Original Title: The Microstructure of Wealth Transfer in Prediction Markets

Original Author: Jonathan Becker

Original Compilation: SpecialistXBT, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: The author provides a detailed analysis of how the irrational preference of retail traders between "longshot" and "certain outcomes" contributes to the emergence of the "Optimism Tax." This is not only a hardcore analysis of market microstructure but also a cautionary guide that every participant in prediction markets should heed.

The following is the original content:

On the Las Vegas Strip, slot machines return about 93 cents for every dollar wagered. This is widely regarded as one of the worst odds in gambling. However, on the prediction market Kalshi, regulated by the CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission), traders have bet large sums on "longshot" contracts with historical returns as low as 43 cents per dollar. Thousands of participants willingly accept a much lower expected value than that of casino slot machines, just to place bets on their beliefs.

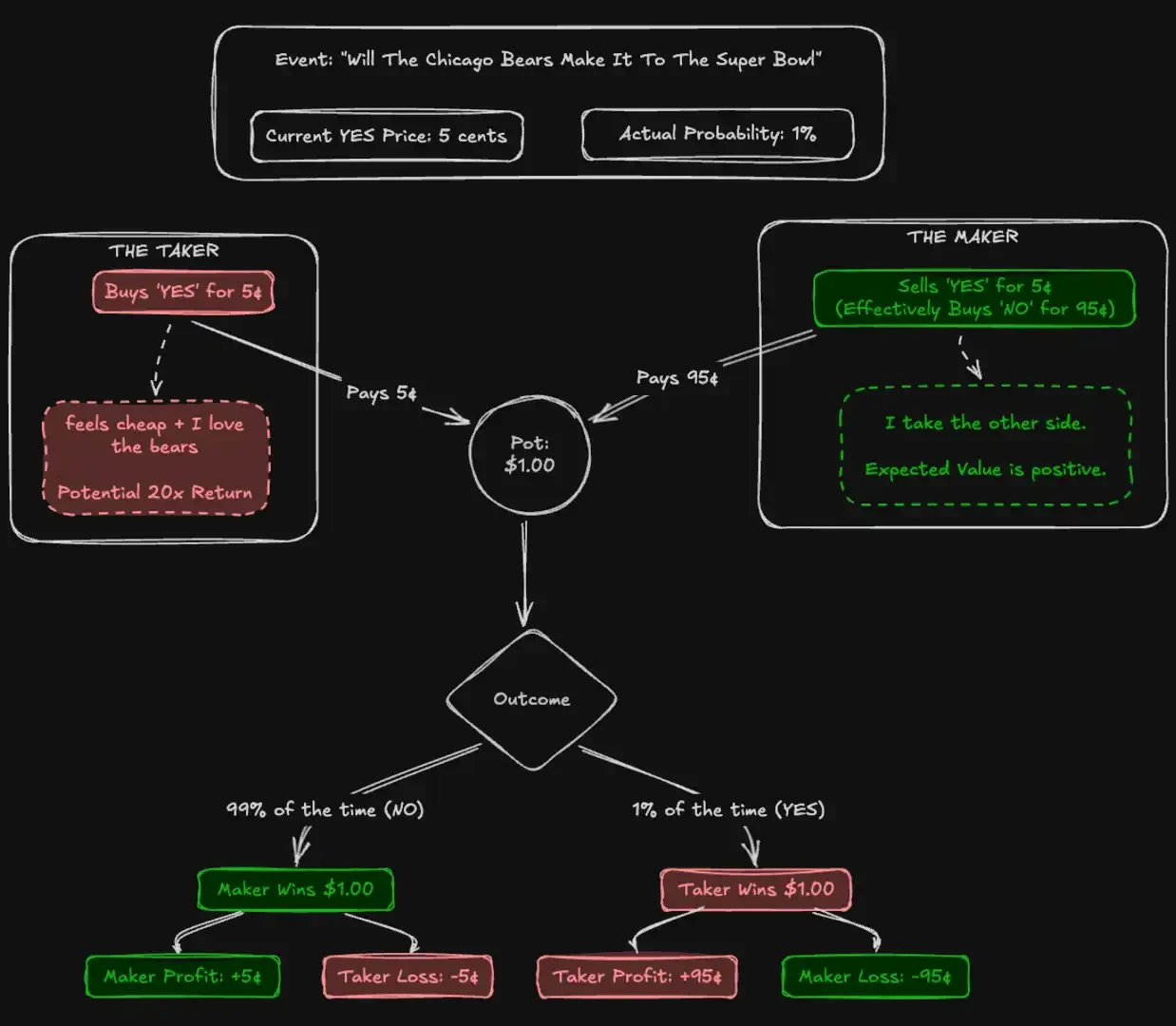

The Efficient Market Hypothesis posits that asset prices should perfectly aggregate all available information. Theoretically, prediction markets provide the purest test of this theory. Unlike stocks, the intrinsic value of prediction markets is unambiguous: a contract either pays $1 or it does not. A price of 5 cents should precisely imply a 5% probability.

To test this validity, we analyzed 72.1 million trades covering $18.26 billion in trading volume. Our findings indicate that the accuracy of the crowd relies less on rational actors and more on a mechanism of "harvesting errors." We recorded a systematic transfer of wealth: impulsive "Takers" pay a structural premium for affirmative "YES" outcomes, while "Makers" simply capture the "Optimism Tax" by selling contracts to this biased flow of funds. This effect is most pronounced in high-participation categories like sports and entertainment, while in low-participation categories like finance, the market approaches perfect efficiency.

Contributions of this Paper

This paper makes three contributions.

First, it confirms the existence of "longshot bias" on Kalshi and quantifies its magnitude at different price levels.

Second, it breaks down returns by market role, revealing a continuous transfer of wealth from Takers to Makers driven by asymmetric order flow.

Third, it identifies a "YES/NO asymmetry," where Takers disproportionately prefer affirmative bets on high-risk wagers (low probability prices), exacerbating their losses.

Prediction Markets and Kalshi

Prediction markets are exchanges where participants trade binary contracts on real-world outcomes. These contracts settle at either $1 or $0, with prices ranging from 1 to 99 cents, serving as proxies for probabilities. Unlike stock markets, prediction markets are strictly zero-sum games: every dollar of profit corresponds exactly to a dollar of loss.

