In 2025, the Web3 world is not lacking in grand narratives, especially with the completion of regulatory shifts and the gradual integration of stablecoins into the TradFi system. Discussions about "compliance," "integration," and "the next phase of order reconstruction" have almost become the main theme of the year (see further reading: “2025 Global Crypto Regulatory Map: The Beginning of the Integration Era, a Year of Convergence between Crypto and TradFi”).

However, behind these seemingly high-dimensional structural changes, a more fundamental yet long-ignored issue is surfacing: the accounts themselves are becoming a systemic risk source for the entire industry.

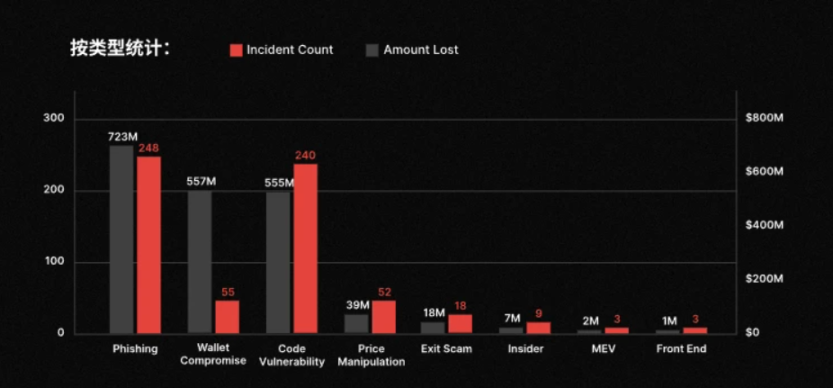

Recently, CertiK's latest security report provided a rather eye-catching figure: in 2025, there were a total of 630 security incidents in Web3, with cumulative losses of approximately $3.35 billion. If we only look at this total figure, it might just be another annual reiteration of the severe security situation. However, when we further break down the types of incidents, we find a more alarming trend:

A significant portion of the losses did not come from complex contract vulnerabilities or direct attacks on the protocol layer, but rather occurred at a more primitive and unsettling level: phishing attacks—with a total of 248 phishing-related incidents throughout the year, resulting in approximately $723 million in losses, even slightly higher than code vulnerability attacks (240 incidents, about $555 million).

In other words, in many cases of user losses, the blockchain did not malfunction, cryptography was not broken, and transactions were entirely compliant with the rules.

The real issue lies with the accounts themselves.

1. EOA Accounts are Becoming Web3's Biggest "Historical Problem"

Objectively speaking, whether in Web2 or Web3, phishing has always been the most common way for people to lose funds.

The difference is that in Web3, the introduction of smart contracts and irreversible execution mechanisms means that when such risks occur, they often result in more extreme outcomes. To understand this, we must return to the most basic and core EOA (Externally Owned Account) account model of Web3:

Its design logic is extremely pure: the private key equals ownership, and the signature equals intent. Whoever holds the private key has complete control over the account. This model was undoubtedly revolutionary in the early stages, bypassing custodians and intermediary systems, directly returning asset sovereignty to individuals.

However, this design also implies an extremely radical premise, meaning that under the assumption of EOA, users will not fall for phishing, will not make mistakes, and will not make erroneous judgments under fatigue, anxiety, or time pressure. As long as a transaction is signed, it is regarded as the user's true and fully understood expression of intent.

Reality, however, is not so.

The frequent security incidents in 2025 are a direct result of this assumption being repeatedly breached. Whether induced to sign malicious transactions or completing transfers without sufficient verification, the commonality lies not in technical complexity but in the account model's inherent lack of fault tolerance for human cognitive limitations (see further reading: “From EOA to Account Abstraction: Will Web3's Next Leap Occur in the 'Account System'?”).

A typical scenario is the long-standing Approval authorization mechanism used on-chain. When users authorize a certain address, they essentially allow the other party to transfer assets from their account without needing to confirm again. In terms of contract logic, this design is efficient and straightforward; however, in real-world use, it frequently becomes the starting point for phishing and asset draining.

For example, in a recent address poisoning incident amounting to $50 million, the attacker did not attempt to breach the system but instead constructed "similar addresses" with highly similar first and last four characters, inducing users to complete transfers in haste. The flaws of the EOA model are clearly exposed here; it is indeed very difficult for anyone to ensure that they can verify a long string of dozens of characters, which has no semantic meaning, in a very short time.

