Original Author: Sleepy.txt

December 1, 2025, Phnom Penh.

The wind by the Mekong River remains humid and hot, but for the hundreds of thousands of Chinese people living here, this winter is much colder than in previous years.

This day is destined to be etched into the collective memory of Chinese merchants in Cambodia.

In the early morning, on Sihanouk Boulevard. The financial totem once regarded as "never sleeping" — the headquarters of Huibang, has lost its heartbeat overnight. The roaring sound of cash trucks coming and going has vanished, replaced by a cold "Withdrawal Suspension Notice" posted on the glass door, and the hundreds of Eastern faces outside the gate, gradually stiffening in fear.

History always rhymes with the same verses. This scene evokes a hazy memory of the night before the collapse of the gold yuan in Shanghai in 1948, or the financial street in Beijing during the P2P explosion in 2018.

The collapse did not come without warning. In the 48 days and nights leading up to this, rumors about the impending downfall of this financial giant, dubbed "Cambodia's Alipay," had already spread like a plague among underground money changers and Telegram groups in Phnom Penh. From the joint sanctions by the US and UK against the Prince Group, to the seizure of $15 billion in crypto assets, to the halving of the black market price of the stablecoin USDH issued by Huibang, all signals pointed to the same conclusion — liquidity exhaustion.

The suspension of Huibang is not just the sudden death of a company, but the curtain call of a distorted commercial era.

In the past tumultuous six years, it has been the core capillary of Cambodia's underground economy. It connected the casinos in Phnom Penh, the parks in Sihanoukville, and even the scam terminals across the ocean, constructing an offshore financial island seemingly impervious to the SWIFT system.

Its downfall not only locked the fortunes and lives of tens of thousands of Chinese merchants but also declared the complete bankruptcy of the "grassroots logic."

The illusion that one could ignore the rules by relying on technological dividends, or that one could evade the hunter's gun by hiding in the jungle, finally collided heavily with the iron plate of geopolitical and compliance regulation.

This is a delayed reckoning, and a bloody coming-of-age ceremony that the generation of Chinese internet grassroots venturing abroad had to undergo.

The Lost Paradise of Tech Elites

If we review the rise of Huibang, we will find that its starting point was not evil, but an extreme worship of efficiency.

Turning the clock back to 2019. That year, the traffic dividend of China's internet peaked, and the game of stock began; "going abroad" became the grand narrative for elites from major companies seeking new lands. A group of mid-level tech and product managers from large firms, armed with the most advanced code architecture and the vision of inclusive finance, landed at Phnom Penh Airport.

At that time, Cambodia's financial ecosystem was still in the Jurassic era.

Bank branches were scarce, efficiency was low, and foreign exchange controls were strict. For the hundreds of thousands of Chinese merchants engaged in trade, catering, and construction in Phnom Penh, the flow of funds was a nightmare. They either risked carrying heavy cash in US dollars on the streets or endured the exorbitant rates of underground money changers.

This backwardness, in the eyes of internet people accustomed to scanning for payments, was not just a pain point but a vast expanse of traffic and a huge gap.

Using China's mature mobile payment technology to launch a "dimensionality reduction strike" on Cambodia's traditional finance became the unspoken action program of that generation of overseas elites.

They indeed achieved it, and did it beautifully. From the moment Huibang Payment went live, it conquered the market with a kind of "violent aesthetics" convenience: a fully Chinese interface, 24/7 online customer service, and instant transactions, it replicated the silky experience of Alipay at the pixel level.

But the real killer was its extremely low entry threshold. In this country, which originally required layers of review, Huibang did not need cumbersome identity verification or tax proof; as long as one had a phone number, funds could flow freely in Phnom Penh's underground network.

This approach achieved tremendous commercial success. In just two years, Huibang penetrated every aspect of Chinese life in Phnom Penh, from buying a cup of milk tea to paying for construction projects, becoming the de facto "Chinese central bank" of Cambodia.

However, the neutrality of technology is often the biggest lie in the modern business world.

When this group of product managers, who believed in "user experience first," ran wildly in the lawless soil of Phnom Penh, they quickly collided with a temptation unimaginable domestically — the overwhelming wave of black and gray industries.