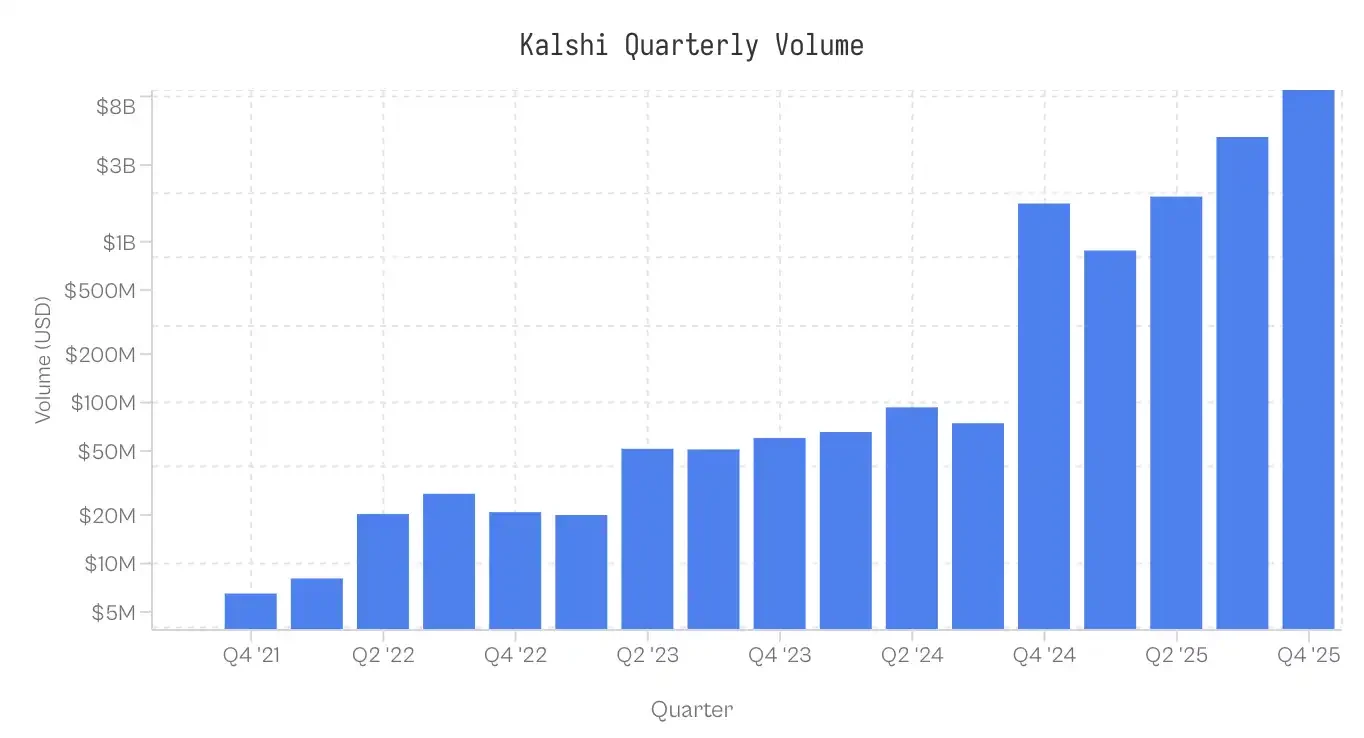

Launched in 2021, Kalshi is the first CFTC-regulated prediction market in the U.S. The platform initially focused on economic and weather data, remaining niche until before 2024. After legally overcoming the CFTC and gaining the right to list political contracts, the 2024 election cycle triggered explosive growth. The sports market introduced in 2025 currently dominates trading activity. The distribution of trading volume across categories is highly uneven: sports account for 72% of nominal trading volume, followed by politics (13%) and cryptocurrency (5%).

Note: Data collection was cut off on November 25, 2025, at 5:00 PM ET; data for Q4 2025 is incomplete.

Data and Methodology

The dataset includes 7.68 million markets and 72.1 million trades. Each trade records the execution price (1-99 cents), the Taker side (yes/no), the number of contracts, and a timestamp.

Role Assignment: Each trade identifies the liquidity consumer (Taker). Makers take the opposite position. If taker_side = yes and the price is 10 cents, it means the Taker buys YES at 10 cents; the Maker buys NO at 90 cents.

Cost Basis (Cb): To compare asymmetries between YES and NO contracts, we standardized all trades by risk capital. For a standard 5-cent YES trade, Cb=5. For a 5-cent NO trade, Cb=5. Unless otherwise specified, "price" mentioned in this paper refers to this cost basis.

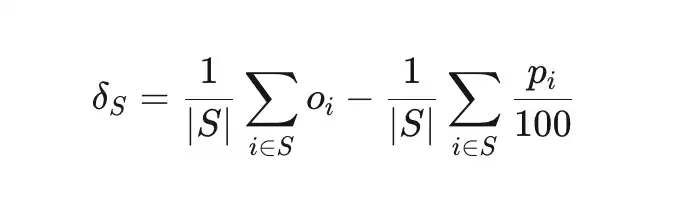

Mispricing (δS) measures the deviation between the actual win rate of a set of trades S and the implied probability.

Total Excess Return (ri) is the return relative to cost (before platform fees), where pi is the cent price, and oi∈{0,1} is the outcome.

Sample

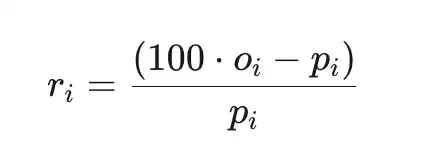

Calculations are based solely on settled markets. Markets that have been canceled, delisted, or remain open are excluded. Additionally, trades in markets with nominal trading volume below $100 are also excluded. The dataset remains robust across all price levels; even the least traded range (81-90 cents) contains 5.8 million trades.

Longshot Bias on Kalshi

Longshot Bias was first recorded by Griffith (1949) in horse racing and later formalized by Thaler & Ziemba (1988) in their analysis of pool betting markets. It describes the phenomenon where bettors tend to pay excessively high prices for low-probability outcomes. In an efficient market, a contract priced at p cents should have approximately a p% chance of winning. In markets with Longshot Bias, low-priced contracts have win rates below their implied probabilities, while high-priced contracts have win rates above their implied probabilities.

