Original Title: "Underground Argentina: Jewish Moneylenders, Chinese Supermarkets, Laid-back Youth, and the Middle Class Falling into Poverty"

Original Author: Sleepy.txt, Dongcha Beating

In Argentina, even the dollar has failed.

Pablo's identity is somewhat special. Ten years ago, he was an employee of Huawei stationed in Argentina, living in this South American country for two years; ten years later, he returned to his old haunts as a Web3 developer to attend the Devconnect conference.

This perspective spanning a decade has made him a firsthand witness to a brutal economic experiment.

When he left back then, 1 dollar could only be exchanged for a dozen pesos; now, the black market exchange rate in Argentina has skyrocketed to 1:1400. According to the simplest business logic, this means that if you have dollars in your pocket, you should have king-like purchasing power in this country.

However, this "dollar superiority" lasted only until the first lunch.

"I specifically returned to the ordinary neighborhood where I used to live and found a small restaurant I used to frequent," Pablo recalled, "I ordered a bowl of noodles, and it surprisingly cost me 100 yuan when converted."

This was not a wealthy area crowded with tourists, but a "fly restaurant" filled with the hustle and bustle of daily life. Ten years ago, dining here cost an average of only 50 yuan; now, in this place defined by global media as a "failed country," prices have directly matched those of Shanghai's CBD or Paris in Western Europe.

This is a typical case of "stagflation." Although the peso has depreciated over 100 times, the prices of goods priced in dollars have actually risen by more than 50%.

When a country's credit completely collapses, inflation acts like an indiscriminate flood; even if you are sitting in the seemingly sturdy boat of dollars, the water level will still rise above your ankles. This country has magically transmitted the cost of currency collapse to everyone, including those holding hard currency.

Many people think that in such severe turmoil, people would panic and hoard dollars, or embrace cryptocurrencies as predicted by tech believers. But we were all wrong.

Here, young people neither save money nor buy houses, because the moment their salary arrives, its value begins to evaporate; here, the true control of financial lifelines is not the central bank, but a shadow financial network woven together by Jewish moneylenders in the Once district and over 10,000 Chinese supermarkets across Argentina.

Welcome to Underground Argentina.

Young People Dare Not Have a Future

To understand Argentina's underground economy, one must first grasp the survival logic of a group: those young people who "live for the moment."

If you walk the streets of Buenos Aires at night, you will experience a severe cognitive dissonance; the bars are bustling, the tango halls are filled with music all night long, and young people in restaurants are still generously tipping 10%. This does not seem like a crisis country undergoing "shock therapy," but rather like a prosperous era.

But this is not a symbol of prosperity; it is a nearly desperate "apocalyptic revelry." In the first half of 2024, the country's poverty rate soared to 52.9%; even after Milei's aggressive reforms, 31.6% of people were still struggling below the poverty line in the first quarter of 2025.

In the grand narrative of the Web3 circle, Argentina is often described as a "crypto utopia." Outsiders imagine that in this country where currency has failed, young people would go crazy buying USDT or Bitcoin as soon as they receive their salaries to hedge against risks.

But during his field visit, Pablo coldly burst this elite perspective bubble.

"This is actually a misconception," Pablo bluntly pointed out, "Most young people are typical 'moonlight' spenders; after paying rent, utilities, and daily expenses, there is hardly anything left to save for dollars or stablecoins."

It's not that they don't want to hedge against risks; it's that they don't have the means to do so.

What hinders savings is not just poverty, but also the "devaluation of labor."

From 2017 to 2023, the real wages of Argentinians fell by 37%. Even after Milei took office and nominal wages increased, the purchasing power of wages in the private sector still lost 14.7% in the past year.

What does this mean? It means that an Argentine young person is working harder this year than last year, but the bread and milk he can exchange for have decreased. In this environment, "saving" has become an absurd joke. Thus, a nearly rational "inflation immunity" has spread among this generation.

Since no matter how hard they work, they cannot save enough for a down payment on a house, and since the speed of saving will never catch up with the speed of currency evaporation, turning the pesos that could become worthless at any moment into immediate happiness has become the only economically rational choice.

