Author: Ray Dalio

Translation: Block unicorn

Although I remain an active investor with a passion for investing, at this stage of my life, I am also a teacher, striving to impart the principles I have learned about how reality works and how to navigate it to others. Having been involved in global macro investing for over 50 years and drawing many lessons from history, the content I teach is naturally closely related to this.

This article will cover:

The most important distinction between wealth and money, and

How this distinction drives bubbles and crashes, and

How this dynamic, accompanied by significant wealth disparities, can burst bubbles, leading to crashes that are destructive not only financially but also socially and politically.

Understanding the difference between wealth and money, as well as their relationship, is crucial, particularly: 1) how bubbles form when financial wealth becomes very large relative to the amount of money; 2) how bubbles burst when the need for money leads to the sale of wealth to obtain money.

This very basic and easy-to-understand concept about how things operate is not widely understood, but it has helped me greatly in my investment career.

The key principles to grasp are:

Financial wealth can be created very easily, but that does not represent its true value;

Financial wealth only has value when it is converted into consumable money;

Converting financial wealth into consumable money requires selling it (or collecting its returns), which often leads to the bursting of bubbles.

Regarding the statement "financial wealth can be created very easily, but that does not represent its true value," for example, if a founder of a startup sells shares of the company—let's say worth $50 million—and values the company at $1 billion, then this seller becomes a billionaire. This is because the company is valued at $1 billion, while in reality, the actual wealth of the company is far from reaching $1 billion. Similarly, if a buyer of a publicly traded company purchases a small amount of shares from a seller at a specific price, the valuation of all shares will be based on that price, thus determining the total wealth of the company through the valuation of all shares. Of course, the actual value of these companies may not be as high as these valuations suggest, as the value of assets depends on their selling price.

As for the point that "financial wealth is essentially worthless unless converted into money," this is because wealth cannot be spent, while money can.

When wealth becomes very large relative to the amount of money, and those who possess wealth need to sell it to obtain money, the third principle applies: "Converting financial wealth into consumable money requires selling it (or collecting its returns), which often leads to the bursting of bubbles."

If you understand these things, you will be able to grasp how bubbles form and how they burst, which will help you predict and respond to bubbles and crashes.

It is also important to note that while both money and credit can be used to purchase things, a) money is the means of final settlement for transactions, while credit incurs debt that needs to be funded in the future to repay the transaction; b) credit is easy to create, while money can only be created by central banks. People may think that purchasing things requires money, but this idea is not entirely correct, as people can also buy things with credit, which generates debt that needs to be repaid. Bubbles often arise from this.

Now, let's look at an example.

While the mechanisms of all bubbles and crashes throughout history are essentially the same, I will use the bubble of 1927-1929 and the crash of 1929-1933 as an example. If you think about how the bubble of the late 1920s, the crash of 1929-1933, and the Great Depression occurred from a mechanistic perspective, as well as the measures taken by President Roosevelt in March 1933 to alleviate the crash, you will understand how the principles I just described come into play.

What funds drove the stock market's surge and ultimately formed the bubble? And where did the bubble originate? Common sense tells us that if the money supply is limited and everything must be purchased with money, then buying anything means reallocating funds from other things. Due to sell-offs, the prices of the reallocated goods may fall, while the prices of the purchased goods will rise. However, at that time (for example, in the late 1920s) and now, the surge in the stock market was not driven by money, but by credit. Credit can be created without money and is used to purchase stocks and other assets that constitute the bubble. The mechanism at that time (also the most classic mechanism) was that people created and borrowed credit to buy stocks, thereby incurring debt that needed to be repaid. When the funds needed to repay the debt exceeded the funds generated by the stocks, financial assets had to be sold, leading to price declines. The process of bubble formation, in turn, led to the bursting of the bubble.

The general principles driving the dynamics of bubbles and crashes are:

When the purchase of financial assets is funded by a large expansion of credit, and the total wealth rises significantly relative to the total amount of money (i.e., wealth far exceeds money), a bubble forms; and when wealth needs to be sold to obtain funds, a crash is triggered. For example, during the period from 1929 to 1933, stocks and other assets had to be sold to repay the debts incurred to purchase them, thus reversing the dynamics of the bubble into a crash. Naturally, the more borrowing and purchasing of stocks occurred, the better the stock performance, and the more people wanted to buy. These buyers could purchase stocks without selling anything because they could buy with credit. As the volume of credit purchases increased, credit tightened, and interest rates rose, both due to strong borrowing demand and because the Federal Reserve allowed interest rates to rise (i.e., tightened monetary policy). When borrowing needed to be repaid, stocks had to be sold to raise funds to repay the debt, leading to price declines, defaults on debts, reduced collateral values, decreased credit supply, and the bubble turned into a self-reinforcing crash, followed by an economic depression.

