Written by: Lawyer Liu Honglin

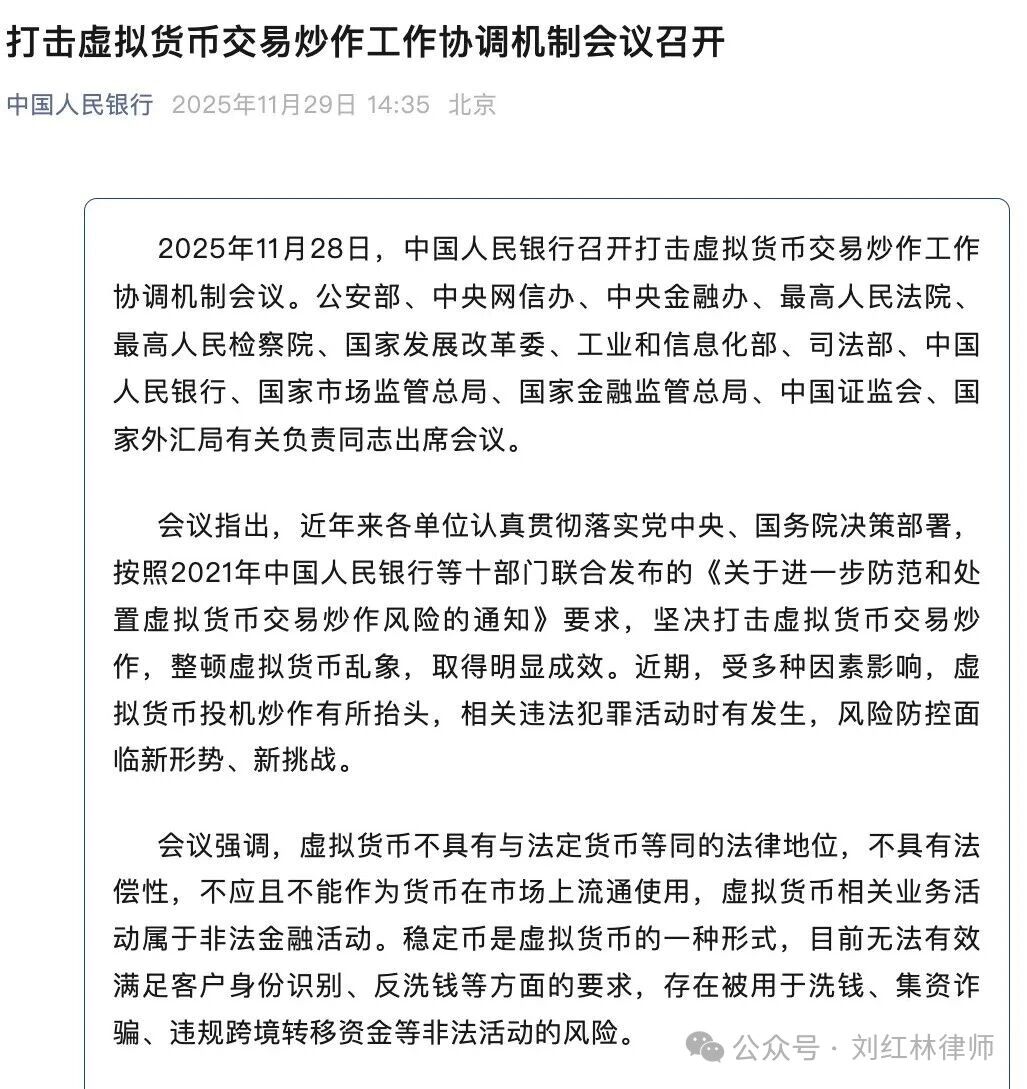

Recently, the meeting convened by the People's Bank of China to coordinate efforts in combating virtual currency trading speculation has sparked "explosive dissemination" within the industry. For those unfamiliar with domestic regulatory logic, it may seem like the state is once again implementing a "one-size-fits-all" approach to virtual currencies; however, for those who have been closely monitoring the domestic virtual asset governance system over the past decade, the content of this meeting is not only familiar but somewhat expected.

The reason is not hard to understand: the content of this meeting is not "new regulations," but rather a cross-departmental, systematic "reaffirmation of regulatory stance," publicly and clearly laying out the regulatory framework that has gradually formed over the past decade.