A survey shows that 42% of Argentinians feel anxious all the time, and 40% feel exhausted. But at the same time, as many as 88% admit to combating this anxiety through "emotional spending."

This collective psychological contradiction is precisely a microcosm of the century-long ups and downs of this country; they dance the tango to fight against uncertainty about the future, numbing their deep-seated sense of powerlessness with barbecues and beer.

But this is just the surface of Underground Argentina; where do the billions of pesos cash that young people spend so wildly ultimately flow?

They have not disappeared. Under the cover of night in Buenos Aires, this cash flows like underground rivers, ultimately converging into the hands of two very special groups.

One is the largest "cash vacuum cleaner" in all of Argentina, and the other is the "underground central bank" that controls the lifeblood of the exchange rate.

Chinese Supermarkets and Jewish Moneylenders

If the Central Bank of Argentina suddenly announced a shutdown tomorrow, the country's financial system might fall into temporary chaos; but if those 13,000 Chinese supermarkets simultaneously closed, Argentina's social operation could immediately collapse.

In Buenos Aires, the real financial heart does not beat in the grand bank buildings, but is hidden in the cash registers on the streets and in the deep courtyards of the Once district.

This is a secret alliance formed by two groups of outsiders: one group is supermarket owners from China, and the other group consists of Jewish financiers who have been deeply rooted for a century.

In Argentina, nothing penetrates the fabric of the city more like "Supermercados Chinos (Chinese Supermarkets)." As of 2021, the number of Chinese supermarkets in Argentina has exceeded 13,000, accounting for more than 40% of the total number of supermarkets in the country. They may not be as large as Carrefour, but they are ubiquitous.

For Argentina's underground economy, these supermarkets are not just places to buy milk and bread; they are essentially "cash deposit points" that operate around the clock.

Most Chinese supermarkets try to encourage customers to pay in cash; some restaurants will remind you that using cash can enjoy discounts at checkout, and some even post notices: "Cash payment discount 10%–15%."

This is actually to avoid taxes. Argentina's consumption tax is as high as 21%, and to prevent the government from taking a cut of this cake, businesses are willing to offer discounts to consumers, just to keep massive sales revenue outside the official financial system.

"The tax bureau definitely knows, but has never strictly investigated," Pablo said in an interview.

A report from 2011 showed that at that time, the annual sales of thousands of Chinese supermarkets had already reached 5.98 billion dollars. Today, this number would only be larger. But there is a fatal problem: pesos are "hot potatoes," depreciating every second in an environment of triple-digit annual inflation.

"Chinese businesses earn a lot of cash in pesos and need to exchange it for yuan to return home, so they look for various ways to exchange money," Pablo said. "For Chinese tourists, the most convenient and best exchange rate channels are Chinese supermarkets or restaurants because they urgently need yuan to hedge against the pesos in their hands."

However, scattered tourists cannot consume such a massive amount of cash; Chinese supermarkets need another outlet, and in Buenos Aires, only the underground moneylenders represented by the Jews from the Once district have the capacity to absorb such a scale of cash.

"Historically, Jews gathered in a wholesale area called Once. If you've seen movies about Argentine Jews, some scenes are set in Once," Pablo explained. "There is a synagogue for Jews there, and it is also the only place in Argentina that has experienced a terrorist attack."

He was referring to the AMIA bombing on July 18, 1994.

On that day, a car loaded with explosives crashed into the AMIA Jewish community center, resulting in 85 deaths and over 300 injuries, marking one of the darkest pages in Argentine history. After that incident, a huge wall was erected outside the synagogue, covered with the word "Peace" in various languages.

This disaster completely changed the survival philosophy of the Jewish community. Since then, the entire community has become extremely closed and vigilant. These walls not only block bombs but also create an extremely introverted and highly united circle.

As time has passed, Jewish merchants have gradually exited the physical wholesale industry and turned to the field they are more skilled in—finance.

They operate underground moneylenders known as "Cueva (Cave)," utilizing their deep connections in politics and economics to build a capital flow network independent of the official system. Today, some have moved out of the Once district, and more diverse ethnic groups, including Chinese, have entered the underground moneylending business.