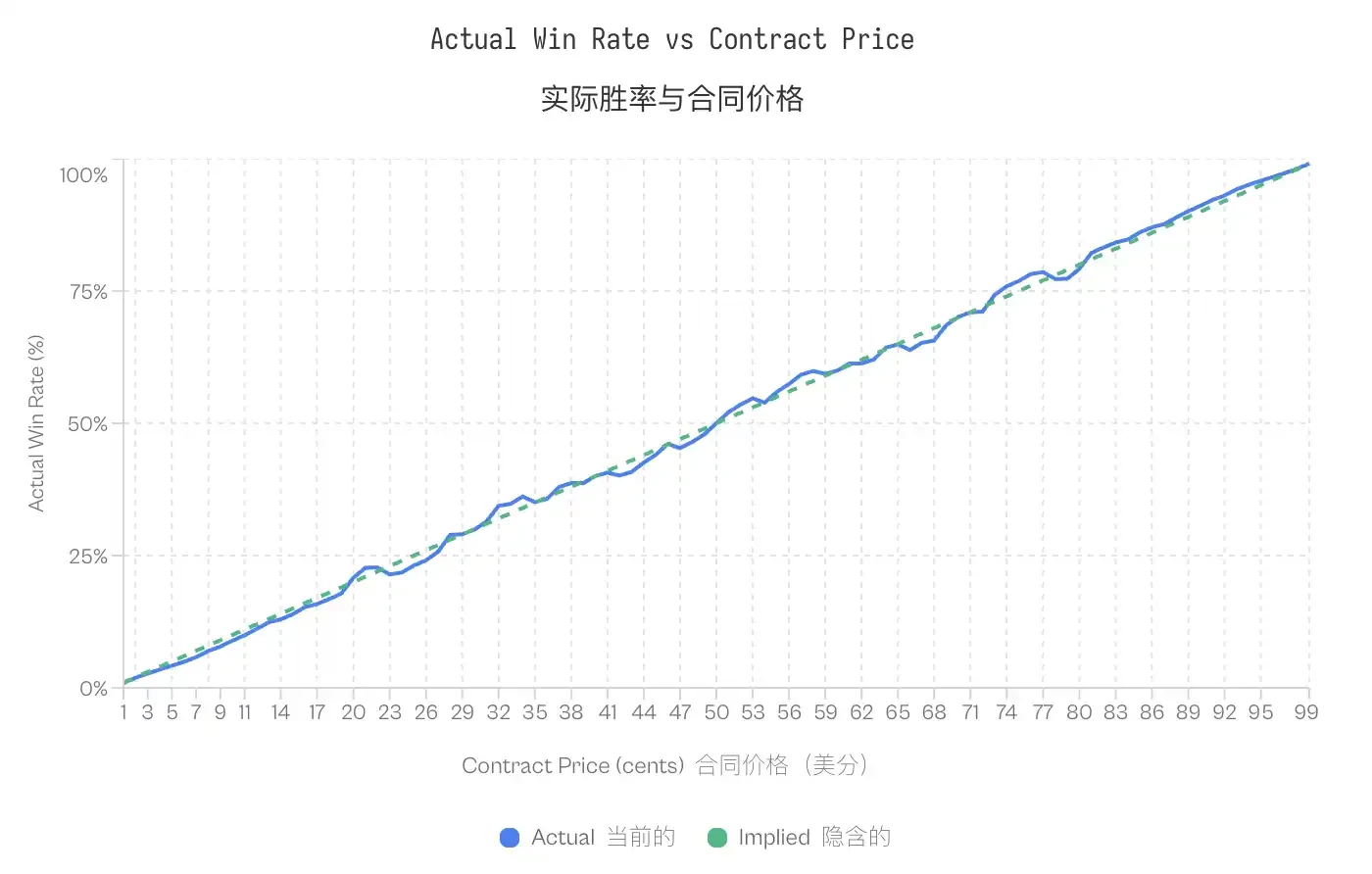

Data from Kalshi confirms this pattern. Contracts trading at 5 cents have only a 4.18% win rate, implying a -16.36% mispricing. In contrast, contracts priced at 95 cents have a win rate of 95.83%. This pattern is consistent: all contracts priced below 20 cents perform worse than their odds, while those above 80 cents perform better than their odds.

Note: Despite this bias, the calibration curve shows that prediction markets are actually quite effective and accurate, with slight exceptions at the tails (extremely low or high prices). The close alignment of implied probabilities with actual probabilities confirms that prediction markets are well-calibrated price discovery mechanisms.

Note: Despite this bias, the calibration curve shows that prediction markets are actually quite effective and accurate, with slight exceptions at the tails (extremely low or high prices). The close alignment of implied probabilities with actual probabilities confirms that prediction markets are well-calibrated price discovery mechanisms.

The existence of Longshot Bias raises a unique question in zero-sum markets: if some traders systematically pay excessively high prices, who captures the remaining value?

Wealth Transfer from Makers to Takers

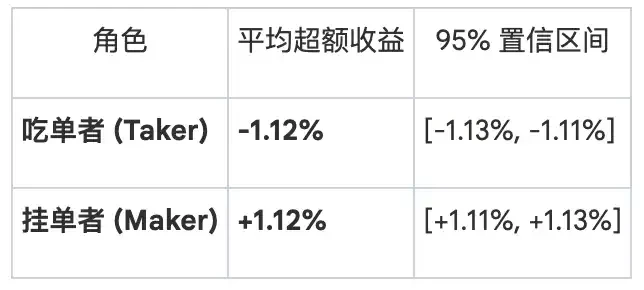

Breaking down returns by role, market microstructure defines two types of participants based on their interaction with the order book. Makers provide liquidity by placing limit orders that remain on the order book. Takers consume liquidity by executing trades against existing orders. Breaking down total returns by role reveals a clear asymmetry:

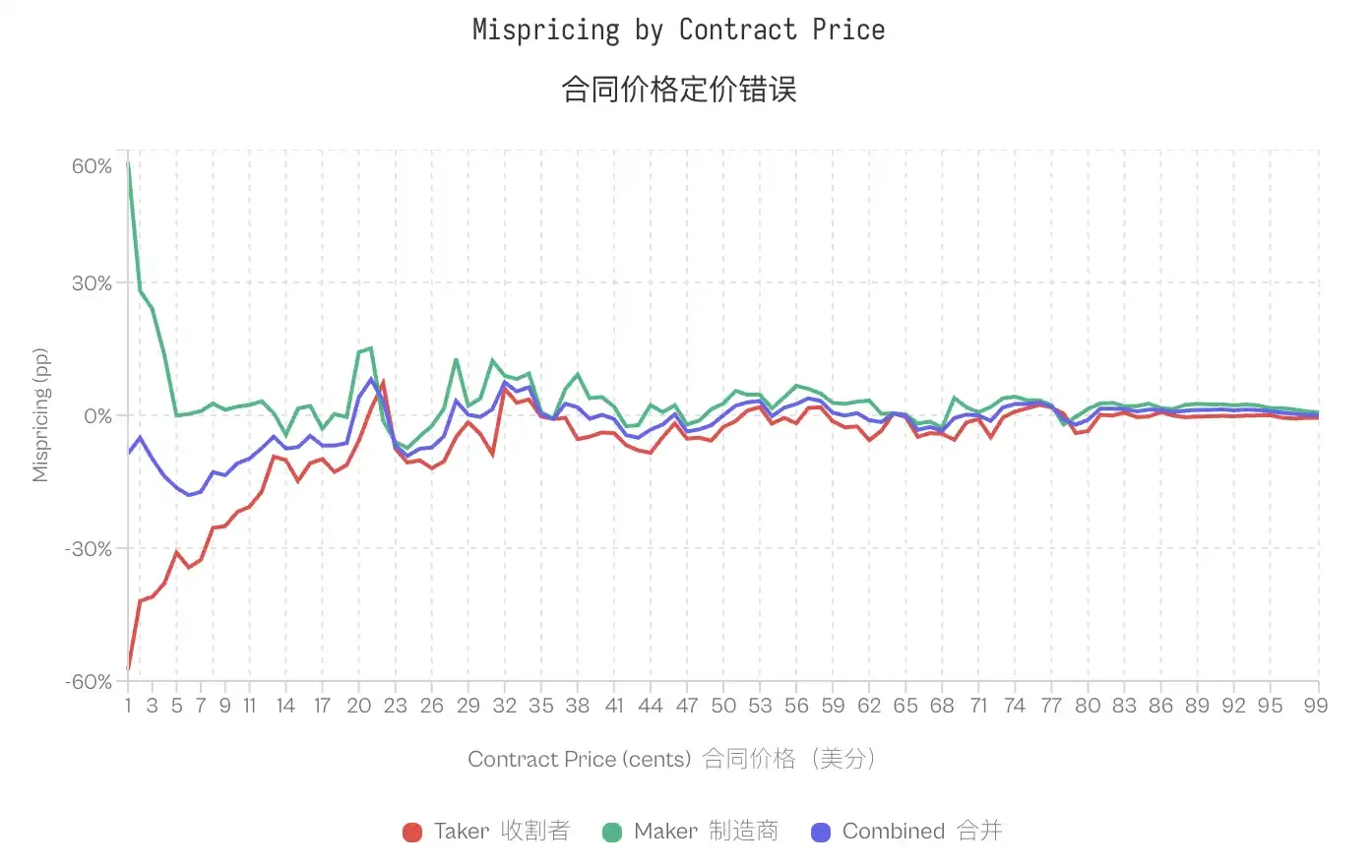

This divergence is most pronounced at the tails. For contracts priced at 1 cent, Takers have a win rate of only 0.43% (implied probability of 1%), corresponding to a -57% mispricing. The win rate for Makers on the same contract is 1.57%, with a mispricing of +57%. At the 50-cent mark, mispricing compresses; Takers show -2.65%, while Makers show +2.66%. At 80 of the 99 price levels, Takers exhibit negative excess returns, while Makers show positive returns at the same 80 levels.

The overall misalignment in the market is concentrated among specific groups: Takers incur losses, while Makers reap gains.

Is this merely spread compensation?

An obvious counterargument is that Makers earn the bid-ask spread as compensation for providing liquidity. Their positive returns may simply reflect spread capture rather than exploiting biased flows of funds.

While this seems reasonable, two observations suggest otherwise. First, the returns for Makers depend on the direction they take. If profits were purely based on the spread, it should not matter whether Makers buy YES or NO.

