Original | Vitalik Buterin

Translation | Odaily Planet Daily (@OdailyChina)

Translator | Dingdang (@XiaMiPP)

Editor's Note: Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin published an article titled "On idea-driven ideas" yesterday, exploring the roles and balance of "idea-driven" and "data-driven" thinking in decision-making, responding to Gabriel from Conjecture's criticism of his d/acc (defensive/decentralized/differential acceleration) framework. Gabriel believes that Vitalik's approach relies too heavily on "ideology" such as decentralization and should be more pragmatically oriented towards the overall value of humanity. Vitalik uses the metaphor of "materialism" and "positionism" in chess to point out that blockchain and decentralization are not just technical means but also carry the functions of community cohesion and collaborative division of labor. He acknowledges that ideology can interfere with rationality but emphasizes its necessity in complex decision-making and community collaboration, proposing to use data-driven choices to guide ideas and to use limited principles rather than comprehensive ideologies to guide actions.

A long time ago, in the century before the COVID-19 pandemic, I heard economist Anthony Lee Zhang make an interesting distinction between "idea-driven ideas" and "data-driven ideas."

"Idea-driven" means first establishing a macro philosophical framework—such as "markets are rational," "concentration of power is dangerous," or "time-tested traditions are wise"—and then deriving more specific conclusions through logical reasoning.

In contrast, "data-driven" starts from a null hypothesis, drawing conclusions through data analysis and accepting any results that the data leads to. The implication is clear: data-driven ideas seem more worthy of holding and promoting.

Last month, Gabriel from Conjecture criticized my approach to the d/acc issue. He believes that rather than starting from some "ideology" and then trying to make it compatible with other human goals, it is better to take a pragmatic stance and neutrally seek strategies that can maximize the satisfaction of the entire set of human values.

Odaily Planet Daily Note: d/acc stands for defensive/decentralized/differential acceleration. It is a philosophy of technological development that advocates prioritizing defensive, decentralized, and differentiated strategies while technology accelerates, to ensure that technological progress maximizes the overall benefits for humanity while avoiding potential risks (such as concentration of power, technological abuse, or social inequality). It can be understood as a modification of "accelerationism" (which advocates for unrestricted technological progress), emphasizing selectively accelerating technologies that benefit humanity rather than blindly pursuing speed.

This viewpoint is not uncommon. But it raises a question: what role should things referred to as "ideology," "principles," "consolidated goals," or "consistent guiding thoughts" play in individual thinking? What are their limitations?

My views on this question can be summarized as follows:

- The world is too complex to derive every decision from scratch. For efficiency, we must leverage and reuse certain intermediate conclusions.

- Ideology is not only a tool for individual cognition but also a social construct. Communities need cohesion; if they cannot rely on shared ideas or narratives, they often coalesce around a person or a small group—which can lead to worse outcomes.

- Encouraging different people to pursue different specific goals helps form division of labor and collaboration.

- Ideology in reality is often a mixture of means and ends, and we must face this fact.

- Ideology can indeed interfere with rational thinking in various ways, which is a real and serious issue.

- Good decision-making requires finding a balance between "idea-driven" and "pragmatic modes" and establishing mechanisms to adjust ideas when necessary.

Decision-making in complex situations always has "structure"

Suppose you want to improve your chess skills. There is a common rule of thumb in the chess world: a queen is worth about nine pawns, a rook is worth five pawns, and a bishop or knight is worth three pawns.

Therefore, it is reasonable to exchange "one rook and one pawn" for "one bishop and one knight," but exchanging "one rook" for "one knight" is clearly not worth it.

This rule can lead to many tactical ideas. For example, you can look for opportunities to use a knight to "fork" two high-value pieces of your opponent—perhaps two rooks or one rook and one queen. This forces your opponent to choose to let your knight capture one of their strong pieces, and then use other pieces to capture your knight (the weaker piece) in exchange.

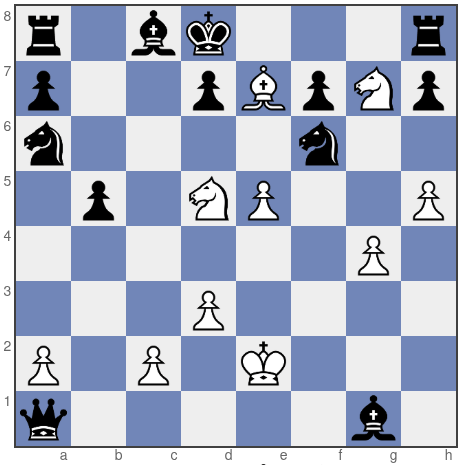

White to move. Moving the knight to f7 is a good move, but you must first know the rule "knight=3 pawns, rook=5 pawns" to quickly assess its value.

Here, the rules "queen=9 pawns, rook=5 pawns, knight/bishop=3 pawns" essentially serve as a generator of tactical inspiration, helping you start from a more effective point rather than searching blindly.

If we view this rule as a form of "ideology," given that pieces in chess are referred to as "material," we can call it "materialism."