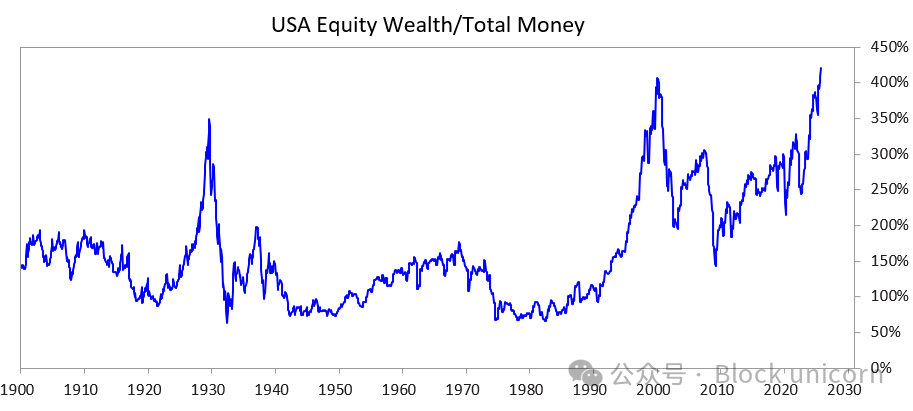

To explore how this dynamic, accompanied by significant wealth disparities, bursts bubbles and leads to a crash that can cause severe damage in social, political, and financial realms, I studied the chart below. This chart shows the wealth/money gap from the past and present, as well as the ratio of total stock market value to total money supply.

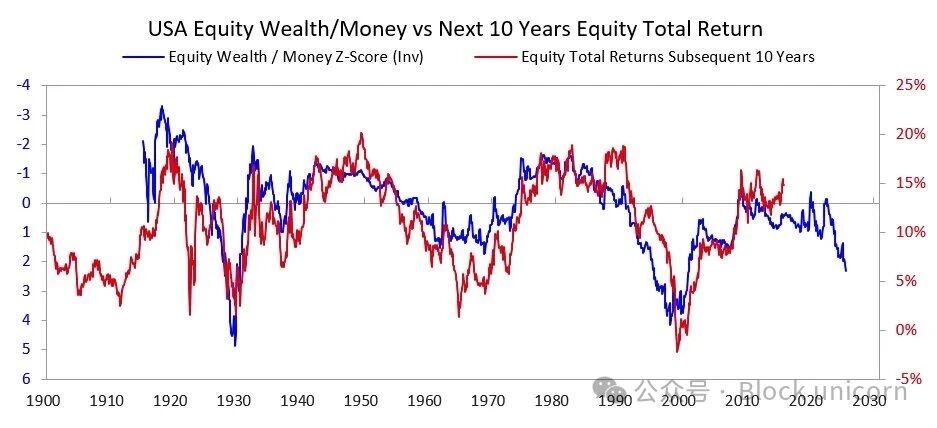

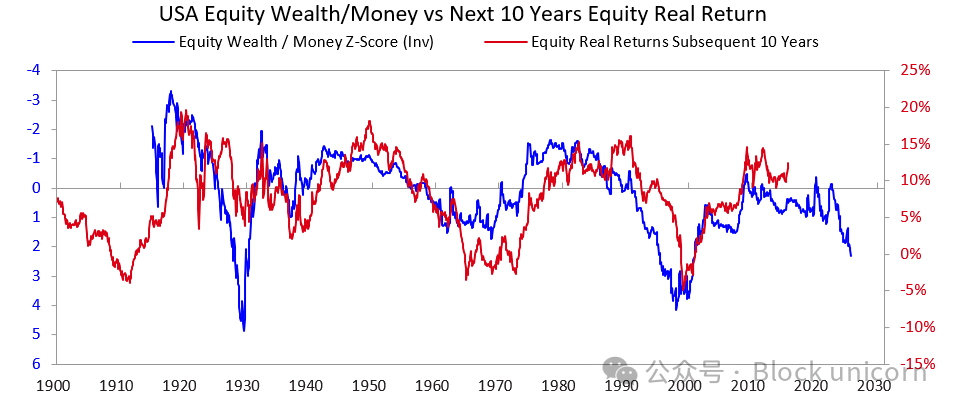

The next two charts illustrate how this indicator predicts nominal and real returns over the next 10 years. These charts speak for themselves.