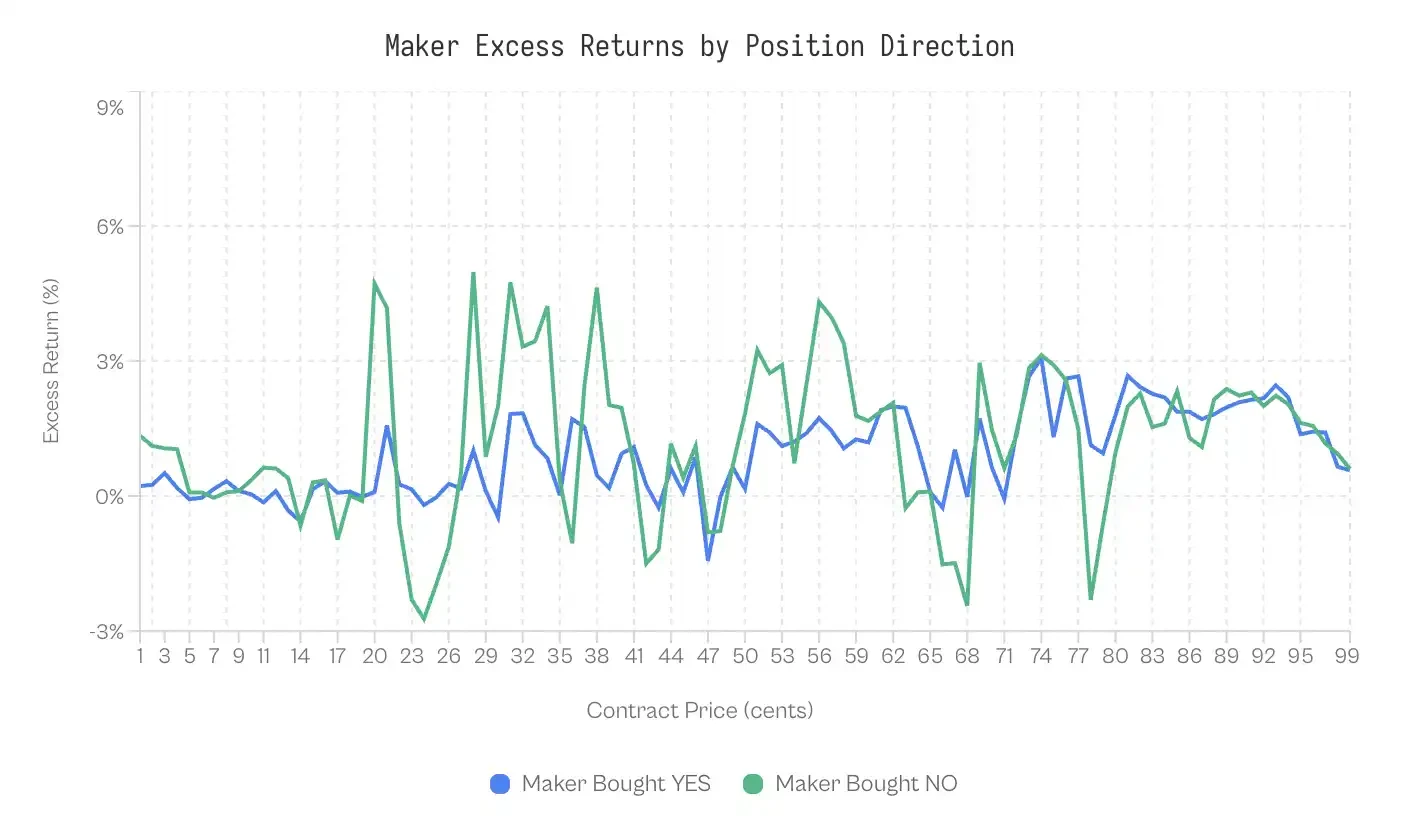

We tested this by breaking down Maker performance by position direction:

Makers buying NO outperform those buying YES 59% of the time.

Makers buying YES have a weighted excess return of +0.77%, while those buying NO have +1.25%. The difference is 0.47 percentage points. Although this effect is minimal (Cohen's d = 0.02-0.03), it is stable.

At the very least, this indicates that spread capture is not the sole reason.

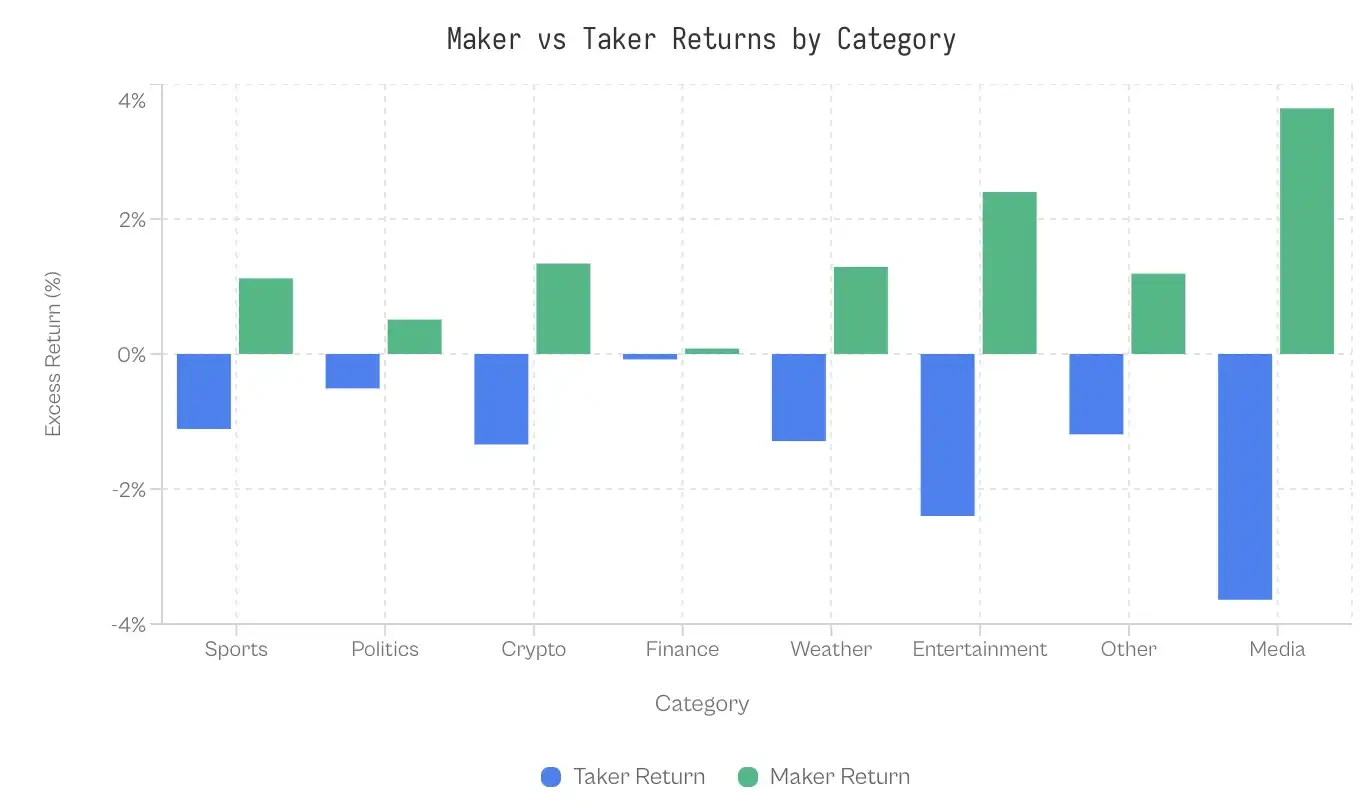

Differences Across Market Categories

If the irrational demand leading to bias is not understood, categories attracting less mature participants should show greater disparities. The data is shocking: the financial category shows only a 0.17 percentage point difference; the market is extremely efficient.

On the other hand, the gap between global events and media representation exceeds 7 percentage points. Sports, as the category with the highest trading volume, shows a moderate gap of 2.23 percentage points. Considering the $6.1 billion in Taker volume, even this moderate gap results in a significant transfer of wealth.

Why is the financial category so efficient? A possible explanation is participant selection; financial issues attract traders who think in terms of probabilities and expected values, rather than fans betting on their home teams. The questions themselves are rather dull (e.g., "Will the S&P index close above 6000 points?"), which filters out emotional bettors.

