Original Title: "The Resurgence of Mining Power in Xinjiang, Quickly Cleared Out Within 48 Hours: What Happened in the Bitcoin Network This Time?"

Written by: Luke

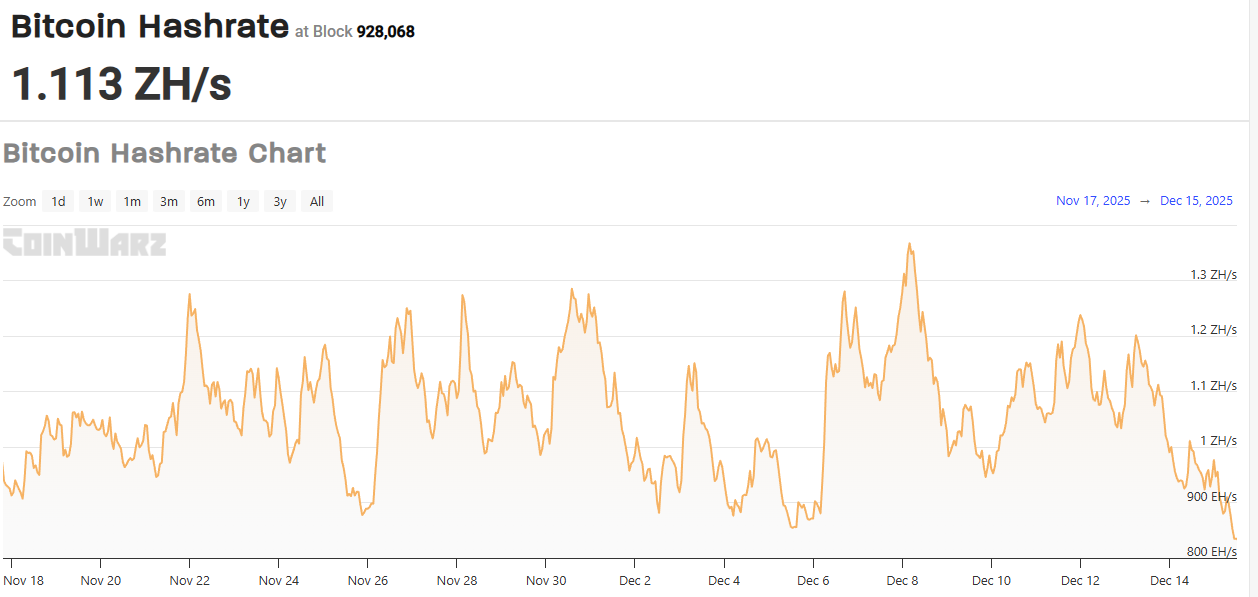

On December 16, Beijing time, the Bitcoin network suddenly hit the brakes. The hash rate curve showed a significant drop within two days, and the explanation from the mining community was highly consistent: multiple mining sites in Xinjiang shut down simultaneously, with some equipment being confiscated or cleared out, leading to a temporary "removal of a chunk" of the network's hash rate. The focus of market debate was not whether the shutdown occurred, but rather the scale of it—rumors ranged from over 200,000 to 400,000 machines.

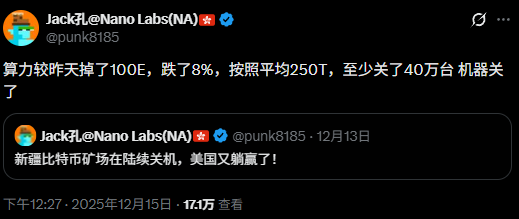

One of the most frequently cited estimates comes from an engineer's algorithm in the mining community: with contemporary main machines averaging about 250 TH/s, if 400,000 machines were to shut down one after another, the corresponding hash rate gap could lead to a drop of nearly 100 EH/s across the entire network. Some have even stated more aggressively that the network's hash rate once dropped from nearly 1200 EH/s to around 836.75 EH/s, a decline of nearly 30%. Different platforms and sources do not completely agree on the "lowest point," but one fact is hard to ignore: this is not just a fluctuation from a few mining sites "shutting down a few racks," but a widespread and concentrated shutdown.