In the compliant business world, the core barrier for payment institutions is risk control; but in Phnom Penh, the most profitable clients are gambling groups and telecom fraud parks, and what they need most is precisely "no risk control."

For these behemoths, the fee rate is not important; what matters is concealment and safety. They do not need a compliant e-wallet but an underground river that can instantly launder hundreds of millions of dollars in dirty money.

This is a classic ethical dilemma in business: when the growing KPI clashes with the compliance bottom line, to whom should technology bow?

Huibang chose to bow to growth.

They began to "optimize" the money laundering process with internet thinking. To retain these top clients, they actively removed facial recognition and relaxed transfer limits. In their logic, this was still "serving users" and "solving pain points." They used "technology is innocent" to self-hypnotize, believing they were merely building roads, and whether the vehicles running on those roads were carrying goods or dirty money was irrelevant to the road builders.

It was this alienation of "technological tool rationality" that transformed Huibang from a convenient payment tool into Southeast Asia's largest money laundering hub.

They thought they were the Jack Ma of Phnom Penh, changing business with technology; little did they know, in the jungle lacking regulatory constraints, they ultimately became the Du Yuesheng by the Mekong River.

But this was just the beginning of their downfall. Once the payment channels were opened, this group of smart people discovered another more lucrative and darker track — introducing the "e-commerce escrow transaction" model into the human trafficking chain.

The Sinful SKU

In all internet business textbooks, the "platform model" is regarded as the ultimate evolution of commerce. Once Huibang connected the underlying infrastructure of payment, its ambition naturally extended to the transaction phase.

In the jungle of Phnom Penh, filled with fraud and violence, the most scarce resource is not US dollars or heads, but "trust."

This is a typical dark forest, where snakeheads collect money without delivering people, parks take people without paying, and money laundering intermediaries abscond with funds. The high risks of black eating black greatly hinder the transaction efficiency of the black industry.

For those product managers, this was not evil; it was clearly an excellent "trust mechanism optimization scenario."

In 2021, "Huibang Escrow" emerged.

Its product logic was a perfect replica of Taobao; buyers (fraud parks) entrusted funds to the platform, sellers (human traffickers) delivered goods, and once the buyers confirmed receipt after inspection, the platform released the funds and took a commission.

This mechanism, used in Hangzhou to reassure consumers buying dresses, was employed in Sihanoukville to buy and sell "front-end developers."