The so-called "strong regulatory signals" are essentially a correction to market misunderstandings.

To understand this meeting, one must return to the regulatory context from 2013 to 2021. China's governance of virtual currencies has never been vague; it has been clear, step-by-step, and progressively layered. In 2013, the People's Bank of China and five other ministries issued a notice on "Preventing Bitcoin Risks," which clearly stated for the first time that Bitcoin is not currency, does not have legal tender status, is not issued by the state, and does not possess monetary attributes. Therefore, it can only be regarded as a specific virtual commodity and should not be used as currency in the market. The document also required financial institutions and payment agencies to refrain from providing related services, marking the first "dam" in domestic regulation. In 2017, the People's Bank of China and seven ministries jointly issued a comprehensive ban on ICOs, classifying token issuance financing as illegal financial activity, and for the first time clearly defined behaviors such as "illegal token issuance" and "disguised public financing" as unlawful, demanding a complete withdrawal. By 2021, the People's Bank of China and ten departments issued a notice on "Further Preventing and Addressing Risks of Virtual Currency Trading Speculation," which further delineated the regulatory boundaries without ambiguity: all virtual currency-related activities are illegal financial activities; foreign exchanges providing services to domestic residents are also illegal; all activities related to the exchange, matching, clearing, and trading of fiat currency and virtual currency are prohibited. Pan Gongsheng also publicly stated that these policy documents remain effective and that the regulatory direction will not change.

In this context, looking at the three points discussed in this meeting: virtual currencies do not have legal tender status and should not be used as currency; virtual currency-related activities are illegal financial activities; stablecoins are a type of virtual currency that does not meet KYC, AML, and cross-border regulatory requirements. These points may seem unremarkable at face value, but the key lies in the timing of the meeting.

Currently, the industry cycle is warming up, on-chain activities are surging, and the demand for cross-border funds in foreign trade and among the public is increasingly shifting towards stablecoin pathways. Multiple countries around the world are embracing Web3 and laying out stablecoin legislation—against this backdrop, the regulatory choice to have the central bank lead, with participation from public security, internet information, the two high courts, the securities regulatory commission, and the foreign exchange bureau, to elevate existing regulatory language from "principle-based regulations" to "public signals" is essentially aimed at preventing market misinterpretation of policies and avoiding entrepreneurs stepping on the line under erroneous premises.

In fact, China's legal framework for virtual currencies has formed a very clear and stable three-tier structure in recent years: civil justice recognizes the property attributes of virtual currencies, administrative regulation comprehensively prohibits virtual currency financial activities, and criminal justice strictly evaluates the role of virtual currencies in illegal financial chains. These three layers are not contradictory but represent a division of institutional labor. For example, in a civil judgment from a grassroots court in Shanghai, Bitcoin was recognized as virtual property in the sense of civil law and could be returned as an object of restitution, reflecting the protection of property rights under civil law. However, in another case of illegal currency exchange involving virtual currencies published by the Shanghai Pudong Court, the parties used domestic shell company accounts to provide stablecoin cross-border transfers for unspecified clients, with a transaction scale reaching 6.5 billion yuan. The court determined this as engaging in illegal financial activities using virtual currencies, constituting a crime, reflecting the criminal law's evaluation of the harmfulness of the behavior. The administrative level is similar; companies that disguise token sales as "digital asset investment training" or mask agency clearing activities under the guise of "blockchain technology service fees" have frequently faced administrative penalties.

Civil law protects "virtual property rights," administrative law prohibits "financial transaction activities," and criminal law targets "criminal financial chains," together forming the current regulatory reality regarding virtual currencies in mainland China. The public often only sees one layer; for instance, seeing the court recognize the property attributes of virtual currencies may lead to the misconception that policies are loosening. Similarly, observing Hong Kong's push for stablecoin regulatory rules may lead to the assumption that mainland China will follow suit. When news reports emerge about criminal cases involving cryptocurrencies, there is often a knee-jerk reaction that policies are tightening. One of the significant meanings of this meeting is to reposition these three layers of logic: virtual currencies "as property" can be protected, but "as financial activities" cannot occur; judicial processes can return assets, but administrative regulation remains prohibitive; blockchain technology can exist, but financial activities involving virtual currencies cannot be implemented in mainland China.

