Author: Haotian

Let's talk about the highly publicized bidding event for the $USDH stablecoin by @HyperliquidX.

On the surface, it appears to be a battle for interests among several issuers like Frax, Sky, and Native Market, but in reality, it is a "public auction" for the right to mint stablecoins, which will change the rules of the game in the subsequent stablecoin market.

Combining thoughts from @0xMert_, I would like to share a few viewpoints:

1) The competition for the USDH minting rights exposes a fundamental contradiction between the demand for native stablecoins in decentralized applications and the need for unified liquidity in stablecoins.

In simple terms, every mainstream protocol is trying to have its own "printing rights," but this will inevitably lead to liquidity being fragmented and divided.

To address this issue, Mert proposed two solutions:

1. Align the stablecoins in the ecosystem, where everyone agrees to use a common stablecoin and share profits proportionally. The problem arises: if USDC or USDT is the most widely accepted aligned stablecoin, would they be willing to share a significant portion of their profits with DApps?

- Build a stablecoin liquidity layer (M0 model) using Crypto Native thinking to create a unified liquidity layer, such as Ethereum as an interactive operational layer, allowing various native stablecoins to be seamlessly exchanged. However, who will bear the operational costs of the liquidity layer, and who will ensure the structural anchoring of different stablecoins? How will systemic risks caused by individual stablecoins losing their peg be resolved?

These two solutions seem reasonable but can only address the issue of liquidity fragmentation, as once the interests of each issuer are considered, the logic becomes inconsistent.

Circle relies on a 5.5% treasury yield to earn billions of dollars annually; why would they share with a protocol like Hyperliquid? In other words, when Hyperliquid qualifies to separate from traditional issuers of stablecoins, the "lying win" model of issuers like Circle will also be challenged.

The USDH bidding event can be seen as a demonstration against the "hegemony" of traditional stablecoin issuance. In my view, whether the rebellion succeeds or fails is not important; what matters is the moment of uprising.

2) Why do I say this? Because the rights to stablecoin profits will ultimately return to the value creators.

In the traditional stablecoin issuance model, companies like Circle and Tether essentially act as intermediaries. Users deposit funds, which they use to purchase treasury bonds or deposit in Coinbase to earn fixed lending interest, but they keep most of the profits for themselves.

Clearly, the USDH event aims to tell them that this logic has a bug: the real value creators are the protocols that handle transactions, not the issuers who merely hold reserve assets. From Hyperliquid's perspective, processing over $5 billion in transactions daily, why should they give up over $200 million in annual treasury yields to Circle?

In the past, the primary demand for stablecoin circulation was "safety without losing peg," so issuers like Circle, which incur significant "compliance costs," should rightfully enjoy this portion of profits.

However, as the stablecoin market matures and the regulatory environment becomes clearer, this portion of profit rights will likely shift to the value creators.

Therefore, in my view, the significance of the USDH bidding lies in defining a brand new rule for stablecoin profit distribution: whoever controls the real transaction demand and user traffic will have priority in profit distribution rights.

3) So what will the endgame be: will payment chains dominate the discourse, and issuers become "backend service providers"?

Mert mentioned a third interesting proposal: generating income from payment chains while traditional issuers see their profits approach zero. How should this be understood?

Imagine that Hyperliquid can generate hundreds of millions in revenue just from transaction fees in a year; in contrast, the potential treasury yields from managing reserves, while stable, become "optional."

This explains why Hyperliquid chooses to transfer the issuance rights instead of leading the issuance themselves, as it is unnecessary. Issuing would only increase "credit liabilities," and the profits gained would be far less enticing than the transaction fee profits from expanding trading volume.

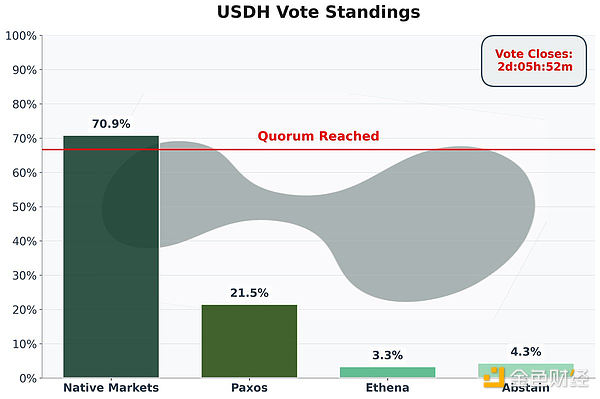

In fact, look at how the bidders reacted after Hyperliquid transferred the issuance rights; it proves everything: Frax promised to return 100% of the profits to Hyperliquid for HYPE buybacks; Sky offered a 4.85% yield plus a $250 million annual buyback; Native Markets proposed a 50/50 profit split, etc.

Essentially, the original battle for interests between DApps and stablecoin issuers has evolved into an "involution" game among issuers, especially as new issuers force old issuers to change the rules.

That's all.

Mert's fourth proposal sounds a bit abstract; if it comes to that, the brand value of stablecoin issuers may completely drop to zero, or the minting rights may be entirely unified under regulatory control, or it could be some form of decentralized protocol. It remains to be seen. That should still belong to a distant future.

In my view, this chaotic bidding for USDH can declare the end of the era where old stablecoin issuers could "lie win," and it is already significant to truly guide the rights to stablecoin profits back to the "applications" that create value!

As for whether it is "vote-buying" or whether the bidding is transparent, I actually think that is a window of opportunity before the GENIUS Act regulatory plan is truly implemented; just watching the excitement is enough.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。