Written by: Will Awang

Introduction: Every era is shaped by its iconic miracle materials. Steel forged the Gilded Age, semiconductors ushered in the digital age. Today, artificial intelligence (AI) makes its appearance as "Infinite Minds." Historical experience tells us: those who master the materials of the era can define the era.

Left image: Young Andrew Carnegie with his brother;

Right image: Pittsburgh steel mills during the Gilded Age

In the 1850s, a young Andrew Carnegie ran through the muddy streets of Pittsburgh, making a living as a telegraph operator. At that time, 60% of Americans were engaged in agriculture. In just two generations, Carnegie and his contemporaries reshaped the modern world: horse-drawn carriages were replaced by railroads, candlelight was illuminated by electric lights, and iron was replaced by steel.

Since then, the human work scene has shifted from factories to office buildings. Today, I run a software company in San Francisco, creating tools for millions of knowledge workers. In this tech industry city, everyone is talking about general artificial intelligence, but the vast majority of the 2 billion white-collar workers worldwide have yet to feel its impact. What will the future form of knowledge work look like? When tireless intelligent agents are integrated into corporate organizational structures, what kind of transformation will it bring?

Early filmmaking techniques resembled stage plays, typically using a single camera to capture the entire stage.

The future is difficult to predict because it always appears dressed in the clothing of the past. Early telephone conversations were as concise as telegrams, and early films resembled recorded stage plays. (This is what Marshall McLuhan referred to as "driving into the future through the rearview mirror.")

The most mainstream applications of artificial intelligence today resemble past Google searches. Again, citing McLuhan's perspective: "We always drive into the future through the rearview mirror."

Currently, the AI chatbots we see are essentially products that mimic the Google search box. Every major technological change goes through an uncomfortable transition period, and we are in the midst of it.

I cannot predict the full picture of the future, but I like to use some historical metaphors to think about how artificial intelligence will play a role across different dimensions—from individuals and organizations to entire economies.

Individuals: From Bicycles to Cars

The prototype of this transformation first appeared among the "pioneers" of knowledge workers—programmers.

My co-founder Simon was once recognized as a "10x programmer," but now he rarely writes code himself. Passing by his workstation, you would see him simultaneously managing three or four AI programming agents. These agents not only type faster but also possess autonomous thinking capabilities, allowing Simon to become an engineer who creates 30-40 times more value. He issues task instructions before lunch or bedtime, enabling the agents to continue working while he is away. He has now become an "infinite intelligence manager."

A 1970s article in Scientific American about mobile efficiency inspired Steve Jobs to propose the famous metaphor of the "bicycle for the mind." Since then, we have been "riding" on the information superhighway for decades.

In the 1980s, Steve Jobs compared personal computers to "bicycles for the mind." A decade later, we laid down the "information superhighway" known as the internet. Yet today, the vast majority of knowledge work still relies on human effort—it's as if we have been riding bicycles on the highway.

With the help of AI agents, people like Simon have completed the leap from "riding a bicycle" to "driving a car."

When will knowledge workers in other fields usher in their own "automobile era"? To achieve this goal, two major challenges must be overcome.

Why is it more challenging for AI to empower general knowledge work compared to programming agents? The reason lies in the more fragmented nature of knowledge work scenarios and the difficulty in verifying outcomes.

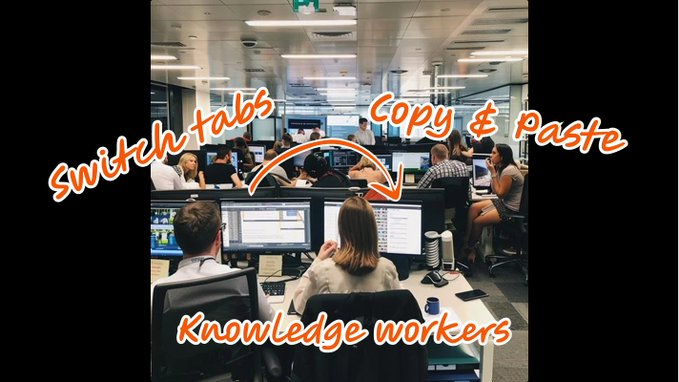

First, scenario fragmentation. The tools and scenarios for programming work are highly concentrated: integrated development environments, code repositories, terminals—these tools work in synergy. However, the scenarios for general knowledge work are scattered across dozens of platforms. Imagine an AI agent tasked with writing a product brief; it would need to retrieve information from discussion records on social collaboration platforms, strategic documents, performance metrics from last quarter's data dashboards, and tacit knowledge that only exists in employees' minds. Currently, humans connect these fragmented pieces of information through copy-pasting and frequent switching between browser tabs. Until scenario information integration is achieved, the application scope of agents can only be limited to specific scenarios.

Second, the lack of verifiability of outcomes. Code has a unique advantage: its effectiveness can be validated through testing and error reporting. Model developers leverage this characteristic to train AI through methods like reinforcement learning to enhance its programming capabilities. But how do we verify whether a project is managed properly? Does a strategic memo hold value? Currently, we have yet to find effective methods to improve the performance of AI models for general knowledge work. Therefore, humans still need to be involved throughout the process, responsible for supervision, guidance, and demonstrating the standards for "quality outcomes" to AI.