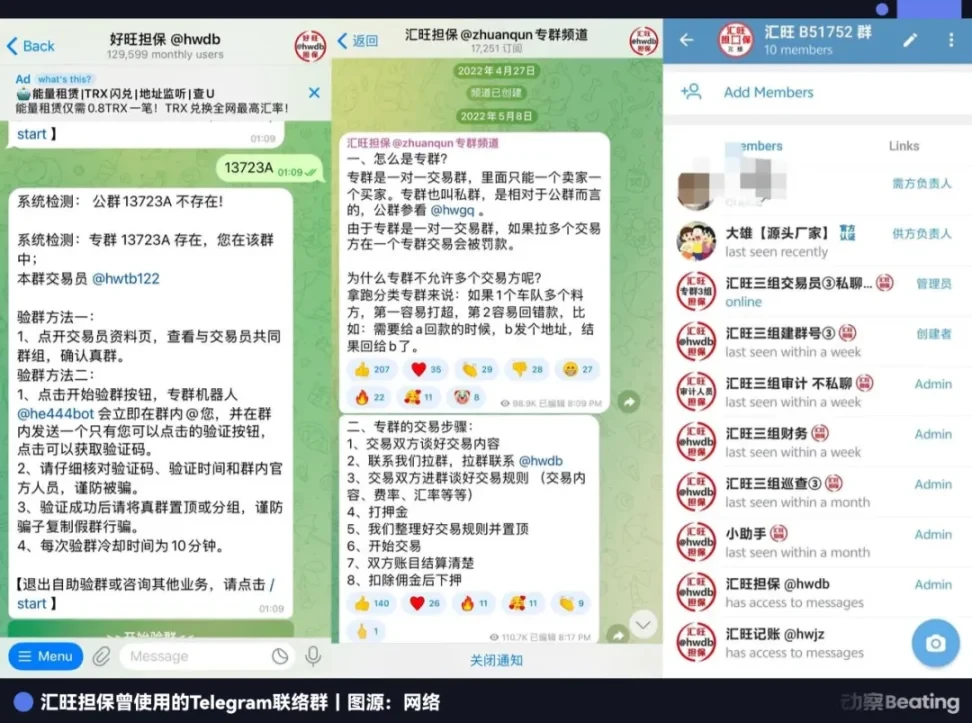

In the thousands of active Telegram groups of Huibang Escrow, people were completely objectified into cold SKUs.

Every supply and demand message in the group was meticulously standardized and packaged, resembling a Double Eleven product detail page:

"Proficient in Java, two years of experience in a large company, obedient, passport in hand, fixed price of 20,000 U."

"Looking to purchase: a team for promoting European and American markets, with resources, price negotiable, can go through escrow."

For the technicians maintaining the system in air-conditioned rooms, this was just lines of code and data. They did not need to see how those referred to as "goods" were stuffed into vans, nor did they need to hear the screams under electric batons; they only needed to focus on the order volume and the continuously rising GMV in the backend.

According to data from blockchain analysis company Elliptic, since 2021, the platform has completed transactions worth at least $24 billion through cryptocurrency. This is not just a number; it is the sum of countless individual fates converted into chips.

Even more chilling was the frenzied iteration of product functions.

To meet the parks' demand for capturing runaways, Huibang Escrow even derived a "bounty" service.

In those secret groups, violence was no longer an uncontrollable barbaric act but a value-added service that could be ordered with a click: "Capture a runaway programmer, bounty 50,000 USDT; provide effective location, bounty 10,000 USDT."

This reckless expansion ultimately attracted the attention of hunters. In February 2025, under pressure from the FBI, Telegram banned the main channel of Huibang Escrow. This should have been a devastating blow, but the resilience of the black industry exceeded everyone's imagination.

Just a week later, hundreds of thousands of users seamlessly migrated to another chat software called Potato Chat through backup links.

Telegram is known in the circle as "paper airplane," while Potato Chat is referred to as "potato." Compared to the airplane flying in the sky, the potato is buried deep underground, more secretive and harder to be locked onto by regulatory radars.

