The "Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures" of the FTX Recovery Trust, while superficially cloaked in compliance, is in fact a structural exclusion mechanism.

Written by: Daii

A global plunder disguised as a procedural formality is quietly beginning.

In early July 2025, a motion document from the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Delaware struck like a thunderclap, hitting the most silent group among global FTX creditors.

This seemingly rational and concise motion seeks court approval for the "Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures." Once this procedure is initiated, it could result in creditors from 49 countries and regions, including China, being unable to receive any compensation.

From Mt. Gox to Celsius, from Voyager to Genesis, we have witnessed lengthy processes and slow payouts, but we have never seen a bankruptcy compensation openly set up a "prove your innocence first, or automatically forfeit" barrier for creditors from 49 countries.

This is not a compensation claim; it resembles a "default forfeiture" drill.

We must see clearly: this is not just a legal game; it is a clash of systems—globalization of internet assets vs. localization of financial regulation. If this motion is approved in Delaware, similar bankruptcy trusts will use this document as a "template."

You may still be watching, but the process has already begun.

This time, we must fight on two fronts:

On one hand, before the court hearing on July 22, we must do everything possible to block the motion itself and make the judge hear the voices of the restricted creditors;

On the other hand, if the procedure is indeed passed, we must initiate a class action lawsuit against the FTX Recovery Trust for both breach of contract and tort, making the "cost of forfeiture" far exceed "reasonable compensation."

Justice should not be undermined by procedures. This should be the awakening moment for FTX creditors from 49 countries.

Before that, it is necessary to understand the background of this motion.

1. Why is there this motion? — From the perspective of the FTX Recovery Trust

Opening the motion submitted to the Delaware Bankruptcy Court on July 2, 2025, we see this opening statement:

FTX's infamous prepetition business activities violated cryptocurrency-related laws and regulations in various countries around the world, often flagrantly. Today, certain creditors of the FTX Recovery Trust reside in jurisdictions that continue to have laws and regulations that restrict cryptocurrency transactions.

This sentence acts like a mirror, reflecting the sharp game between "losing money" and "breaking the law"—the Recovery Trust must choose between a dilemma.

1.1 Risks

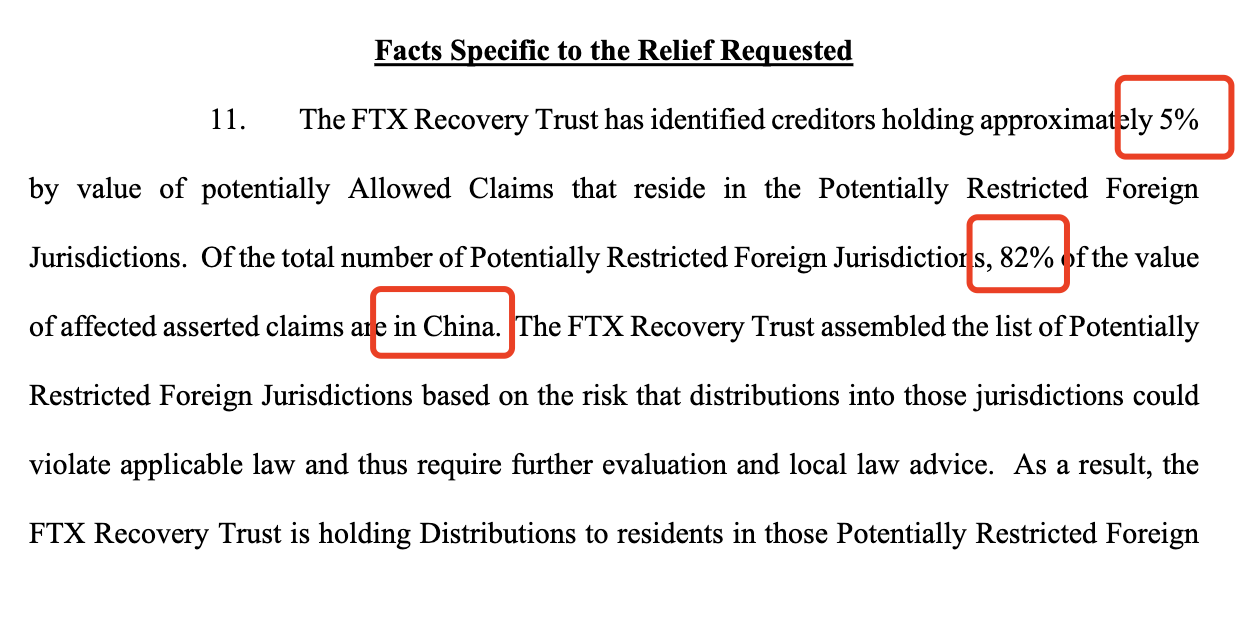

Attachment B of the motion lists 49 "potential restricted jurisdictions," where the creditors account for about 5% of the total identifiable claims. Among these, Chinese creditors account for 82% of that value (Cointelegraph).