What truly deserves questioning is the narrative of this event: why did mining in Xinjiang rise again under the ban? And why did the clearance come so quickly and forcefully?

Why Did Mining in Xinjiang Resurge?

The underlying motivation for the "resurgence" of mining power in Xinjiang is not a sudden policy shift, but rather three real pressures being squeezed into the same outlet.

The first pressure comes from the energy structure. Xinjiang has a large-scale power supply and industrial distribution system, and during certain periods and in certain areas, the marginal value of electricity consumption is not high. For external delivery channels, scheduling, and demand-side support capabilities, this is a long-term tug-of-war: electricity can be generated, but it is not always sold in an "ideal way." For asset owners, the most painful aspect is not the low electricity price, but the inability to sell electricity; for miners, this creates an energy oasis—if they can get electricity, they can directly convert it into cash flow.

The second pressure comes from data centers and infrastructure. In recent years, data centers have expanded too quickly, leaving a large amount of "electricity already connected, data centers already built" capacity. The AI narrative is hot, but AI does not mean "having a data center guarantees profit": it requires computing power cards, large clients, and long-term stable loads. The reality is that some data centers have not received enough AI orders and do not have sufficient computing power card resources; equipment idling for a day means real losses due to depreciation. Thus, some asset owners treat "filling loads" as a necessity—in the gray area, mining happens to be the easiest filling application: no client or business form requirements, as long as there is power, cooling, and networking, it can run.

The third pressure comes from the temptation of recouping costs and the supply chain. When Bitcoin prices rise, the payback period for mining machines is significantly compressed; in the face of the temptation of "recouping costs in about six months," many people in the gray area view the risks as costs rather than red lines. More critically, the supply chain for mining machines has not disappeared: machines can be purchased, transported, and installed, thus providing the physical conditions for a gray area revival.

The result of the convergence of these three pressures is a shadow resurgence: local assets (electricity + data centers) need cash flow, miners need low-cost electricity, and the supply chain can deliver equipment, making Xinjiang once again a magnet for computing power. It is not a gathering place for miners' sentiments, but a place where an energy oasis and infrastructure oasis overlap.

This also explains a seemingly contradictory phenomenon: the ban has not disappeared, but mining will still periodically resurface. It is not because the red line has loosened, but because the constraints of real assets never stop: electricity, data centers, distribution, depreciation, and cash flow will all force participants to repeatedly test the boundaries.

Is Mining Illegal in China? Elimination Does Not Equal Criminal Offense, but the Red Line Remains