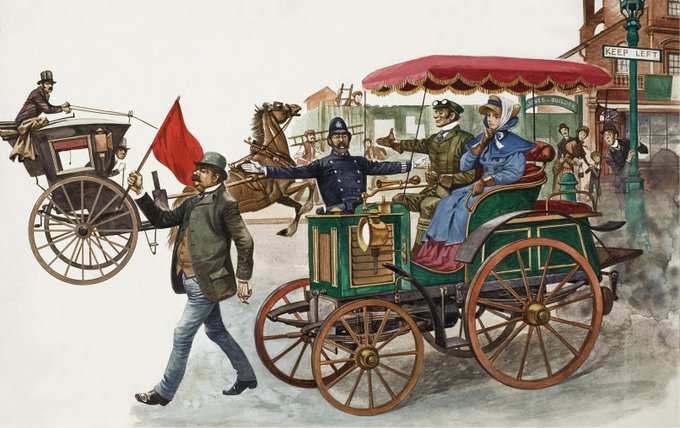

The "Red Flag Act" enacted in 1865 mandated that when motor vehicles were on the road, a person must hold a red flag in front to lead the way (this act was repealed in 1896). This is a typical example of the unreasonable "full human involvement" model.

This year, the practice of programming agents has made us realize that "full human involvement" is not an ideal model. It's akin to arranging for a dedicated person to check every bolt on a factory assembly line or sending someone ahead of a car to clear obstacles (just like the absurd provisions of the 1865 "Red Flag Act"). We hope that humans can supervise workflows more efficiently rather than getting bogged down in tedious details. Once scenario information integration and outcome verifiability are achieved, billions of workers will complete the leap from "riding bicycles" to "driving cars," moving towards a new phase of "autonomous driving."

Organizations: Steel and Steam

Businesses are a relatively recent organizational form, and as they scale, their operational efficiency tends to decline, ultimately hitting a growth ceiling.

The organizational chart of the New York and Erie Railroad Company from 1855. The modern corporate system and organizational charts developed alongside the rise of railroad companies, which were among the first enterprises requiring coordination of thousands of employees and cross-regional operations.

Hundreds of years ago, most businesses were small workshops with only a dozen employees. Today, multinational corporations can employ hundreds of thousands. The "human brain communication network" connected by meetings and messages is overwhelmed under the exponentially increasing business pressure. We attempt to solve this problem through hierarchical structures, process specifications, and documentation, but this essentially uses human tools suitable for small teams to tackle the complex challenges of industrial-scale operations—like building a skyscraper with wood.

Two historical metaphors may reveal how future corporate organizational forms will undergo transformative changes with the help of new era materials.

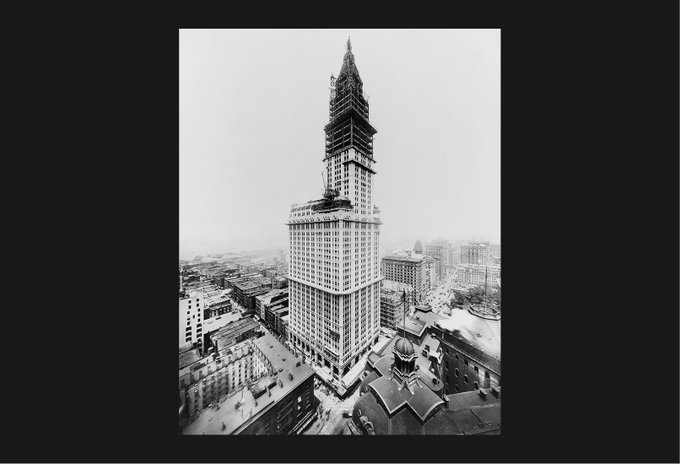

The miracle of steel: The Woolworth Building in New York, completed in 1913, was the tallest building in the world at the time.

The first metaphor is steel. In the 19th century, before the widespread use of steel, the height limit for buildings was only six or seven stories. Cast iron, while strong, was brittle and heavy, causing buildings to collapse under their own weight if they were too tall. The advent of steel changed everything: it combined high strength with ductility, allowing for lighter building frames and thinner walls, giving rise to skyscrapers. A new form of architecture became possible.

Artificial intelligence is the "steel" that empowers corporate organizations. It is expected to break down information barriers in workflows, presenting the information needed for decision-making accurately when required, free from the interference of redundant information. Human communication and collaboration will no longer be the "load-bearing walls" supporting corporate operations. Weekly alignment meetings that once took two hours may be simplified to five minutes of asynchronous review; executive decisions that previously required three layers of approval may be completed in minutes. Companies will finally be able to achieve true scalable expansion, breaking free from the long-standing efficiency decline that has been seen as an "inevitable law."