In these regions, at least 16 countries prohibit cryptocurrency payments, and 9 countries have written digital asset payment behaviors into criminal law, with the most severe penalties reaching up to 10 years in prison (Cointelegraph). There is also the case in Tunisia: in 2018, the central bank issued a comprehensive ban, and in 2021, a 17-year-old was arrested and prosecuted for "illegal foreign exchange trading" simply for using cryptocurrency (AInvest). In such environments, a cross-border payment of compensation could potentially violate local criminal laws, trigger judicial assistance, and even lead to "cross-border offenses."

1.2 Not Worth It

No matter how cold and hard the numbers are, they cannot escape arithmetic: the claims that the Recovery Trust can smoothly distribute amount to about 95%, with only 5% of the claims listed in the "disputed pool" (technext24.com). If time and resources are spent on this 5%, not only will there be legal fees, but it may also slow down the repayment speed for creditors who have already been approved. This is equivalent to "deducting" a certain proportion of the distribution from all creditors' interests—no one wants to bear this "time tax."

Under the U.S. Chapter 11 bankruptcy framework, the trustee is bound by the "Prudent Person Rule," meaning they can only undertake actions within a "reasonably prudent" range, thus prioritizing the interests of the majority of creditors is very reasonable. The motion has designed three "insurance gates":

"Acceptable opinion" from local lawyers;

A 45-day objection window;

Final determination by the court on whether the "restricted designation" is reasonable.

This arrangement, on one hand, demonstrates respect for creditors' procedural rights, and on the other hand, provides systematic operability, allowing the judge to "preserve first, then assess," while also giving creditors ample opportunity to provide compliance evidence.

1.3 Summary

From the perspective of the FTX Recovery Trust, this motion is not an arbitrary wall but a serious "risk pricing": they attempt to balance compliance and compensation obligations within a controllable range, categorizing regions that could lead to criminal liability and significant delays.

However, you need to note that this motion, while not taking substantive action, merely sets up a procedure—the Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures. But the ultimate result of such a procedure is that creditors from the 49 listed countries and regions will end up receiving not a single cent.

2. How does the Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures actually work? — A close look at the "mechanisms" in each barrier

This fifteen-page motion document reads like a maze filled with traps. Each procedural design appears reasonable and compliant, yet could inadvertently push a legitimate creditor into the abyss of "automatic forfeiture."

2.1 First Barrier: Legal Opinion

Once the procedure is initiated, the Recovery Trust will hire "a qualified lawyer" in each country or region on the list to provide a legal opinion, determining whether the payment conflicts with local laws. The motion clearly states: only if the lawyer "unconditionally and without exception" confirms the legality of the payment can the creditors from that jurisdiction unlock their eligibility for compensation.

However, the problem lies precisely in those six words—"unconditionally and without exception." In many countries where digital asset policies are vague and laws are not yet clear, which lawyer would dare to endorse an unknown position? Not giving a qualified opinion could jeopardize their professional license; giving a qualified opinion would automatically be deemed "unqualified" by the Recovery Trust. The design of this barrier effectively turns "presumed legal" into "presumed illegal."

Thus, a common outcome of this compliance test is receiving a carefully worded but heavily qualified "unacceptable opinion," and the process then moves to the next stage.

2.2 Second Barrier: 45-Day Objection Window

When a country receives an "unacceptable opinion," the Recovery Trust will send a Restricted Jurisdiction Notice to the relevant creditors, notifying them that their claims may be forfeited. At this point, you only have 45 days to submit an objection—and you must also submit a declaration waiving additional procedural notifications and accepting the exclusive jurisdiction of the Delaware Bankruptcy Court.