Ultimately, the underlying logic of the EOA model determines that it does not care whether you are deceived; it only cares about one thing: whether you "signed."

This is precisely why successful cases of address poisoning have repeatedly appeared in the news over the past two years, because attackers do not need to engage in the laborious and thankless task of a 51% attack; they only need to create an address that looks sufficiently similar to poison, waiting for users to carelessly copy, paste, and confirm.

After all, EOA cannot determine whether this is a previously unengaged unfamiliar address, nor can it recognize whether this operation significantly deviates from historical behavior patterns. For it, this is merely a legitimate and valid transaction instruction that must be executed. Thus, a long-ignored paradox begins to become unavoidable: Web3 is extremely secure at the cryptographic level but exceptionally fragile at the account level.

So from this perspective, the $3.35 billion industry loss in 2025 cannot simply be attributed to "users not being cautious enough" or "hacker methods upgrading." Instead, it signals that when the account model is pushed to a real financial scale, its historical liabilities begin to manifest.

2. The Historical Inevitability of AA: Systematic Correction of the Web3 Account System

After all, when significant losses occur under conditions where the system "operates completely according to the rules," this itself is the biggest problem.

For example, in CertiK's statistics, phishing attacks, address poisoning, malicious authorizations, and erroneous signatures all share a common premise: the transactions themselves are legal, signatures are valid, and execution is irreversible. They do not violate consensus rules, do not trigger abnormal states, and even appear perfectly normal in block explorers.

From a systemic perspective, these are not attacks but rather correctly executed user instructions.

Ultimately, the EOA model compresses "identity," "authority," and "risk-bearing" into the same private key. Once the signature is completed, identity is confirmed, authority is granted, and risk is borne in a one-time, irrevocable manner. This extreme simplification is an efficiency advantage in the early stages, but as asset scales, participant demographics, and usage scenarios change, it begins to reveal significant institutional flaws.

Especially as Web3 gradually enters a state of high-frequency, cross-protocol, long-term online usage, accounts are no longer just cold wallets used occasionally but are responsible for multiple functions such as payments, authorizations, interactions, and settlements. Under such premises, the assumption that "every signature represents a fully rational decision" has become increasingly difficult to uphold.

From this perspective, the reason address poisoning continues to succeed is not that attackers are smarter, but that the account model has no buffer mechanism for the errors humans are prone to make—the system does not inquire whether this is an unfamiliar object that has never interacted before, nor does it assess whether the amount significantly deviates from historical behavior, and it certainly does not trigger delays or secondary confirmations due to abnormal operations. For EOA, as long as the signature is valid, the transaction must be executed.

In fact, the traditional financial system has long provided answers, whether through transfer limits, cooling-off periods, abnormal freezes, or tiered permissions and revocable authorizations, all essentially acknowledge a simple yet realistic fact: humans are not always rational, and account design must allow for buffer space.

It is against this backdrop that Account Abstraction (AA) begins to reveal its true historical position. It is more like a redefinition of the essence of accounts, aiming to transform accounts from a tool that passively executes signatures into a subject capable of managing intent.

The core lies in the fact that under AA logic, accounts are no longer merely equivalent to a private key; they can have multiple verification paths, set differentiated permissions for different types of operations, delay execution in the event of abnormal behavior, and even regain control under specific conditions.

This is not a departure from the spirit of decentralization but rather a correction of its sustainability. True self-custody does not mean that users must bear permanent consequences for a single mistake; rather, it means that under the premise of not relying on centralized custody, the account itself possesses error-proofing and self-protection capabilities.

3. What Can the Evolution of Accounts Bring to Web3?

I have repeatedly emphasized a statement: "Behind every successful scam, there is a user who stops using Web3, and the Web3 ecosystem will have nowhere to go without any new users."

From this dimension, neither security agencies nor wallet products, nor builders in other sectors, can continue to view "user errors" as individual negligence; they must take on the systemic responsibility of ensuring that the entire account system is sufficiently safe, understandable, and fault-tolerant in real-world usage scenarios.

