Original Title: The Palantirization of everything

Original Author: Marc Andrusko, a16z Partner

Original Translation: Deep Tide TechFlow

Introduction: Silicon Valley is experiencing a wave of "Palantirization" — AI startups are emulating Palantir by deploying engineers on-site with clients, providing highly customized services, and signing seven-figure deals.

a16z partner Marc Andrusko poured cold water on this trend: the vast majority of companies are merely copying the surface, and will ultimately become consulting firms disguised as SaaS companies. This article breaks down the truly replicable aspects of the Palantir model, as well as those that are merely beautiful illusions.

Main Content:

A popular phrase in startup business plans these days is: "We are basically the Palantir of X domain."

Founders are eager to discuss sending "Forward-Deployed Engineers" (FDEs) to work on-site with clients, creating deeply customized workflows, and operating like special forces rather than traditional software companies. This year, the number of job postings for "Forward-Deployed Engineers" has skyrocketed by hundreds of percentage points, as everyone is copying the model pioneered by Palantir in the early 2010s.

I understand why this approach is appealing. Enterprise clients are currently overwhelmed with the question of "what software to buy" — everything claims to be AI, and distinguishing signal from noise has never been more difficult. Palantir's sales pitch is enticing: drop a small team into a chaotic environment, connect various homegrown, siloed systems, and deliver a customized workflow platform within months. For startups looking to secure their first seven-figure order, the promise of "we will send engineers to sit in your organization and get things done" is a powerful commitment.