On the surface, this seems like a reasonable opportunity for relief; but in reality, it sets up two "invisible thresholds":

The first is the delivery issue. Many creditors registered with FTX using temporary email addresses or overseas accounts, and the emails may have already sunk without a trace. If you do not notice this "fate-determining notice" within 45 days, the system will automatically consider it "no objection"—the door is closed.

The second is the legal cost. Within just a month and a half, you not only need to find a lawyer familiar with local crypto laws, but you also have to pay for their preparation of a positive legal opinion. This could mean spending thousands to tens of thousands of dollars in many countries. For small creditors with already low claim amounts, this is almost equivalent to "buying a redemption ticket with compensation money."

2.3 Third Barrier: Judge's Ruling

If no one raises an objection, or if the objection fails to meet the standards, the Recovery Trust will submit a brief motion to the bankruptcy court, formally applying to designate that country or region as a Restricted Foreign Jurisdiction. This step is unlikely to be rejected, as U.S. courts tend to "respect the trustee's prudent obligations" either intentionally or unintentionally.

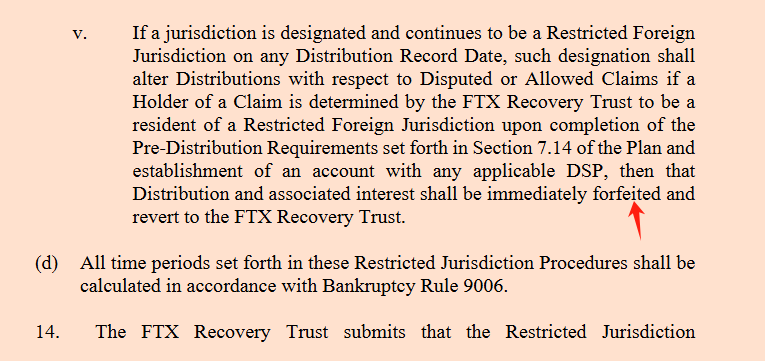

Thus, with a signature, starting from the next Distribution Record Date—even if you have already completed the claim declaration, even if the system previously showed you as an "Allowed Claimant," your claim will quietly change in the backend status bar to: FORFEITED.

The motion states clearly: "Once the Court enters such an order, all affected claims shall be deemed automatically disallowed and expunged as of the next Distribution Record Date."

2.4 Summary: A seemingly reasonable procedure, but layers of obstacles

On the surface, this motion is merely a technical arrangement for risk management—lawyer opinions, objection windows, court rulings, each link appears legitimate, compliant, and even reaches the extreme of "procedural justice."

But when we break it down step by step, we find that this process resembles a cleverly woven "legal trap": each step seems to offer you an opportunity, but in reality, it is a slow countdown to "automatic forfeiture."

3. Why is the "Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures" a "legal" forfeiture process?

To understand this step, one must translate the "procedural language" in the motion into "asset fate language." On paper, it never explicitly states "forfeiture"; however, when you piece together the entire process, you will find that everything it does is aimed at legally, quietly, and irreversibly reclaiming the rightful distributions of creditors from certain regions back into the recovery trust pool.

3.1 Triggering the Procedure = Transitioning from "Payable" to "Disputed Pool"

As long as a jurisdiction fails to obtain a local lawyer's unconditional and unqualified legal opinion on payment, the recovery trust can mark all claims from that area as "Disputed Claims." This is clearly stated in the motion text: upon receiving an "Unacceptable Opinion," the trust "is authorized to treat claims from these jurisdictions as disputed claims until the status is resolved" (CryptoSlate).

In other words, you were originally an "Allowed Claimant," but due to the legal ambiguity in your country, you are downgraded with a single click; the system sends you to the "waiting room," and the likely outcome of that wait is not receiving funds, but rather disappearing.

3.2 Notification + 45 Days of Silence = "Presumed Waiver"

Next is the "45-day objection window" we just dissected. The motion authorizes the trust to send a Restricted Jurisdiction Notice to the last address/email on file, which is deemed to fulfill the "commercially reasonable delivery obligation" (CryptoSlate).

The truly brutal logic is: the procedure assumes you can see the email; if you don't, it's your own problem. If you fail to object within the deadline, it equates to your presumed agreement to be excluded from compensation. Cointelegraph pointed out this key point: the trust seeks court approval to "suspend payments to 49 potential restricted jurisdictions" and warns creditors that failure to act will result in the loss of distribution eligibility (Cointelegraph, Cointelegraph).

