Written by: Prathik Desai

Translated by: Block unicorn

At the beginning of this year, the cryptocurrency sector has witnessed several significant events. A new round of tariff wars between the US and Europe has once again pushed uncertainty to the forefront. Following that, last week saw an unprecedented wave of liquidations.

Tariffs were not the only negative news at the start of the year. Several initial coin offerings (ICOs) over the past week have given us ample reason to revisit a hot topic in the cryptocurrency community from nearly a decade ago.

Those familiar with the history of cryptocurrency might think that the sector has moved beyond the ICO era of 2017. Although ICOs have undergone many changes since then, the two ICO transactions from last week raised many important questions, some of which have been long-standing, while others are entirely new.

Both Trove and Ranger's ICOs experienced oversubscription, but without the overwhelming Telegram-style countdown promotions seen in 2017. Nevertheless, the process of these events still reminded the community that the fairness of the allocation process is crucial.

In today's story, I delve into how the issuance of TROVE and RNGR reflects the evolving trends of ICOs and the trust mechanisms investors have in the allocation process.

Let’s get to the point.

Trove's ICO was recently held from January 8 to 11, raising over $11.5 million, more than 4.5 times its initial target of $2.5 million. The oversubscription clearly indicated investor support and confidence in the project, which is positioned as a perpetual exchange.

Trove initially planned to build the project on Hyperliquid to leverage the ecosystem's permanent infrastructure and community advantages. However, just a few days after the funding was completed and before the token generation event (TGE) began, Trove suddenly changed its mind and announced it would launch the project on Solana instead of Hyperliquid. This left investors who had confidence in Trove based on Hyperliquid's reputation feeling disappointed.

This move unsettled investors and caused confusion. When another detail came to light, the chaos intensified. Trove's officials stated that they would retain about $9.4 million of the raised funds for a redesigned plan, only refunding the remaining few million dollars. This was another warning sign.

Ultimately, Trove had to respond.

"We will not take the money and run," they stated on X.

The team insisted that the project remains focused on building, just with a changed approach.

Even without making any assumptions, one thing is clear: it is hard to imagine that investors were not treated in an unfair, retroactive manner. Although the funds were originally promised to be invested in a single ecosystem—Hyperliquid, a single technological path, and an implied risk characteristic—the revised plan required them to accept a different set of assumptions without reopening the terms of participation.

It’s like changing the rules of the game for one player after the game has already started.

But by then, the damage was done, and the market punished the loss of confidence. The TROVE token plummeted over 75% within 24 hours of its launch, nearly erasing all its implied valuation.

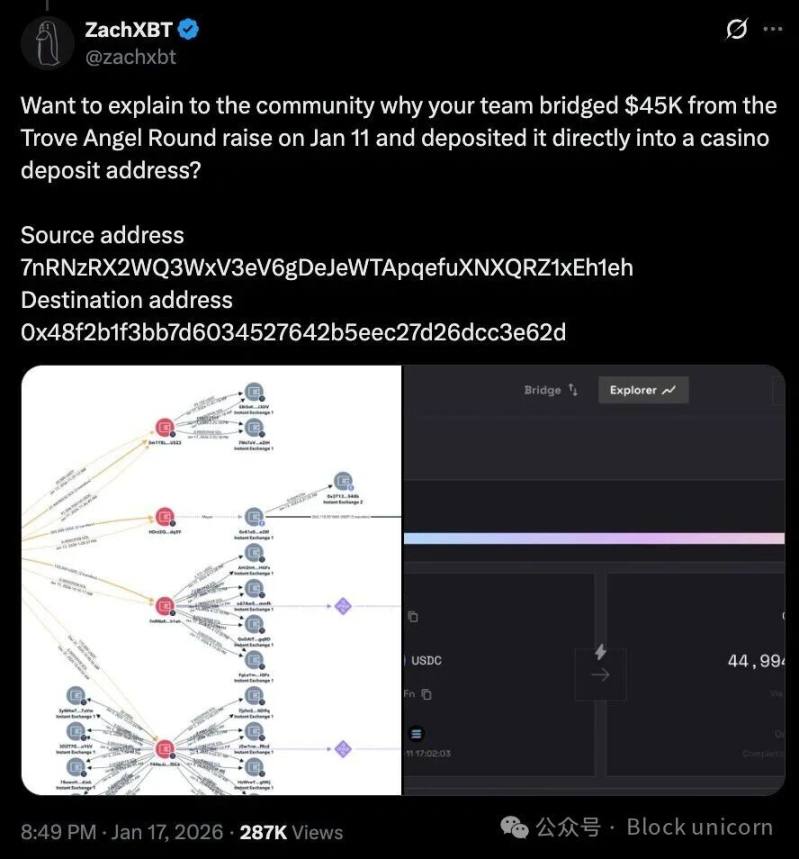

Some in the community no longer acted solely on intuition but began to analyze on-chain transaction dynamics. Cryptocurrency detective ZachXBT discovered that about $45,000 in USDC from the angel round financing eventually appeared on platforms like prediction markets and even flowed into an address associated with gambling.