When I hear someone trying to assess whether a stock or the stock market is in a bubble by judging whether a company can eventually earn enough to support its current stock price, I often feel that they fundamentally misunderstand the mechanics of bubbles. While long-term investment returns are indeed important, they are not the primary reason for a bubble's burst. A bubble does not burst because people suddenly wake up one morning and realize that a company's future income and profits are insufficient to support the current stock price. After all, whether sufficient income and profits can be generated to support a good investment return often takes many years, even decades, to determine. The principle we need to remember is:

A bubble bursts because the funds flowing into the assets begin to dry up, and holders of stocks or other wealth assets need to sell assets for money for some reason (most commonly to repay debts).

What usually happens next?

After a bubble bursts, when money and credit are insufficient to meet the needs of holders of financial assets, the market and economy will decline, and internal social and political unrest will typically intensify. This is particularly evident when there is a significant wealth gap, as it exacerbates the divide and anger between the rich/right and the poor/left. In the case we examined from 1927 to 1933, this dynamic triggered the Great Depression, leading to severe internal conflict, especially between the rich/right and the poor/left. This dynamic ultimately led to the ousting of President Hoover and the election of President Roosevelt.

Naturally, when a bubble bursts and the market and economy decline, it brings about significant political changes, large fiscal deficits, and massive debt monetization. Taking the case of 1927-1933 as an example, the market and economic decline occurred from 1929 to 1932, and political changes occurred in 1932, leading to a significant budget deficit for Roosevelt's government in 1933.

His central bank printed a large amount of money, leading to currency devaluation (for example, relative to gold). This method of currency devaluation alleviated the currency shortage and: a) helped systemically important debtors who were overwhelmed by debt to repay their debts; b) drove up asset prices; c) stimulated the economy. Leaders who come to power during such periods often implement many shocking fiscal reforms, which I cannot detail here, but I can assure you that these periods often lead to significant conflict and massive wealth transfers. In Roosevelt's case, these situations led to a series of major fiscal policy reforms aimed at transferring wealth from the top to the bottom (for example, raising the top marginal income tax rate from 25% in the 1920s to 79%, significantly increasing estate and gift taxes, and greatly expanding social welfare programs and subsidies). This also led to significant conflict within the nation and between nations.

This is the typical dynamic. Throughout history, this scenario has repeatedly occurred in countless countries over many years, forcing countless leaders and central banks to respond in the same way time and again, with too many cases to list here. By the way, before 1913, the United States had no central bank, and the government had no power to print money, making bank defaults and deflationary economic depressions more common. In either case, bondholders would suffer losses, while gold holders would profit significantly.

While the example of 1927-1933 illustrates the classic bubble-burst cycle well, that event was also relatively extreme. The same dynamics are reflected in the measures taken by President Nixon and the Federal Reserve in 1971, which nearly led to the occurrence of all other bubbles and crashes (for example, the Japanese financial crisis of 1989-1990, the internet bubble of 2000, etc.). These bubbles and crashes also exhibit many other typical characteristics (for example, markets are often driven by inexperienced investors who are attracted by the hype, leverage their purchases, incur massive losses, and then become furious).

This dynamic pattern has existed for thousands of years (i.e., when the demand for money exceeds supply). People have to sell wealth to obtain money, bubbles burst, followed by defaults, currency issuance, and adverse consequences in economic, social, and political realms. In other words, the imbalance between financial wealth and the amount of money, as well as the act of converting financial wealth (especially debt assets) into money, has always been the root cause of bank runs, whether in private banks or government-controlled central banks. These runs either lead to defaults (which mostly occurred before the establishment of the Federal Reserve) or prompt central banks to create money and credit to provide to those critical institutions that cannot fail, ensuring they can repay loans and avoid bankruptcy.

Therefore, please keep in mind:

When the scale of the promises to deliver currency (i.e., debt assets) far exceeds the total amount of existing funds, and there is a need to sell financial assets to obtain funds, one must be wary of a bubble burst and ensure personal protection (e.g., avoiding excessive credit risk and holding a certain amount of gold). If this situation occurs during a time of significant wealth disparity, it is essential to closely monitor potential major political and wealth redistribution changes and be prepared to respond.

While rising interest rates and credit tightening are the most common reasons for people to sell assets to obtain the necessary funds, any cause that creates a demand for funds (e.g., wealth taxes) and the act of selling financial wealth to obtain funds can lead to this dynamic.

When a massive wealth/money gap exists alongside a significant wealth disparity, it should be regarded as an extremely dangerous situation.