3.3 Judge's Signature = Local Legal Shield, Global Forfeiture Gate

Once the objection period is over, the recovery trust will go to court to formally request that the jurisdiction be designated as a Restricted Foreign Jurisdiction. Once the ruling is established, the motion's Section 6 states harshly: from the next Distribution Record Date, the relevant claims from that jurisdiction "shall automatically be disallowed and expunged," and the corresponding amounts and interest "revert to the FTX Recovery Trust."

This is the key action of "legal" forfeiture—not a direct seizure, but through a judicial order, legally erasing your claim eligibility before the record date, and then rightfully transferring that money back to the trust pool.

CryptoSlate summarized this in simple terms: claims that fail to successfully object within the deadline or whose objections fail will see their frozen amounts and accumulated earnings "flow back to the estate" (CryptoSlate).

3.4 "Prudent Duty" as the Shield of the Procedure—Also the Knife of Passive Disqualification for Creditors

Why would the court agree? Because the motion simultaneously invokes Sections 105(a) and 1142(b) of the Bankruptcy Code, along with Bankruptcy Rule 3020(d), and cites Confirmation Order Section 135: the court may issue any order "necessary or appropriate" for executing the plan.

Within this framework, the trust claims it is merely fulfilling its prudent duty: avoiding random payments in restricted areas, preventing directors and officers from stepping into criminal liability, and avoiding wasting assets on foreign compliance (motion preamble + Sections 17, 20; Cointelegraph reports also cite "fines, personal criminal liability, and imprisonment risks") (Cointelegraph).

Do not forget the real data: the 49 jurisdictions on the watchlist account for only about 5% of the total payable claims, yet they could delay the payments for the remaining approximately 95% of creditors; among them, 82% of the affected value is concentrated in China, which is the single largest source of uncertainty (Cointelegraph, CryptoSlate).

From the judge's perspective, supporting the trust's "lock first, review later" approach seems to protect the majority—but the actual effect is to place a minority on a procedural slope, and once no one brakes in time, they directly slide into the forfeiture pool.

3.5 The Global Regulatory Paradox of "Can Only Do, Cannot Say"

The examples provided in the motion are not arbitrary: a 17-year-old in Tunisia was arrested for an online crypto transaction, prompting the finance minister to publicly consider "decriminalization"; this indicates that in some countries, "the public is doing it, but the authorities dare not say it is legal" (CoinDesk).

Looking at the Macao Monetary Authority, which warned local banks as early as 2017 that "they must not directly or indirectly provide financial services for token-related activities," it shows that "platforms making payments to residents" could be equated with illegal financial services (Macao Special Administrative Region Government Portal).

On the Chinese side, the central bank's announcement in 2021, in conjunction with multiple ministries, clearly stated that virtual currency-related business activities are illegal; providing services to domestic investors from overseas exchanges is prohibited. Reuters reported the same year emphasizing that financial and payment institutions must not provide crypto-related services (Reuters, Reuters).

Imagine being in such a jurisdiction where "you can use it, but cannot say it is legal," and asking a local lawyer to sign off saying "completely legal, without reservation"—this almost requires them to gamble their license on the future. The rational choice for the lawyer is to provide a conservative opinion; a conservative opinion in the procedure = unqualified; unqualified = entering the forfeiture track. By this point, the design of the process completes a logical loop.

3.6 Summary: So, why does it resemble forfeiture?

Because it is a structure of first suspending, then proving, then ruling, and finally reclaiming:

Default risk;

Burden of proof on creditors;

No proof → loss of rights;

Funds revert to the pool, legally redistributed.

The "Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures" that the motion seeks to pass does not explicitly say "take your money," but it paves all paths for your money to be transferred in the background through "lack of evidence," "expiration," and "ruling." Formally legal, but substantively depriving—this is "legal forfeiture."

Of course, not all crows are black. FTX is not the first to compensate creditors after bankruptcy. By examining other compensation cases, you will see how other custodians protect creditors, revealing how unscrupulous the FTX Recovery Trust is.