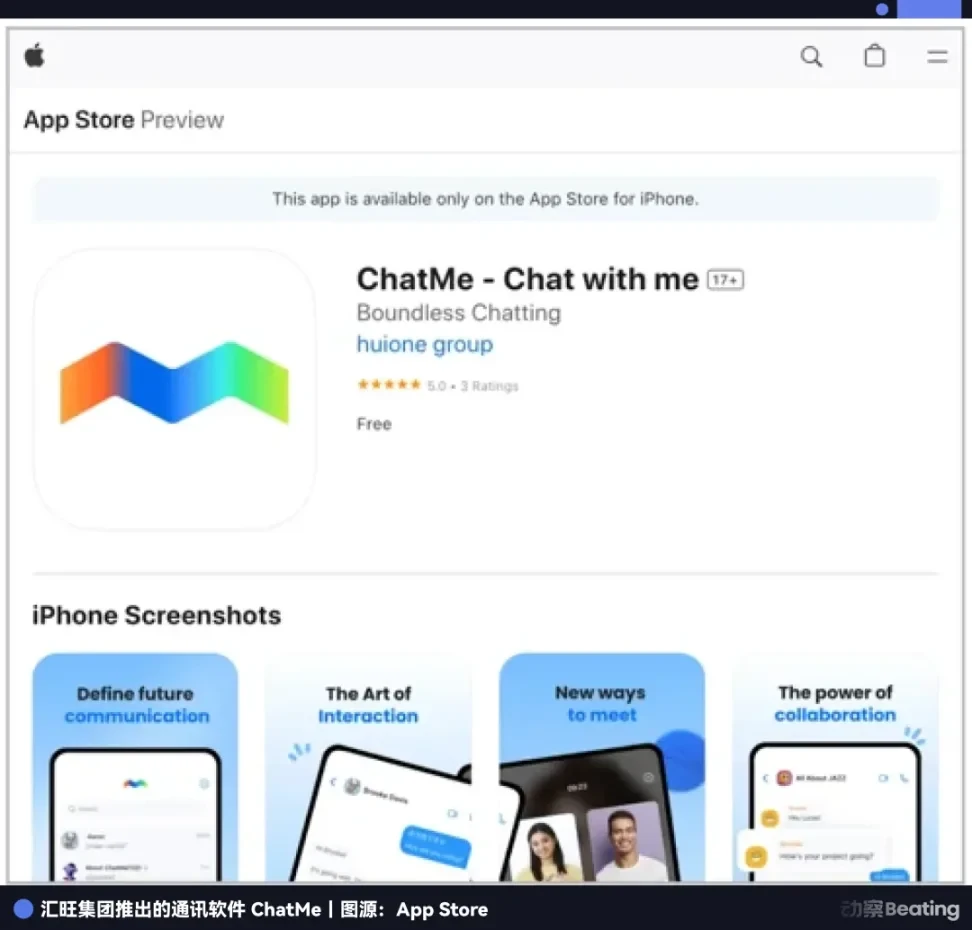

In this great migration, Huibang Group was not only the promoter but also the behind-the-scenes operator. They not only invested in "Potato," achieving a shell rebirth of their business, but even developed an independent communication software called ChatMe, attempting to build a completely closed, self-sufficient digital dark kingdom.

This guerrilla tactic of having multiple escape routes is not only a mockery of regulation but also a deep-seated arrogance.

They firmly believed that as long as the code was written fast enough, they could outrun the law; as long as the servers were hidden deep enough, they could create a lawless land independent of real-world rules. But they forgot that the servers of the dark web ultimately need to be powered.

While they were busy changing their identities in the virtual world, in the real world, an iron net targeting the funding chain was quietly tightening.

Symbiotic Model

In the chess game of finance, the highest power is never about how many chips one has, but about having the power to define the chips.

The operators of Huibang keenly realized that no matter how many identities they changed, as long as they continued to use USDT, their throats would always be held in the hands of Americans across the ocean, because Tether could cooperate with the FBI at any time to freeze on-chain assets with a single click.

Thus, they decided to establish their own Federal Reserve by the Mekong River.