Of course, some people partially or completely disagree with "materialism." Often, sacrificing material is worthwhile, such as to expose the opponent's king or to seize control of the center of the board. The value of material can also change depending on the situation. In endgames, I find that a single knight is usually more useful than a single bishop, while two bishops are often stronger than two knights. If a player focuses on these situational characteristics to formulate tactics, they might call themselves a "positionist."

Materialists and positionists may disagree in certain situations, such as whether to exchange two pawns for a bishop:

To capture h3 or not to capture? That is the question.

The ideal player might be able to combine materialism and positionism, flexibly switching based on the situation, somewhat akin to Hegelian synthesis.

But truly achieving this requires a clear set of judgment criteria—when to prioritize material factors and when to focus on positional factors, and this judgment itself is also a new form of ideology.

The value of principles in social collaboration

In modern society, to take effective action, one often must rely on collective power—hundreds, thousands, or even millions of people acting simultaneously towards the same goal. Some things can be pushed through money (or physical coercion), but that is ultimately limited; much of what we do actually relies more on intrinsic motivation and social motivation to truly be effective.

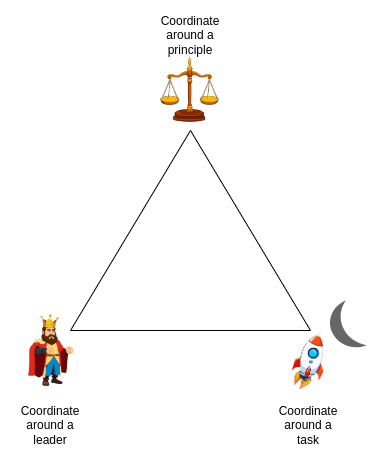

In my article on "Plurality," I mentioned that communities primarily have three forms of collaboration in this regard:

Collaborating around tasks is extremely powerful. If you can get a large number of people to believe that "landing on the moon" is very valuable, once they start acting, they will invest a great deal of effort, creativity, and energy to achieve that goal. Ethereum's transition from "proof of work" to "proof of stake" in 2022 is an example of such task-based collaboration for many community members.

However, tasks are one-time events, and you do not want the social capital accumulated after the task is completed to dissipate. The power of principles and leaders lies in their ability to continuously generate new tasks: when old tasks end, they can continue to point towards new, valuable work.

Collaborating around leaders has a well-known risk: leaders are fragile. History has countless examples showing that leaders can lose their sanity, or in more subtle but equally profound ways, their priorities and values can shift. This applies not only to individual leadership but also to situations where leadership is held by a group of people.

Collaborating around principles—especially those that are non-outcome-oriented (non-utilitarian)—may be more robust.

(Well-chosen) principles have a key characteristic that I call "galaxy brain resistance." The weakness of utilitarianism is that it can easily be circumvented by leaders using various clever arguments—they may claim that almost any action they choose can lead to optimal results due to some complex "four-dimensional chess" style second-order reasoning. The role of principles is to act as a brake on this tendency: "No matter how clever your reasoning is, there are some things we simply will not do because there is a clear and easily understandable bottom line in place."

From this perspective, a major flaw of ideology—it sometimes appears "dumb"—may actually become an advantage.

Another important form of collaboration is internal collaboration, which we often refer to as "motivation."

I find that some insights from interpersonal collaboration can actually be analogized to the different "sub-agents" within a person—these sub-agents may have different perspectives and goals. If there is a clear and consistent principle or goal within, it not only makes you more motivated in your work but also prevents you from going off track and rationalizing doing something wrong.

Solidifying goals into a division of labor

In organizations, if different people belong to different sub-departments, each undertaking specific missions, then having them possess different goals can actually be beneficial.

A company has a marketing department, a software development department, and many other departments. You do not want the marketing department's people to have overly divergent thoughts, pondering various ways to make the company successful; you want them to focus their energy on marketing.

This seems to deviate from pure utilitarianism, but strict division of labor and collaboration is precisely what allows a company to complete tasks in an orderly and stable manner.

I believe that this grand project of human civilization also has similar characteristics—we want different people to internalize and focus on different sub-goals of civilization.

One subtle but often underestimated reason for this: it makes performance measurable.

If an actor's goal is "to do all useful things," then whether they are self-improving or being held accountable externally, it is difficult to judge whether they are performing well or poorly.

But if the goals are more specific and narrow, it becomes clearer to assess how well they are being accomplished and where improvements can be made.

This benefit can be very significant—sometimes even enough to offset some collaborative errors that may arise between actors with different goals.

Ideology as a Hybrid of Means and Ends

So far, I have primarily viewed ideology as a means: it is a set of action propositions about how to achieve certain universally recognized goals.

In Gabriel's article, ideology is more about the goals themselves, specifically which goals should be prioritized.

In reality, ideology is always a complex and messy combination of both.

So, since ideology also involves goals, how should I incorporate this into my previous discussion?

Here, I will give a somewhat "lazy" answer: I believe that the goals we can specify enough to form an ideology or write down are, in essence, also a means.