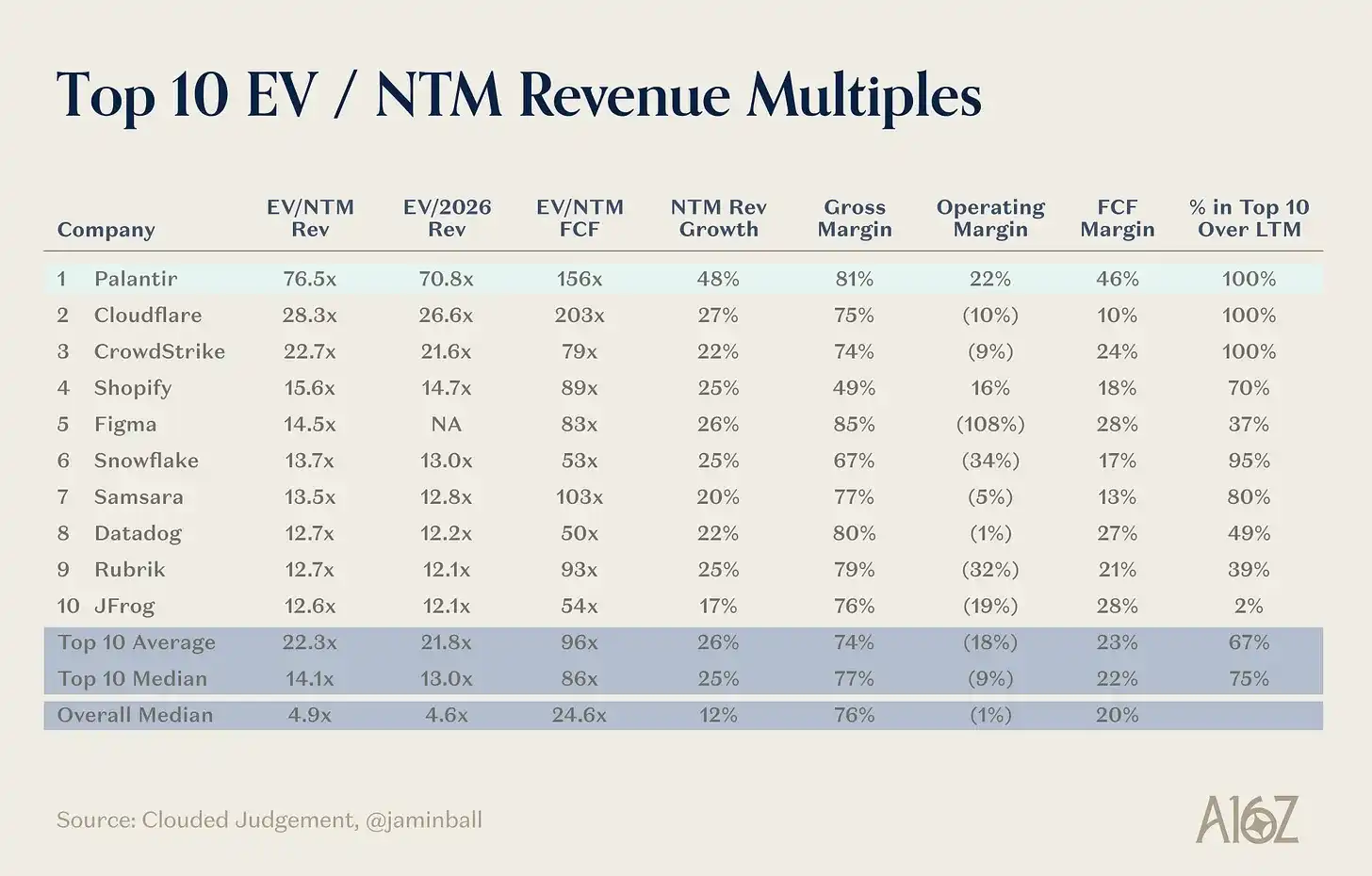

However, I am skeptical that "Palantirization" can be promoted as a universal methodology. Palantir is a "Category of One" — just look at how its stock price trades! Most companies that merely mimic its surface-level tactics will ultimately become expensive service firms, holding software valuation multiples without any compounding competitive advantages. This reminds me of the 2010s when every startup claimed to be a "platform," but there were very few true platform companies because building one is incredibly difficult.

This article aims to clarify the truly transferable aspects of the Palantir model and those that are unique and unreplicable, providing a more pragmatic roadmap for founders looking to combine enterprise software with high-touch services.

What Does "Palantirization" Really Mean

"Palantirization" has come to refer to several interconnected concepts:

Frontline Embedded Engineering

Forward-Deployed Engineers (internally referred to as "Delta" and "Echo" at Palantir) embed within client organizations (often for months), understanding business scenarios, connecting various systems, and building customized workflows on the Foundry platform (or the Gotham platform in high-security environments). Since pricing is fixed-fee, there are traditionally no "SKUs," and engineers are responsible for building and maintaining these capabilities.

Highly Prescriptive Integration Platform

Palantir's products are not a loose collection of tools but rather a platform with a clear proposition for data integration, governance, and operational analytics — more akin to an "operating system" for organizing data. The goal is to transform fragmented data into real-time, high-confidence decisions.

High-End, High-Touch Sales Model

"Palantirization" also describes a sales style: long, high-touch sales cycles targeting mission-critical environments (defense, law enforcement, intelligence, etc.). The complexity of regulation and the scale of industry "stakes" are features, not bugs.

Selling Outcomes, Not Licenses

Revenue comes from multi-year contracts tied to outcomes, blending software, services, and ongoing optimization. Individual client contracts can reach tens of millions of dollars annually.

A recent analysis defined Palantir as a "Category of One" because it excels in three areas: (a) building an integrated product platform, (b) embedding elite engineers into client operations, and (c) proving itself in mission-critical government and defense environments. Most companies can achieve one or two of these, but not all three simultaneously.

By 2025, everyone wants to ride the coattails of this model.

Why Everyone Wants to Copy Palantir Now

Three forces are converging:

1. The "Implementation" Challenge of Enterprise AI

A significant portion of AI projects get stuck before entering production, often due to messy data, integration headaches, and a lack of internal champions. While the willingness to purchase remains fervent (there is real top-down pressure at the board and C-suite levels to "buy AI"), actual deployment and ROI often require a lot of hands-on work.

2. Forward-Deployed Engineers Seem Like the Missing Bridge

Media reports and hiring data show that FDE positions have exploded this year — different sources indicate growth rates between 800% and 1000% — AI startups are embedding engineers to make deployment a reality.

3. Rapid Growth Has Become the Norm (Signing seven-figure deals is easier than quickly scaling five-figure deals)

If sending engineers on-site is the price for securing seven-figure contracts with Fortune 500 companies or government agencies, many early-stage companies are willing to trade margins for momentum. Investors are also increasingly accepting lower margins because new AI experiences often require significant reasoning costs. The bet is: you can win the trust and position of client management, deliver "results," and then price accordingly.

Thus, the narrative has become: "We will do what Palantir has done. We will send in an elite team, create something magical, and then over time turn it into a platform."

This story can hold true under very specific circumstances. However, there are some hard constraints that founders often gloss over.

Where the Analogy Breaks Down

Starting with the Goal of Selling "Outcomes"

Palantir's flagship product, Foundry, is a combination of hundreds of microservices that collectively serve a single outcome. These microservices form productized, prescriptive solutions to common problems faced by enterprises across various domains. Over the past two years, I have met with hundreds of AI application founders, and I can tell you where the analogy breaks down: startups come in pitching a grand set of outcome-based goals, while Palantir consciously built microservices first, which form the foundation of its core capabilities. This is what distinguishes Palantir from ordinary consulting firms (and is also why it trades at a valuation 77 times next year's revenue).