Whether this was an accounting oversight, poor fund management, or a genuine security risk remains to be seen. Many users criticized the refund process, pointing out that only a small portion of those eligible for refunds received them on time.

Amid all this, Trove's statement failed to reassure those investors who felt betrayed. Although the statement emphasized that the project would continue, specifically building a perpetual exchange on Solana, it did not adequately address the economic concerns raised by this transition. The statement did not provide updated details on how the retained funds would be deployed and managed, nor did it offer any further clarification on the refund roadmap.

While there is no conclusive evidence linking the team's transition to misconduct, this incident illustrates that once trust in the fundraising process diminishes, every data point is more easily interpreted with suspicion.

What makes this situation even more untenable is how the team handled the matter after the fundraising activity concluded.

Oversubscription effectively shifted both funds and decision-making power to the developers. Once the team transitioned, investors had little choice but to exit in the secondary market or exert public pressure.

In some ways, Trove's ICO is similar to many previous ICOs. While its mechanisms are clearer and its infrastructure more mature, both cycles share a common issue: the trust problem. Investors still have to rely on the team's judgment without a clear process to depend on.

The ICO of Ranger, conducted a few days earlier, provides a stark contrast.

Ranger's token issuance took place from January 6 to 10 on the MetaDAO platform. This platform required the team to predefine key fundraising and allocation rules before the sale began. Once launched, these rules could not be changed by the team.