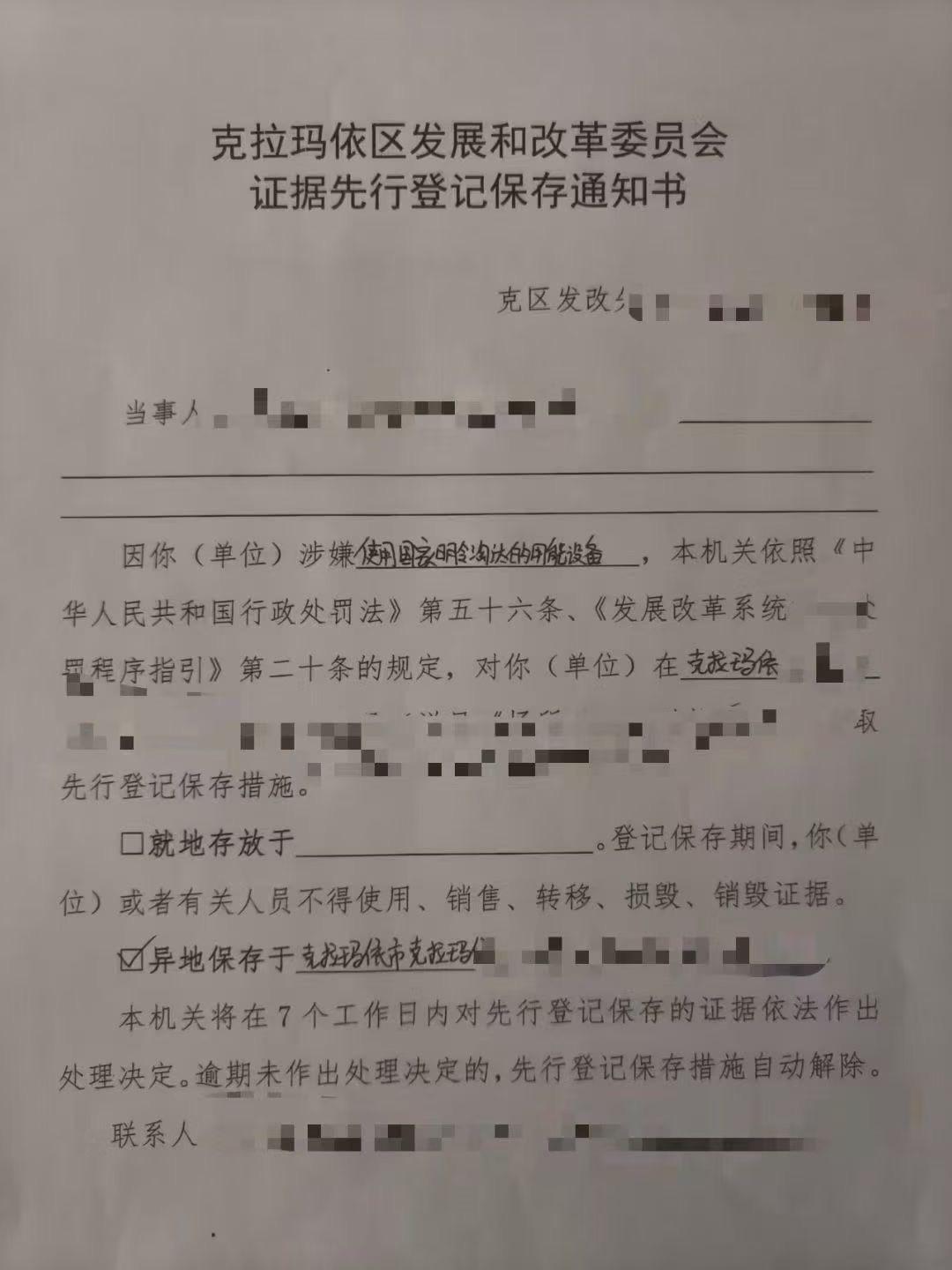

In China, the policy positioning of mining is not to encourage the industry, but rather to eliminate it as a necessary measure. The core requirements of the relevant departments' rectification documents are to strictly prohibit new additions, properly handle existing capacity, and promote an orderly exit, clearly listing virtual currency mining as an eliminated industry while emphasizing the need to accurately identify mining activities through abnormal electricity monitoring and park inspections, prohibiting mining under the guise of data centers.

From the perspective of practical governance measures, it resembles a combination of administrative and energy-side tactics: differential electricity prices or punitive electricity fees, cancellation of subsidies, cessation of financial support, and restrictions on electricity access and participation in the electricity market. Therefore, the direct consequences when many mining sites are dealt with often include power cuts, clearances, back payments for electricity, and cancellation of policy benefits—this is not the same as legal operation, but it does not equate to "mining itself necessarily violating criminal law."

What truly escalates the risk is usually the accompanying actions outside of mining: stealing electricity, illegal power supply, fraudulently claiming subsidies, obtaining support funds under the guise of supercomputing centers or data centers, illegal fundraising, money laundering channels, etc. Once these issues are triggered, the situation can quickly shift from industrial rectification to public security or criminal levels.

At the same time, financial regulation has maintained a tougher stance on virtual currency-related businesses, continuously emphasizing the crackdown on illegal activities related to virtual currencies and prioritizing anti-money laundering and cross-border capital risks. Viewing these two lines together helps to understand why such clearance actions occur repeatedly: mining has long been within the red line of rectification, and once the enforcement port is tightened, the power cut will happen faster than any announcement.

Why Was This Clearance So Intense?

The speed and intensity of the clearance often depend on two factors: whether the signals are unified and whether the enforcement measures are clear.