Palantir has a suite of core products:

· Palantir Gotham: A defense and intelligence platform that helps military, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies integrate and analyze dispersed data for mission planning and investigations.

· Palantir Apollo: A software deployment and management platform that securely pushes updates and new features to any environment (multi-cloud, on-premises, disconnected environments).

· Palantir Foundry: A cross-industry data operations platform that integrates data, models, and analytics to drive enterprise operational decisions.

· Palantir Ontology: A dynamic, actionable digital model that organizes real-world entities, relationships, and logic, powering applications and decisions within Foundry.

· Palantir AIP (Artificial Intelligence Platform): Connects AI models (such as large language models) with organizational data and operations through Ontology, creating producible AI-driven workflows and agents.

Citing that Everest report: "Palantir's contracts start small. The initial collaboration may just be a short-term training camp and a limited license. If the value is validated, more use cases, workflows, and data domains will be layered on. Over time, the revenue structure shifts from services to software subscriptions. Unlike consulting firms, services are a means to drive product adoption, not the primary source of revenue. Unlike most software vendors, Palantir is willing to invest its engineering time upfront to secure meaningful clients."

On one hand, I see that AI application companies can often jump straight to seven-figure contracts. On the other hand, this is mainly because they are in a fully customized mode — they are solving any problems thrown at them by early clients, hoping to later identify themes to build core capabilities or "SKUs."

Not Every Problem is a "Palantir-Level" Problem

The areas where Palantir was early to deploy had alternatives that were "not useful at all": counter-terrorism, fraud detection, battlefield logistics, high-risk medical operations. The value of solving these problems is measured in billions of dollars, lives saved, or geopolitical consequences, rather than incremental efficiency.

If you sell to a mid-sized SaaS company and help it optimize its sales process by 8%, you cannot afford the same level of customized deployment. The ROI simply does not support months of on-site engineering.

Most Clients Do Not Want to Be Your R&D Laboratory Forever

Palantir's clients default to accepting the evolution of products alongside it; they tolerate a lot because the stakes are high and alternatives are limited.

Most enterprises, especially outside of defense and regulated sectors, do not want to feel like they are part of a long-term consulting project. They want predictable implementation, interoperability with existing software tools, and quick results.

Talent Density and Culture Cannot Be Generalized

Palantir has spent over a decade recruiting and training exceptionally strong generalist engineers who can write production-level code, navigate bureaucracies, and engage with colonels, CIOs, and regulators in the same room. Those who leave this role form a whole group of founders and executives known as the "Palantir mafia." Many of these individuals are unicorn-level because they are both highly technical and extremely effective in front of clients.

Most startups cannot assume they can hire hundreds of such individuals. In practice, "we will build a Palantir-style FDE team" often devolves into:

· Pre-sales solution engineers rebranded as "FDEs"

· Junior generalists being asked to simultaneously handle product, implementation, and client management

· The leadership has never seen Palantir's deployment up close, but they like the vibe.

It must be made clear that there are many extremely talented people out there, and tools like Cursor are enabling non-technical employees to write code. However, to scale the Palantir model effectively, a rare blend of business and technical talent is required, and having experience at Palantir would be very helpful because it is a very unique company. But the number of such individuals is limited!

The service trap is real.

Palantir works because there is a real platform beneath the custom work. If you only copy the part about embedding engineers, you will end up with thousands of custom deployments that are impossible to maintain or upgrade. Even in a world where AI tools allow companies to achieve software-level gross margins under this model, those that overly lean on frontline deployment without a strong product backbone may fail to generate incremental scale benefits and a lasting moat.

Investors who do not discriminate may see hockey-stick growth from $0 to $10 million in contract value and rush to enter the market. But the question I keep asking is: what happens when dozens (or even hundreds) of such $10 million startups start colliding with identical pitches?

At that point, you are not "the Palantir of X domain." You are "the Accenture of X domain," just with a prettier front end.

What Palantir Did Right

If we strip away the myth, there are several elements worth examining closely:

1. Platform-first, not project-first

Palantir's frontline deployment team builds on a small set of reusable primitives (data models, access controls, workflow engines, visualization components) rather than writing completely custom systems for each client.

2. A clear proposition of how work "should" be done

The company does not just automate existing processes; it often pushes clients toward new ways of working, and the software itself embodies these propositions. This is a rare courage for a vendor, and it makes reuse possible.