Why do I say this? Let’s imagine a person who highly values freedom. Initially, they might say they cherish freedom because it leads to a more efficient economy and a more robust society.

But if you tell them there is a way to achieve a very efficient and robust economic society—yet it relies almost entirely on a lack of freedom. For example, you design an advanced computer to manage the economy, telling everyone where to work, while the robustness of society depends on a democratic voting mechanism held every month to adjust or completely replace the parameters of this computer.

This liberal individual would feel very uneasy upon hearing this proposal, as they know that if this plan were implemented, they would immediately start planning resistance.

Why is that? I believe that "entrenched values" are actually a strategy or prediction, while the true ultimate goals (the "victory conditions" they pursue) are very complex and difficult to interpret, hidden in a pile of conditions and preferences in each of our minds.

When this liberal hears about this efficient and robust yet unfree societal proposal, they realize that efficiency and robustness are like "material" in chess—they are important parts of winning the game, but they are by no means everything.

The Potential Negative Impact of Ideology

Radical supporters of climate change often say they support "degrowth" policies because it is the only way to prevent the Earth from overheating.

But if you propose using solar energy (or more extreme solar geoengineering) to prevent the Earth from overheating without affecting material wealth or capitalism, they can always enthusiastically come up with various reasons to explain why these proposals are unfeasible or would lead to too many "unintended consequences."

Cryptocurrency enthusiasts often say they want to improve global financial accessibility, establish credible property rights, and use blockchain to solve various social issues.

But if you present a method that can solve the same problems without relying on blockchain, they will similarly enthusiastically find various reasons to dismiss your proposal, perhaps because it is "too centralized" or "lacks sufficient incentive mechanisms."

These two examples are somewhat similar to the liberal I mentioned earlier, but not entirely the same.

It is reasonable to consider freedom as an ultimate goal (provided that freedom is not your only value), after all, freedom as a goal is deeply embedded in human genes through millions of years of evolution.

However, viewing the abolition of capitalism or the large-scale adoption of blockchain as the same ultimate goal is less reasonable.

I believe this is fundamentally the failure mode we must be wary of: elevating something to the status of an ultimate goal when it is not, resulting in serious harm to the underlying goals we truly wish to achieve.

"But I have more and stronger pieces in hand, so even if I am checkmated, I am the true winner in spirit."

How I Reconcile These Two Views

In the previous sections, I pointed out two positive uses of what you might call "ideology," "principles," or "idea-driven thoughts":

- As a "department" of ideology-driven thinking and action. Just as a company has a dedicated marketing department, society has reason to establish a "department" responsible for protecting the environment; similarly, chess players should have dedicated thought processes to answer questions like "What strategy can help me capture my opponent's pieces while preserving my own?"

- As a coordinating tool of principles. Gathering around an ideology is more resilient and less prone to failure or manipulation than rallying around a leader or elite.

Social movements typically encompass both. Externally, they strive to defend a principle, reducing society's over-reliance on elites; internally, they focus on specific themes to foster valuable ideas and strategies for improving the world. For example, liberal economists defend social freedom while inventing beneficial ideas like prediction markets and refining congestion pricing; environmentalists advocate politically to prevent irreversible environmental damage while promoting technological innovations like clean energy and synthetic meat.

The Two Failure Modes I See

First, certain instrumental goals become overly entrenched and are pursued to extremes, undermining the original fundamental goals.

Second, coordination around infinite goals easily slips into a pattern where an elite class interprets the goals.

This is what Balaji Srinivasan refers to as "democracy is essentially the rule of Democrats," and the phenomenon where the effective altruism movement is criticized for shifting from broadly promoting effective charity to narrowly addressing AI safety and only funding those within their own circles.

I propose two compromise solutions to try to balance these pros and cons:

- Data-driven choice of ideology. Maintain a set of knowledge themes that can generate hypotheses, then use data analysis to decide which to prioritize and which to ignore. Bryan Caplan does this well. He has a strong liberal ideology but also values empirical rigor, which is why the core issues he supports (such as more open immigration, reducing education, and relaxing housing regulations) are well-supported by evidence. Although the liberalism he subscribes to leads him to believe in many views I disagree with, he rarely promotes those lacking substantial data support. You may still disagree with his extreme views, but in my opinion, he is more rational among extremists, so I believe his approach has merit.

- Principles, not ideology. The subtle distinction between these two words is that principles are usually restrictive, while ideologies tend to be comprehensive. Principles provide you with a set of do's and don'ts and then stop; ideologies have no boundaries, and you can pursue them indefinitely. This is just a rough categorization, but I believe it is significant. Focusing the social coordination function on principles that "avoid going off track" allows a movement (or individual) to benefit from more pragmatic thinking under normal circumstances while maintaining considerable robustness.

The complexity of the world and the internal structure of our (individual and collective) minds means that directly "rationally weighing all values and making the best data-driven choice" often fails in various ways in practice. At the same time, over-reliance on a certain structure can also collapse, sometimes even worse. Only by finding a balance between the two is it most likely to gain more benefits while minimizing the drawbacks of both sides.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。