 5% of federal taxes. Their wealth and economic prospects are relatively stagnant, leading to financial pressure.

Naturally, this situation creates immense pressure for the redistribution of wealth and funds from the top 10% to the bottom 60%.

Although the United States has never imposed a wealth tax in its history, calls for wealth taxes at both state and federal levels are growing louder. Why impose a wealth tax now when it wasn't done before? The answer is simple—because wealth is concentrated there. In other words, the top 10% have become wealthier primarily through asset appreciation that has not been taxed, rather than through labor income.

Wealth taxes face three major issues:

The wealthy can choose to relocate, and once they leave, they take not only their talents, productivity, income, and wealth but also their tax contributions. This will weaken the regions they leave while enhancing the regions they move to.

Implementing a wealth tax is very difficult (you may already understand the specific reasons, so I won't elaborate further to avoid making this article longer).

A wealth tax will divert funds from investment activities that support productivity enhancement to the government, and assuming the government can effectively manage these funds to make the bottom 60% more productive and wealthy is almost unrealistic.

For these reasons, I would prefer to see an acceptable tax rate (e.g., 5%-10%) on unrealized capital gains, but that is another topic that needs to be discussed separately.

Postscript: How Will a Wealth Tax Be Implemented?

In future articles, I will explore this issue in more detail. In simple terms, U.S. household balance sheets show a total wealth of about $150 trillion, but the amount in cash or deposits is less than $5 trillion. Therefore, if a wealth tax of 1%-2% were imposed annually, the required cash would exceed $1-2 trillion, while the existing pool of liquid cash is only slightly above this figure.

Any similar policy could lead to asset bubbles bursting and trigger an economic recession. Of course, a wealth tax would not be imposed on everyone but rather targeted at the wealthy. While this article does not delve into specific numbers, it is clear that a wealth tax could have the following impacts:

Force mandatory sales of private and public equity, thereby depressing valuations;

Increase demand for credit, potentially raising borrowing costs for the wealthy and the overall market;

Encourage the transfer of wealth to tax-friendly regions or offshore tax havens.

If the government imposes a wealth tax on unrealized gains or illiquid assets (such as private equity, venture capital holdings, or even concentrated public equity positions), these pressures will be particularly pronounced and could even trigger more severe economic problems.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。