3. Long-term vision and capital

Becoming a Palantir-like company requires enduring long periods of negative sentiment, political controversy, and unclear near-term monetization while maturing the platform and sales model.

4. A very specific market combination

The early focus on intelligence and defense is a feature, not a bug: high willingness to pay, high switching costs, high stakes, and a very small number of super-large clients. Not to mention a set of outdated competitors that have been able to secure contracts for decades with little competition.

In other words, Palantir is not just "software company + consulting." It is "software company + consulting + political projects + extremely patient capital."

This is not something you can casually graft onto a vertical SaaS product.

A More Realistic Framework: When is "Palantirization" Reasonable

Instead of asking "How do we become like Palantir," it is better to ask a series of threshold questions:

1. The criticality of the problem

Is the problem "mission-critical" (lives, national security, billions of dollars) or "nice to have" (10-20% efficiency improvement)? The higher the stakes, the more reasonable the frontline deployment model becomes.

2. Customer concentration

Are you selling to dozens of super-large clients or thousands of small clients? Embedded engineering scales better in concentrated, high ACV (annual contract value) customer bases.

3. Degree of fragmentation in the domain

Are the workflows between clients similar, are the software tools used the same, or is every deployment fundamentally different? If every client is a snowflake, it is difficult to build a consistent platform. Some degree of homogeneity is helpful.

4. Regulation and data gravity

Are you operating in highly regulated areas with significant data integration pain points (defense, healthcare, financial crime, critical infrastructure)? That is where Palantir-style integration work can create real value.

If you mostly find yourself in the lower left corner of these dimensions (low criticality, fragmented clients, relatively simple integration), a full "Palantirization" is almost certainly the wrong model. That situation is more suited to a bottom-up PLG (product-led growth) approach.

What is Worth Learning

While I doubt that every early-stage company can successfully deploy the Palantir model, there are several aspects of this approach worth considering:

1. Treat frontline deployment as scaffolding, not the house

The following practices can be entirely correct:

· Have engineers work embedded with early design partners.

· Get the first 3-5 clients into production at all costs.

· Use these collaborations to pressure-test your primitives and abstractions.

But there need to be clear constraints:

· Time-limited deployments (e.g., "90 days to production").

· Clear ratios (e.g., "how many engineering heads per $1 million ARR on a single client").

· Quarterly goals to convert custom code into reusable configurations or templates.

Otherwise, "we will productize later" will turn into "we never got around to it."

2. Build on strong primitives, not custom workflows

The real lesson from Palantir is in product architecture:

· A unified data model and permission layer.

· A common workflow engine and UI primitives.

· Use configuration rather than code whenever possible.

The frontline deployment team should spend time on "choosing" and "validating" which primitives to assemble, rather than building something entirely new for each client. New builds should be left to engineers.

3. Make FDE part of the product, not just delivery

In Palantir's world, frontline deployment engineers are deeply involved in product discovery and iteration, not just implementation. A strong product organization and platform team feed off what FDEs learn in the field.

If your FDEs sit in a separate "professional services" department, you will lose this feedback loop and slide into being a pure service company.