The meeting specifically named stablecoins, leading outsiders to believe in a "regulatory upgrade." However, in reality, the regulatory stance has never changed; it is merely a response to cool down the currently overheated market. Over the past three years, stablecoins have become the "settlement layer" of the on-chain economy, with cross-border payments, on-chain finance, gray channels, and even some real trade payments heavily relying on stablecoins like USDT and USDC. This means that stablecoins effectively constitute a "shadow settlement network"—capable of moving value across borders without going through the national sovereign financial system or entering the interbank payment and settlement system, and not falling within the regulatory radius of foreign exchange statistics, cross-border fund reporting systems, or anti-money laundering frameworks. Against the backdrop of strict capital controls in China, the real concern for regulators is not whether "stablecoin reserves are sufficient," but rather that they inherently bypass the state's core macro-financial regulatory capabilities.

From a governance logic perspective, the government's regulatory focus has never been on "what the asset is," but rather on "where the funds are flowing and whether regulation can reach them." Under this logic, stablecoins, as a cross-border, instant, anonymous, divisible, and highly liquid value transfer tool, are essentially an unlicensed cross-border settlement facility. Even with technological innovations, there is no possibility of having pilot space within China. The reaffirmation of stablecoins in this meeting aims to prevent new misunderstandings from arising in the current heated market, making it clear to the public: financial activities involving stablecoins have no exceptions in mainland China, no gray areas, and no room for discussion.

Many entrepreneurs are therefore concerned: will this reaffirmation of regulation in mainland China affect Hong Kong's ongoing digital asset development strategy? Our judgment is: it will not. On the contrary, it will make Hong Kong's institutional advantages more apparent and its commercial development space more solid.

In recent years, Hong Kong has established a very clear institutional framework: a VASP licensing mechanism based on the "Anti-Money Laundering Ordinance," a regulatory system for virtual asset trading platforms, and a regulatory framework for stablecoin issuers. Particularly in stablecoin regulation, Hong Kong requires issuers to maintain 100% reserves, with reserve assets needing to be periodically disclosed through licensed auditing firms, and issuers must meet minimum registered capital requirements and be included in the AML regulatory framework. This system is not "laissez-faire innovation," but rather "strict yet feasible." It aligns with the same logical framework as the currently most stringent stablecoin legislation being discussed in Singapore, the European Union, and the United States.

More importantly, the regulatory positioning of Hong Kong is not in opposition to that of mainland China, but rather represents a "institutional functional division of labor." Mainland China is responsible for risk isolation, preventing virtual currencies from impacting financial stability and cross-border fund security; Hong Kong is responsible for accommodating global virtual asset innovation and providing institutional grounding for China's voice in international digital asset rules. If the mainland's stance is vague and its attitude unclear, Hong Kong's institutional space may be disrupted, even misinterpreted as "a pilot area for the mainland." Now that the boundaries are drawn more clearly, Hong Kong can more focusedly promote institutional innovation.

From a higher-dimensional perspective, China's governance of virtual assets is neither "completely prohibitive" nor "partially open," but rather a governance model of "dual-track parallelism, clear boundaries, and complementary functions." The core goal of the mainland is controllable funds, manageable risks, and regulatory oversight of cross-border activities; Hong Kong's task is to establish an innovative space that is regulatory, auditable, and accountable. In such a structure, the clearer the boundaries, the safer the innovation; the clearer the stance, the less likely the industry is to misjudge.

Therefore, returning to the meeting itself: it did not bring any new regulatory measures, but precisely because there was "no new content," it allowed the industry to return to a trajectory of understanding that is closer to the essence of regulation. It closed the fantasy of "the mainland possibly loosening" and ended the speculation of "whether stablecoins are exceptions," further undermining the basis for the conjecture of "whether the mainland is quietly paving the way." For regulation, ambiguity is not space; clarity is space; for the industry, uncertainty is the greatest risk.

For all market participants engaged in virtual asset investment and trading, stablecoin issuance, Web3 payments, on-chain financial innovation, and RWA business development, the signals brought by this meeting are exceptionally clear: abandon the fantasy of conducting virtual currency-related activities in mainland China and embrace the established encouragement for innovation and Web3 commercial implementation in Hong Kong.

Choosing the right direction leads to twice the result with half the effort. From the broader perspective of entrepreneurial strategic choices, this reaffirmation of regulatory attitude in the mainland, aimed at avoiding market misunderstandings, is not necessarily a bad thing for entrepreneurs in China's Web3 industry.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。