Under Argentina's long-standing foreign exchange controls, there was once a huge price difference of over 100% between the official exchange rate and the black market rate. This means that anyone who honestly exchanges currency through official channels would see their asset value evaporate by half in an instant. This forces both businesses and individuals to rely on the underground financial network built by the Jews.

Chinese supermarkets generate massive amounts of cash in pesos daily, urgently needing to exchange it for hard currency; Jewish moneylenders have dollar reserves and global capital transfer channels but need large amounts of cash in pesos to maintain daily high-interest loan turnover and exchange operations. The demands of both perfectly align, creating a perfect business loop.

Thus, in Argentina, dedicated cash transport vehicles (or a few inconspicuous private cars) shuttle daily between Chinese supermarkets and the Once district under the cover of night. The cash flow from the Chinese provides a continuous lifeblood for the Jewish financial network, while the Jewish dollar reserves offer the only escape route for Chinese wealth.

No cumbersome compliance checks are needed, no waiting in line at banks; relying on this cross-ethnic tacit understanding and trust, this system has operated efficiently for decades.

In that era when the national machinery malfunctioned, it was this non-compliant underground system that supported the most basic survival needs of countless ordinary families and businesses. Compared to the shaky official peso, Chinese supermarkets and Jewish moneylenders are clearly more trustworthy.

Point-to-Point Tax Evasion

If Chinese supermarkets and Jewish moneylenders are the arteries of Argentina's underground economy, then cryptocurrencies are the more secretive veins.

In recent years, a myth has circulated in the global Web3 community: Argentina is a sanctuary for cryptocurrencies. Data seems to support this— in this country of 46 million people, the cryptocurrency ownership rate is as high as 19.8%, ranking first in Latin America.

But when you delve into this land like Pablo, you will find that the truth behind the myth is not glamorous. There aren’t many people discussing the ideals of decentralization, nor are there many who care about the technological innovations of blockchain.

All the enthusiasm ultimately points to one bare verb: escape.

"Outside the crypto circle, ordinary Argentinians have a low understanding of crypto," Pablo said. For most Argentinians using cryptocurrencies, this is not a revolution about financial freedom; it is merely a self-defense battle about asset preservation. They do not care what Web3 is; they only care about one thing: can USDT prevent my money from losing value?

This explains why stablecoins account for 61.8% of Argentina's crypto trading volume. For freelancers, digital nomads, and the wealthy class with overseas businesses, USDT is their digital dollar.

Compared to hiding dollars under the mattress or risking black market exchanges, clicking a mouse to convert pesos into USDT seems more elegant and secure.

But safety is not the only consideration; a deeper motivation lies in concealment.

For the lower class, their "cryptocurrency" is cash.

Why do Chinese supermarkets prefer to accept cash? Because cash payments do not require invoices, directly saving 21% in taxes. For a working class earning only a few hundred dollars a month, this crumpled peso is their "tax haven." They do not need to understand blockchain; they just need to know that paying in cash can save them 15%.

For the middle class, freelancers, and digital nomads, stablecoins like USDT play the same role. The Argentine tax bureau cannot track on-chain transfers. A local Web3 practitioner described cryptocurrencies as a "digital Swiss bank." A programmer in Argentina receiving overseas projects, if paid through a bank, not only has to convert at the official rate but also pay high personal income taxes. But if they receive payment in USDT, that money becomes completely invisible.

This logic of "point-to-point tax evasion" runs through every class of Argentine society. Whether it is cash transactions by street vendors or USDT transfers by the elite, they are essentially expressions of distrust in national credit and a means of protecting private property. In a country with high taxes, low welfare, and continuously depreciating currency, every "gray transaction" is a rebellion against institutional plunder.

Pablo recommended a WebApp called Peanut, which can be used without downloading, has exchange rates close to black market prices, and even supports Chinese identity verification. This app is rapidly growing in Argentina. The popularity of such applications precisely proves the market's desire for an "escape route."