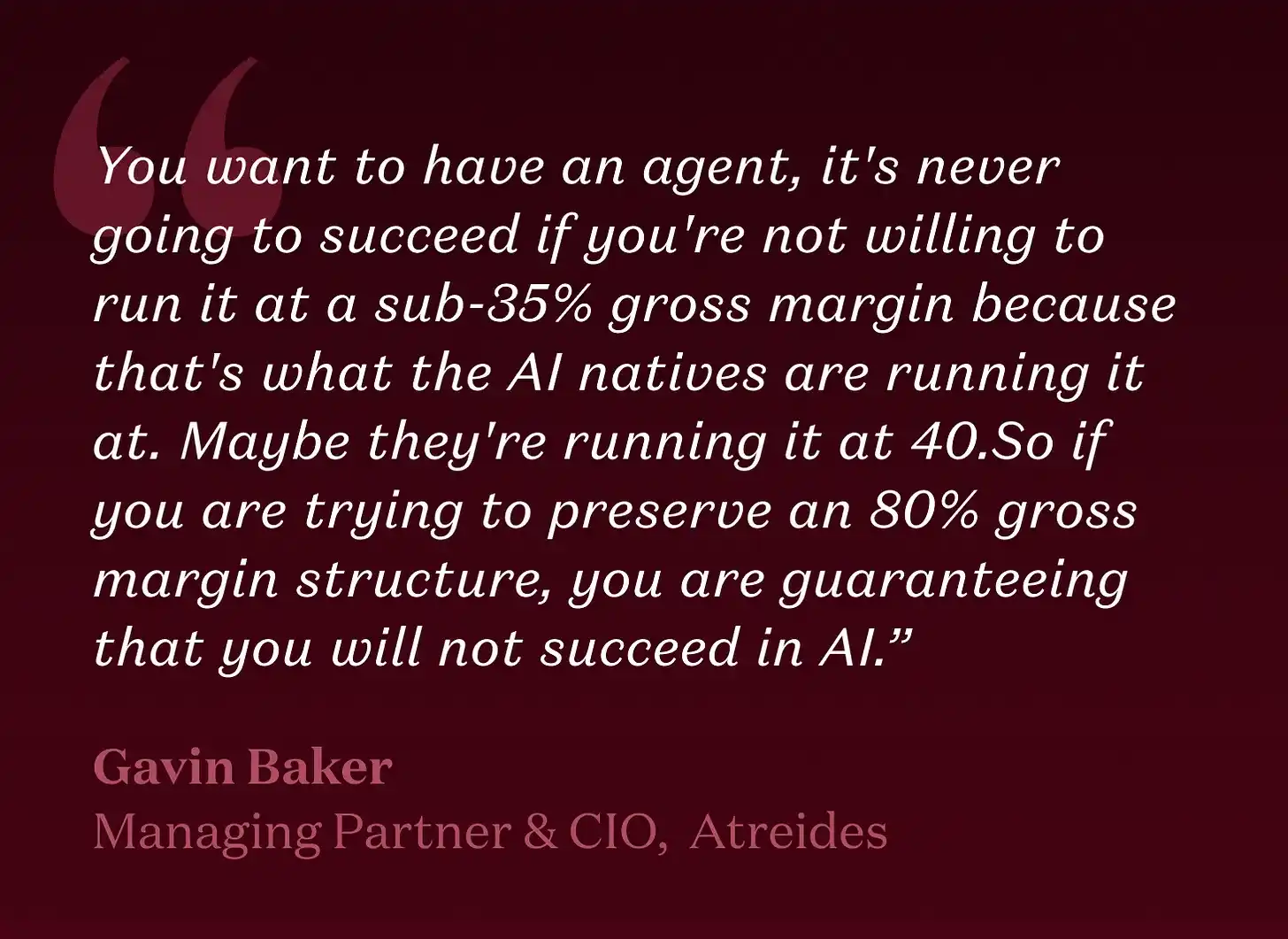

4. Be honest about your gross margin structure

If your pitch assumes over 80% software gross margins and 150% net revenue retention, but your sales model actually requires long-term on-site projects, then be transparent about the trade-offs — at least internally.

For certain categories, a structurally lower margin, higher ACV model is entirely rational. The problem lies in pretending to be SaaS while actually being a service company with a platform. Investors typically look for the path to the maximum absolute gross profit, and one way to achieve that is through larger contracts combined with more significant COGS (cost of goods sold).

How I Would Stress Test a "Palantirized" Startup

When founders tell me, "We are the Palantir of X domain," the questions in my notebook would look something like this:

· Show me a platform boundary with a proposition. Where does the shared product end, and where does client-specific code begin? How quickly does this boundary move?

· Walk me through the deployment timeline. How many engineer-months are needed from signing to first production use? Which parts must be custom?

· What is the gross margin for a mature client in year three? Does the investment in frontline deployment "significantly" decrease over time? If not, why?

· If you sign 50 clients next year, where will it break? Hiring? Training new hires? Product? Support? I want to see where the model cracks.

· How do you decide to say "no" to customization? The willingness to say "no" to custom work is often the key differentiator between a product company and a "service company with a pretty demo."

If these answers are clear, based on real deployments, and architecturally coherent, then a degree of Palantir-style frontline deployment may indeed be a real advantage.

If the answers are vague or clearly indicate that every collaboration is entirely unique, it will be difficult for us to endorse the potential for repeatability or true scalability.

Conclusion

Palantir's success has created a powerful aura that dominates the venture capital startup scene: elite engineering teams parachuting into complex environments, connecting chaotic data, and delivering systems that change the way organizations make decisions.

It is easy to believe that every AI or data startup should look like this. But for most categories, full "Palantirization" is a dangerous fantasy:

· The problems are not critical enough.

· The clients are too fragmented.

· The talent model cannot scale.

· The economic equation quietly collapses into a service company.

For founders, a more useful question is not "How do we become Palantir," but rather:

"How much Palantir-style frontline deployment do we need to bridge the AI adoption gap in our category — and how quickly can we turn it into a real platform business?"

Get this right, and you can borrow the truly important parts of this approach without inheriting those that will weigh you down.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。