Written by: Daniel Barabander, General Counsel and Investment Partner at Variant

Translation: @Golden Finance xz

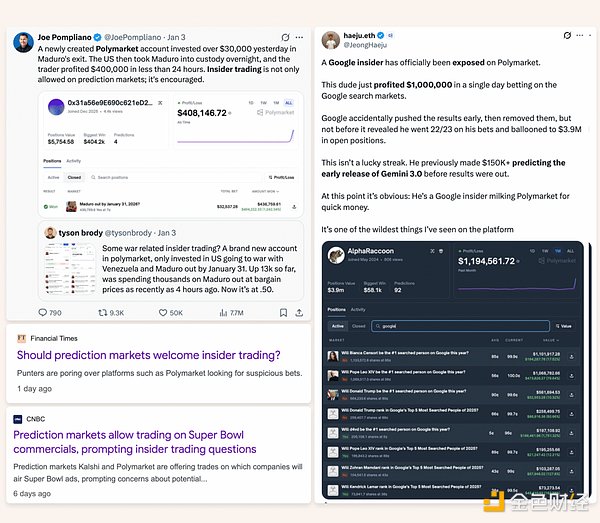

Insider trading in prediction markets has recently become a hot topic of discussion.

Many founders have noticed that before significant events occur, there are always unknown wallet addresses suddenly making trades, leading them to question: Is there illegal activity happening? To answer this question, we need to take a step back to understand the actual mechanisms of insider trading—which most people are not familiar with.

If you consult most lawyers about insider trading, you will hear a lot of obscure legal terminology. They will mention "fiduciary duty," "classical theory," "misappropriation theory," "tipper," "tippee," "insiders," "outsiders," and so on. When trying to apply these concepts to emerging fields like prediction markets, even they may become confused.

(This is not legal advice; please consult a professional lawyer for specific issues.) Here, I would like to provide a simplified analytical framework to explain my general understanding of insider trading and how I believe it should apply to prediction markets.

Insider Trading = A Form of Fraud

The first thing you need to understand about insider trading is that the law views it as a form of fraud. Like all forms of fraud, insider trading involves deception carried out for personal gain. This deception typically arises from a breach of an explicit or implicit promise regarding the "use of material nonpublic information." There is no standalone "insider trading law"; there are only anti-fraud rules that apply to insider trading. The main distinction between insider trading fraud and the fraud commonly understood is that the former's promises are often more obscure, making them easier to violate.

The typical pattern of insider trading is: an employee violates their commitment to their employer by trading stocks using significant nonpublic information about the company. Whether you agree or not, when you work for a company, you have implicitly promised (as established by law) to act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders. This promise is likely explicitly stated in the employee handbook you agreed to follow upon joining. When an employee trades company stock using significant nonpublic information, the counterparty shareholders are at an informational disadvantage; trading on this asymmetry constitutes a fraudulent breach of the commitment to the shareholders.

What I find people often overlook is that this is just one manifestation of insider trading. Anyone who fraudulently violates an explicit or implicit promise in a trade may constitute insider trading.

For example: suppose an employee learns that the company is involved in a merger transaction. The employee knows that the typical insider trading scenario is not permissible, so they attempt to "cleverly" use that significant nonpublic information to buy stock in the company's largest competitor, expecting the competitor's stock price to soar after the news is announced. Although the employee has no implicit loyalty obligation to the competitor's shareholders, this action may still constitute insider trading. The reason is that the employee has committed, through company policy, confidentiality agreements, or implicit loyalty obligations, to use confidential information only for legitimate business purposes. Using that information for personal trading in a competitor's stock clearly violates this commitment. Therefore, the employee can be deemed to have fraudulently breached their commitment, thus engaging in insider trading.

Commitment is Key

Commitment is at the core of the issue. Suppose someone overhears two investment bankers at a neighboring table loudly discussing a pending merger transaction during lunch. After recognizing the target company, the person leaves the restaurant and trades the company's stock before the announcement. Although this information clearly constitutes significant nonpublic information, this action typically does not constitute insider trading. This is because the trader has made no explicit or implicit confidentiality commitment to the investment bankers and has no implicit obligation to the company and its shareholders. The investment bankers may have violated their own obligations by discussing it carelessly in public, but if the trader has not engaged in any fraudulent breach of duty, there is no fraud—thus, it does not constitute insider trading.

Anyone who fraudulently violates an explicit or implicit promise in a trade may constitute insider trading.

From the perspective of "fraudulent breach of commitment," we can correct a common misconception: insider trading is not limited to the securities field. On the contrary, similar issues may arise in commodity markets (including derivatives markets). For example, a derivatives trader at Cargill learns through work that the company will purchase a large quantity of wheat and then trades in the wheat futures market using a personal account ahead of time; this behavior may very well constitute insider trading. In this case, the trader has committed, through company policy, confidentiality agreements, or job responsibilities, to use confidential information only for Cargill's business purposes, and their personal trading constitutes a fraudulent breach of that commitment. Conversely, if the trader's responsibilities include trading on behalf of Cargill before executing the purchase, it would not constitute insider trading—despite acting based on significant nonpublic information (i.e., knowing the company's planned market transaction), it does not constitute a fraudulent breach of commitment: the trader has no implicit obligation to other futures traders, and trading on that information is precisely the job they are authorized to perform for their employer.

Applicable to Prediction Markets as Well

So what does this mean for prediction market traders? My core point may be disappointing due to its simplicity: the law itself has not changed. Fraud is fraud, and legal rules are flexible. The key question always remains: did the trader fraudulently violate a commitment through the trade?

Therefore, if a Tesla employee possesses fourth-quarter financial data and uses that information to trade in the prediction market for "Will Tesla's fourth-quarter performance exceed expectations?", it may very well constitute insider trading. The reason this behavior constitutes insider trading is either that the employee has violated a commitment to Tesla's shareholders or breached a confidentiality agreement or other agreement prohibiting the use of company confidential information for personal gain. But suppose the same employee instead trades in the prediction market for "Will the growth rate of electric vehicle charging demand in the next two years exceed gasoline demand?"—as long as they are using publicly available electric vehicle adoption data and industry expertise accumulated from years of working at Tesla (rather than Tesla's internal plans), it likely would not constitute insider trading, as they have not misused confidential information or violated a commitment.

However, prediction markets will push the law to its boundaries and test whether it can adapt or be breached. Traditional markets are usually tied to specific companies: the securities market is directly related to companies (like Tesla's fourth-quarter performance), while the commodity market is indirectly related (like Cargill's wheat purchases). This is crucial because companies are often the source of confidentiality commitments and commitments to use information solely for business purposes—these commitments (whether legally implied or explicitly agreed upon through confidentiality agreements, policies, etc.) form the basis of insider trading liability.

Prediction markets expand the range of trading subjects (making almost anything tradable), broadening the sources of valuable insider information, often involving scenarios where the existence of relevant commitments is extremely unclear. This is particularly pronounced in permissionless or opinion-based markets, which often lack any relevant company at all.

For example: suppose a high school has a prediction market for "Who will be crowned prom king?" Your friend is the most popular person in the class, and he privately informs you that he cannot attend the prom. If you trade based on that information, does it constitute insider trading? The legal question still hinges on whether you fraudulently violated a commitment, but in this context, any such commitment would need to be implicitly inferred from your relationship or the context of the information disclosure, rather than stemming from a clear obligation or formal agreement to a company. This makes the litigation determination of insider trading extremely difficult.

The legal boundaries will soon become very blurry.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。