4. Three Cases That Show How Unethical the "FTX Recovery Trust" Is?

Certainly, the "Restricted Jurisdictions Procedures" proposed by the FTX Trust is not as reasonable as it appears on the surface. To make this process seem "compliant," it must hide a prerequisite assumption: that globally, this uniform ban and automatic forfeiture treatment of "gray area" countries is accepted and even common practice.

But the reality is quite the opposite.

Whether it is the previously larger and more complex Mt. Gox bankruptcy case or the Celsius and Voyager cases, which are part of the same wave of crypto exchange bankruptcies as FTX, none of these cases adopted such an aggressive one-size-fits-all approach. The principle they followed is: even if compliance is complex, every effort must be made to ensure the safety of creditors' assets; even if compensation is slow, the essence of "forfeiture" cannot be smuggled under the guise of "procedure."

Let us now take a closer look at these three landmark cases to see how other projects have chosen to stand by creditors in a truly complex global legal environment—rather than using compliance as a shield and turning procedures into scissors like the FTX Trust. Chinese creditors should pay special attention to the last case of OKEx, which should provide some insights.

4.1 Mt. Gox: A Decade-Long Restructuring, but "No Payment Means Forfeiture" Has Never Become the Default Option

The bankruptcy restructuring of Japan's Mt. Gox took a decade of detours: from the 2014 hacking incident that resulted in the loss of approximately 850,000 BTC, to the gradual recovery of assets and entry into civil rehabilitation proceedings, and then starting in 2024, distributing BTC, BCH, and other assets through multiple trustee platforms in batches.

Despite the varying global regulatory standards and creditors spread across the world (approximately 127,000), the Japanese restructuring trustee, Nobuaki Kobayashi, adopted a "parallel track" model—allowing creditors to choose their preferred method of receiving payments from several cooperating channels: cryptocurrency (through virtual asset service providers like Kraken, Bitstamp, Bitbank, SBI VC Trade), or bank wire transfers/remittance services, as well as various options for one-time or phased combinations.

Official announcements repeatedly reminded creditors that failure to timely complete "method selection + payment information registration" would delay or even prevent payment—but this was "you won't get money if you don't register," not "your country is non-compliant, so the money goes back to the pool" (Cointelegraph, CoinDesk).

More critically: even if a particular cooperating channel could not serve residents of specific countries due to its own regulatory commitments (Bitstamp's Mt. Gox support announcement explicitly listed a long list of restricted regions, including China), the trustee still retained other viable payment channels (such as bank transfers and other trustee exchanges) and did not convert these regulatory obstacles into "claim extinguishment."

This stands in stark contrast to the FTX motion's "lack of unqualified opinion → 45 days of silence → judge's ruling → claims flowing back to the trust" one-way slope (CoinDesk, The Bitstamp Blog by Robinhood).

Looking at the execution level: Kraken announced the completion of its batch distribution of Mt. Gox BTC/BCH; Bitstamp subsequently initiated disbursements; despite market concerns about massive selling pressure, there was no large-scale abandonment of claims due to "inability to collect."

This indicates that even in a complex cross-border and cross-regulatory environment, conflicts can be reduced through "multiple channels + longer preparation periods + alternative options" without directly transferring risks into creditors' "procedural forfeiture" (Cointelegraph, CoinDesk).

4.2 Celsius: Covering 165+ Countries, 250,000+ Creditors, Complex Distribution Can Still Be Achieved

Celsius faced a crisis in 2022 and entered the bankruptcy court proceedings in the Southern District of New York; it officially exited bankruptcy protection and initiated the distribution process on January 31, 2024. The total plan amounts to over $3 billion (crypto assets + fiat), and it will distribute shares of the restructured Bitcoin mining company Ionic Digital to creditors; this restructuring plan received 98% support from account holders in the voting process (Business Communications).

Execution progress: As of the first status report in August 2024, the bankruptcy plan administrator has paid $2.53 billion to over 251,000 creditors (valued as of January 16, 2024, including liquid crypto and cash), covering about two-thirds of all eligible creditors and 93% of the total value.

The broader context is that Celsius's distribution system targets approximately 375,000 creditors across more than 165 countries; its own complexity, described in official documents as "perhaps one of the most complex and ambitious distribution processes in Chapter 11 case history," stems from being "not fully compliant before the incident and facing regulatory scrutiny in multiple countries" (CoinDesk).