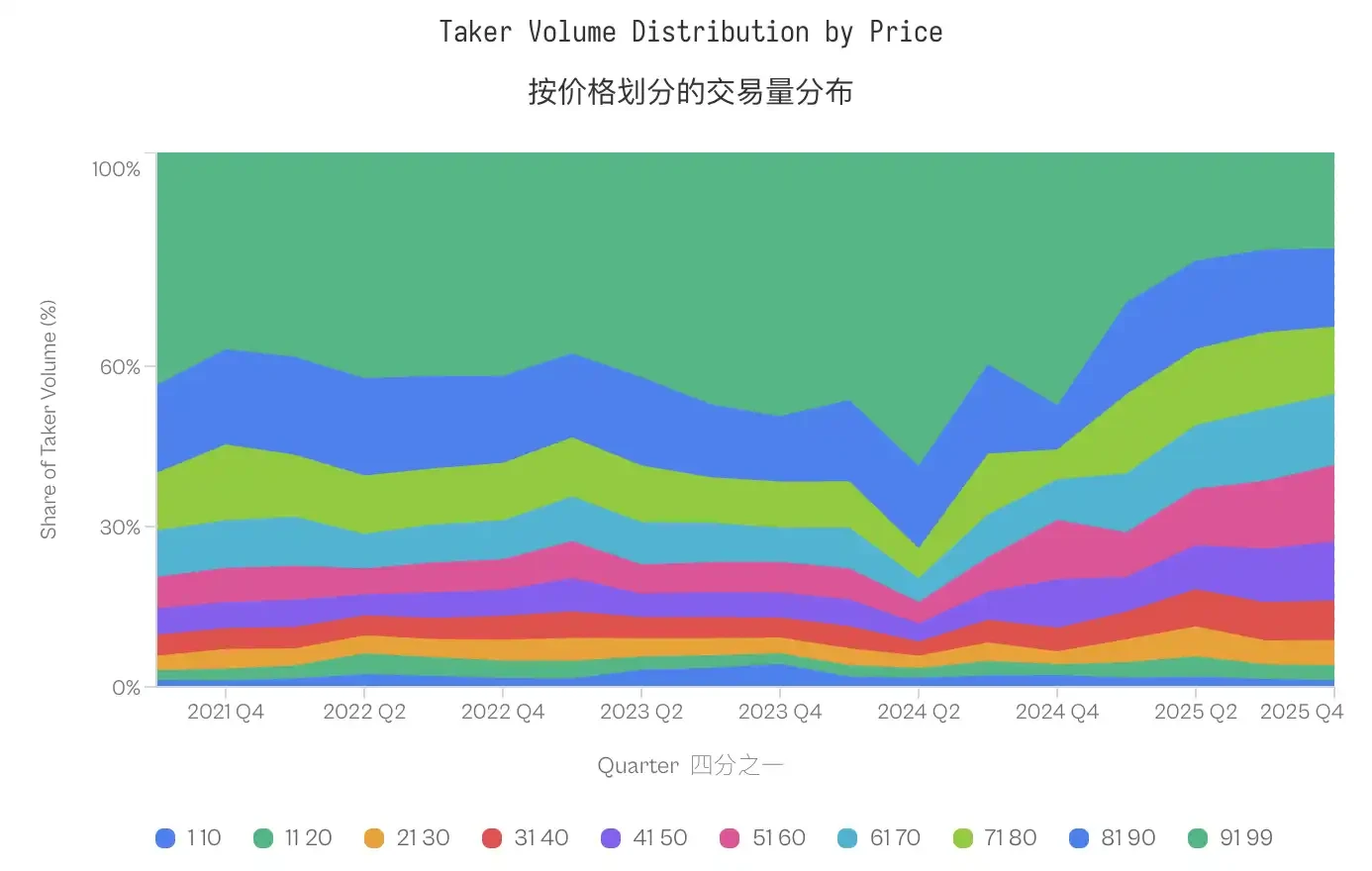

Evolution of Takers and Makers

The gap between Makers and Takers is not an inherent feature of the market; it emerged as the platform developed. In the early days of Kalshi, the pattern was the opposite: Takers earned positive excess returns while Makers lost.

From launch until 2023, Takers had an average return of +2.0%, while Makers had -2.0%. Without mature counterparties, Takers won; amateur Makers defined the early stage and became the losers.

This situation began to reverse in the second quarter of 2024, with the gap sharply widening after the 2024 elections.

The turning point coincided with two events: Kalshi's victory over the CFTC in October 2024 to obtain political contract licenses, and the subsequent 2024 election cycle. Trading volume surged from $30 million in Q3 2024 to $820 million in Q4. New funds attracted mature market makers, leading to the extraction of value from the Taker flow.

Before the elections, the average gap was -2.9 pp (Takers winning); after the elections, it flipped to +2.5 pp (Makers winning).

The trading volume share of low-probability contracts (1-20 cents) remained relatively stable, at 4.8% before the elections and 4.6% after. However, the distribution actually shifted towards mid-price levels; the share of contracts priced at 91-99 cents dropped from 40-50% between 2021-2023 to less than 20% in 2025, while mid-range prices (31-70 cents) saw significant growth.

The behavior of Takers did not become more extreme (the share of low-probability contracts even slightly decreased), but their losses increased.

This evolution reshaped the overall results. The transfer of wealth from traders to market makers is not an inherent feature of prediction market microstructure; it requires mature market makers, and mature market makers need sufficient trading volume to justify their participation.

In the low-volume early stages, market makers were likely inexperienced individuals who lost to relatively informed traders.

The surge in trading volume attracted professional liquidity providers who could systematically extract value from the flow of funds at all price points.