From the 1920s to Now

(If you do not wish to read a brief overview of how we have developed from the 1920s to the present, you may skip this section.)

While I previously mentioned how the bubble of the 1920s led to the crash of 1929-1933 and the Great Depression, for a quick recap, this bubble burst and the resulting Great Depression led President Roosevelt in 1933 to violate the U.S. government's promise to deliver hard currency (gold) at the promised price. The government printed a large amount of money, and the price of gold rose by about 70%. I will skip over how the reflation from 1933 to 1938 led to the tightening in 1938; how the "recession" of 1938-1939 created various factors needed for the economy and leadership, which, along with the geopolitical dynamics of Germany and Japan rising to challenge the two great powers of the U.S. and the U.K., ultimately led to World War II; and how the classic "long cycle" took us from 1939 to 1945 (the collapse of the old monetary, political, and geopolitical order and the establishment of a new order).

I will not delve into the reasons, but it is worth noting that these factors made the U.S. very wealthy (at that time, the U.S. held two-thirds of the world's money, all of which was gold) and powerful (the U.S. created half of the world's GDP and was the military hegemon at the time). Therefore, when the Bretton Woods system established a new monetary order, it was still based on gold, with the dollar pegged to gold (other countries could purchase gold at $35 per ounce with the dollars they obtained), and other countries' currencies were also pegged to gold. Then, from 1944 to 1971, U.S. government spending far exceeded tax revenues, leading to massive borrowing, and these debts were sold, creating gold claims that far exceeded the central bank's gold reserves. Seeing this situation, other countries began to exchange their paper currency for gold. This led to extreme tightening of money and credit, prompting President Nixon in 1971 to emulate President Roosevelt's actions in 1933, once again devaluing the currency relative to gold, causing gold prices to soar. In simple terms, from then until now, a) government debt and the cost of servicing that debt have risen sharply relative to the tax revenues needed to repay government debt (especially during the period from 2008 to 2012 following the global financial crisis and after the financial crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020); b) income and wealth disparities have expanded to the current level, causing irreconcilable political divisions; c) the stock market may be in a bubble, and the formation of that bubble is driven by speculation on new technologies supported by credit, debt, and innovation.

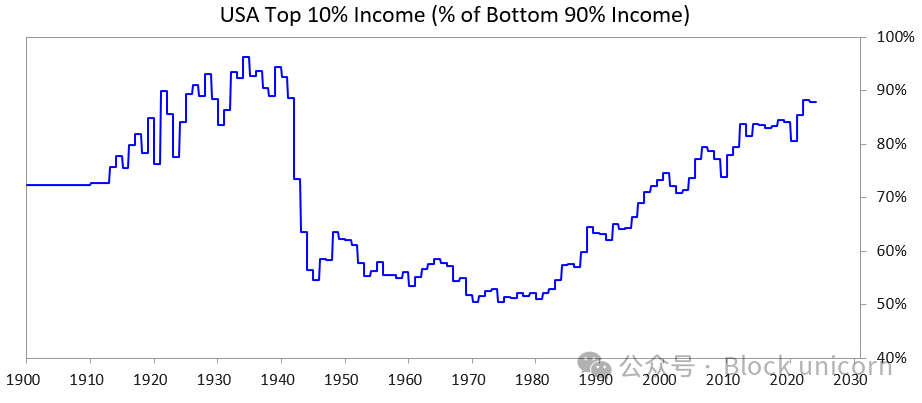

The chart below shows the income share of the top 10% of earners relative to the bottom 90%—you can see that the current gap is very large.

Where We Stand Now

The governments of the U.S. and all other over-indebted democracies now face a dilemma: a) they cannot increase debt as they once did; b) they cannot significantly raise taxes; c) they cannot drastically cut spending to avoid deficits and rising debt. They are now caught in a bind.

To explain in more detail:

They cannot borrow enough money because the free market's demand for their debt is insufficient. (This is because they are already heavily indebted, and their debt holders have too much debt.) Additionally, debt asset holders from other countries (e.g., China) are concerned that war conflicts may prevent them from recovering their debts, so they are reducing their bond purchases and shifting their debt assets to gold.

They cannot raise taxes because if they increase taxes on the wealthiest 1-10% (who hold most of the wealth), a) these individuals will leave, taking their tax dollars with them, or b) politicians will lose the support of the wealthiest 1-10% (which is crucial for funding expensive campaigns), or c) they will burst the bubble.