Celsius's operational logic is to "manage to get the money into your hands," rather than "give up if the path is unclear." The official/court-appointed agent (Stretto) continuously maintains a complete online support ticket system: What to do if the original registered email is lost? How to change the payment method? Multilingual guidance? These are all listed in the FAQ and support documents, clearly stating "incomplete information -> delay," rather than automatic forfeiture (Celsius Distributions, CoinDesk).

The distribution structure is not simply "all crypto or all cash," but adjusts based on the asset pool and regulatory feedback—this includes converting altcoins that cannot be returned in their original form into BTC/ETH to simplify global distribution (an additional nearly $250 million in distributable crypto assets was added to the plan), along with Ionic Digital shares; this kind of flexible combination aims to maximize recovery under different jurisdictional restrictions, rather than using uncertainty to reduce claims (Business Communications, CoinDesk).

4.3 OKEx Withdrawal Suspension Incident: "Freeze First, Fully Open Later" in a Regulatory Gray Area

In October 2020, OKEx (now OKX) suddenly announced a suspension of all crypto asset withdrawals, citing that "a private key holder is cooperating with law enforcement and is temporarily unreachable"; this incident occurred against the backdrop of high-pressure regulation in China and exchanges "going overseas," causing panic among users globally, especially in China (Reuters, Nasdaq).

The platform's freeze lasted about five weeks. During this time, the market was concerned about funding chains and law enforcement risks, but OKEx repeatedly emphasized the safety of user assets and maintained trading and other functions as usual. On November 20, they announced that the issue had been resolved and that all asset withdrawals would be fully restored by November 27, along with compensation/loyalty rewards to appease customers; the announcement specifically reiterated that "we have always maintained 100% reserves, and unlimited withdrawals will be allowed after unfreezing" (fintechfutures.com, Nasdaq).

Multiple reports and subsequent information indicate that the investigation stemmed from the context of Chinese law enforcement; however, OKEx's choice was "short-term freeze for compliance checks, allowing users to withdraw after recovery," rather than long-term detention or even forfeiture under the guise of regulation.

Even though the Chinese market is referred to as a "regulatory gray area" where "what can be done may not be openly stated," the platform still sought to retain customers through the restoration of withdrawals and compensation activities—this stands in stark contrast to the FTX Recovery Trust, which directly pushed claims into "unprovable = automatically void" paths in the face of regulatory uncertainty (Nasdaq, fintechfutures.com).

4.4 Summary: How Other Cases Navigate the Minefield, While FTX Turns the Minefield into a "Waiver Zone"

When you put these three cases together, you will find that the real distinction lies not in how strict the regulations are, but in whether the administrators choose to "solve the problem" or "make the problem your fault":

Mt. Gox: Fragmented regulation → multiple payment channels + long registration periods; limited channels ≠ claim extinguishment (Cointelegraph, CoinDesk).

Celsius: Complex KYC across 165 countries → online support, flexible asset combinations, ongoing information supplementation; global distribution still advancing over $2.5 billion (CoinDesk, Celsius Distributions).

OKEx: Impacted by Chinese law enforcement → short-term safety freeze, followed by full opening of withdrawals and user compensation; did not transfer gray area regulation into permanent losses for customers (fintechfutures.com, Nasdaq).

In contrast, the FTX Recovery Trust requires "unconditional, no exceptions" legal opinions—something that is rarely achievable in reality; a 45-day silence presumes waiver—many small cross-border creditors find it difficult to respond; a judge's signature leads to "automatic expunge" of claims—funds flow back to the trust's total pool for redistribution. The procedure appears compliant on the surface, but in essence, it is closer to "default forfeiture under a legal guise" (Cointelegraph, DL News, BitDegree).

5. The Dual-Line Battle Map for Chinese Creditors

FTX's "Restricted Jurisdiction" motion is like a quietly descending net, covering creditors in 49 countries or regions worldwide. At this moment, those of us caught in it have only two paths to take: one is to prevent this net from officially landing, and the other is to actively counterattack once it does land.

Rather than a strategy, this is a survival instinct. We cannot wait for others to decide our fate.

5.1 First Line: Counter the Motion Before the Trap is Completed

From a procedural standpoint, the motion submitted by the recovery trust will hold a hearing on July 22, 2025, at 9:30 AM (Eastern Time). Although the deadline for submitting official objections has passed on July 15, it is still possible to claim "delivery defects" or "delayed awareness" to apply for a supplementary submission. Time is short, but we still have a chance to fight.