Therefore, the historical role that AA can play is precisely in this regard. In short, AA is not only a technical upgrade of accounts but also a systematic adjustment of a whole set of security logic.

This change is first reflected in the loosening of the relationship between accounts and private keys. For a long time, mnemonic phrases have been regarded as the passport for self-custody in Web3, but reality has repeatedly proven that this single-point key management approach is not user-friendly for most ordinary users. AA introduces mechanisms such as social recovery, allowing accounts to no longer be tightly bound to a single private key. Users can set multiple trusted guardians, and when a device is lost or a private key fails, they can regain control of the account through verification.

When AA is combined with Passkey, we can even construct a model that truly approaches people's intuitive understanding of account security in the real financial system (see further reading: “Web3 Without Mnemonic Phrases: AA × Passkey, How to Define the Next Decade of Crypto?”).

Equally important is AA's reconstruction of transaction friction. Under the traditional EOA system, gas fees constitute almost all on-chain operations' implicit thresholds, while AA, through mechanisms like Paymaster, allows transaction fees to be paid by third parties or directly using stablecoins.

This means that users no longer need to prepare a small amount of native tokens to complete a transfer, nor are they forced to understand complex gas logic. Objectively speaking, this gas-less experience is not just a bonus but one of the key conditions determining whether Web3 can move beyond the early user circle.

Additionally, AA accounts, through the native capabilities of smart contracts, can package originally fragmented multi-step operations into a single atomic execution. For example, in DEX trading, what used to require multiple steps such as authorization, signing, trading, and re-signing can now be completed in one transaction under AA accounts—either all succeed or all fail—saving costs and avoiding ineffective losses caused by mid-process failures.

Deeper changes are reflected in the malleability of account permissions themselves. AA accounts are no longer a binary structure of "either full control or complete loss of control," but can have a refined permission management logic similar to real-world bank accounts. Different limits correspond to different verification strengths, different entities correspond to different interaction permissions, and accounts can even be restricted to interact only with specific secure contracts through black and white lists.

This means that even in extreme cases where the private key is leaked, the account itself still has a buffer space, preventing assets from being completely drained in a short period.

Of course, it is important to emphasize that the evolution of account security does not solely rely on the comprehensive implementation of the AA account system; existing wallet products can and must also take on part of the responsibility for correcting the EOA model.

Taking imToken as an example, its address book function saves commonly trusted addresses, allowing accounts to rely less on users' immediate judgment of a string of hash characters when transferring funds. Instead, it prioritizes selection from existing addresses, significantly reducing the risk of transfer errors caused by manual copying, pasting, or misjudging similar addresses.

Equally important is the "What You See Is What You Sign" principle, which has gradually become an industry consensus in recent years. Its core is not to display more information but to ensure that the content users sign must align with the actions they see, understand, and expect, rather than being compressed into an unrecognizable hash data.

Around this principle, imToken has structured and presented the content of signatures in a readable format at all key stages involving signatures, including DApp logins, transfers, token exchanges, and authorizations, allowing users to truly understand what they are agreeing to before confirming. This design does not change the irreversibility of transactions but introduces a necessary rational buffer before the signature occurs, which is an indispensable step in the maturation of the account system.

From a broader perspective, the evolution of AA accounts is actually reshaping the foundational assumptions for the next stage of Web3's development, enabling the blockchain to truly accommodate a large number of real users. Otherwise, no matter how complex the protocol or grand the narrative, it will ultimately be repeatedly pierced by a fundamental question—whether ordinary users dare to keep their assets on-chain for the long term.

In this sense, AA is not an added bonus for Web3 but more like a passing line; it determines not whether the experience is good, but whether Web3 can evolve from a system primarily for tech enthusiasts into an inclusive financial infrastructure for a broader audience.

In Conclusion

$3.35 billion is essentially the tuition fee paid by the entire industry in 2025.

This also reminds us that when the industry begins to discuss compliance, institutional interfaces, and mainstream capital entry, if Web3 accounts remain in a state of "signing/authorizing once and clearing," then the so-called financial infrastructure is merely built on sand.

The real question may not be "Will AA become mainstream?" but rather—If accounts do not evolve, how much future can Web3 still accommodate?

This may be the most worth pondering security insight that 2025 leaves for the entire industry.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。