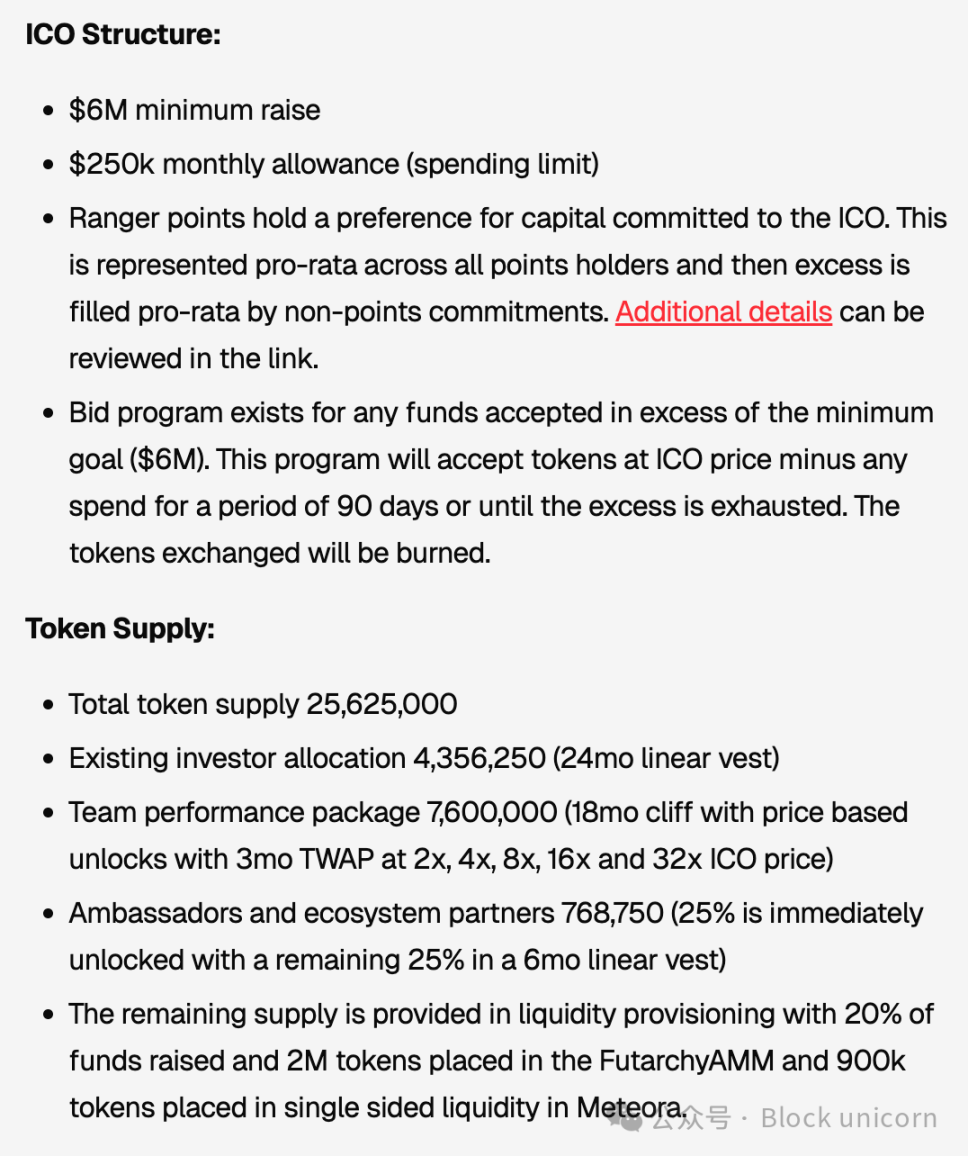

Ranger sought to raise at least $6 million and sold about 39% of the total token supply through a public offering. Like Trove, this issuance also experienced oversubscription. However, unlike Trove, the team was prepared for the oversubscription due to MetaDAO's restrictions.

When the token issuance was oversubscribed, the proceeds were deposited into a treasury managed by token holders. MetaDAO's rules also stipulated that the team could only access a fixed amount of $250,000 from the treasury each month.

Even the allocation structure was defined more clearly. Participants in the public ICO received full liquidity at the token generation event, while presale investors faced a 24-month linear lock-up period. Most of the tokens allocated to the team would only unlock when the RNGR token reached specific price milestones. These milestones, such as 2x, 4x, 8x, 16x, and 32x the ICO price, would be measured using a three-month time-weighted average, with at least an 18-month wait before unlocking.

These measures indicate that the team set limitations within the fundraising structure itself, rather than relying on investors to depend on the team's discretion after fundraising. Control over the funds was partially delegated to corporate governance rules, and any profits for the team were tied to long-term market performance, thereby protecting investors from the risk of capital loss in the early stages of the project.

Nevertheless, concerns about fairness remain.

Like many modern ICO projects, Ranger adopted a proportional allocation model in the case of oversubscription. This means that everyone should receive tokens in proportion to their contributions. At least in theory. However, research by Blockworks indicates that this model often favors participants who can afford to oversubscribe. Smaller contributors typically receive a disproportionate allocation of tokens.

But there is no simple solution to this.

Ranger attempted to address this issue by reserving a separate allocation pool for users who had participated in the ecosystem before the sale. This mitigated the impact but did not completely eliminate the dilemma of choosing between broadly acquiring tokens and actually owning them.

The data from Trove and Ranger collectively indicate that ICOs still face many limitations nearly a decade after their initial explosion. The old ICO model heavily relied on Telegram announcements, narratives, and market hype.

Newer models depend on structured mechanisms to demonstrate their restraint, including vesting schedules, governance frameworks, fund management rules, and allocation formulas. These tools are often mandated by platforms like MetaDAO, helping to limit the discretion of issuing teams. However, these tools can only reduce risk, not eliminate it entirely.

These events raise key questions that every team needs to answer in future ICOs: "Who decides when the team can change plans?" "Who controls the capital after fundraising is complete?" "What mechanisms are available to contributors when expectations are not met?"

These events have sparked some critical questions that every ICO project team will need to address in the future: "Who decides when the team can change plans?" "Who controls the funds after fundraising is completed?" "What remedies are available to contributors when expectations are not met?"

However, the case of Trove does need correction. Changing the blockchain on which the project plan is launched cannot be a decision made overnight. The best way to make amends is for Trove to properly handle its relationship with investors. In this case, that might mean full refunds and a re-sale under the revised assumptions.

While this is the best solution, Trove still faces significant challenges in achieving it. Funds may have already been allocated, operational costs may have been incurred, and partial refunds may have already been issued. Withdrawing operations at this stage could lead to legal, logistical, and reputational complexities. But these are the costs of remedying the chaos that has led to the current situation.

Trove's next steps could set a precedent for ICOs this year. The ICO market is returning to a more cautious environment, where participants no longer misinterpret oversubscription as consensus and no longer confuse participation with protection for fundraisers. Only a well-structured system can provide a trustworthy (if not foolproof) crowdfunding experience.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。