The key to countering this motion lies in one point: significant modification of the plan.

The motion has made substantial changes to the original confirmation plan—what was initially agreed upon as "compensation available after completing KYC" now includes an additional requirement of "an unconditional confirmation of compliance by a lawyer," which is equivalent to changing the rules on the fly.

In addition to pointing out the problems, we must also propose solutions. For example, Mt. Gox provided alternative payment methods through multiple channels—some countries may not be convenient for direct remittance, so they switched to fiat or offline exchanges; Celsius also allowed creditors to choose different combinations of currencies for receipt. We can advocate for a similar mechanism, rather than "no payment means forfeiture."

If we can push the judge to include a clause in the approval of the motion stating that even if payments are temporarily suspended, the funds must be held in escrow and not returned to the trust pool, then even if we cannot receive compensation immediately, our claims will at least still exist.

This is our first line of defense, a "defensive" sprint. Winning would be best, but even if we cannot completely block it, we have gained valuable preparation time for the second line.

Fortunately, Will has already submitted an objection before July 15.

5.2 Second Line: Take the Initiative, Make "Forfeiture" Costly for Them

If the hearing on July 22 ultimately results in the motion being approved, the recovery trust will immediately initiate the next phase of the "restricted procedure." The 45-day objection window, lawyer opinion gate, and forfeiture clauses will all be in place.

In such a situation, relying solely on individual objections is not only costly but also has a high failure rate. The truly effective approach is to initiate a proactive class action lawsuit against the FTX Recovery Trust for breach of contract and tort, bringing them to the defendant's seat.

This is not an emotional outburst, but a counterattack supported by ample legal grounds.

First is the breach of the confirmation plan. The "Reorganization Confirmation Order" passed by the court on October 8, 2024, clearly states that all creditors who complete KYC are entitled to distribution. However, the current motion attempts to terminate this distribution obligation on the grounds of "legal opinion not meeting standards," without following the amendment procedure stipulated in Section 1127 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. This itself constitutes an illegal modification of the plan.

Second is the violation of fiduciary duty. The essence of the recovery trust is to maximize recovery for all creditors, not just serve creditors from "a few countries." It should remain neutral and not set procedural traps that automatically void claims from certain countries.

Third is civil tort. If the motion passes and a creditor from a certain country is marked as "FORFEITED" (i.e., deemed waived) due to "opinion not meeting standards," that money will directly "flow back" to the trust for its own use. This is not only blatant unjust enrichment but may also constitute "conversion"—an act of illegally possessing someone else's property.

5.2.1 Jurisdiction and Practical Operation: Not Just Words, But Action

Some may ask: Can we sue them in U.S. courts? The answer is affirmative.

The main battlefield remains in the Delaware bankruptcy court, but we can also choose to file independent lawsuits in New York or other courts with jurisdiction, citing "tort" or "breach of contract" to bypass various restrictions within the bankruptcy law framework.

Under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a class action can be formed with just five or more creditors to represent all creditors harmed under similar circumstances. This means—we do not need everyone to participate personally; as long as we gather a representative "plaintiff group," the lawsuit can be initiated.

5.2.2 Freezing Trust Assets: Letting Them Know We Are No Longer Passive

This lawsuit is not just a "theoretical victory"; we can also employ some effective tactics during the process—such as applying to the court for "pre-judgment asset attachment."

This is a legal measure commonly used in cross-border financial disputes; once approved by the court, we can temporarily freeze FTX Recovery Trust's U.S. bank accounts, third-party recovery proceeds, and other assets before the litigation is heard, preventing them from continuing to make payments to "compliant countries."

Similar actions were used in the Wirecard (German payment giant) case, freezing assets in London to ensure smooth progress in compensation negotiations.

This is not to prevent everyone from receiving compensation, but to signal to the trust: if they choose to favor certain parties, we also have means to make them bear the costs.

5.2.3 Public Opinion and Diplomacy: Restoring Fairness and Justice to the "Rules Game"

Currently, Reuters and Bloomberg have explicitly mentioned in their reports on the motion that "Chinese creditors' $380 million may be forfeited," which has garnered global attention for us. Next, we can amplify our voice through more influential media such as the BBC and AFP, emphasizing that this is not a Sino-American dispute, but a global issue of procedural discrimination.