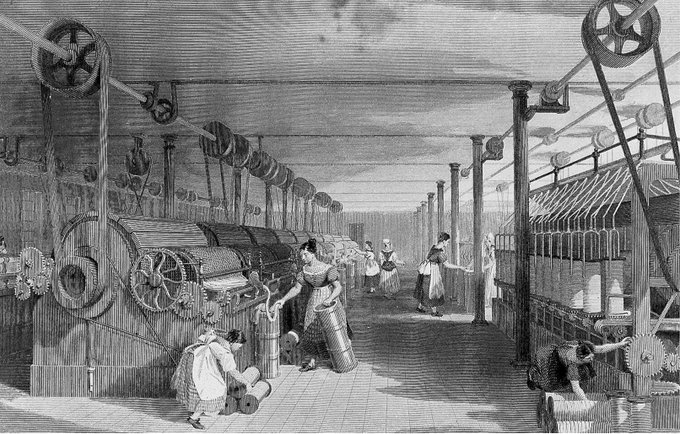

A mill powered by a waterwheel. While hydraulic power is strong, it is unstable and limited by geography and seasons, so mills could only be built along rivers.

The second metaphor is the steam engine. In the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, early textile factories were built near rivers, relying on waterwheels for power. When the steam engine was invented, factory owners initially simply replaced waterwheels with steam engines, keeping all other production modes unchanged, resulting in limited productivity gains.

The real breakthrough came when factory owners realized they could completely free themselves from reliance on hydraulic power. They began constructing larger factories closer to workers, ports, and raw material sources, redesigning factory layouts around steam engines. (Later, with the advent of electricity, factory owners further broke free from the constraints of central drive shafts by equipping different machines with independent motors.) This series of changes led to an explosive increase in productivity, ushering in the wave of the Second Industrial Revolution.

This 1835 engraving by Thomas Allom depicts a steam-powered textile factory in Lancashire, England.

Today, we are still in the initial stage of "replacing waterwheels"—merely awkwardly grafting AI chatbots onto existing tools. We have yet to truly imagine: when the old constraints no longer exist, and businesses can operate with tireless infinite intelligence, what kind of disruptive changes will occur in organizational forms.

At Norton, the company I founded, we have already begun related attempts. Currently, in addition to 1,000 employees, over 700 AI agents are responsible for handling repetitive tasks: they record meeting minutes, answer questions to integrate the company's tacit knowledge; process IT support requests, input customer feedback; assist new employees in understanding benefits policies; and write weekly progress reports, freeing employees from the tedious work of copying and pasting. And this is just the first step of a long journey. The future potential for productivity growth is limited only by our imagination and the inertia of change.

Economy: From Florence to Megacities

The impact of steel and steam extends far beyond buildings and factories—they have fundamentally changed the shape of cities.

Hundreds of years ago, the scale of cities was limited by "human reach." In Florence, it took only 40 minutes to walk across the entire city. The pace of life was determined by walking distances and the range of sound propagation.

Later, steel frameworks made skyscrapers a reality, and steam-powered railways connected city centers with surrounding hinterlands. Elevators, subways, and highways emerged in succession, leading to explosive growth in city size and population density. Tokyo, Chongqing, Dallas… these megacities came into being.

They are not merely "enlarged versions" of Florence, but represent an entirely new way of life. Megacities are dazzling and filled with unfamiliarity, making them harder to explore. This elusive quality is the inevitable cost of scale expansion. Yet at the same time, megacities also bring more opportunities and freedoms—countless people create and connect here, generating possibilities far beyond those of the small, human-powered towns of the Renaissance.

I believe the knowledge economy is about to undergo a similar transformation.

Today, the knowledge economy contributes nearly half of the U.S. GDP. However, the vast majority of knowledge economy activities still operate at a "human scale": small teams of dozens, workflows dominated by meetings and emails, organizations that malfunction when they exceed a few hundred people… We are building "Florentine-style" knowledge economies with "stone and wood."

When AI agents achieve scalable application, we will begin to create a "Tokyo" for the knowledge economy: organizations composed of thousands of human employees and agents working in collaboration; workflows that operate around the clock without time zone restrictions; and a collaborative model where humans intervene in decision-making in the most optimal way.

This new model will inevitably bring a strong sense of "discomfort." It is more efficient and leverages greater effects, but initially, it may leave people feeling lost. Traditional work rhythms like weekly meetings, quarterly planning, and annual assessments may gradually lose their significance. New operational rhythms will emerge; we may lose some "certainty," but in exchange, we will gain scale expansion and leaps in efficiency.

Beyond "Waterwheel Thinking"

Every epoch-making material requires people to let go of the "rearview mirror perspective" and dare to imagine a brand new future. Carnegie gazed at steel and foresaw the infinite possibilities of city skylines; factory owners in Lancashire saw the steam engine and envisioned factory blueprints free from the constraints of rivers.

Today, we are still in the "waterwheel era" of artificial intelligence, merely awkwardly grafting chatbots onto workflows designed for humans. We need to break free from the limitation of "making AI an assistant" and boldly imagine: when human organizations have the support of steel, and tedious tasks are handled by tireless intelligent agents, what new face will knowledge work present?

Steel, steam, infinite intelligence. A brand new city skyline awaits us to forge it with our own hands.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。