They also cannot significantly cut spending and welfare because this is politically, and even morally, unacceptable, especially since such cuts would disproportionately harm the bottom 60% of the population…

So they are trapped.

This is why all democracies with high debt, significant wealth disparities, and severe value divides are in trouble.

Given these circumstances, and the way democratic political systems operate along with human nature, politicians promise quick fixes but fail to deliver satisfactory results, quickly getting ousted in favor of new politicians who also promise quick solutions, only to be replaced again after failing—this cycle continues. This is why countries like the U.K. and France, which have systems for rapidly changing leaders, have replaced their prime ministers four times in the past five years.

In other words, we are now witnessing a classic pattern typical of this stage of the long cycle. This dynamic is extremely important and should now be evident.

Meanwhile, the stock market and wealth prosperity are highly concentrated in top AI-related stocks (e.g., the "Magnificent 7") and a few super-rich individuals, while AI is replacing humans, exacerbating the wealth/money gap and the wealth disparity between individuals. This dynamic has occurred multiple times in history, and I believe it is highly likely to trigger a strong political and social backlash, at the very least significantly altering the distribution of wealth, and in the worst-case scenario, leading to severe social and political unrest.

Now let’s examine how this dynamic and the massive wealth gap jointly create problems for monetary policy, and how wealth taxes can burst bubbles and trigger crashes.

What the Data Looks Like

Now I will compare the top 10% of wealth and income earners with the bottom 60% of wealth and income earners. I chose the bottom 60% because this group constitutes the vast majority.

In short:

The wealth, income, and stock holdings of the wealthiest individuals (top 1-10%) far exceed those of the majority (bottom 60%).

Most of the wealth of the richest comes from asset appreciation, which does not require taxation until the wealth is sold (unlike income, which is taxed upon receipt).

With the rapid development of AI, these gaps are widening and are likely to widen at an even faster pace.

If wealth is taxed, assets will need to be sold to pay the taxes, which could directly burst the bubble.

More specifically:

In the U.S., the top 10% of households are well-educated and highly productive economically, accounting for about 50% of income, owning about two-thirds of total wealth, holding about 90% of stocks, and paying about two-thirds of federal income taxes, with these numbers rapidly increasing. In other words, they live well and contribute significantly.

In contrast, the bottom 60% of the population is less educated (for example, 60% of Americans read below a sixth-grade level), relatively less productive economically, and their total income accounts for only about 30% of the national total, owning only 5% of total wealth, holding only about 5% of total stocks, and paying less than 5% of total federal taxes. Their wealth and economic prospects are relatively stagnant, making it economically difficult for them.

Naturally, there is immense pressure to tax wealth and money and redistribute wealth and money from the wealthiest 10% to the poorest 60%.

Although the U.S. has never had a wealth tax, there is now significant demand at both state and federal levels to implement one. Why was there no wealth tax before, and why is there one now? Because the money is concentrated there—meaning the top earners are primarily becoming wealthy through asset appreciation rather than labor income, and that appreciation is currently untaxed.

Wealth taxes have three major problems:

The wealthy can emigrate, and once they do, they take their talents, productivity, income, wealth, and tax capacity with them, reducing the place they leave and increasing the place they move to;

They are difficult to implement (you probably know the reasons; I won’t elaborate, as this article is already too long);

Taking funds used for investment and productivity enhancement and giving them to the government, hoping that the government can use them efficiently to make the bottom 60% productive and prosperous—this assumption is extremely unrealistic.

For these reasons, I prefer to impose an acceptable tax rate (e.g., 5-10%) on unrealized capital gains. But that is another topic for later discussion.

So How Would a Wealth Tax Work?

I will explore this issue more comprehensively in future articles. In short, U.S. household balance sheets show total wealth of about $150 trillion, but cash or deposits amount to less than $5 trillion. Therefore, if a 1-2% annual wealth tax were imposed, the required cash reserves would exceed $1-2 trillion annually—while the actual pool of liquid cash is far less than this.

Any similar action would burst the bubble and lead to an economic collapse. Of course, the wealth tax would not be imposed on everyone but only on the wealthy. This article is long enough, so I won’t go into specific numbers. In short, a wealth tax would: 1) trigger forced sell-offs of private equity and publicly traded equity, depressing valuations; 2) increase demand for credit, potentially raising borrowing costs for the wealthy and the market as a whole; 3) prompt wealth to flow or shift to more favorable jurisdictions. If the government imposes a wealth tax on unrealized gains or illiquid assets (e.g., private equity, venture capital, or even concentrated holdings of publicly traded equity), these pressures will become even more pronounced.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。