The coordination mechanism meeting led by the central bank at the end of November, involving multiple departments, was seen by the mining community as an important turning point. It did not release emotions but rather unified the enforcement standards: maintaining high pressure on virtual currency-related activities, strengthening the narrative around anti-money laundering and cross-border capital risks, and bringing topics like stablecoins into a stricter regulatory view. For the gray area industry, this means "the scope of scrutiny has expanded," and it also means that local systems know what to check next, how to check, who will lead, and who will cooperate.

At the same time, mining has long been treated within the framework of industrial policy in China, not just the financial regulatory framework. It is classified as an eliminated industry, with common governance methods including differential electricity prices, punitive electricity fees, park inspections, and abnormal electricity monitoring. The more realistic risk point is that simply running computing power may be treated as an eliminated industry, but once it involves stealing electricity, fraudulently claiming subsidies, or obtaining support funds under other project names, the nature shifts rapidly from gray to black, where accountability is possible.

Therefore, when the National Development and Reform Commission, energy, electricity, and park systems begin to coordinate, the clearance often presents a "sudden" feeling: it was still operational yesterday, and today it collectively shuts down. For the outside world, this is news; for miners, this is the power cut, and the power cut never requires prior announcement.

Why Did the Hash Rate Drop So Dramatically: Concentrated Power Cuts Amplify the Curve

The dramatic drop in hash rate is not primarily due to "digital fluctuations," but rather "concentrated power cuts." Since entering the ZH era, the network's hash rate has fluctuated daily, but most fluctuations resemble ocean waves: rising and falling, and looking back, they are merely noise. This time, it feels more like a beam being pulled out—there was a step-like drop in a short time, and the on-site information from the mining community consistently pointed to concentrated shutdowns in Xinjiang, which led the market to treat it as a hard event rather than normal fluctuations.

The key factor is structure. When the resurgence occurs in a concentrated form of "a few regions + a few parks + a few data centers," its advantage is rapid expansion, but its disadvantage is fragility: once the switch is pulled, it is not just a few scattered mining sites that drop, but a whole chunk of hash rate that becomes loose. In other words, the market is not debating whether the hash rate is an estimated value, but rather understanding one thing: what was cut off this time is likely a highly concentrated hash rate pool.

There is also an amplifying perception. The hash rate is calculated based on block generation speed: when large-scale shutdowns occur in a short time, the block generation interval becomes unstable, and short-term estimated values are more likely to show exaggerated peaks and troughs; as the difficulty adjusts in subsequent cycles, the curve will gradually smooth out. Therefore, this "scary-looking" drop is essentially an immediate projection of a regionally concentrated shutdown at the network level—it is not a false alarm, but rather an amplification effect brought about by concentration.

What Happens After the Clearance: Miners Suffer Most, the Market is Most Sensitive, and Hash Rate Will Continue to Migrate

The short-term impact will first hit miners' cash flow. Machines being confiscated or shut down means the payback period is instantly interrupted; custodians and electricity providers will be more cautious, and the costs of relocating, restarting, and finding new power sources will sharply increase. These costs will ultimately manifest in two ways: some miners will be forced to exit, while others will raise the risk premium, only willing to restart under higher return expectations.

At the market level, the most common saying is that miners will sell off their coins. This conclusion does not always hold directly: whether there is concentrated disposal, what the disposal path is, whether it enters the secondary market, and how long it will take all depend on the specific execution methods. However, the clearance will create a clear signal emotionally: the policy risk premium has returned. Especially in a phase of increased volatility, any news with a concentrated clearance color will be amplified, becoming a magnifier of price fluctuations.

In the medium term, the Bitcoin network will self-heal through difficulty adjustments: after the hash rate declines, block generation slows, followed by a difficulty reduction, improving short-term returns for the remaining miners, and the hash rate will regrow elsewhere. The protocol does not care whether it is in Xinjiang or Texas; it only cares about generating a block every ten minutes on average. But for Chinese miners, this means the next round of migration will be more dispersed, more hidden, and more socket-oriented.

The significance of this clearance in Xinjiang lies not in whether the lowest point is 836.75 or another number, but in that it has laid bare the true structure of the shadow resurgence: this is not a legitimate industrial recovery, but a gray area arbitrage driven by electricity, data centers, depreciation, and cash flow. Arbitrage is certainly quick, but when the switch falls, it is equally swift.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。