Although tools have become accessible, this Noah's Ark still only carries two types of people: the completely Underground (the cash-using poor and the crypto-using rich) and digital nomads with overseas income.

When the poor evade taxes with cash and the rich transfer assets with crypto, who becomes the only loser in this crisis?

The answer is heartbreaking: it is those law-abiding "honest people."

Compliance Suffocates the Honest

We usually think that having a decent job that pays taxes and is compliant is the ticket to the middle class. But in a country with a dual currency system and uncontrolled inflation, this "compliance ticket" has become a heavy shackle.

Their predicament stems from an unsolvable arithmetic problem: income is anchored to the official exchange rate, while expenses are anchored to the black market exchange rate.

Suppose you are an executive at a multinational company earning 1 million pesos a month. According to the official reports, at the official exchange rate of 1:1000, your monthly salary is equivalent to 1000 dollars. But in real life, when you go to the supermarket to buy milk or fill up your gas tank, all prices are priced based on the black market rate (1:1400 or even higher).

With this in and out, your actual purchasing power is halved the moment your salary arrives.

Worse still, you do not have the qualification to "disappear." You cannot offer cash discounts like the owners of Chinese supermarkets to evade taxes, nor can you receive payments in USDT like digital nomads to conceal assets. Every penny of your income is within the range of the tax bureau (AFIP), completely transparent, with nowhere to escape.

Thus, a cruel sociological phenomenon has emerged. From 2017 to 2023, a large number of "new poor (Nuevos Pobres)" have emerged in Argentina.

They were once respectable middle-class individuals, well-educated, living in decent neighborhoods. But as they were squeezed by rising living costs and depreciating incomes, they watched helplessly as they slid toward the poverty line.

This is a society of "reverse elimination." Those who navigate the underground economy—Chinese supermarket owners, Jewish moneylender operators, freelancers receiving USDT—have mastered the code for survival in the ruins. Meanwhile, those who try to "work well" within the official system become the ones paying the institutional costs.

Even the most astute individuals in this group find that all their efforts are merely defensive struggles.

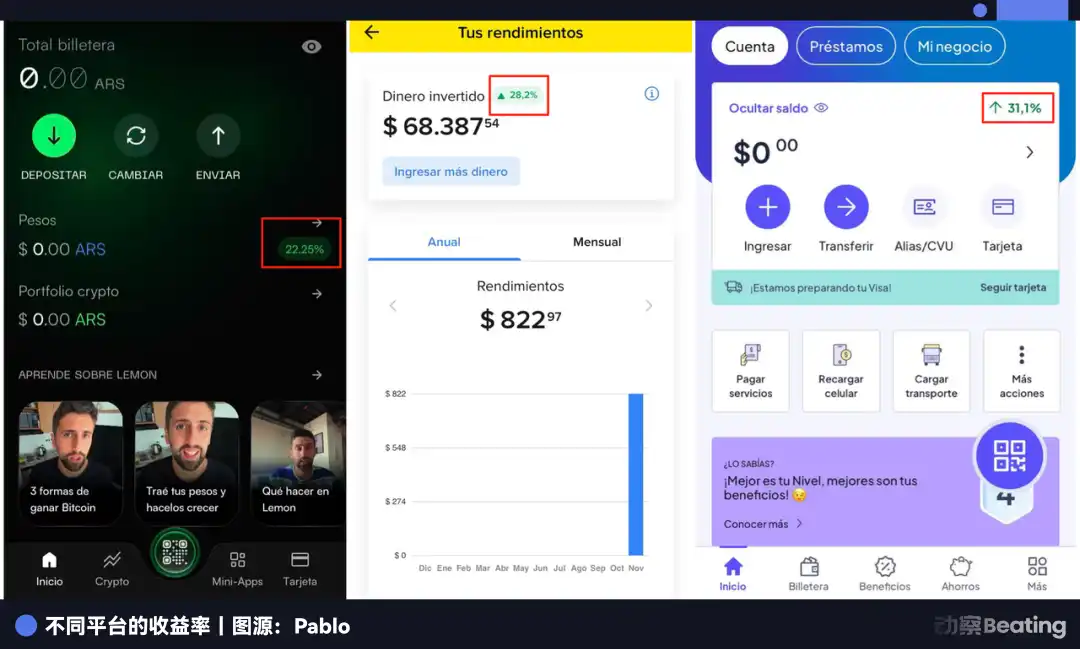

Pablo mentioned the "financial wisdom" of the Argentine middle class in the interview. For example, using platforms like Mercado Pago to achieve annualized returns of 30% to 50% for survival.