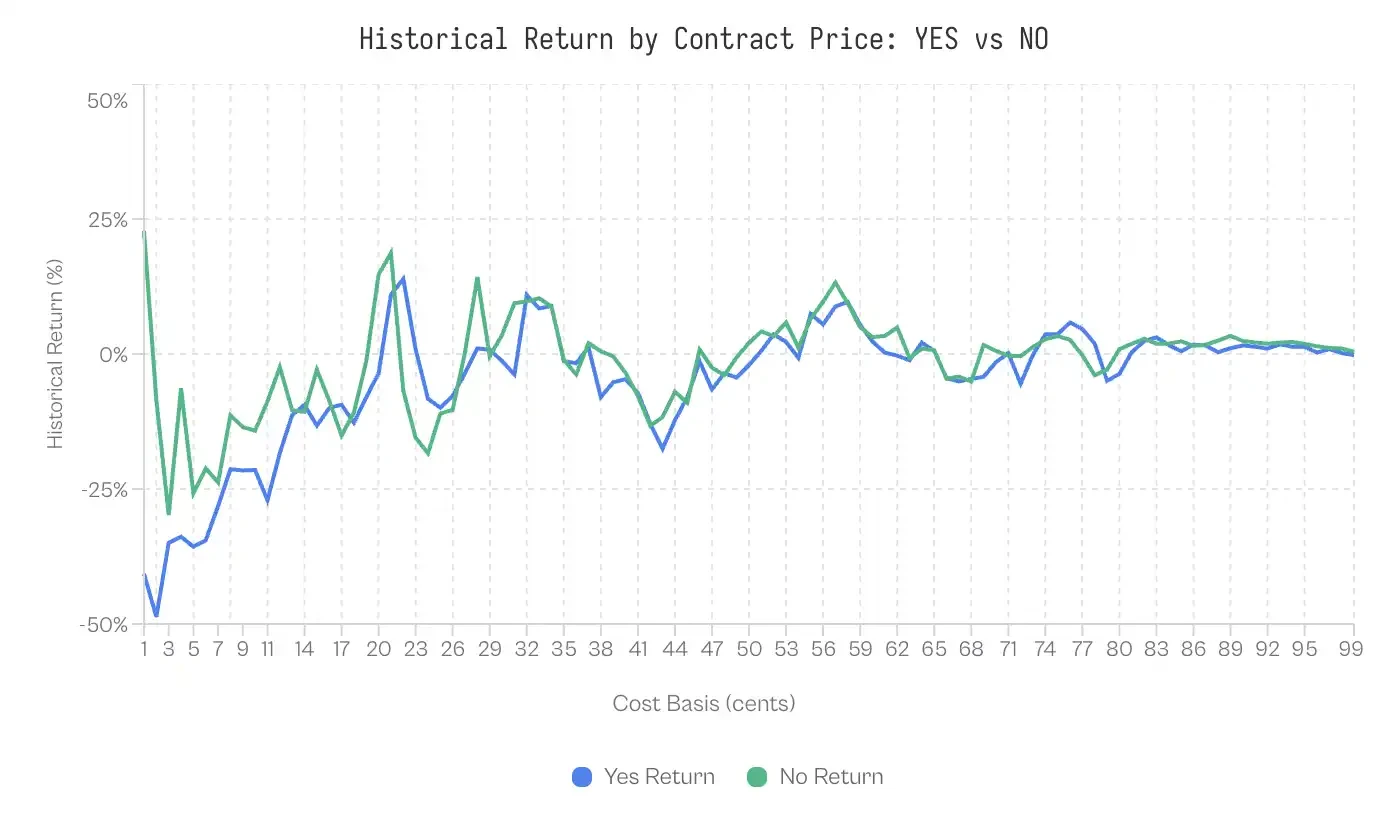

YES/NO Asymmetry

The breakdown of Makers and Takers identifies who absorbs the losses but leaves the question of how this operates. Why is the pricing of Taker flows always incorrect? The answer lies not in the superior predictive ability of Makers, but in the expensive preference of Takers for affirmative outcomes.

Asymmetry at Equal Prices

Standard efficiency models suggest that pricing biases for different contract types at the same price should be symmetric; theoretically, a 1-cent "YES" contract and a 1-cent "NO" contract should reflect similar expected returns.

However, the data contradicts this. At a price of 1 cent, the historical expected return for "YES" is -41%; YES buyers expect to lose nearly half of their principal. In contrast, the historical expected return for a 1-cent "NO" contract is +23%. The difference between these seemingly identical probability estimates reaches as high as 64 percentage points.

The advantage of NO contracts persists. Among the 99 price levels, NO contracts outperform YES contracts at 69 of those levels, with the advantage primarily concentrated at the market's extreme price points. NO contracts generate higher returns at every price increment from 1 cent to 10 cents and from 91 cents to 99 cents.

Although the market is a zero-sum game, the dollar-weighted return for "YES" buyers is -1.02%, while the dollar-weighted return for "NO" buyers is +0.83%, a difference of 1.85 percentage points, caused by the overpricing of "YES."

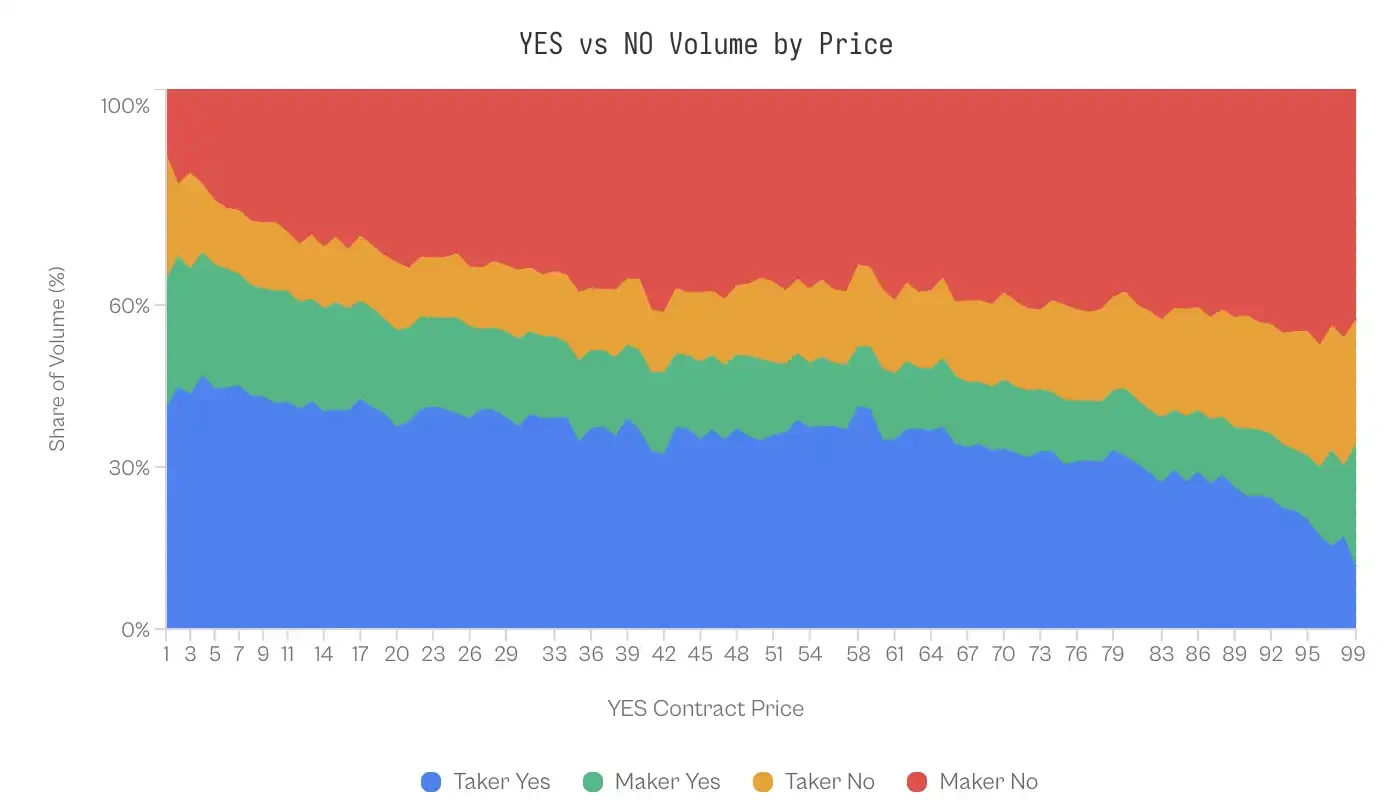

Takers Prefer Affirmative Bets

The poor performance of YES contracts may relate to trader behavior. An analysis of trading data reveals a structural imbalance in the composition of order flow.