At the same time, creditors from affected countries can submit opinion letters to the U.S. Department of the Treasury (OFAC) or the U.S. Trustee through their own financial regulatory authorities and diplomatic missions. Such "national-level interventions" are not uncommon in history— for example, in the TelexFree phone card fraud case, it was the intervention of the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that ultimately led to the U.S. agreeing to a joint compensation agreement.

5.3 Immediate Action: From Groups to Battalions

Once the motion is approved, we must immediately establish the "FTX Restricted Jurisdictions Creditors Committee" and release a multilingual online recruitment form.

Select a U.S. bankruptcy law firm with class action experience;

Simultaneously initiate breach of contract and tort lawsuits in Delaware and New York;

Apply to the court for a temporary restraining order (TRO) to prevent "restricted funds" from being redistributed to compliant country creditors.

At the same time, it is recommended that the current main group advocating for rights initiate a fundraising campaign to ensure the smooth progress of the litigation. I, along with the "Airdrop Reference" project, will each donate 1,000 USDC.

5.4 China's Key Role: Not for Itself, but for Everyone

We must be acutely aware that Chinese creditors indeed face the highest barriers. Lawyers are reluctant to issue "unqualified opinions," and regulatory policies are highly uncertain. This is unfortunate, but it also means that once Chinese creditors secure "alternative pathways" or "delayed escrow" arrangements, the other 48 countries will naturally benefit.

We are not fighting for privileges for one country; we are opening up a potential new rule for the world.

Because once the $380 million "ice block" from China is broken, the other 1% to 2% of countries that are passively sidelined will lose their justification for being ignored by the trust.

From a cost perspective, this is even more advantageous for the trust: rather than risk being sued, freezing assets, and facing media attacks, it is better to reach an agreement for less money.

5.5 Final Reminder: Do Not Let Procedure Obscure the Face of Justice

The FTX Recovery Trust is not an organization without risk control logic; it can even be said to be a model of "acting in accordance with the law"—but that is precisely the most frightening aspect.

Because it is these seemingly perfect procedures that quietly turn our claims into objects of "systemic forfeiture." Once the process begins to operate, your silence equates to abandonment.

Countering the motion is a sprint against time; while the litigation counterattack is a marathon that requires endurance and wisdom. But as long as we take action and unite, we can make the cost of this "automatic forfeiture" game far exceed their budget.

This is a "Robin Hood operation" for Chinese creditors.

Conclusion | Justice Cannot Be "Reversed" by Procedure

The "Restricted Jurisdiction Procedure" of the FTX Recovery Trust, while superficially cloaked in compliance, is in fact a structural exclusion mechanism: in the reality of global asset flows and local legal disconnection, it treats procedure as a barrier rather than a channel.

If this model of "no lawyer opinion = automatic waiver" is deemed legal in Delaware, it will no longer be just a liquidation experiment, but a template for the systematic deprivation of cross-border creditors in future crypto bankruptcies.

This is not compliance; this is "assuming you are illegal"; it is not a legal procedure, but "legalized forfeiture."

Do not forget that all of this is built on the fog of global regulation. For example: In a joint regulatory notice in 2021, while China prohibited financial institutions from participating in virtual currency business, it did not explicitly prohibit individuals from holding or trading; Macau warns of token trading risks but imposes no criminal penalties; Tunisia has some enforcement cases but lacks a unified judicial interpretation.

For these countries, "available but unspoken" has almost become a reality.

In this gray area, seeking a "no exceptions, no conditions" lawyer opinion is essentially a luxury.

Procedures were originally meant to be the sword of law, but now they have become a veil of shame. When procedures become filters that exclude the vulnerable from justice, they cease to be rules and become tools. Today, it is a minority of people in 49 countries who are restricted; tomorrow, it could be any asset in your or my hands.

I have outlined two paths of resistance:

Line A: Counter the motion, demanding escrow or alternative compensation;

Line B: Immediately counter-sue after the motion passes, freezing trust assets and forcing renegotiation.

This is not an emotional confrontation, but a counterattack within the system. This is also a "moment of awakening" for cross-border creditors: If we do not speak up now, this template will be repeatedly replicated in the future; but if we stand up now, it will become the first case of anti-procedural discrimination written by global creditors.

Because:

Procedures are meant to protect justice and should not become tools that filter out justice.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。