Sounds high? But Pablo did the math: "Considering the erosion of inflation on the exchange rate, such an APY can only maintain the dollar value of the pesos in their hands under stable exchange rates, but exchange rates are often unstable, and overall, such returns cannot keep up with the depreciation of the peso."

In addition, many savvy Argentinians will cash out through credit cards without considering the erosion before they sense a peso crash, then exchange it for dollars, taking advantage of the time difference in inflation for arbitrage.

But all of these are merely "defensive," not "offensive." In a country where currency credit has collapsed, all financial management and arbitrage attempts are essentially efforts to "not lose" or "lose less," rather than genuine wealth growth.

The collapse of the middle class is often silent.

They do not take to the streets to burn tires in protest like the lower class, nor do they emigrate directly like the wealthy. They simply cancel weekend gatherings, switch their children from private schools, and then anxiously calculate next month's bills late at night.

They are the most obedient taxpayers in this country and also the group that has been harvested the most thoroughly.

The Gamble of National Fortune

Pablo's return to Argentina revealed a microcosm of the country's shift in a socket in the corner.

Once, Argentina implemented an almost absurd trade protectionism, requiring all electrical appliances to meet "Argentinian standards," forcibly removing the top of universal triangular plugs, or else sales were prohibited. This was not just a plug issue; it symbolized mercantilist barriers, forcing citizens to pay for inferior and overpriced domestic industries through administrative orders.

Now, Milei is dismantling this wall. This "madman" president, who believes in the Austrian school, is wielding a chainsaw to conduct a social experiment that has drawn the world's attention: cutting government spending by 30% and lifting years-long foreign exchange controls.

With this cut, the effects were immediate. The treasury showed a surplus not seen in years, inflation rates fell from a crazy 200% to around 30%, and the once 100% gap between the official and black market exchange rates was compressed to about 10%.

However, the cost of reform is excruciating.

When subsidies are cut and exchange rates are freed, the new poor and moonlight class we mentioned earlier bear the first wave of impact. However, Pablo was surprised to find that despite the hardships, most of the people he encountered still support Milei.

Argentina's history is a cyclical tale of collapse and reconstruction. From 1860 to 1930, it was one of the richest countries in the world; but afterward, it fell into a long-term decline, oscillating between economic growth and crisis.

In 2015, Macri lifted foreign exchange controls in an attempt to liberalize reforms, ultimately failing and leading to the reimplementation of controls in 2019. Will Milei's reforms be the turning point to break this cycle? Or will it be yet another brief hope followed by deeper despair?

No one knows the answer. But it is certain that the underground world constructed by Jewish moneylenders, Chinese supermarkets, and countless individuals with "inflation immunity" possesses strong inertia and vitality. It provides shelter when the official order collapses and chooses to hibernate and adapt when the official order is rebuilt.

At the end of the article, let us return to Pablo's lunch.

"I initially thought the prices were so high that the waiter must be earning a lot, so I only tipped 5%, but later my friend educated me that I should still give a 10% tip," Pablo recalled.

In a country where prices are soaring and currency is collapsing, people still maintain the habit of tipping, still spin in tango halls, and still chat and laugh in cafes. This wild vitality is the true essence of this country.

For a hundred years, the Casa Rosada in Buenos Aires has changed hands time and again, and the peso has become worthless again and again. But the common people, relying on underground transactions and gray wisdom, have managed to find a way out in a dead end.

As long as this country’s desire for "stability" remains less than its yearning for "freedom"; as long as the public's trust in the government remains lower than their trust in the corner Chino, then Underground Argentina will always exist.

Welcome to Underground Argentina.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。