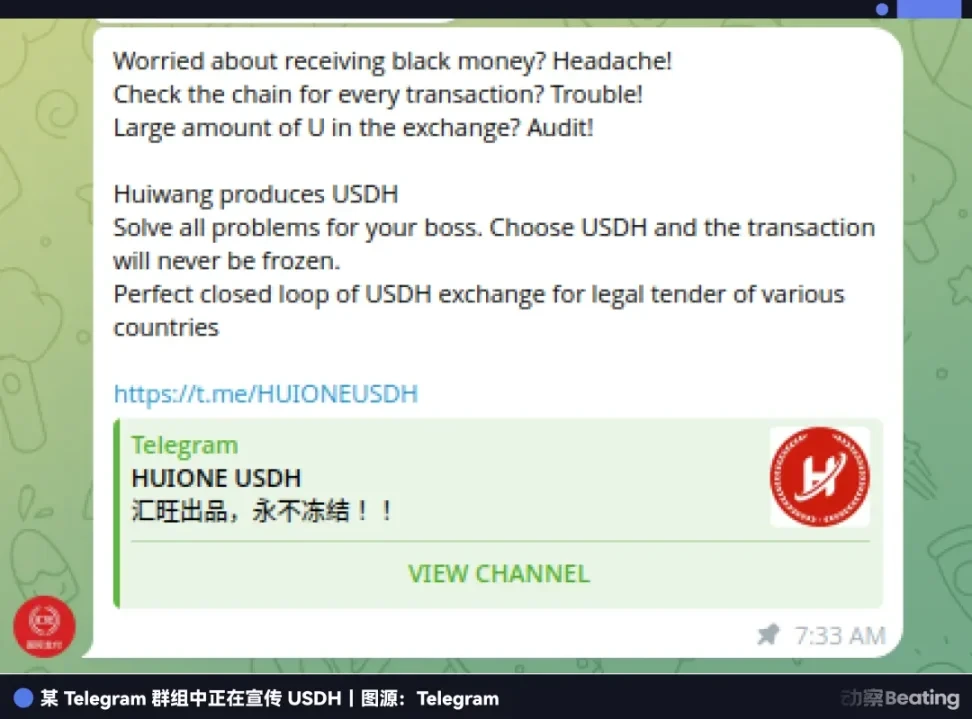

In September 2024, Huibang officially issued the stablecoin USDH.

In the official propaganda filled with incitement, the core selling point of USDH was starkly defined as "assets cannot be frozen" and "not subject to traditional regulatory constraints." This was essentially a rallying call to the global black market — here, there is no FBI, no anti-money laundering laws; this is an absolutely free financial utopia.

To promote this digital IOU issued by a private company, Huibang launched a financial product that would make Wall Street blush — deposit USDH with an annual yield of 18%, and a total return of 27% upon maturity.

Thus, an incredibly ironic scene unfolded. Those scammers who had been crazily harvesting profits worldwide, lured by the high interest of 18%, ultimately deposited the ill-gotten gains they had painstakingly obtained back into Huibang's fund pool.

In Phnom Penh's underground world, those self-proclaimed clever pig-butchers failed to realize that in the face of Huibang's larger pig-butchering operation, they themselves had become the "pigs" waiting to be slaughtered.

Where does this "independent nation-building" arrogance come from?

If we look at the board of directors of Huibang Payment, a prominent name stands out: Hun To.

What does this name mean in Cambodia? He is the nephew of former Prime Minister Hun Sen and the cousin of current Prime Minister Hun Manet. According to the U.S. Treasury's sanctions report, this figure, who navigates the core of power in Phnom Penh, is not only a director of Huibang but also the umbilical cord connecting the company to Cambodia's highest authority.

This is the most secretive "symbiotic model" in Southeast Asia's black market.

The Chinese team is responsible for exporting technology; they build payment systems with large company code, manage human trafficking with e-commerce logic, and evade regulation with blockchain technology; local elites are responsible for exporting licenses; they provide legitimate banking licenses, tacitly allow parks to build barbed walls, and even let the police turn a deaf ear to cries for help from within those walls.

Technology provides efficiency, and power provides security. It is precisely because of this highest-level "umbrella" that they dare to offer bounties for capturing people in broad daylight and issue private currencies that challenge the dollar's hegemony. For them, the law is not an untouchable red line but a commodity that can be bulk-purchased through the exchange of interests.

This naked exchange of interests often wears a warm and charitable facade.

In Cambodian Chinese newspapers, you often see scenes like this: Huibang executives draped in sashes receiving honorary certificates from the Red Cross from the hands of the powerful, donating large sums to impoverished schools, their faces beaming with compassionate smiles.

At the same time, in the Huibang Escrow group, bloody money laundering transactions are frantically scrolling through the screen.

In the morning, it is a den of evil transactions; in the afternoon, it is a charitable gala of compassion.

This extreme sense of division is not hypocrisy but a necessity for survival. Just as Du Yuesheng established his status as a "social dignitary" in Shanghai by running schools and maintaining public order, along the Mekong River, "charity" is a special tax paid to the core of power, a bleaching agent for laundering identities, and the lubricant that keeps this vast symbiotic entity running.

This carefully woven web of political and business relationships had brought Huibang years of security. They once thought that as long as they secured relationships in Phnom Penh, they could navigate the edges of the rule of law.

Until October 2025, when a butterfly flapped its wings from across the ocean.

The storm of sanctions that began in Washington not only overturned the seemingly indestructible umbrella but also directly shattered the fragile foundation of this "shadow central bank."

When Grassroots Wisdom Collides with the Financial Iron Curtain

In the traditional logic of the economy in Chinese county towns, there are usually two ways to solve problems: one is to find connections, and the other is to change identities.