In the 1-10 cent range (where YES represents longshot outcomes), Takers account for 41-47% of YES trading volume; Makers only account for 20-24%. This imbalance reverses at the other end of the probability curve. When the contract trading price is 99 cents (implying NO is a 1-cent longshot), Makers actively purchase NO contracts (accounting for 43% of trading volume), while Takers only account for 23%.

One might assume that market makers exploit this asymmetry, profiting from more accurate directional predictions—that is, they know when to buy NO. However, the evidence does not support this assumption.

When breaking down Maker performance by position direction, the returns are nearly identical. Only at the extreme tails (1-10 cents and 91-99 cents) do statistically significant differences appear, and even in these tails, the effect size is minimal (Cohen's d = 0.02-0.03).

This symmetry is significant: market makers do not profit by predicting direction but rather through some mechanism that applies equally to both directions.

Discussion

The analysis of 72.1 million trades on the Kalshi platform reveals a unique market microstructure: wealth systematically transfers from liquidity takers to liquidity creators. This phenomenon is driven by specific behavioral biases and moderated by market maturity, concentrated in categories that can elicit high emotional investment.

Profit Extraction Mechanism of Winners

In a zero-sum market, do winners prevail through superior information (predictions) or superior structure (market making)?

The data strongly supports the latter.

When breaking down Maker returns by position direction, the performance gap is minimal: market makers buying "YES" earn +0.77% excess returns, while those buying "NO" earn +1.25% excess returns (Cohen's d ≈ 0.02).

This statistical symmetry indicates that market makers do not possess significant predictive abilities for winners. Instead, they profit through structural arbitrage: providing liquidity to the group of Takers who prefer high-risk, high-reward outcomes.

This extraction mechanism relies on the "Optimism Tax."

Despite the performance of low-probability "YES" being 64 percentage points lower than that of low-probability "NO," traders still disproportionately buy "YES" contracts at low-probability prices, accounting for nearly half of the total trading volume in that price range.

Thus, market makers do not need to predict the future; they merely need to act as counter-parties to optimistic sentiment. This aligns with the findings of Reichenbach and Walther (2025) on Polymarket and Whelan (2025) on Betfair, indicating that in prediction markets, market makers provide trading flows that adapt to this bias rather than making predictions.

Specialization of Liquidity

Between 2021 and 2023, despite the Longshot Bias, Takers were still able to achieve positive returns. The reversal of this trend coincides precisely with the surge in trading volume following Kalshi's legal victory in October 2024.

The wealth transfer observed at the end of 2024 is a function of market depth. In the early stages of the platform, low liquidity hindered the entry of mature algorithmic market makers. The massive trading following the 2024 elections incentivized the entry of professional liquidity providers who could systematically capture spreads and exploit biased flows of funds.

Differences Between Markets

The differences in the Taker-Maker gap across categories reveal how participant selection shapes market efficiency.

• Finance (0.17 pp): As a control group, it demonstrates that prediction markets can approach efficiency. Questions like "Will the S&P 500 index close above 6000 points?" attract participants who think in terms of probabilities and expected values, likely also being options traders or macroeconomic data followers. The threshold for informed participation is high, ordinary bettors have no advantage, and they are likely aware of this, leading them to opt out.

• Politics (1.02 pp): While involving strong emotional factors, its predictive efficiency still shows some degree of inadequacy. Political bettors closely monitor polls and continuously adjust their judgments throughout the election cycle. This gap is larger than in finance but much smaller than in entertainment, indicating that while political participation is emotionally charged, it does not completely undermine probabilistic reasoning.

• Sports (2.23 pp): This is the category with the highest share in prediction markets. Although the gap is not large, considering that this category accounts for 72% of trading volume, it remains significant. Sports bettors exhibit some verifiable preferences, including loyalty to home teams, recency effects, and emotional attachment to star players. Fans betting on their supported teams to win championships are not calculating expected returns but are buying hope.

• Cryptocurrency (2.69 pp): The participants attracted are heavily influenced by the retail "price up" mentality, overlapping with meme traders and NFT speculators. Questions like "Will Bitcoin reach $100,000?" tend to be bets based more on narrative than on probability estimates.

• Entertainment, media, and global events (4.79–7.32 pp): These areas exhibit the largest cognitive gaps and share a common feature: the low threshold for individuals' perception of their expertise. Anyone following celebrity gossip feels qualified to predict award ceremony outcomes; anyone reading news headlines feels they understand geopolitics. This leads the participant pool to conflate familiarity with judgment.

Our research indicates that market efficiency depends on two factors: the technical threshold for informed participation and the degree to which the market's implied questions evoke emotional reasoning.

When the market threshold is high and the framework is objective and calm, market efficiency approaches an ideal state; when the threshold is low and the framework encourages narrative, the optimism effect peaks.

Limitations

Although the data used in the study is reliable, there are still some limitations.

First, due to the lack of unique trader IDs, we can only rely on the "Maker/Taker" classification to represent "mature/immature" traders. While this is standard practice in microstructure literature, it does not perfectly capture the situation where mature traders engage in cross-trading using timely information.

Second, we cannot directly observe the bid-ask spread from historical trading data, making it difficult to completely distinguish between capturing the spread and the behavior of exploiting biased flows.

Finally, these results apply only to the U.S. regulatory environment; offshore trading venues with different leverage limits and fee structures may exhibit different dynamics.

Conclusion

The promise of prediction markets lies in their ability to aggregate diverse information into a single, accurate probability.

However, our analysis of Kalshi indicates that this signal is often distorted by systematic wealth transfers driven by human psychology and market microstructure.

The market splits into two distinctly different groups: a Taker class that systematically pays too high a price for low-probability, affirmative outcomes, and a Maker class that extracts this premium by passively providing liquidity.

When the topics are dull and quantitative (such as finance), the market is efficient. When the topics allow hope to intervene (such as sports and entertainment), the market transforms into a mechanism that transfers wealth from optimists to actuaries.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。