When the crisis first emerged, the operators of Huibang attempted to employ old tricks. Even after their banking license was revoked in March 2025, they naively tried to create a smokescreen by renaming themselves "H-Pay" and claiming to "expand into Japan and Canada."

In their cognitive inertia, as long as the panda statue in Phnom Penh still stood, and as long as the Hun family shares remained, this was just another small problem that could be smoothed over with money.

But this time, their opponent was no longer the local police accepting tips but the heavily armed American national machine.

On October 14, 2025, a massive black swan descended. The U.S. Department of Justice announced the seizure of $15 billion in cryptocurrency belonging to Chen Zhiming of the Prince Group.

This was a number that suffocated all of Southeast Asia. To put it in perspective, Cambodia's GDP in 2024 was only about $46 billion. This was not just an asset seizure; it was equivalent to directly draining one-third of this country's underground economy.

For Huibang, the Prince Group was not only its largest client but also the source of its liquidity. With the source dried up, the downstream was doomed.

What made them feel even more desperate was the dimensionality of the crackdown.

For a long time, the black market had an almost superstitious misunderstanding of USDT, believing it to be "decentralized" and not subject to legal regulation. However, USDT is actually highly centralized; although the FBI cannot directly command Tether, as a commercial entity eager to integrate into the mainstream financial system, Tether must strictly comply with the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions list.

When U.S. regulatory agencies issued a long-arm jurisdiction ban, there was no need for SWAT teams to break down doors or for lengthy transnational lawsuits; Tether's backend would freeze the relevant addresses. Hundreds of millions of dollars on the blockchain instantly turned into non-transferable "dead money."

This was a form of warfare they had never understood. This group of smart people, who had thrived on "finding loopholes," had spent their lives best at punching holes in walls, but this time, their opponent directly tore down the load-bearing wall.

In the dust of the collapsing building, the first to suffocate are always the lowly ants at the bottom.

At the end of Huibang's ecological chain, there exists a large group — the cash exchangers. In Phnom Penh, they are the human cash trucks delivering U.S. dollars on motorcycles; in mainland China, they are the score groups operating transfers hidden in rental apartments. They earn a meager exchange rate of 0.3% but bear the highest risks in the entire system.

In the past, they were the most sensitive nerve endings of Huibang's machine; now, they have become the most direct cannon fodder in the card-cutting operation.

In the Telegram "Frozen Friends Group," thousands of desperate pleas for help flood in every day; all their bank cards have been frozen, they have been placed on fraud-related punishment lists, and they cannot even take high-speed trains or flights, facing the risk of arrest upon returning home.

Once a cash cow, the fleet has now become a high-risk cage. They hold unsellable USDH, their domestic accounts are frozen, and they are trapped in a foreign land.

A Generation's Funeral

When the glass door of Huibang's headquarters was posted with a notice, it was not just a company that fell but an era.

It was an elegy for the "grassroots venturing abroad" era of Chinese internet, a historical footnote filled with fantasies and ambitions.

In that specific time window, a portion of overseas entrepreneurs entered the jungles of Southeast Asia with a "giant baby mentality." They wanted both the exorbitant profits and freedom of lawless lands and the rules and safety of the civilized world; they only believed in connections and technology, but had no respect for the law.

They thought technology was a neutral tool, unaware that if tools are in the hands of those without bottom lines, they can become instruments of evil; they thought globalization was escaping from one cage to the wilderness, not realizing that globalization is moving from one set of rules to another, more stringent set of rules.

The rise and fall of Huibang is a modern fable about the "banality of evil."

Initially, they just wanted to create a useful payment tool to solve the pain of currency exchange; later, to achieve growth, they became accomplices of the gray market; and eventually, for the sake of exorbitant profits, they became the architects and participants of evil.

The moment a person decides to establish order for evil, they are destined to be unable to turn back.

Years later, when a new generation of entrepreneurs sits in the newly renovated office buildings of Phnom Penh, sipping Starbucks while discussing ESG and compliance listings, perhaps no one will remember how many bytes of evil once flowed through the underground cables of this city.

Nor will anyone remember how many self-righteous "Du Yueshengs" were buried in the night by the Mekong River.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。